The Full Beaver Moon, Mostly Eclipsed, Harms Leo’s Meteors, and Algol Brightens!

This image of a total lunar eclipse by Michael Watson from October 8, 2014 somewhat resembles the appearance of the eclipsed moon on Friday morning, November 19, 2021. During that eclipse the moon passed near the northern (upper right) edge of Earth’s umbra. For this week’s eclipse, a bright slice of the moon will extend beyond the bottom of the Earth’s umbra. Michael’s terrific images can be enjoyed at his Flickr page at https://www.flickr.com/photos/97587627@N06/

Hello, November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 14th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a copy!

The moon will dominate the night sky worldwide this week as it waxes to full and a deep partial lunar eclipse on Friday morning. That bright moon will overwhelm the meteors from the Leonids shower. Three bright planets will shine in evening, the variable star Algol will brighten, on schedule, on Saturday, and Ceres will continue crossing Taurus’ face. Read on for your Skylights!

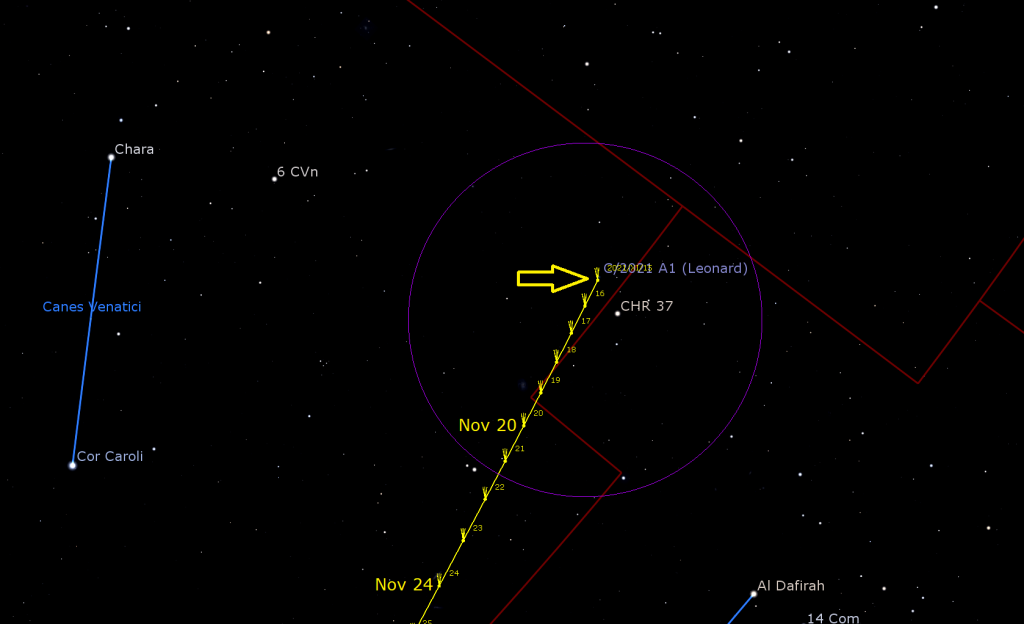

Comet Early Update

A comet named C/2021 A1 (Leonard) is predicted to brighten enough to see with unaided eyes during the first week of December, when it will appear in the eastern sky before sunrise. For now, the comet is within reach of telescopes once it rises after midnight among the stars of Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs).

The comet was discovered by G. J. Leonard at the Mount Lemmon Observatory on January 3, 2021, when the comet was 5 AU (or 750 million km) from the Sun. There is a recent photo of the comet here.

Leonids Meteor Shower

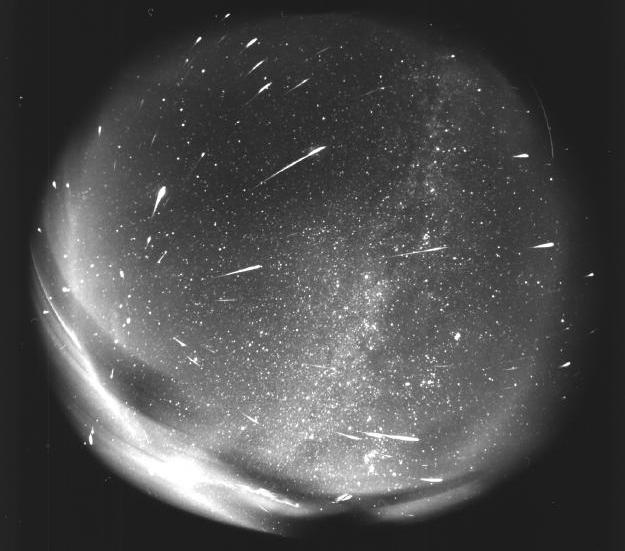

Over the next few months, the world will experience a procession of several fine meteor showers. The Leonids Meteor Shower, which is derived from bits of material dropped when periodic Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle traverses the inner solar system every 33 years, runs from November 5 to December 2, annually. The peak of the shower, when up to 15 meteors per hour are typical, will occur on Thursday morning in the Americas. At that time Earth will be traveling through the densest part of the comet’s debris field. The particles hit the atmosphere over our heads at such a high speed that they ionize the air through friction, producing the streaks of light you see as “shooting stars”. Many Leonids have persistent trains and strong colour.

This shower is a worldwide event. The meteors can appear anywhere in a dark sky, but true Leonids will be travelling in a direction away from a location called the radiant that is positioned among the stars that form the head of Leo (the Lion). (The radiant’s location gives each shower its name.) Don’t focus your attention on the radiant – the meteors near it will have very short streaks because they are traveling directly towards you.

The best viewing times for Leonids will be Thursday morning before dawn, when the radiant will be high in the eastern sky. You can watch for meteors on Wednesday evening, too – but many of them will be hidden from view below the Earth’s horizon. Unfortunately, a bright, full moon on the peak night will severely reduce the number of meteors we see. If you do venture out, find a safe, dark location with lots of open sky, get comfortable, and just look up.

To preserve your dark adaptation, try to keep your phone tucked away. If you must look at it, turn the screen brightness to minimum, and/or enabled the red screen mode available on some models. Don’t try to see meteors with binoculars or a telescope – those instruments have a field of view that is too narrow. But you can take long exposure photos of the sky and catch the meteors’ streaks. If the peak night is cloudy, don’t despair – the surrounding dates will still deliver some meteors. Happy viewing!

Watch Algol Brighten

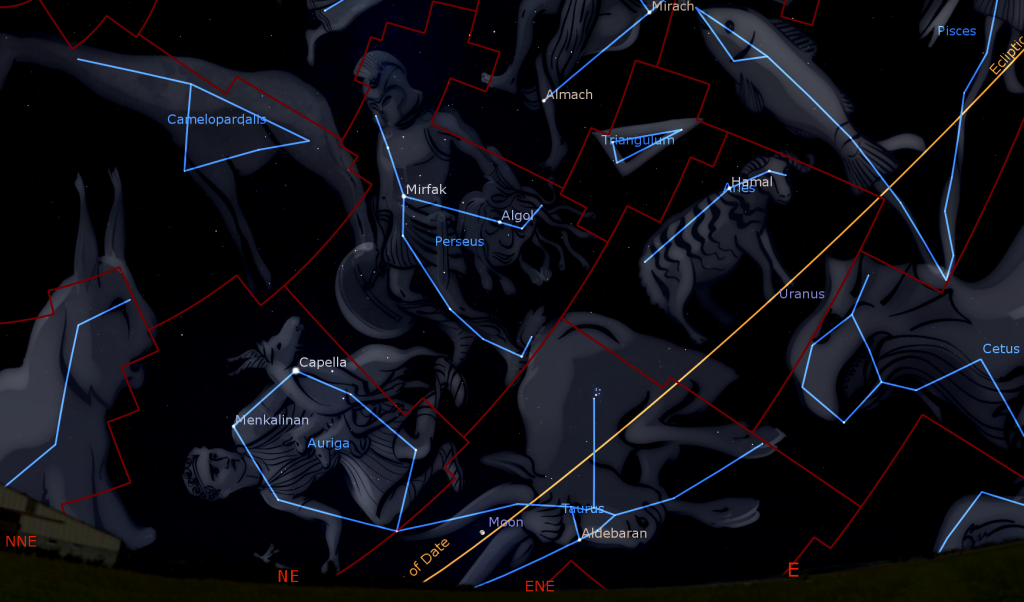

The star Algol, also designated Beta Persei and the Demon Star, is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. This star has been known to vary in brightness since antiquity – so the ancient Greeks decided that it represented the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head is being held aloft by Perseus (the Hero). During a ten-hour period that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol dims and re-brightens noticeably. This happens because a companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae). But while at minimum, Algol’s brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star sitting just two finger widths to the lower right (or 2.25 degrees south) of Algol. On Saturday, November 20 at 6:14 pm EST or 23:14 GMT, fully dimmed Algol will sit a third of the way up the east-northeastern sky. Five hours later the star will shine at full intensity from a perch overhead in the western sky.

The Moon

The moon will dominate the night sky this week – at least until after it passes its full phase on Friday morning. That full moon will come with an extra bonus – a partial lunar eclipse!

From tonight (Sunday) to Wednesday night, the waxing gibbous moon will swim along the crooked border between Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale). Those two constellations don’t have any bright stars, so the glare of the moon will all but hide them. The moon will be rising in late afternoon, so you can easily spot it sitting low in eastern sky before dinner. The moon will climb to a maximum height, more than halfway up the southern sky, at around 10 pm local time.

On Monday night, the pole-to-pole terminator that divides the lit and dark hemispheres of the waxing gibbous moon will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it with sharp eyes – and easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The “Golden Handle” is produced when slanted sunlight brightly illuminates the eastern side of the prominent, curved Montes Jura mountain range that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west), and by a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace to the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed under magnification at this phase.

On Thursday night, the 98.6% illuminated moon will enter Aries (the Ram) and will shine less than two finger widths below (or 2° to the celestial south of) the planet Uranus. Aries’ two bright stars Hamal and Sheratan will shine a fist’s diameter above Uranus. The Pleiades star cluster will be off to the left (celestial east). I recommend noting where Uranus is compared to those starry “landmarks” and return to it a few nights later, when the bright moon will be gone.

On Friday morning at 3:57 am EST or 08:57 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its full moon phase. Since it’s opposite the sun on that day of the lunar month, the full moon will rise around sunset on Thursday and set around sunrise on Friday morning. If you look closely at the moon on Thursday evening, you should be able to tell that it’s not quite full. A thin sliver on its upper right edge will still be dark – making it look less than perfectly round. When the moon rises at sunset on Friday evening, that darkened sliver will have jumped to moon’s opposite, left-hand edge – because the moon’s angle from the sun will have changed from 176 degrees east of the sun, to 173 degrees west of it. Friday morning’s full moon will also deliver a pre-dawn partial lunar eclipse. See below for the details.

The November Full Moon, traditionally known as the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Taurus and Aries. Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizis Oonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Rivers Freeze-up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenhko:wa, the “Time of Much Poverty Moon”.

On Friday night, the still very bright full moon will shine above the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull) and his bright, orange eye – the star Aldebaran. The moon will spend the rest of next weekend rising later and waning in phase as it traverses the bull’s stars. On Sunday night, November 21, the waning gibbous moon will be positioned several finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial west of) the large open star cluster named the Shoe-Buckle Cluster or Messier 35. The moon and the cluster will share the view in binoculars all night long, with the moon’s orbital motion halving their separation by dawn. To better see the cluster, which is nearly as wide as the moon itself, try hiding the moon just outside the top edge of your binoculars’ field of view.

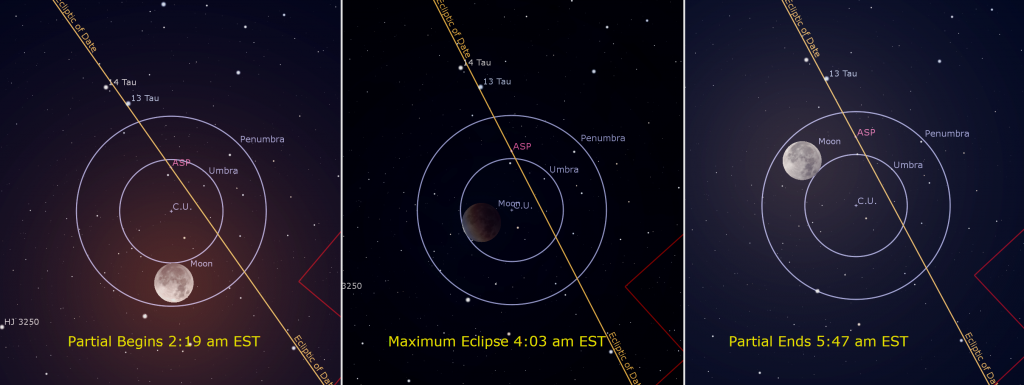

Friday Morning’s Partial Lunar Eclipse

Because the Earth is a solid sphere with sunlight shining upon it, it casts a circular shadow into space opposite from the sun, and close to the ecliptic. That black shadow is invisible against the black sky background. But if an object, such as the International Space Station or the moon, passes through that shadow, Earth’s solid bulk will prevent the sunlight from reaching the object, so the object darkens. If you watch satellites on a clear dark night, and note where in the sky they disappear (entering Earth’s shadow) or suddenly appear (exiting Earth’s shadow), you can trace out Earth’s shadow. It’s always there!

The zone where the sun is completely hidden by the Earth is called the umbra (that’s where the word “umbrella” – a sun shade – comes from). Surrounding this is a much larger circle called the penumbra, where some portion of the sun can still shine on an object. Objects passing through the penumbra will appear darkened, but still visible, from Earth.

The diameter of the shadowed region decreases as you move farther from Earth. At the moon’s distance, the umbra is about 1.25 degrees in diameter. The moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5 degrees compared to the ecliptic, so the moon can cross the ecliptic, and stray by up to about a palm’s width to the north and south of it. Lunar eclipses occur whenever a full moon phase occurs while the moon is close enough to the ecliptic for the moon to dip into Earth’s shadow. That happens 2 to 5 times per year.

If the moon completely enters the umbra, we see a total lunar eclipse. If part of the moon remains in the penumbra, we see a partial lunar eclipse. Either way, lunar eclipses are 100% safe to look at with unprotected eyes, both directly, and through binoculars – and to photograph. A telescope can even reveal the Earth’s shadow creeping across the moon’s surface in real time.

Earth’s atmosphere refracts (or bends) rays of sunlight because it slows the light down a little. Refraction allows sunlight to bend around the Earth’s horizon, letting some light reach even a fully eclipsed moon. It turns that moon reddish with sunset-coloured light, hence the nickname “blood moon” for eclipsed moons. If you could view the Earth from the surface of the moon during a total lunar eclipse, our dark globe would be encircled by a beautiful, narrow ring of reddish light!

Friday’s full moon will produce the second lunar eclipse of 2021! Unfortunately, this one will be happening during the wee hours. The moon will be too far enough south of the ecliptic for all of the moon to become eclipsed. A tiny sliver of the moon, about 2.5 % by area, will still receive sunlight during maximum eclipse – making this a deep partial lunar eclipse.

The moon slides steadily eastward in its orbit at a rate of about one lunar diameter per hour – so lunar eclipses are always rather slow events. This will be the longest partial lunar eclipse this century, in part because the moon will be less than 2 days from apogee, the moon’s maximum distance from the Earth. Kepler’s Laws of planetary motion demand that objects move slowest at apogee, so the moon will be taking longer to pass through Earth’s shadow.

At 1:02 am EST or 6:02 GMT, the moon will first touch the edge of the penumbra. As it sinks deeper into it, the moon will darken very slightly. The moon will first contact the umbra at 2:18:41 am EST or 7:18:41 GMT. That’s when you’ll begin to see the “bite” being taken out of the full moon – the beginning of the partial phase of the eclipse. The bite will cover more and more of the moon until maximum eclipse occurs at 4:02:56 am EST or 09:02:56 GMT.

Aside from the bright thin sliver of the moon’s southern rim sticking out of the shadow, the rest of the moon will darken to a ruddy red color – especially the moon’s northern half. The moon will then slowly leave the umbra, last touching it at the end of the partial phase at 5:47:04 am EST or 10:47:04 GMT – for a total eclipse duration of 3hours 28minutes. The slight darkening of the moon by the penumbra will continue until 7:04 am EST or 12:03 GMT.

A given lunar eclipse will be visible over about half the Earth’s globe. All of this eclipse will be visible from North America and nearly all of the Pacific Ocean. Eastern Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan will miss the early stages, while South America and western Europe will miss the final stages.

During maximum eclipse, objects around the bright full moon, such as the nearly Pleiades Star Cluster, will return to their full glory. You do not need to drive to a special site to see this eclipse, but you will want to ensure that the moon won’t be blocked by buildings or trees, especially if you plan to photograph the stages of the event. In the GTA, the moon will be 51 degrees above the west-southwestern horizon when the partial phase begins, 34 degrees above the western horizon at maximum eclipse, and only 15 degrees above the west-northwestern horizon at the end of the partial phase. The moon will be higher in the sky if you live farther west. Check the weather forecast before setting your alarm, and let me know if you see it!

The Virtual Telescope Project will start a livestream of the eclipse at 7:00 UT on Friday morning (2 am EST).

The Planets

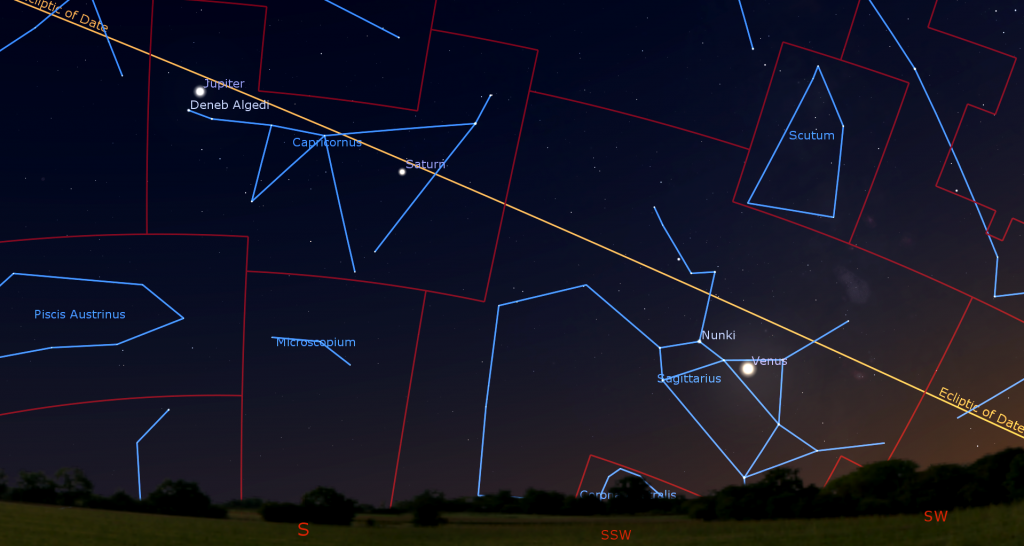

This week, brilliant Venus will shine low in the south-southwestern sky after sunset, and then set at about 7:30 pm local time. You might need to walk around to find a view of the planet between the trees or buildings after sunset. Viewed in a telescope, Venus will appear a bit less than half-illuminated, on its sun-facing side. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A light sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily. The planet will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year because Venus will be traveling into the space between Earth and the sun.

Jupiter and Saturn are huddled at the opposite ends of the constellation of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Jupiter’s bright, white dot will become visible, sitting less than a third of the way up the south-southeastern sky, a short time after dusk. 18 times fainter Saturn will appear, parked 1.5 fist diameters to Jupiter’s right (or 15.5° to the celestial west) once the sky darkens a bit more. They’ll reach their highest elevation in the sky, over the southern horizon, at around 5:45 pm local time – and then set in the west before midnight. Those two planets will get close to Venus during December.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from below (celestial south of) Saturn tonight to the upper right (celestial northwest) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk tonight (Sunday), Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday, and in mid-evening on Thursday and Saturday.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday night, November 15 Europa’s shadow will cross Jupiter from 7:05 pm to 10:45 pm EST. On Sunday night, November 21 Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 4:20 pm to 6:30 pm EST.

Uranus is still shining at its peak brightness of magnitude 5.65. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. It’s also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially after midnight, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky. The bright moon will pass close to it on Wednesday.

Distant, dim Neptune is in the sky all night long, too – near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes). The magnitude 7.85 planet is also 2.5 fist diameters to the left (or 27° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is not far away. This week, Pallas will be traveling slowly downward (or southward) through Aquarius, two finger widths above (celestial north of) the medium-bright star Tau Aquarii.

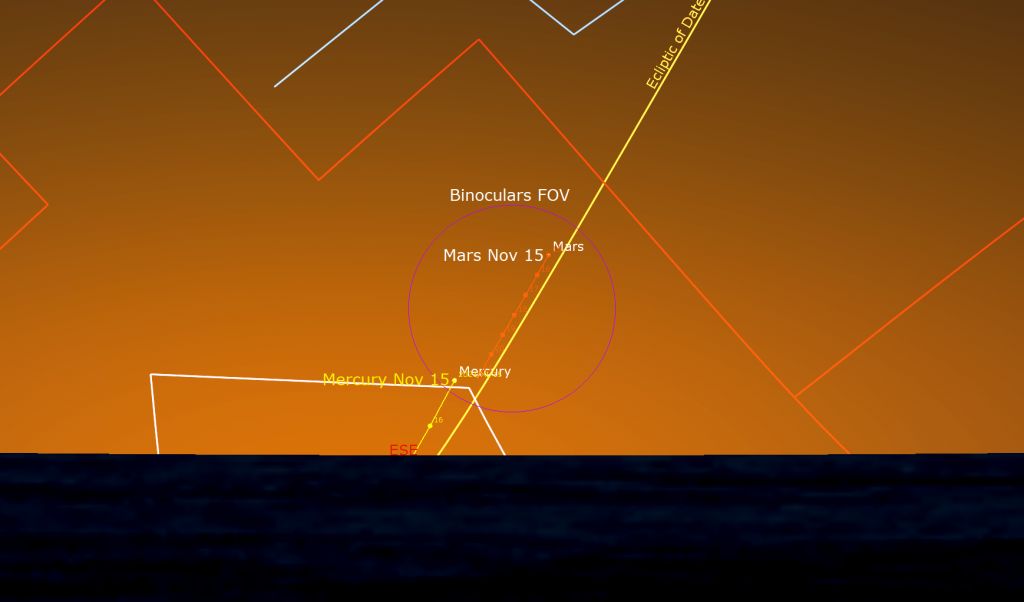

Mercury and Mars are still gathered in the eastern pre-dawn sky this week, but their close conjunction is over. Look just above the east-southeastern horizon before sunrise on Monday and Tuesday morning to see Mercury situated a few finger widths to the lower right (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial east) of Mars. You’ll need access to an unobstructed horizon and haze-free skies to see them. For this conjunction Mars will appear one-tenth as bright as magnitude -0.9 Mercury. In mid-northern latitudes, the best viewing time will be just before 7 am local time, when the two planets will sit a few degrees above the horizon, in a brightening sky. The duo will be close enough to appear together in the field of view of binoculars – but be sure to turn your optical aids away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises. Tropical latitude observers will see the two planets more easily – higher and in a darker sky.

Mercury will disappear into the sun’s glare from Wednesday on. Meanwhile, Mars will be increasing its angle from the sun – just beginning a year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022.

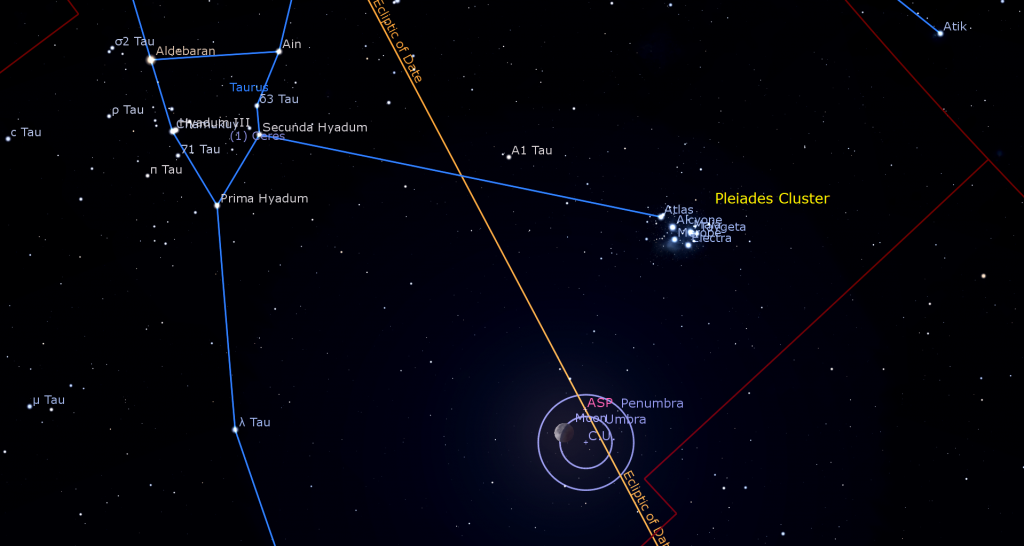

See Ceres

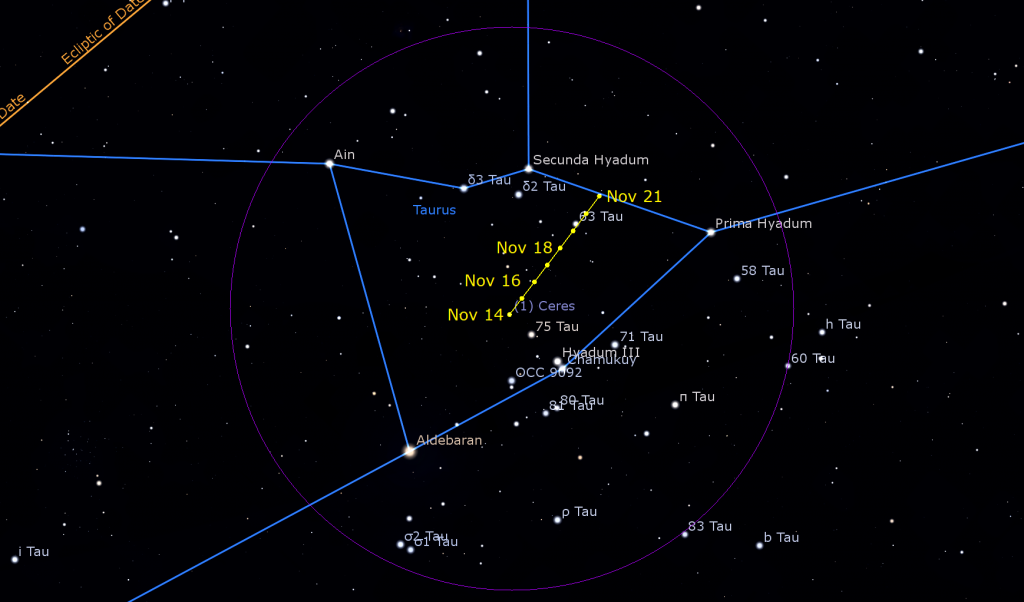

The orbital motion of the dwarf planet named (1) Ceres has been carrying it directly through the Hyades, the large open star cluster that forms the V-shaped face of Taurus (the Bull). Magnitude 7.6 Ceres is bright enough to see in a backyard telescope. Tonight (Sunday), Ceres, will be positioned in the centre of the triangle. For the rest of this week, Ceres will travel westward toward the upper (western) edge of the bull’s face.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Tuesday night, November 16 from 8 to 9 pm EDT, SkyNews Magazine editor Allendria Brunjes and Canadian astrophotographer Paul Owen will host Subs and Stars – Lesson 3 of a free, eight-part online series on astrophotography. This session will cover cleaning and fixing image flaws. Details are here, and the registration link is here.

On Wednesday evening, November 17 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature William Morin. His talk is titled The Geography That Guides Us: An Indigenous Perspective on our Relationship to the Stars. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Thursday, November 18 from 8:30 to 10:30 pm EST, Space Place Canada will stream From Canada to the Moon. Hours before a partial lunar eclipse host Kirsten Vanstone will discuss the moon with TEDx presenter Matthew Cimone. The session will stream live on YouTube. Details are here.

In-person sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but RASC are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead, in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Saturday night, November 20 from 7:30 to 9:00 pm EDT, the DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Dr. Roberto Abraham of the University of Toronto. He’ll speak on Cool stuff we discovered with Dragonfly, the many-lensed telescope. There will also be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday November 17, 2021 at 3 pm. Details are here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, November 23 when we’ll cover holiday gift ideas and astronomy accessories. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!