The New Moon brings Delightfully Dark Nights – Perfect for Looking at Lyra’s Lights!

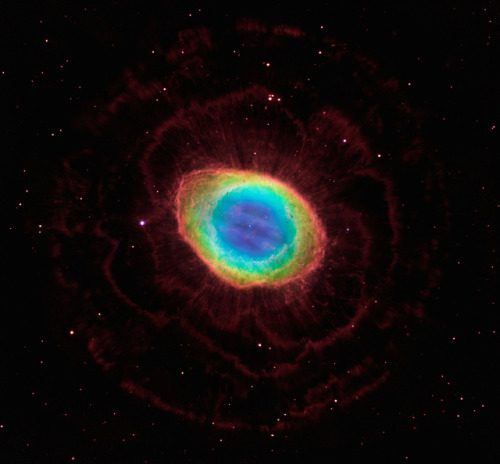

This image of the Ring Nebula in Lyra was produced by combining images from the Hubble Space Telescope with infrared data from the ground-based Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona. In the image, the blue color represents helium; the green, oxygen; and the red, hydrogen. hubblesite.org

Hello, Late Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 25th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeoguy.tumblr.com/ where all the old editions are archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. Please click this MailChimp link to subscribe to these emails.

I can bring my Digital Starlab inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The Moon and Planets

This is the favorite week of the lunar month for skywatchers worldwide. The nights between Last Quarter and the New Moon are delightfully dark, and the mild temperatures will entice you outside to see the sights. Here are your Skylights!

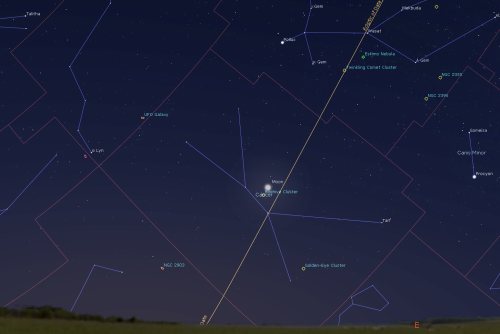

The moon will begin the week as a pretty waning crescent that rises in the wee hours among the stars of Gemini (the Twins). That late-rising moon will remain visible during the daylight hours – well into the afternoon, in fact. Low in the east-northeastern sky, just before dawn on Wednesday morning, the delicate crescent of the old moon will land on the outskirts of the large open star cluster known as the Beehive and Messier 44 in Cancer (the Crab). The best viewing time will occur between about 4:30 and 5:30 am local time. If you place the moon in your binoculars, the cluster’s stars will be sprinkled below the moon (or above it, if you live south of the equator).

(Above: Two views of the old crescent moon’s encounter with the Beehive open star cluster aka Messier 44 in Cancer on Wednesday morning, shown here at 5:30 am local time.)

You can look for the very slim moon sitting low in the eastern sky before sunrise on Thursday morning. On Friday morning at 6:37 am EDT, the moon will reach its new moon phase. When new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight is only reaching the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon will be completely hidden from view – from Earth.

The moon’s 27.32-day orbit around Earth is not circular, but elliptical – causing the moon to vary in distance by up to 6% (closer and farther) from the average Earth-moon distance of 385,000 lm. (That variation is responsible for producing occasional “supermoons”.) Because the moon’s closest approach to Earth (perigee) will occur only 5.5 hours after the moon’s new phase, the combined gravitational tugs of the sun and moon pulling from the same direction in space will generate large tides on Earth for several days.

The moon moves across the sky at a pretty high rate of speed – shifting by its diameter every hour. The fresh, young crescent moon will re-appear, low in the western evening sky after sunset, on Saturday evening. If you miss it, try again on Sunday, when the higher and thicker crescent will sit a fist’s diameter to the right (celestial northwest) of the bright star Spica in Virgo (the Maiden) before setting at about 9:30 pm local time.

(Above: On Sunday evening, September 1, the pretty, young crescent moon will appear low in the western post-sunset sky, to the right of the bright star Spica, as shown here at 8:35 pm EDT.)

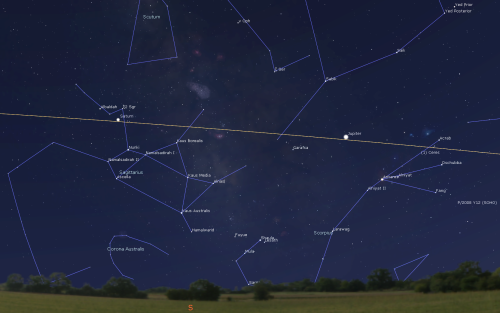

Jupiter will continue to be the brightest object in the evening sky this week. As the sky begins to darken, look for the giant planet sitting less than a third of the way up the southern sky. Hour by hour, Jupiter will sink lower – then set in the west just after midnight local time. Jupiter is spending this summer above Scorpius (the Scorpion), in the southern part of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). I described Ophiuchus, which resembles a huge Dalek from Doctor Who, here.

On a typical night, even a backyard telescope will show you Jupiter’s two main equatorial stripes and its four Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede looking like small white dots arranged in a rough line flanking the planet. If you see fewer than four dots, then some of them are in front of Jupiter, or hidden behind it. Good binoculars will show the moons, too!

(Above: The bright planets Jupiter and Saturn will continue to dominate the evening sky this week, as shown here at 9 pm local time. The distinctive Teapot and Scorpion are below the planets.)

Over the next few nights, Jupiter will be passing very close to a dim, fuzzy patch of stars – a globular star cluster named NGC 6235 (from the New General Catalogue of deep sky objects). This collection of several hundred thousand stars, arranged by their mutual gravity into a densely packed sphere, is one of many such objects known to orbit our Milky Way galaxy. It is located 38,000 light years away from our solar system! When you see it, you are looking into the distant past. The light from those stars began traveling towards us around the time that Neanderthals died out! Jupiter is overwhelmingly bright compared to the cluster, so try hiding Jupiter just beyond your optics’ field of view. Remember that most telescopes will flip the view around – so check both to the left and right of the planet.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter’s surface by those four Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) Jupiter’s disk. On Wednesday night from dusk to 9:30 pm EDT, observers in the Americas can watch Io’s small shadow transit Jupiter – with the Great Red Spot! On Thursday night from dusk to 9:40 pm EDT, observers in the Americas can watch Ganymede’s shadow transit the northern hemisphere of Jupiter.

Due to Jupiter’s rapid 10-hour rotation period, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) is only observable from Earth every 2nd or 3rd night, and only during a predictable three-hour window. The GRS will be easiest to see using a medium-sized, or larger, aperture telescope on an evening of good seeing (steady air). If you’d like to see the Great Red Spot in your telescope, it will be crossing the planet on Monday evening from dusk to 10 pm EDT, on Wednesday night from 8:40 pm (in twilight) until 11:45 pm EDT, on Friday from 10:20 pm until Jupiter sets, and on Saturday after dusk.

Yellow-tinted Saturn is prominent in the southern evening sky, too – but it is less bright than Jupiter. The ringed planet will be visible from dusk until almost 2:30 am local time. Saturn’s position in the sky is just to the upper left (or celestial east) of the stars that form the teapot-shaped constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer). To find Saturn, look about 3 fist diameters to the left (east) of Jupiter. The Milky Way is between them.

Dust off your telescope! Once the sky is dark, even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons, especially Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the upper left of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will flip the view around.)

Tiny, blue Neptune will rise at dusk this week, and then it will climb the eastern sky until it reaches its highest point, due south, at about 2:20 am local time. The planet is among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), sitting less than half a finger’s width to the left (celestial east) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. Both objects will appear together in the field of view of a telescope. Neptune is actually moving slowly toward that star and will “kiss” it in early September.

(Above: The ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune will soon become evening targets. this view shows them at 11 pm local time.The asteroid labeled (15) Eunomia at upper right is a little bit dimmer than Neptune, but within reach of backyard telescopes.)

Blue-green Uranus will be rising in the east at about 10:30 pm local time this week; and it will remain visible all night long. Uranus is sitting below (celestial south of) the stars of Aries (the Ram) and is just a palm’s width above the head of Cetus (the Whale). At magnitude 5.8, Uranus is actually bright enough to see in binoculars and small telescopes, under dark skies – and it really does look blue! You can use the three modest stars that form the top of the head of the whale (or sea-monster in some tales) to locate Uranus for months to come – that’s because that distant planet moves so slowly in its orbit. To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here.

Bright and speedy little Mercury is very low in the east-northeastern pre-dawn sky – but it is descending sunward. Your best opportunity to see it comes early in the week in the minutes surrounding 6 am local time. Venus and Mars are out of action for now. They are snuggling up together in the sun’s glare.

August-September Stargazing Suggestions – Lyra

With the Moon out of the evening sky this week and evening darkness arriving a bit earlier, it’s a good time to tour the night sky.

(Above:The region around the zenith on late August and early September evenings, features the Summer Triangle and the constellations Lyra, the Harp, Cygnus, the Swan, and Aquila, the Eagle. The sky is shown for 10 pm local time.)

Once it’s dark, tilt your head back and look waaay up. Or set out a blanket, gravity chair, or chaise. Point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith – the point of the sky directly above you. During the night, various stars and constellations will pass through that patch of sky as the Earth’s rotation carries them from east to west. While objects occupy that position, they will always appear at their best. That’s because you are looking through the thinnest blanket of intervening air. (Light from objects near the horizon has to pass through as much as ten times more turbulent air – making the objects a blurry mess!)

In early evening in early September every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), Hercules, and Draco (the Dragon) occupy the zenith. Over the next weeks, we’ll tour them, pointing out some objects you can look at with binoculars and small telescopes. Up first is Lyra. In Greek mythology, Lyra was the musical instrument created from a turtle shell by Hermes and later used by Orpheus in his ill-fated attempt to rescue his lost love Eurydice from the underworld. We Canadian astronomers call Lyra the “Tim Hortons Constellation” because it contains both a doughnut and a double-double coffee!

Facing south and looking just to the lower right of the zenith, you’ll easily spot the very bright star Vega, also known as Alpha Lyrae – the brightest star in the constellation. Vega, the fifth brightest star in the entire night sky – partly because it is only about 25 light years away from us, and partly because it is a very hot, luminous star. The name Vega arises from the Arabic “Al Nasr al Waqi”, or the “swooping eagle”. Traditionally, the Lyre was pictured as being grasped in the talons of an eagle.

Vega is moving towards the Sun and will continually brighten over time, becoming the brightest star in the night sky a few hundred thousand years from now. Meanwhile, the wobble of the Earth’s axis will also cause Vega to displace Polaris as the northern Pole Star. That will happen around 14,500 AD. It was previously the pole star around 12,000 BC. This star is a star!

Vega is also the brightest, highest, and most westerly of the three beautiful, blue-white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism. Moving clockwise, Altair is about three fist widths below and to the left of Vega. Deneb, slightly dimmer than the other two, completes the large triangle at the upper left. The separation between Deneb and Vega is shorter, only 24°, or 2.5 fist widths.

Chinese culture celebrates a love story in which a Cowherd named Niú Láng (牛郎) is the star Altair. Long ago the Cowherd and his two children, (β and γ Aquilae, the stars that flank Altair) were separated from their mother Zhī Nǚ (織女) the “Weaving Girl” (Vega). She is now on the far side of the river, which is represented by the Milky Way. As the story goes, each year, on the seventh day of the seventh month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, magpies make a bridge across the Milky Way – so that the family can be together again for a single night. Some astronomers believe that the magpies are actually Perseid meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

(Above: A close-up view of Lyra)

Look for a medium-dim star about a finger’s width to the left of Vega. A similarly dim star sits about a finger’s width below it. The three stars form a neat little triangle with Vega on the right. Binoculars or a small telescope will reveal that the triangle’s star to the left of Vega, designated Epsilon Lyrae, is actually a close pair of stars. A really good telescope will reveal that each of the pair of stars is itself a very close together pair! This quadruple star system, or “double-double”, is about 162 light-years from Earth. Even more interesting, each little pair is circling one another, and the two pairs may also be orbiting – in a neat little square dance that takes thousands of years to complete! And that’s your Tim Hortons coffee!

The other corner of our little triangle is the star Zeta Lyrae, and it, too can be split into a double star with binoculars. Both are white and one is slightly brighter than its partner. These stars are about 152 light-years away, and they themselves have partners that are too close together to split visually.

Zeta is also the top right star of a narrow, upright parallelogram about two fingers wide and four fingers tall that forms the rest of the constellation. Moving clockwise, we find Sheliak, Sulafat, and Delta Lyrae. Sheliak, meaning “Harp”, is the brightest of a tight little grouping of stars visible in a telescope. Sheliak itself has a close-in, dim partner that orbits the main star so that, every 13 days, the brighter star is blocked and the total brightness drops by a noticeable amount. This is called an Eclipsing Binary system.

Next, at the bottom of the parallelogram, sits Sulafat, meaning “Turtle”, and named for the shell forming the body of the Lyre. Sulafat is a hot, blue giant star located 620 light-years away. Similar in colour to Vega, Sulafat is much larger – an old star on its way to becoming an orange giant many years from now.

Finally, at the upper left of the parallelogram is Delta Lyrae. Sharp eyes and binoculars will easily reveal that this is yet another pair of stars – one blue (upper) and one red (lower). The two are not related – the blue star is several hundred light-years farther away than the red one. They just happen to appear close together along the same line of sight.

(Above: The famous Double-Double, also known as Epsilon Lyrae sits a finger’s width from the very bright star Vega in Lyra. This view simulates what a telescope will show.)

So, where’s our doughnut? Train your telescope midway between Sheliak and Sulafat, and look for the little, dim, grey smoke ring known as the Ring Nebula (also known as Messier 57). This little bubble of gas in space is the remnant of a dead star of a similar mass to our Sun. These common objects are called planetary nebulae because they exhibit a little round disk, like a planet. Finally, using binoculars or a telescope, sweep to the lower left the line that joins Sheliak to Sulafat. At about twice their separation (from Sulafat) is a Globular Star Cluster called Messier 56. It will appear as a dim fuzzy patch – a Timbit!

Let me know how your exploration of Lyra goes. There are lots of double stars in the constellation.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Taking advantage of dark, moonless evening skies this week, astronomers with the RASC Toronto Centre will gather for dark sky stargazing at Long Sault Conservation Area, northeast of Oshawa on (only) the first clear evening (Monday to Thursday) this week. You don’t need to be a RASC member, or own any equipment, to join them. Check here for details and watch the banner on their homepage or their Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes. If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Details are here.

On Tuesday, August 20, starting at 7 pm, U of T’s AstroTour planetarium show will be Grand Tour of the Cosmos. Find tickets and details here.

If the skies are clear on Thursday evening, September 5, local astronomers will set up their telescopes in Old Thornhill Village. This free event starts at 8 pm and everyone is welcome to come out for a look at the Moon, Jupiter and Saturn, and a variety of deep-sky treasures. The viewing location is Thornhill’s very own “dark-sky oasis,” the Pomona Meadow – situated north of the cemetery on Charles Lane, and east of the Ukrainian Catholic Church of St. Volodymyr. Park for free at the church and just follow the paved path. The rain or cloud date is Thursday, October 3 at 7:00pm. Dress warmly, and we’ll see you there!

On Wednesday, August 28 at 6 pm at U of T’s Bahen Centre for Information Technology, 40 St George St, the Iranian Association at University of Toronto (IAUT) will present A Thousand Nights Under Stars – a lecture by science journalist and NatGeo photographer Babak Tafreshi. To register for this free event, click here.

The next RASC-hosted Night at the David Dunlap Observatory will be on Saturday, September 14. There will be sky tours in the Skylab planetarium room, space crafts, a tour of the giant 74” telescope, and viewing through the 74” and lawn telescopes (weather permitting). The doors will open at 8:30 pm for a 9 pm start. Attendance is by tickets only, available here. If you are a RASC Toronto Centre member and wish to help us at DDO in the future, please fill out the volunteer form here. And to join RASC Toronto Centre, visit this page.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!