The New Moon Drives Diwali, Lots of Leonids Meteors, Plentiful Planets, and Copious Comets!

My friend Lisa Ann Fanning of New Jersey captured the spectacular morning conjunction of the crescent moon and Venus from the Cape May Lighthouse on November 10, 2023.

Hello, November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 12th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The Festival of Lights, Diwali, will mark this month’s new moon. While the moon slowly returns to shine in the evening sky, you can use the moonless nights to watch for Leonids meteors and several comets that are within reach of everyday stargazers. The four big planets continue to dominate the evening and late-night sky, while Venus will gleam in the east until sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy Diwali!

Like many traditional observances around the world, the timing of the South Asian festival of Diwali, or the Festival of Lights, has an astronomical connection. It lasts five days, always beginning just before the new moon phase that falls between mid-October and mid-November – dubbed “the darkest night of the year”. In 2023, Diwali will commence on Sunday evening, November 12, just hours before Monday morning’s new moon. Expect to hear some fireworks, or to see some colourful lights from celebrants!

Diwali celebrates the triumph of good over evil after the fall harvest. The festival’s name arises from the Sanskrit expression deepa avali, or “rows of lighted clay lamps” – which were set outside when there was no moon to light the way at night.

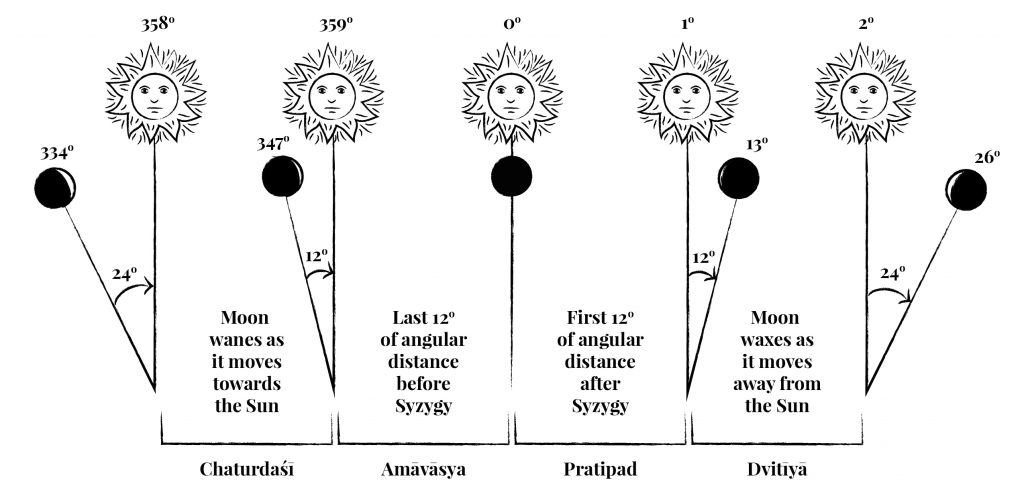

The Hindu lunisolar calendar employs twelve 30-day months within a 360-day year. To avoid calendar drift caused by its annual five day shortfall, it adds an extra (intercalary) month every two or three years, in a pattern that repeats every 19 years. Months commence at the full moon, and are followed by a “bright” fortnight. Each mid-month’s new moon kicks off a “dark” fortnight. The Hindu new year begins around the March equinox. The Hindu month that commences around mid-October on the Gregorian calendar is named Kartik or Kartika.

During its orbit around Earth, the moon varies its angle from the sun by about 12 degrees per day, resulting in 30 unique phases, half of them waxing and the other half waning. Each day of the Hindu lunar month is called a tithi, with each tithi bearing a name associated with a particular illuminated phase. On the day before new moon (or syzygy), the moon is less than 12 degrees west of the sun, and appears as a slim waning crescent. That tithi is called Amāvásyā (Sanskrit: अमावस्या), which literally translates to “no moon there”, since it’s rarely observable. The tithi for the day following new moon (slim waxing crescent) is Pratipada. Diwali always commences on Amāvásyā, the 15th day of Kartika.

Meteor Shower Update

Meteor season continues! Meteors from the Northern Taurids meteor shower, which appear worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually, reached its maximum last night (Saturday, November 12) in the Americas. You can continue to look for those colorful fireballs streaking away from Taurus (the Bull), and Jupiter this year, while they taper off during this week.

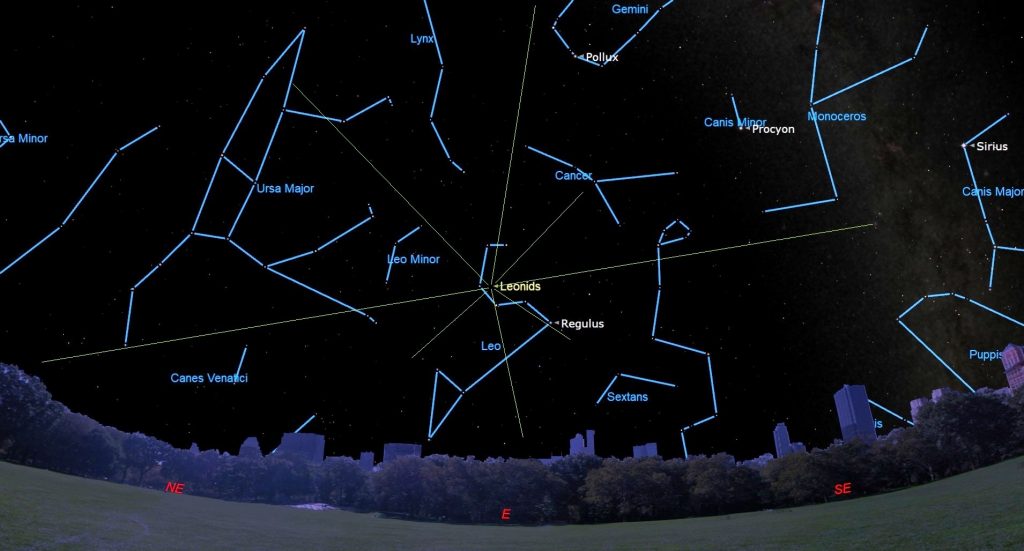

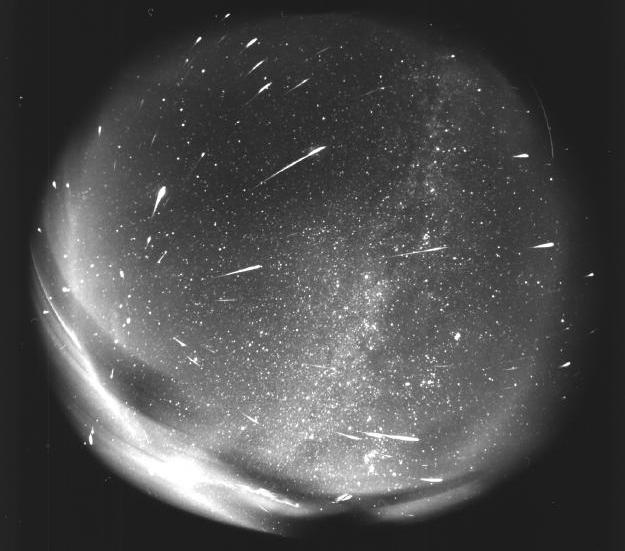

The Leonids Meteor Shower, which is derived from bits of material dropped when periodic Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle traverses the inner solar system every 33 years, runs from November 5 to December 2, annually. The peak of the shower, when up to 15 meteors per hour are typical, will occur on Friday night in the Americas. At that time Earth will be traveling through the densest part of the comet’s debris field. The particles hit the atmosphere over our heads at such a high speed that they ionize the air through friction, producing the streaks of light you see as “shooting stars”. Many Leonids have persistent trains and strong colour.

This shower is a worldwide event. The meteors can appear anywhere in a dark sky, but true Leonids will be travelling in a direction away from a location called the radiant that is positioned among the stars that form the head of Leo (the Lion). (The radiant’s location gives each shower its name.) Don’t focus your attention on the radiant – the meteors near it will have very short streaks because they are traveling directly towards you.

While you should see some Leonids after dusk on Friday evening – many with persistent trains – more meteors will be apparent on Saturday in the hours before dawn, when the radiant will be highest in the southeastern sky. For this year’s Leonids, the waxing crescent moon will set at around 8 pm local time on Friday, leaving the rest of night nice and dark for meteor-watching. If you venture out for a look, find a safe, dark location with lots of open sky, get comfortable, and just look up!

To preserve your dark adaptation, try to keep your phone tucked away. If you must look at it, turn the screen brightness to minimum, and/or enabled the red screen mode available on some models. Don’t try to see meteors through binoculars or a telescope – those instruments have a field of view that is too narrow. But you can take long exposure photos of the sky and catch the meteors’ streaks. If the peak night is cloudy, don’t despair – the surrounding dates will still deliver some meteors. Happy viewing!

I posted an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy stream all about meteors and meteorites on YouTube here.

Comets Update

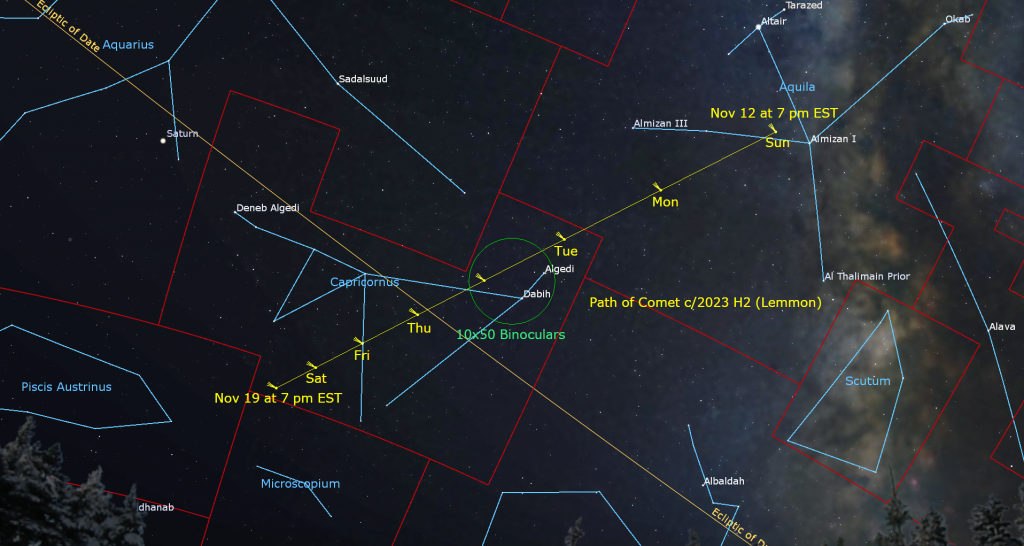

A comet named c/2023 H2 (Lemmon) passed closest to Earth on Friday, making it appear at its largest and brightest for the next few days. A number of astronomers have estimated its magnitude value to be 6, which is well within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes under dark skies.

The comet’s complicated-looking name tells us that the comet was discovered in 2023 during the two-week block H, which covers the second half of April. It was the 2nd comet discovered in that window. The comet was first photographed by the 1.5-meter reflector telescope of the Mount Lemmon Survey, which is part of the wider Catalina Sky Survey that operates from an observatory outside Tucson, Arizona.

Comets are speedy! This one will move by more than a palm’s width from one night to the next, travelling from upper right to lower left (or celestial south-southeast) across the constellations of Aquila (the Eagle) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) over this week. Those constellations are descending the southwestern sky after dusk, so you’ll want to look for the comet as soon as the sky darkens. The best viewing time will fall between about 6:30 and 9 pm local time, when the comet will be more than 20° above the horizon.

Tonight (Sunday) after dark in the Eastern Time zone the comet will sit a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° to the east) of the bright star named Almizan I (or Delta Aquilae) that marks Aquila’s heart. The comet will also move noticeably compared to the surrounding stars – by about the moon’s diameter every 3 hours – so observers in Europe and Africa should look closer to the star. Those in more westerly time zones should search farther to Almizan’s left.

On Wednesday the comet will pass two finger widths to the left of Capricornus’ bright stars Dabih and Algedi. From that point we run out of bright signposts to assist our search. By then the comet’s brightness will be rapidly dropping off.

Expect to see a faint grey fuzzy patch. Comets frequently look greenish when viewed in a big telescope or in a long exposure photograph. That colour is produced when diatomic carbon released from the comet’s icy snowball core is ionized by solar radiation. You may also pick out a small tail extending to the upper left (celestial northeast).

For those of you with larger telescope and/or astrophotography setups, a periodic comet named 103P/Hartley is available in the southern sky before dawn. This one, which is about magnitude 10 and fading, will be travelling much more slowly southward through western Hydra (the Snake). This week it will pass through a group of galaxies that includes NGC 2708 and NGC 2695, plus the double star named LSC 120.

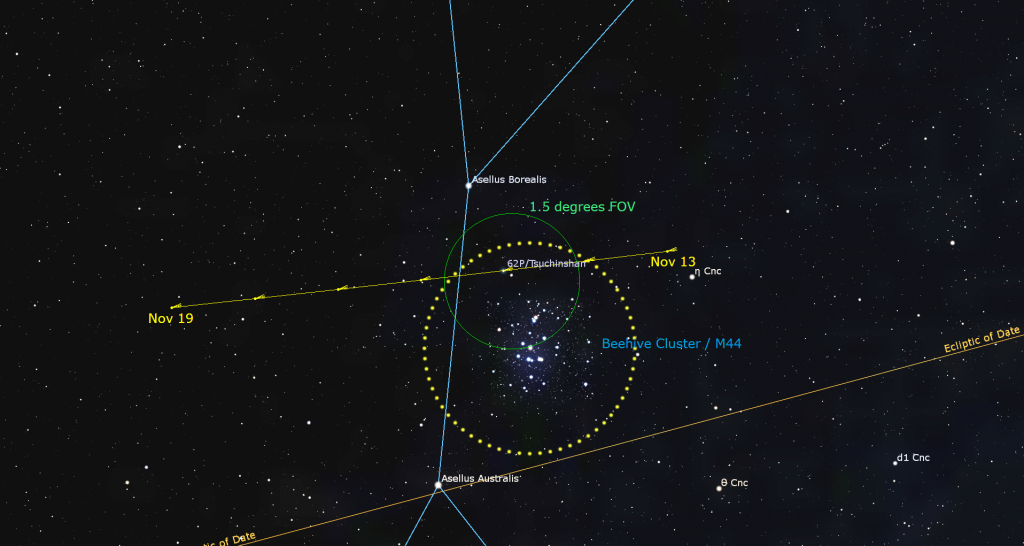

Finally, staying with the southern sky in morning, the magnitude 10.5 comet named 62P/Tsuchinshan will pass the northern outskirts of the big, bright Beehive Cluster (or Messier 44) in Cancer (the Crab) on Wednesday morning, but you can capture the comet and cluster on Tuesday and Thursday, too.

The Moon

The moon will grace our evening skies worldwide this week, but it won’t really affect stargazers until the coming weekend. Even then, Earth’s natural night-light will be only a crescent sinking low in the west after mid-evening. That will give us plenty of time to peruse the best sights of the northerly (in the celestial sense) summer constellations after dusk, the autumn constellations through the evening, and the winter sky starting around midnight.

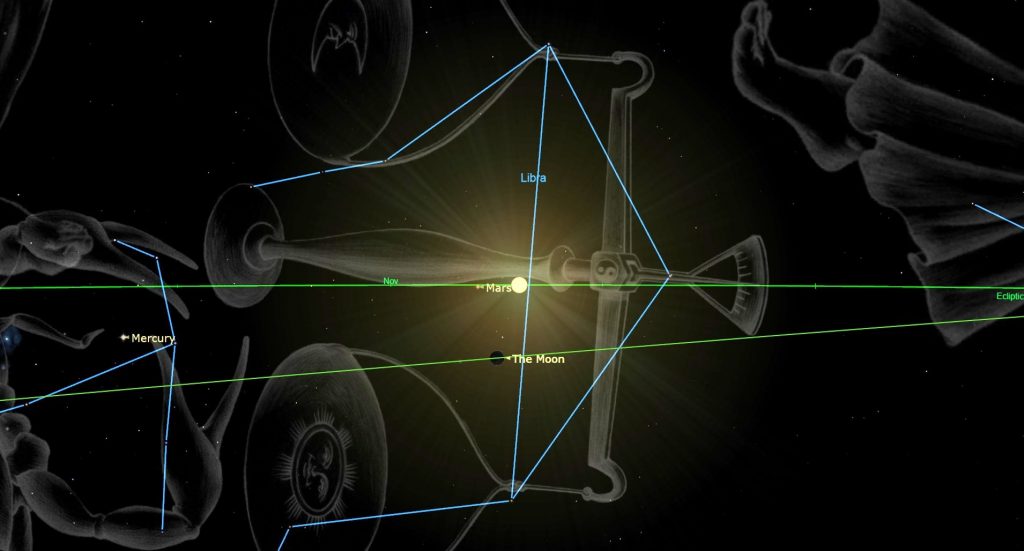

Today (Sunday) the old moon will be approaching the sun and therefore hidden from view. The moon will reach its new moon phase on Monday, November 13 at 4:27 am EST, 1:27 am PST, or 09:27 Greenwich Mean Time. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Libra (the Scales) and 2.5° below (south of) the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day (except during a solar eclipse). However…

At this time of year the ecliptic is very slanted at sunset for everyone situated at mid-northern latitudes on Earth. That, plus the fact that the moon’s orbit is nearly at its maximum range south of the ecliptic, will hold the moon very low in the sky. Despite it being 18° east of the sun on Tuesday, the moon will set just minutes later.

If you are lucky enough to live close to the tropics, where the ecliptic well be much more upright at sunset, you can look just above the southwestern horizon to see the very slender crescent of the young moon shining several finger widths to the left (or 4° to the celestial southeast) of Mercury. That will make the pair close enough to share the view in binoculars, but delay your search until the sun has completely set.

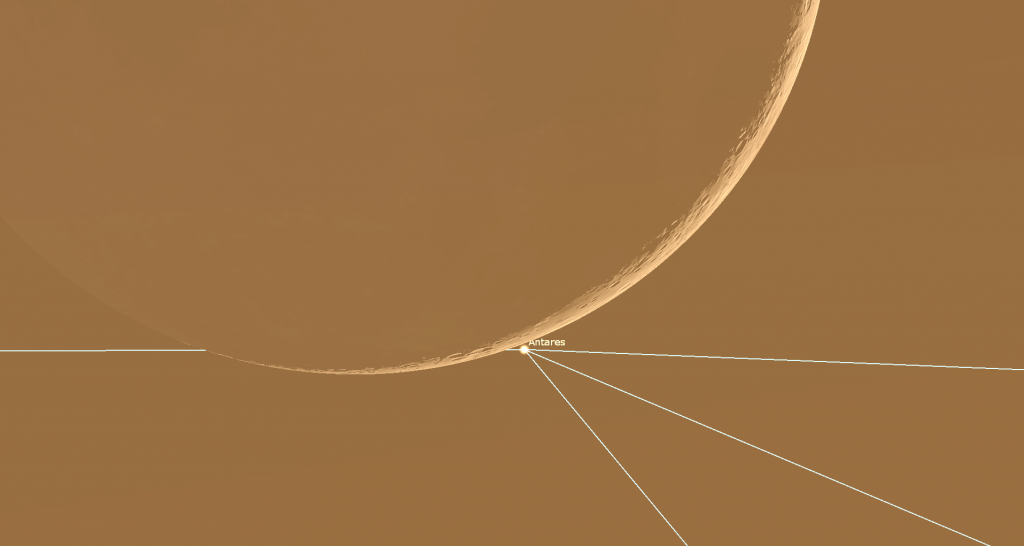

Meanwhile, on Tuesday the moon will also be positioned very near to Scorpius’ bright star Antares. The unlit limb of the slender, 2.7%-illuminated crescent moon will cross in front of, or occult, Antares around 3:50 pm EST or 20:52 GMT. The event will happen in daylight or twilight for observers in the continental USA and Canada, northern Central America, the northern Caribbean, and Bermuda. If the moon has not yet sunk too low where you live, try to glimpse Antares emerging from behind the moon’s lit edge around 5:05 pm EST or 22:05 GTM. Start watching a few minutes before each time quoted. Please take care to avoid aiming your optics towards the sun, which may still be above the horizon.

The crescent moon will become easier to see, though still low in the southwest, on Wednesday. On Thursday evening, the healthy crescent of the waxing moon will finally swing east enough of the sun to be able to shine in a darkening sky inside the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) after dusk. Watch for Earthshine, also known as the Ashen Glow and “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The phenomenon appears for several days after each new moon, but is strongest in springtime at mid-northern latitudes, when the moon is positioned directly above the sun when it sets.

The moon will remain within Sagittarius (the Archer) on Friday and then move through Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) on the weekend. Have the binoculars handy or telescope set outside to cool off during dinner time so that you can enjoy the spectacular vistas of the lunar terrain lit by slanted sunlight along the curved pole-to-pole terminator each evening. On Saturday night, the terminator will fall just to the west of a trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of round, gray Mare Nectaris to their left (or lunar east). You can tell what order those craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower right (lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

On next Sunday night, the yellowish dot of Saturn will shine to the upper left of the nearly half-illuminated moon. Get ready for some lunar-planetary conjunctions! Over a week starting next Sunday evening, November 19, the waxing moon will visit four planets in succession – Saturn, Neptune, Jupiter, and Uranus. I’ll share more about that next week.

The Planets

As we move more deeply into autumn at mid-northern latitudes, the overnight ecliptic gets lifted higher into the sky while the sun, on the opposite side of that imaginary ring around Earth, gets pushed lower at noontime. The benefit of that change is to raise the planets strung along the ecliptic to a position higher in the sky during evening, where they show with more clarity through telescopes. The earlier sunsets, which are going to arrive around 4:53 pm in Toronto this week, are also delivering lots more viewing time.

As I mentioned above, Mercury is lurking above the southwestern horizon for a short time after sunset this week, but its position below a very slanted ecliptic will hold it too low to be seen easily from mid-northern locales. If you live in the southern USA, or in the tropics, or in the Southern Hemisphere, you can seek out Mercury’s brightening, magnitude -0.4 speck above the sunset point on the horizon after the sun has completely set – but don’t search with binoculars or a telescope until the sun is gone from view. Mars will pass behind the sun, on the far side of the solar system from Earth, on November 17-18, disrupting the radio signals to our robotic Mars explorers.

The two gas giant planets Saturn and Jupiter will dominate the evening sky worldwide for another couple of months – each pursued by an ice giant planet.

The yellowish dot of Saturn will emerge from the evening twilight in the lower part of the southeastern sky at dusk. It will culminate in the south around 7 pm local time (its best telescope viewing time) and then sink westward to set around midnight. Although Saturn is positioned within the borders of Aquarius, most of the Water-Bearer’s stars are arrayed off to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east). The faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) are to Saturn’s lower right (or west).

Any size, style, or brand of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air isn’t too turbulent, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the large outer A Ring from the large inner B Ring. I wrote more about the rings here. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left of Saturn (celestial east) tonight to just to the lower right of the planet (celestial southwest) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

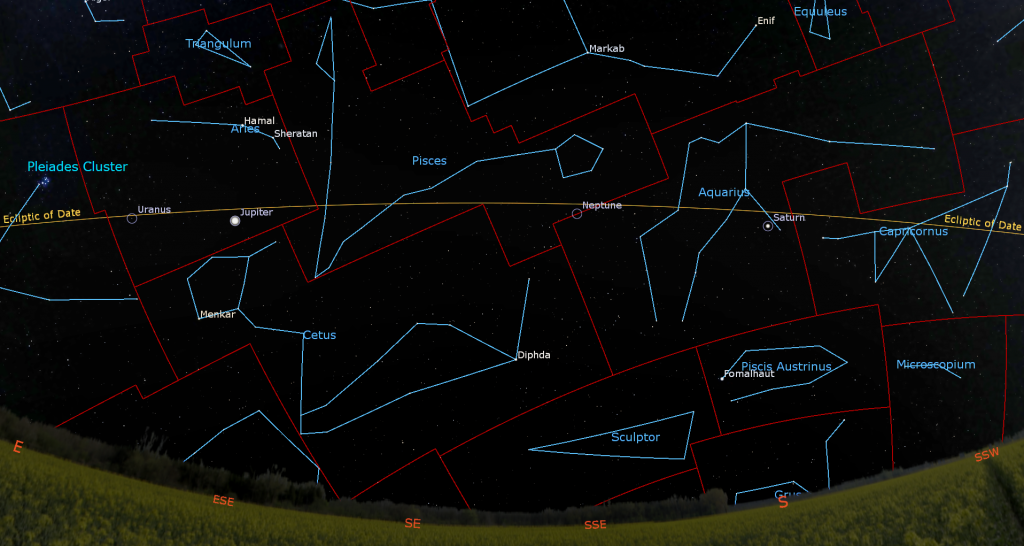

Saturn is preceding the far fainter ice giant planet Neptune across the sky each night. This week Neptune will be located 2.5 fist diameters to Saturn’s upper left, or 25° to its celestial northeast. The diurnal rotation of the sky – the way things tilt as they cross from east to west – will cause Neptune to be lifted increasingly higher than Saturn until they set. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is visible in backyard telescopes, especially when the blue planet is highest, between dusk and midnight local time. Good binoculars can show Neptune if your sky is very dark.

Recently past opposition and peak visibility for this year, the giant planet Jupiter will gleam above the eastern horizon after sunset and then catch the eye while it crosses the sky all night long. Jupiter will climb to a position relatively high in the southern sky in late evening and then set in the west around 6 am local time. The big planet will look best in a telescope while it is higher between 7 pm to 4 am each night.

Hamal and Sheratan the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), are shining a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter this year. If you are outside on a clear evening this week, and your light pollution isn’t too bad, Aries’ stars will be far out-matched by the bright little clump of the Pleiades cluster positioned to Jupiter’s lower left and a bright cloud of stars surrounding Mirfak, the brightest star in Perseus (the Hero). I wrote about the cluster last week. (Next year, Jupiter’s 12-year orbit will place it into Taurus (the Bull).)

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line flanking the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another.

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. It’ll appear around midnight on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday, and before dawn on Tuesday and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday evening, November 13, Io will lead its shadow across Jupiter from 7:22 to 9:31 pm EST (or 00:22 to 02:31 GMT). Ganymede’s large shadow will venture across Jupiter’s southern latitudes, on Friday evening, November 17 from 5:05 pm to 6:42 pm EST (or 22:05 to 23:42 GMT). Europa’s shadow will venture across Jupiter’s southern latitudes on Saturday morning, November 18 from 1:27 to 3:44 am EST (or 06:27 to 08:44 GMT on November 19). Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region with the Great Red Spot on Sunday morning, November 19 from 2:48 to 4:57 am EST (or 07:48 to 09:57 GMT). Each of those moons will pop into view when it moves off Jupiter at the end of its shadow transit. (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

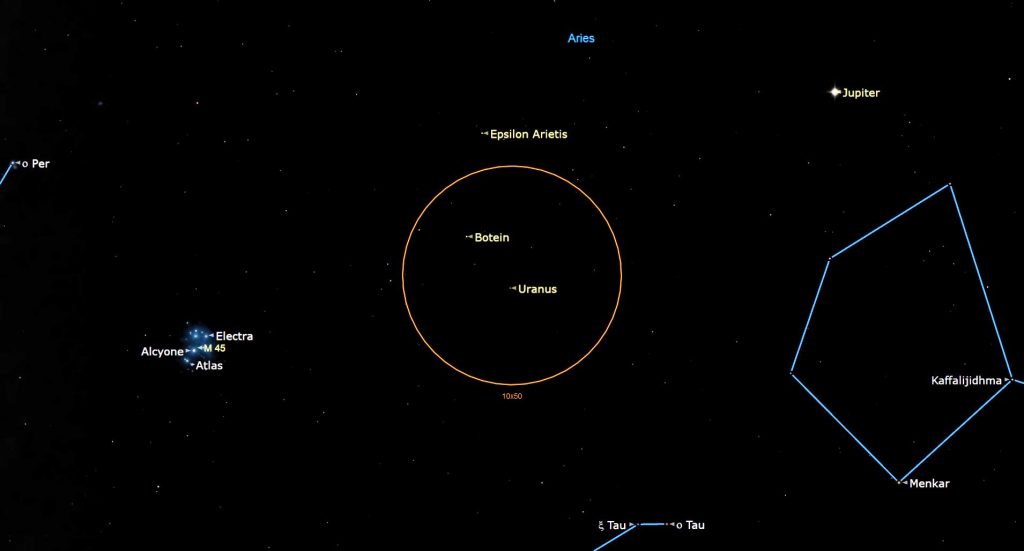

Jupiter’s own pursuer across the night sky is Uranus. This week the blue-green ice giant planet will be positioned a generous fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 12° to the celestial east), on the Aries side of its border with Taurus. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus to the same height as Jupiter around 10 pm local time and then higher still, later. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ upper left (or 10° to the celestial northeast).

On Monday, November 13 Uranus will reach opposition – the night of the year when it is closest to Earth at a distance of 2.78 billion km or 155 light-minutes. The planet will shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.62 as it crosses the sky all night long, making it readily visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Some people have been able to spot Uranus with their unaided eyes. Can you? Uranus small, blue-green dot will also appear slightly larger in telescopes for about a week centered on opposition night. The best views of Uranus will be available between 7 pm and 5 am local time. Uranus has been moving slowly retrograde westwards through southeastern Aries. This week it will be positioned roughly midway between Jupiter and the Pleiades Star Cluster aka Messier 45. Uranus’ location 2 degrees south of the medium-bright stars Botein and Epsilon Arietis will aid in your binoculars search.

Brilliant Venus and Jupiter have been mirroring one another in the pre-dawn sky. If you head outside on a clear morning around 4:40 am local time this week, the two planets will be positioned at about the same height in the sky, with Venus due east and Jupiter due west. Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, will shine between them in the southern sky.

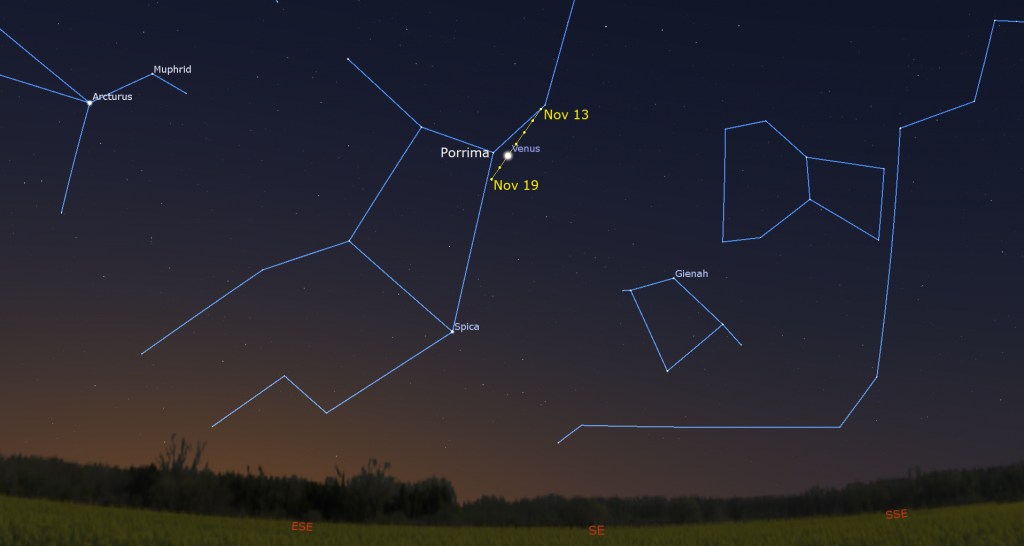

Long after Jupiter sinks out of sight, the very bright, magnitude -4.4 planet will continue to climb the eastern sky (until the rising sun hides it). Due to its swing sunward, Venus will shift a little lower each morning. Viewed through a telescope, Venus will show a waxing gibbous disk spanning 19.5 arc-seconds. On Friday morning, Venus will shine just a finger’s width to the right of Porrima, a terrific and easily split double star in Virgo.

Admiring Andromeda

During the fall, I like to showcase the constellations involved in the Greek mythological story of Perseus and Andromeda. If you missed last week’s tour of Andromeda, which will still be worthy of your attention this week, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, November 15, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting. The speaker will be Rajveer Seehra, Astrophysics student, University of Manitoba. His topic will be Galactic Evolution: Unveiling the Structure of Galaxies. Check here for details and watch the presentation at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

On Friday afternoon, November 17 from noon to 2 pm EST, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sun Fun. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 5 and up and runs rain or shine, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Friday, November 17 from 7 pm to 9 pm, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is here.

Spend an afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Saturday afternoon, November 25, visitors 6 years old and up can join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Please note that all guests will sit on a clean floor. A registered adult must accompany all registered participants under the age of 16. We run one session at 1 pm and another one at 2:45 pm. More information and the registration links are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!