The Full Pink Moon Limits Lyrids and Spears Scorpius While Mars and Saturn Rise Early and Jupiter Exits Evening!

On April 10, 2024, my friend Alan Dyer captured this terrific image of the young moon (two days after the solar eclipse) shining above Uranus and Jupiter with moons. Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks is below them. The comet’s tail is aimed upwards away from the sun, which had recently set below the horizon. Follow Alan on FaceBook and on social media as AmazingSkyGuy.

Hello, Spring Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 21st, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Bruce, Grey and Simcoe Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

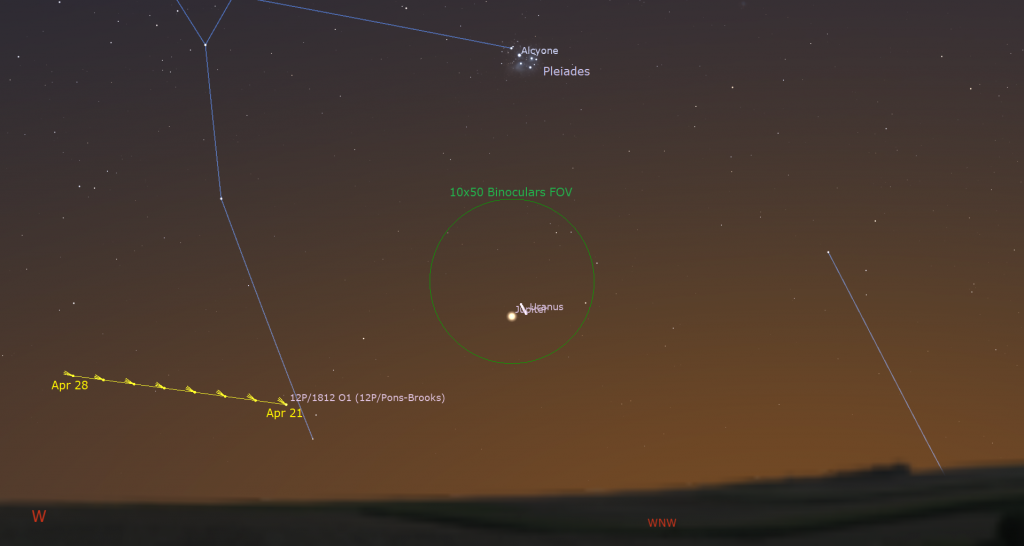

The moon will wax to full on Tuesday, which also connects to the timing of Passover. That moonlight will hamper this year’s Lyrids meteor shower, but it’s still worth a look for “shooting stars” from Sunday to Tuesday. In the west, Jupiter and nearby Uranus are setting earlier each evening, while comet 12P/Pons-Brooks scoots below them. The eastern pre-dawn hosts Saturn and Mars, which is sliding towards Neptune. Read on for your Skylights!

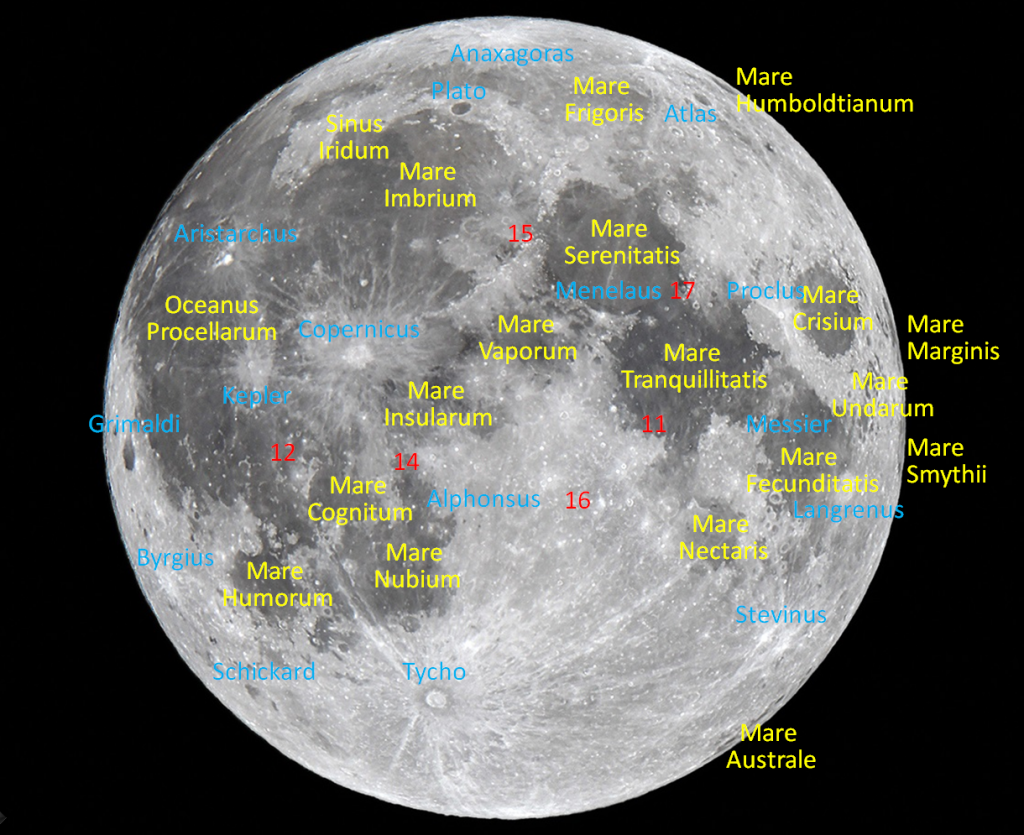

The Moon

The moon will brighten up the night sky worldwide this week – but it will be rising late enough on the coming weekend to offer some hours of moonless stargazing.

Tonight (Sunday) our nearly-full, natural nightlight will gleam above the eastern horizon at dusk and then cross the night all night long. The moon will spend Sunday through Tuesday crossing the lengthy constellation of Virgo (the Maiden). On Monday, the moon will be shining very close to Virgo’s brightest star Spica, which is 263 light-years away from our sun. The moon’s orbital motion will shift it closely above and then farther to the left of Spica. Early risers on Tuesday morning can look low in the southwest to see the moon positioned to Spica’s upper left (or celestial east-southeast).

The moon will officially reach its full phase at 7:49 pm EDT or 4:49 pm PDT or 23:49 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, April 23. April’s full moon always shines in or near the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) or Libra (the Scales). Full moons are, by definition, opposite to the sun in the sky, so they always rise in the east as the sun sets, and set in the west at sunrise – but lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation.

Every culture around the world has developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more names. The indigenous Ojibwe groups of the Great Lakes region call the April full moon Iskigamizige-giizis “Maple Sap Boiling Moon” or Namebine-giizis, the “Sucker Moon”. For them it signifies a time to learn cleansing and healing ways. The Cree of North America call it Niskipisim, the “the Goose Moon” – the time when the geese return with spring. For the Mi’kmaw people of Eastern Canada, this is Penatmuiku’s, the Birds Laying Eggs Time moon. The Cherokee call it Kawonuhi, the “the Flower Moon”, when the plants bloom. For Europeans, it is commonly called the Pink Moon, Sprouting Grass Moon, Egg Moon, or Fish Moon. All of these terms reflect the changes in the natural environment at this time of year. It seems that “pink” refers to the phlox flowers that bloom first during spring in eastern forests – and NOT to the way the moon will appear!

Greetings to those who observe Passover! Easter Sunday and Pesach (Passover) have an astronomical connection to the full moon, with the Jewish Passover pre-dating the Christian Easter. Some believe that a full moon allowed for safer travelling by religious pilgrims of the time.

In 325 CE the Council of Nicaea determined that the moveable feast of Easter should be observed on the Sunday following the first full moon that occurs after the vernal equinox, officially known as the Paschal Full Moon. The council fixed the equinox at March 21, but the astronomical timing of the equinox actually varies a little bit, and even occurs a full day early on leap years. This year, the equinox occurred on March 19, so Easter was observed on Sunday, March 31. The name “paschal” is derived from “Pascha”, a transliteration of the Aramaic word meaning Passover.

The Paschal moon controls the timing of Easter and Passover in different ways – which is why they are sometimes a month apart. Passover or Pesach is celebrated from the 15th through the 22nd of the Hebrew month of Nissan in the Jewish lunar calendar. Nissan began on April 9, when the new moon could first be spotted in Israel, so Passover will commence at sundown on Monday, April 22 and end at nightfall on Tuesday, April 30. Lunar calendars drift from solar calendars because there are 12.3 lunar months in a 365.25 day solar year. To correct for that, an intercalary or leap-month is inserted about every three years. In years when the post-equinox full moon occurs early, as it was in 2024, Jewish religious leaders delay Passover by inserting a second month of Adar, called Adar II, to ensure that spring-like weather conditions (warmer temperatures and flowers in bloom) have arrived in Israel. The earliest that Passover can occur in our Gregorian calendar is March 25, which will next happen in 2089.

After Tuesday, the moon will rise about 70 minutes later each night and wane in phase. On Wednesday, it will visit Libra (the Scales). Once the bright, waning gibbous moon clears the treetops in the east around midnight local time on Thursday, it will be shining among the little white claw stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion) and almost a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or celestial west-northwest) of the very bright reddish star Antares, which marks the scorpion’s heart. By dawn on Friday morning in the Americas, the moon will have crept a bit closer to Antares. Almost a day later, skywatchers from northeastern Africa and parts of the Middle East and across the Indian Ocean to Indonesia can see the orbital motion of the moon carry it in front of (or occult) Antares in the wee hours of April 27.

From Friday on, you’ll need to stay up beyond midnight to see the moon – or look low in the south and west as the sky brightens around breakfast time. If you get outside before dawn next Sunday, you can see the waning gibbous moon shining to the right of the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

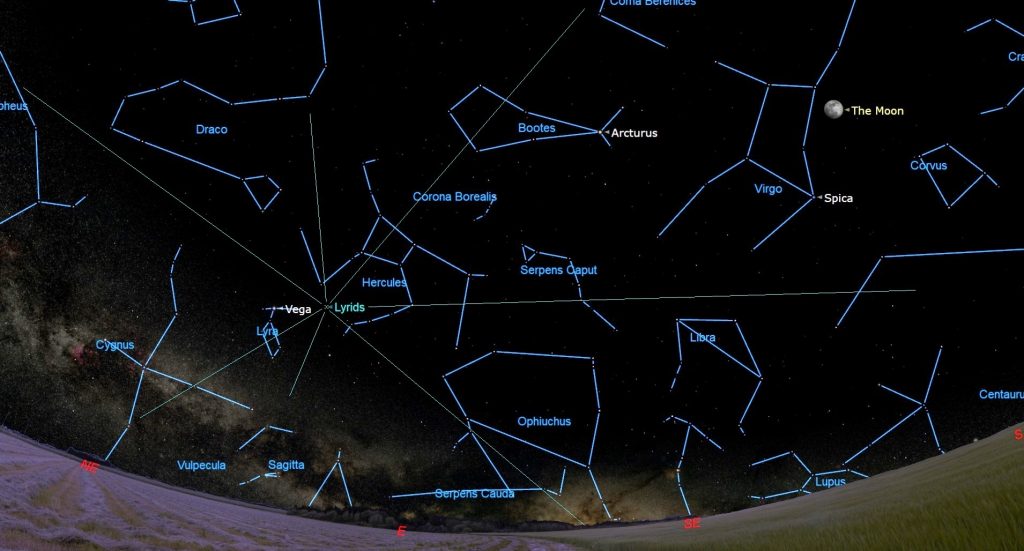

Lyrids Meteor Shower

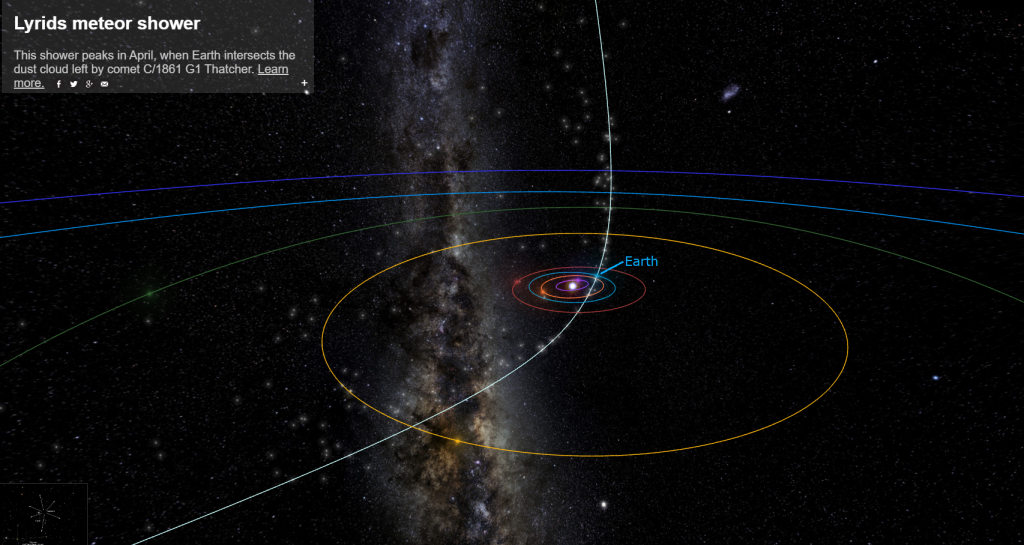

The annual Lyrids Meteor Shower will peak in intensity at approximately 3 am EDT on Monday, April 22, but you can look for meteors as the sky darkens tonight (Sunday evening). Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through zones of debris shed by repeated passages of periodic comets with orbits that intersect Earth’s. (An analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over centuries and millennia, the dust-sized and sand-sized particles accumulate in a zone that surrounds the comet’s orbit, with their distributions densest along the orbit and tapering off in the zone around it.

While the Earth plows through one of those clouds of cometary debris, the particles are pulled in by our gravity and zip through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The grains moving that fast through the air generate intense heat that ionizes the air in a long, narrow tube surrounding the particle’s track – producing the long, glowing trails we see as meteors.

The duration of a particular meteor shower depends on the width of the debris cloud and whether the Earth moves across it perpendicularly, or performs a longer, oblique crossing. The shower’s intensity depends on whether we pass through the densest region, or merely skirt its edges. Since the Earth passes through the same part of the solar system on the same date every year, meteor showers repeat annually. Fluctuations in the geometry of the encounter can cause showers to vary from their predicted behavior – and even produce unexpected outbursts in some years.

The source particles for the Lyrids shower is thought to be a comet named C/1861 G1 (Thatcher), after its discoverer A. E. Thatcher. It orbits the sun every 416 years, shuttling between the distant Kuiper Belt (110 times farther from the sun than we are) and just inside Earth’s orbit. Comet Thatcher’s orbit is at right angles to the planets’ orbits. It is expected to dive across the plane of the inner solar system next around the year 2283. You can manipulate a 3D model of the orbits here. According to NASA, the Lyrids were documented by Chinese astronomers in 687 BCE – making this one of the oldest recorded meteor showers.

Meteor showers ramp up and then taper off during their active periods. For the Lyrids shower that’s April 16 through April 29. Expect up to 10-20 Lyrids meteors per hour at the peak – some manifesting as bright, sputtering fireballs! Unfortunately, a bright, full moon will spoil the shower this year.

Usually, meteor showers are best observed in the dark skies before dawn, because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splattering on a moving car’s windshield. The direction in the sky that is Earth is travelling towards (or the road ahead, to use my car analogy) is called the radiant. All the meteors from a particular shower’s source will seem to be travelling away from, or radiating, from that location. The constellation containing the radiant gives the shower its name. Long ago, the Lyrids radiant was located in the constellation of Lyra (the Harp), near the bright star Vega. Over time, the slow wobble of Earth’s axis has shifted the radiant into next-door Hercules.

Right after dusk on Sunday evening, you might catch a few spectacular, very long meteors that are skimming the Earth’s upper atmosphere. As the night rolls on, the radiant will rise higher in the sky, revealing more meteors because they will no longer be hidden by the bulk of the Earth. Normally, the absolute best time to watch is when the radiant is almost overhead, between 4 and 5 am in your local time zone.

For best results, try to find a dark, safe viewing location with as much open sky as possible. You can start watching as soon as it gets dark. Don’t bother watching the radiant. Meteors near there will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. But do try tracing the meteors backwards to their source. If you can, hide the bright moon behind a building or tree and just look up.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to continuously watch the sky, even when chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun! You’ll also see plenty of satellites gliding silently and smoothly across the sky. (Airplanes have lights that flash while satellites emit a steady, or sometimes slowly pulsing, glint of reflected sunlight.)

Keep your phone or tablet tucked away – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you can’t resist some screen time, minimize the brightness and/or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors because they have fields of view that are too narrow. Good luck!

By the way, the nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”. But meteors bear no physical connection to the distant stars at all. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

The Planets

Jupiter’s brightness is allowing us to find it shining above the western horizon after sunset this week – but the task will get harder as the planet shifts closer to the sun and lower in the sky each day. Jupiter will set around 9:45 pm local time this week, but the later sunsets will be working against us. Periodic comet 12P/Pons-Brooks will be located a fist’s diameter to the lower left of Jupiter this week and the distant and faint planet Uranus will also be descending just to Jupiter’s right – but the twilit sky will hide them. You can still enjoy the pretty little Pleiades cluster of stars sparkling above Jupiter.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another.

The medium-bright duo of Mars and Saturn will rise around 5 am local time and clear the rooftops in the east-southeast about half an hour later. The two planets will shine with almost the same intensity until the brightening sky hides them. Reddish Mars will be located more than a palm’s width to the lower left of yellowish Saturn, but its faster orbital motion will nearly boost its separation from Saturn this week.

Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises. The severely tilted morning ecliptic will keep the planets low in a brightening sky, but observers living closer to the tropics, where the ecliptic will stand upright, will have a much easier view of them. Mars will also be travelling directly towards Neptune. By next Sunday morning, Neptune will be positioned only a pinky finger’s width to Mars’ lower left (or 0.6 ° to the celestial ENE). They’ll already be close enough to share the view in a telescope on Saturday.

The inner planets Mercury and Venus are rising shortly before the sun every morning, making them a challenge to see unless you live near the equator. Venus will meet the sun at solar conjunction in early June.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, April 28 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sun Fun. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 6 and up and runs rain or shine, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!