The Planet Parade Adds Another, the Moon Moves into Morning, and We Eye Evening Orion!

This image of Orion was taken by Alan Dyer on January 2, 2020 in the moonlight from a first quarter Moon, with orange Betelgeuse (top left) much dimmer than usual, a little brighter than Bellatrix at right. Enjoy more of Alan’s terrific work at https://www.amazingsky.com/

Hello, mid-February Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 16th, 2025 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Instagram and Bluesky as astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

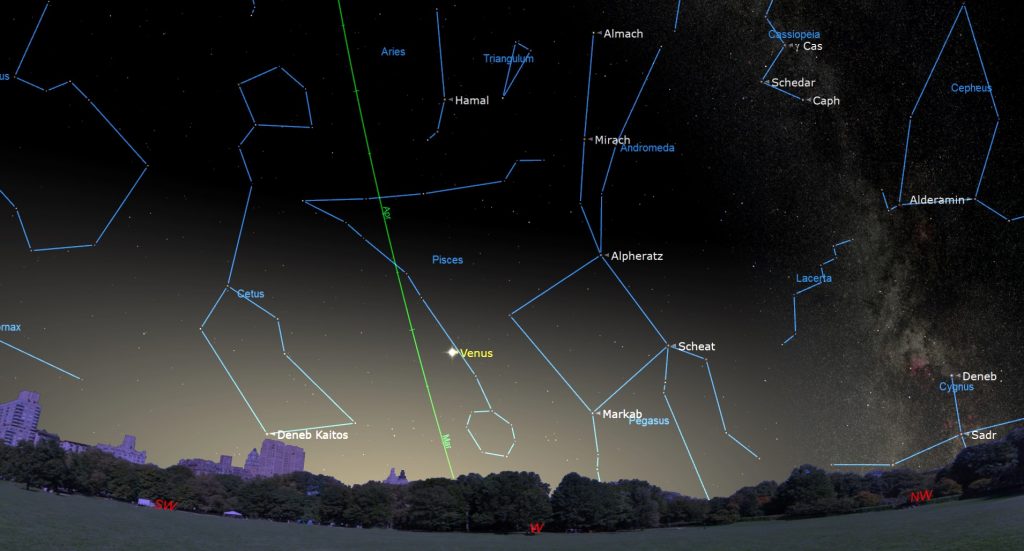

The moon will vacate the evening sky this week and next, allowing us to resume our winter stargazing – so I share a detailed tour of Orion’s stars and the many treasures he hosts that are easily seen by anyone. Venus still gleams near maximum brightness in the west above Neptune, Saturn, and now Mercury, while Jupiter and Mars shine on high with faint Uranus. Read on for your Skylights!

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a mid-northern latitude location where the sky is free from light pollution, you might be able to spot a phenomenon called the zodiacal light during the two weeks that precede the new moon arriving on February 27. After the evening twilight has faded, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below the planets Venus and Saturn. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. I posted a nice photo of it here.

Eyeing Orion

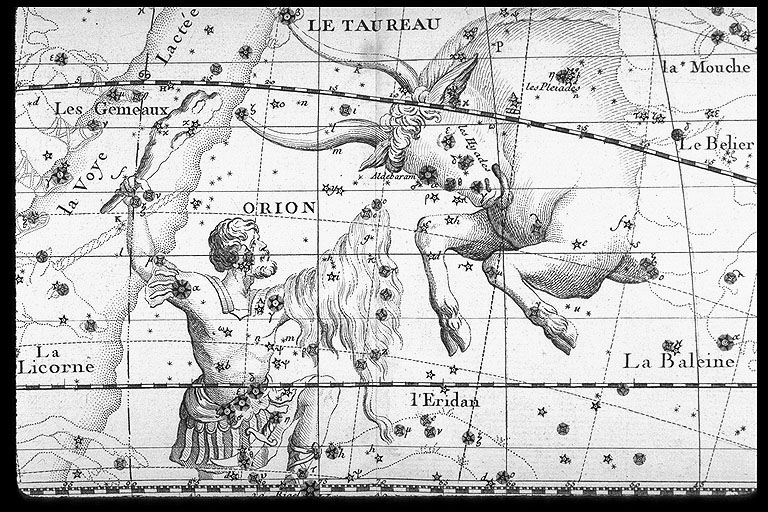

Every year during winter, the southern evening sky is dominated by the eye-catching constellation of Orion (the Hunter) and his famous three-starred belt. Orion contains some of the sky’s most spectacular sights – whether you are using your unaided eyes, binoculars, or telescopes of any size! Orion’s spectacular stars, and the bright nebulas in his sword and belt, make cold winter nights much more rewarding for skywatchers. So let’s bundle up against the winter chill and take a tour of the hunter while the moon is out of the evening sky this week and next!

The constellation of Orion is well-known for several reasons. It straddles the Celestial Equator, making it visible from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Most of its stars are bright enough to see with unaided eyes, even under light-polluted skies. And the constellation obviously represents a human figure.

Orion is surrounded by Taurus (the Bull) to his upper right (celestial northwest), Gemini (the Twins) to his upper left (northeast), Monoceros (the Unicorn) on his left (east), Lepus (the Rabbit) below him (south), and Eridanus (the River) towards his lower right (southwest). Only for winter of 2025, the brilliant planet Jupiter will be shining to Orion’s upper right.

The hunter has traditionally been depicted as kneeling. His eastern arm is raised and holds a club. His western arm is outstretched, and his hand holds a lion’s pelt, or a shield. Orion is a medium-sized constellation measuring about 30° (or three outstretched fist widths) from the tip of his club to his toes or knees, and 20° from his eastern elbow to the lion’s pelt. In early evening in mid-February, Orion is halfway up the southern sky, leaning a little to the left for observers viewing him in the Northern Hemisphere. As the evening wears on, Orion stands upright and then tilts to the right before he sets at about 2 am local time.

The constellation was recorded by Babylonians as the Heavenly Shepherd (where his club is a crook). The Egyptians added the stars of Lepus to form the god Sah, which was associated with the deity representing the star Sirius. The muslims called him “al-jabbar” the giant. The Polynesians saw a Cat’s Cradle game in Orion’s stars. The Maori incorporated Orion’s belt into the stern of their great ocean-going canoe, Te Waka O Tamarereti.

In Greek mythology, Orion was Prion the hunter, the son of Poseidon. When Prion threatened to hunt and kill all the animals in the world, Earth-mother Gaia sent Scorpius to sting him to death. But Ophiuchus (the Water-Bearer) used medicine to save Prion. Now, Orion and Scorpius sit on opposite sides of the sky. Orion is in the winter evening sky and Scorpius is in the winter morning sky – with Ophiuchus stepping on the scorpion from above. Orion is mentioned several times in the Bible, and as Menelvagor “the Swordsman of the Sky” in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

The Ojibwe and related indigenous groups of North America associate Orion’s stars with the constellation of Biboonikeonini (”Bih-BOON-koh-nih-NIH”), the Winter-Maker. They envision him with longer arms – so that his hands hold the bright stars Procyon on the east and Aldebaran on the west.

Not surprisingly, many cultures have also assigned meaning to the distinctive row of three regularly spaced stars that mark Orion’s Belt. Scandinavian countries have seen a distaff, a scythe, and a sword. Predominantly Catholic countries referred to those three stars as The Three Mary’s (as featured in the New Testament). In the Middle East, his belt has been identified as The Three Kings or Magi. In China, it is known as The Weighing Beam and the Three Stars. In fact, the top portion of the Chinese character, 參 (shēn) has three identical symbols representing those three stars. The Lakota people called his belt the Bison’s Spine – with surrounding stars and nearby constellations forming the rest of a great bison in their winter sky. When viewed from the Southern Hemisphere, Orion is upside-down. His belt and sword combine to form the shape of a frying pan! Try bending over and looking at him upside-down.

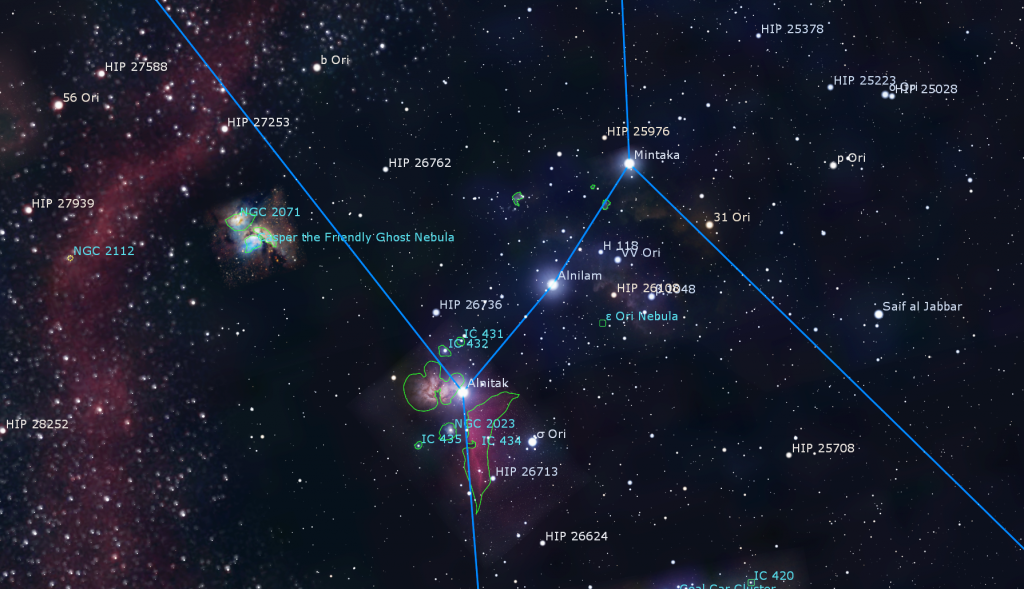

From left to right (or east to west in the Northern Hemisphere), the three belt stars are named Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka. While they appear similar, Alnitak is bluer, Mintaka is dimmer, and Alnilam is MUCH farther away.

In a telescope, Alnitak (Arabic for “the Girdle”) is revealed to be a very tight double star. The larger, main star of Alnitak’s pair is a blue supergiant star located about 820 light-years from our solar system. The star emits tremendous amounts of ultraviolet light. Its surface temperature is a scorching 31,000 Kelvins, which is essentially the same as 31,000° C at those extremes! For comparison, our little yellow sun’s temperature is a mere 6,200 K! Alnitak’s dimmer partner is orbiting the main star once every 1,500 years!

The belt’s middle star, Alnilam (“String of Pearls”), is another large and very hot, blue-white star. It’s located about twice as far away from us than the two other belt stars. Aging rapidly and nearing the end of its hydrogen supply, Alnilam is expected to become a red supergiant, the pre-cursor to a supernova blast, at any time. And since the star is more than 1,900 light years away from us – that explosion may already have happened!

The belt’s westernmost star, called Mintaka (“Belt”), is also a double star when viewed in a telescope. In fact, there are at least four stars making up what we see as Mintaka. The brightest one has a partner that orbits it in an eclipsing binary configuration that causes the star to vary in brightness for 18 hours every 5.73 days. The dominant stars in Mintaka’s family gathering are hot, blue giants. The group is located about 900 light years away from our solar system. If you look carefully, Mintaka is actually quite a bit dimmer than Alnitak and Alnilam. At the same time, look for a large, upright letter-S shape composed of dim stars in the space between Alnilam and Mintaka.

The bright, orange-coloured star named Betelgeuse marks Orion’s eastern armpit or shoulder. That funny-sounding name comes from the Arabic expressions “Ibṭ al-Jauzā”, meaning “the Armpit of Jauza”, or “Yad al-Jauzā”, “the Hand of Jauza”. Jauza was the Arabic name for the person the Arabs saw depicted in the Orion constellation. In Chinese, Betelgeuse is called 参宿四 Sānsù Sì, which translates to “The Fourth Star of the constellation of Three Stars”.

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant star located about 500 light-years away. If Betelgeuse replaced the sun in our solar system, all the inner planets out to Mars would be inside the star! Despite an age much less than our sun (it is of a type that matures dramatically faster), astronomers think Betelgeuse is approaching the end of its life. It is massive enough to explode as a Type II Supernova.

Normally, Betelgeuse ranks as the tenth brightest star in all the night sky. But in the winter of 2019-2020 it dimmed dramatically. While Betelgeuse has been known to dim and brighten throughout the many years that astronomers have been recording its brightness, this recent dimming was far below what is typically observed. Some thought we might be seeing indications that the end is near. After several months, it recovered most of its brightness. Astronomers now theorize that an encircling cloud of opaque dust temporarily passed in front of the star, dimming its light. Since it takes about 500 years for light to reach us from Betelgeuse, it could already have exploded! If it does blow up, Earth is in no danger. We’ll just be treated to a spectacularly bright point of light for days or weeks.

Rigel is the hot blue star sitting to the lower right (or southwest) of Orion’s belt. Despite being located much farther away from us (about 860 light-years) than Betelgeuse, Rigel is approximately the same visual brightness as Betelgeuse – meaning that Rigel emits considerably more visible light than Betelgeuse, a phenomenon that astronomers call high luminosity. Rigel, too, is a supergiant star, and it has a surface temperature of 11,000 K! In a good telescope, a small companion star can be spotted very close beside Rigel. In Arabic, Rigel means “the Foot of the Great One”. In China, Rigel is known as 参宿七 (Sānsù Qī), “The Seventh of the Three Stars”.

Orion’s western shoulder is marked by the bright star Bellatrix, which translates as “Amazon Star”, after the warrior women of legend. Bellatrix is about 250 light years away from us, and burns at a blistering hot 21,500 K. It, too, is well along in its life cycle, and is expected to soon enter its next phase of evolution and turn an orange colour.

Above and between Orion’s shoulders is an open cluster of stars, 1,305 light-years distant, that forms his head. The brightest star in the group is named Meissa (“the Shining One”). Use binoculars or a telescope to see them as individuals. How many stars can you count? A backyard telescope will show you Meissa’s close partner. Some star charts call the grouping the Lambda Orionis Cluster, after Meissa’s Bayer designation λ Ori.

Completing our circuit of Orion’s main body, the eastern foot or knee of Orion is the mis-named star Saiph or “Sword of the Giant”. Saiph is another hot, blue white star, with a surface temperature of 26,500 K. It, too, is approaching the transition to its old, red supergiant stage.

The lion’s pelt, or shield, that Orion is holding is composed of a crooked line of stars, arranged up and down, located on Orion’s right-hand (or western) side less than a fist’s diameter to the right of Bellatrix. The brightest star in the middle of the string is named Tabit (“the Endurer”). This star’s Bayer designation is Pi Orionis (or π Ori). Unusually, someone decided that every star in that line should be a Pi star, naming them π1 through π6 Orionis.

On the opposite side of the constellation, Orion’s upraised club dips into the Milky Way. As you move follow it higher, the pairs of stars that define it move wider apart. Use your binoculars to reveal the rich Milky Way star fields there.

We can use Orion’s stars as pointers to other ones. Extending the line of the belt stars to the upper right (or celestial west) leads to the bright, orange-ish star Aldebaran in Taurus, the Bull. Heading two fist diameters in the opposite direction leads you to the “Dog-star” Sirius, the brightest star in the entire night sky. A line drawn from Bellatrix to Betelgeuse points to Sirius’ bright puppy, the star Procyon. Finally, the line extending from Rigel upward through Betelgeuse leads to the star Castor and its fraternal twin Pollux, each the head of Gemini (the Twins).

Orion’s spectacular sword is one of winter’s true astronomical treats. The sword is located a few finger widths below Orion’s belt. Unaided eyes can generally detect three patches of light in Orion’s sword, but binoculars or a telescope will reveal that the middle object is not a single star at all, but a bright knot of glowing gas and stars known as The Orion Nebula or the Great Nebula in Orion, and Messier 42 (or M42, for short).

The Orion Nebula is one of the brightest nebulae in the entire night sky and, at 1,400 light-years from our solar system, it is one of the closest star-forming nurseries to us. It’s enormous. Under a very dark sky, the nebula can be traced over an area equivalent to four full moons! When you see knots of pink color in photos of other galaxies, you are seeing objects like M42.

Buried in the core of the Orion Nebula is a tight clump of stars collectively designated Theta Orionis (Orionis is Latin for “of Orion”), but better known as the Trapezium – because the brightest four stars occupy the corners of a trapezoid shape. Even a small telescope should be able to pick out this four-star asterism – but a night of calm air and a larger aperture telescope will reveal two additional faint stars in the trapezium. The trapezium stars are hot, young O- and B-type stars that are emitting intense amounts of ultraviolet radiation. Their radiation causes the Hydrogen gas they are embedded within to shine brightly as red light. At the same time, some of their light is scattered by surrounding dust, producing blue light. The combination of red and blue is why there is so much purple and pink in colour images of the nebula.

Within the nebula, astronomers have detected many young (about 100,000 years old) concentrations of collapsing gas called proplyds that should one day form solar systems. These objects give us a glimpse into how our own sun and planets formed.

Stargazers have long known about the trapezium stars in the nebula’s core, but detection of the nebulosity around them required the invention of telescopes in the early 1600’s. In the 1700’s, Charles Messier and Edmund Halley (both famous comet observers) noted the nebula in their growing catalogues of “fuzzy” objects. In 1880, amateur astronomer Henry Draper imaged the nebula through an 11-inch refractor telescope, making it the first deep sky object to be photographed.

In your own small telescope, you should see the bright clump of trapezium stars surrounded by a ghostly grey shroud, complete with brighter veils and darker gaps. More photons would need to be delivered to your retina before colour would be observed, so try photographing it through your telescope, or using a camera/telephoto lens combination mounted on a tripod. Visually, start with low magnification and enjoy the extent of the cloud before zooming in on the tight asterism. Can you see four stars, or more? Just to the upper left of M42, you’ll find Messier 43, a separate lobe of the same nebula that has been separated by a band of opaque foreground dust. M43 surrounds a naked-eye star named Nu Orionis (or ν Ori).

While you’re touring the sword, look just below the nebula for a loose group of stars, located 1,300 light-years away from Earth, called Nair al Saif “the Bright One of the Sword”. The main star is a hot, bright star expected to explode in a supernova one day. It, too is surrounded by faint nebulosity. Astronomers believe that this star was gravitationally kicked out of the Hyades Cluster in Taurus about 2.5 million years ago.

Sweeping down the sword and toward the left (east) brings us to a star named Mizan Batil ath Thaalith (or d Orionis or 49 Orionis) at the tip of the sword. This magnitude 4.7 star is near the limit for unassisted visibility under moonless, suburban skies. About two finger widths to its right is another star of similar brightness, named Upsilon Orionis, or u Ori.

Moving upwards towards Orion’s belt, look half a finger’s width (or 30 arc-minutes – equal to the full moon’s diameter) above the Orion Nebula. Here you’ll find another clump of stars dominated by c Orionis and 45 Orionis. A larger telescope, or a long-exposure photograph, will reveal a bluish patch of nebulosity around them that contains darker lanes forming the shape of a figure, called the Running Man Nebula (NGC 1977). This is another case of dust and gas scattering blue light from those two stars.

Just above the Running Man sits a loose cluster of a few dozen stars called the Coal Car Cluster, or NGC 1981. It is best seen in binoculars. Next, we jump higher – most of the way towards Alnitak, the eastern-most (left-hand) belt star, to check out a beautiful little grouping of stars collectively called Sigma Orionis (σ Ori). What makes this a special treat is that, in a small telescope, we find about 10 stars the grouping. Check it out with your telescope – trust me, it’s a pretty sight! It’s a bit more than a finger’s width to the lower right of Alnitak.

Astrophotographers love to image the area around Alnitak because it sits just to the west (or right-hand side) of the Milky Way, and is loaded with gorgeous gas clouds and nebulae. Alnitak and the brighter stars around it all host reflection nebulas – dim bluish haloes caused by starlight scattering off of dust.

Immediately below (south of) Alnitak is the famous Horsehead Nebula (or NGC 2023). It’s a cloud of hydrogen that is being energized by radiation from Alnitak, producing an elongated wedge of red light in long exposure images. A foreground patch of opaque dust that forms a delightful sea-horse or chess-piece shaped silhouette on the nebula’s (left-hand) eastern edge. It’s not readily visible – unless you have very dark skies and a very large aperture telescope.

Just to the left of Alnitak is another object called the Flame Nebula, also known as the Maple Leaf Nebula, the Burning Bush Nebula, and NGC 2024. More energetic radiation from Alnitak is causing gas to glow. But this time, there’s a lot of dark dust mixed in, producing a unique shape.

Several bright emission nebulae are clumped about two finger widths to the upper left (or celestial north) of Alnitak. The brightest of these is Messier 78, the Casper the Friendly Ghost Nebula. The young stars buried within the gas and dust are producing the pinkish emissions and bluish reflections. Another similar object called the Monkey Head Nebula (or NGC 2175) sits way up beside the tip of Orion’s club.

Orion’s upraised club starts at reddish Betelgeuse, continues through medium-bright Mu Orionis, and then widens north of the magnitude 4.5 stars Xi and Nu Orionis. A delightful open cluster named NGC 2169 is positioned between those stars, but offset a little towards Betelgeuse. Shining at magnitude 5.9, the cluster might look like a double star in your binoculars. In any size of telescope look for a dozen stars sparkling within a compact area. They are arranged in two groups that appear to form the letters “LE” or the number “37” or a shopping cart. Your own impression may depend upon how your telescope orients the cluster. I noted several doubles and some nice variation in the star colours.

A very nice open cluster designated NGC 1662 is located a thumb’s width to the right (or 1.6° to the celestial WNW) of Pi1 Orionis, the top star in Orion’s shield. The magnitude 6.4 cluster should be visible as a small patch in 10×50 binoculars. In any size of telescope, look for a tiny, diamond-shaped asterism flanked by a row of blue and yellow stars. It resembles a bird riding an air current, or maybe the lights of a Klingon battle cruiser. No danger, though – it is 1,450 light-years away from our sun.

I think you’ll agree that Orion is indeed a celestial treat for everyone to enjoy!

The Moon

Just a few days past its full phase, the moon will begin this week shining brightly worldwide – but you’ll only see it surrounded by the spring constellations in the hours after midnight and then in morning daylight. The next two weeks of moonless evenings will be ideal for stargazing.

Tonight (Sunday) the 80%-illuminated moon will clear the trees in the east near Spica, the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden), after about midnight. Watch for it in low in the southwestern sky on your way to school or work.

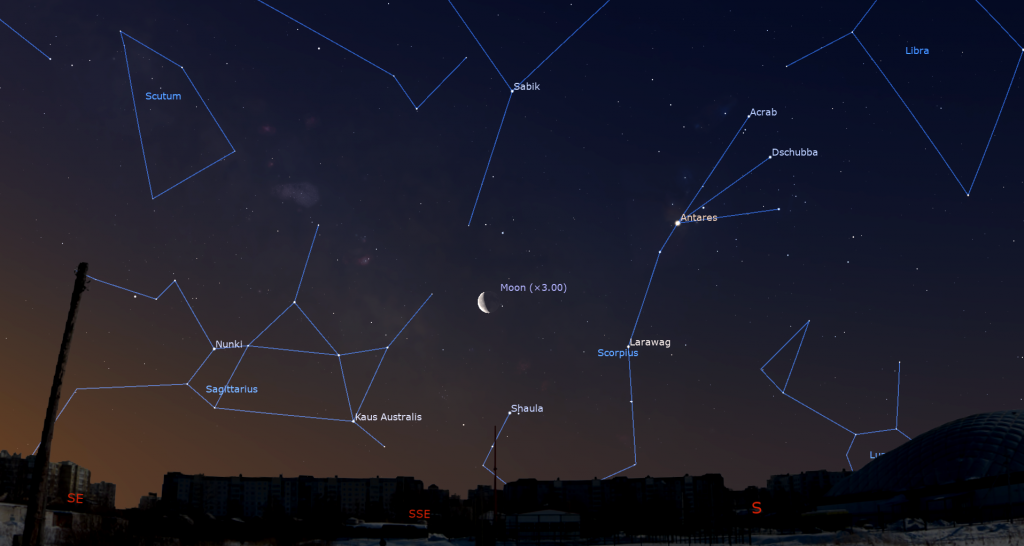

As the moon approaches the morning sun, it will rise about an hour later each day, wane in phase, and linger longer into daylight. It will spend Tuesday morning in Virgo, then Wednesday and Thursday in Libra (the Scales). If you are outside by about 6 am local time on Thursday, watch for the bright reddish star Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion) twinkling to the moon’s left. The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Thursday, February 20 at 12:32 pm EST or 9:32 am PST, or 17:32 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third quarter (or last quarter) phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side.

Early risers will enjoy its waning crescent before sunrise towards the end of the week. On Friday morning the moon’s pretty crescent will shine just to Antares’ lower left (or celestial southeast). A smaller star named Tau Scorpii will be tucked in close to the moon, or temporarily hidden behind it, if you live in a more westerly time zone. Hours earlier, observers located on Easter Island and southern South America can watch the moon cross in front of (or occult) Antares with unaided eyes, binoculars, and telescopes. Use an app like Stellarium or Starwalk 2 or Sky Safari to look up the timings where you live.

On Saturday morning the crescent moon will pose between the Scorpion and the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). It will slide inside the teapot on next Sunday morning.

The Planets

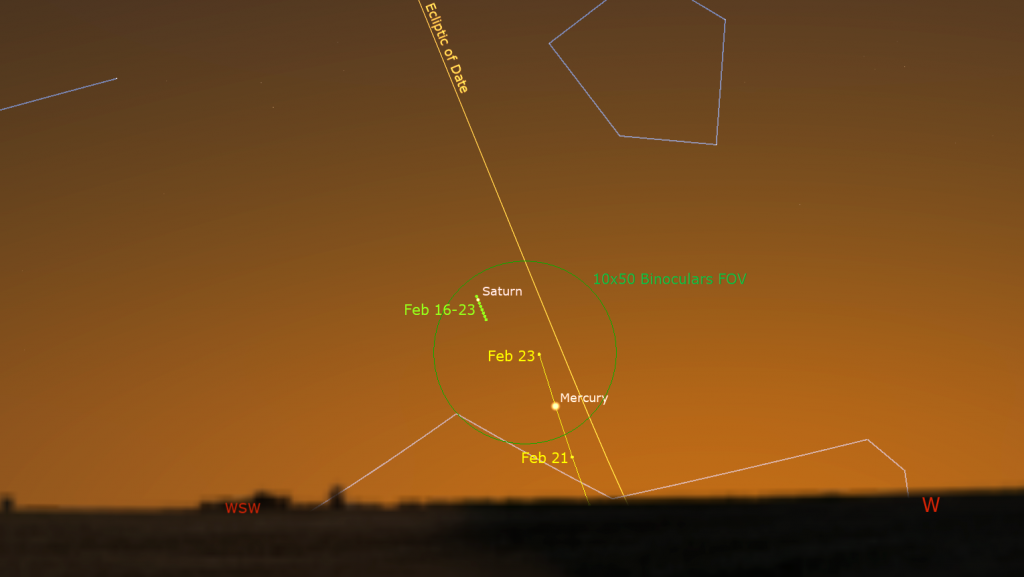

In theory, the ongoing planet parade will increase to seven planets this week because speedy Mercury, fresh from its solar conjunction, will be setting shortly after the sun every evening for the next few weeks. Though it will be increasing its distance from the sun and lingering a little longer above the western horizon every day, Mercury will be almost impossible to see until about mid-week – but all seven planets will be above the horizon, at least for a while.

While Mercury is moving higher every night, Earth’s motion around the sun will be causing Saturn and the rest of the stars in the western sky to drop lower – leading to a twilight planetary conjunction of Saturn and Mercury. The two planets will be closest to one another next Monday, but you can view them together in binoculars from Saturday onwards.

On Saturday, Mercury will be located several finger widths to the lower right (or 4° to the celestial WSW) of 9 times fainter Saturn. Both planets will be challenged by the twilit sky around them and the haze above the horizon. Wait until the sun has fully disappeared before using binoculars or a telescope. Next Sunday their separation will be smaller. I’ll talk more about them next week.

If you do manage to catch Mercury in your telescope, you will see it has a gibbous, rugby ball shape. Meanwhile, Saturn’s rings will appear as a thin line through the planet. This week Saturn will set at about 7:20 pm local time, just as the sky is darkening. In the eastern pre-dawn sky in late March, Saturn’s rings will be nearly invisible to us when their plane points toward Earth for a while.

The big celestial showpiece in evening will continue to be Venus – for now. Our sister planet reached maximum brilliance on Friday, but Venus will rapidly drop sunward in the western sky over the next few weeks, so enjoy it while you still can. Venus and the surrounding stars of Pisces (the Fishes) will meet the treetops around 8:15 pm local time. To see the planet’s crescent shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at Venus while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened. Good binoculars can hint at Venus’ non-round shape, too.

Faint blue Neptune is located low in the western sky below Venus and above Saturn, but it’s observable only through a telescope right after the sky darkens.

Very bright Jupiter will appear high in the southeastern sky even before the sky has fully darkened. It will climb highest, due south, at about 7 pm local time, and then set during the wee hours. This month, Jupiter is positioned above the Hyades Cluster, the triangular group of stars that form the face of Taurus (the Bull). Those stars, all born of the same gas cloud long ago are traveling through the Milky Way together. They are about 150 light-years away from us. Taurus’ brightest star, reddish Aldebaran, which marks the eye of the beast at the lower corner of the V is a foreground star only 67 light-years away.

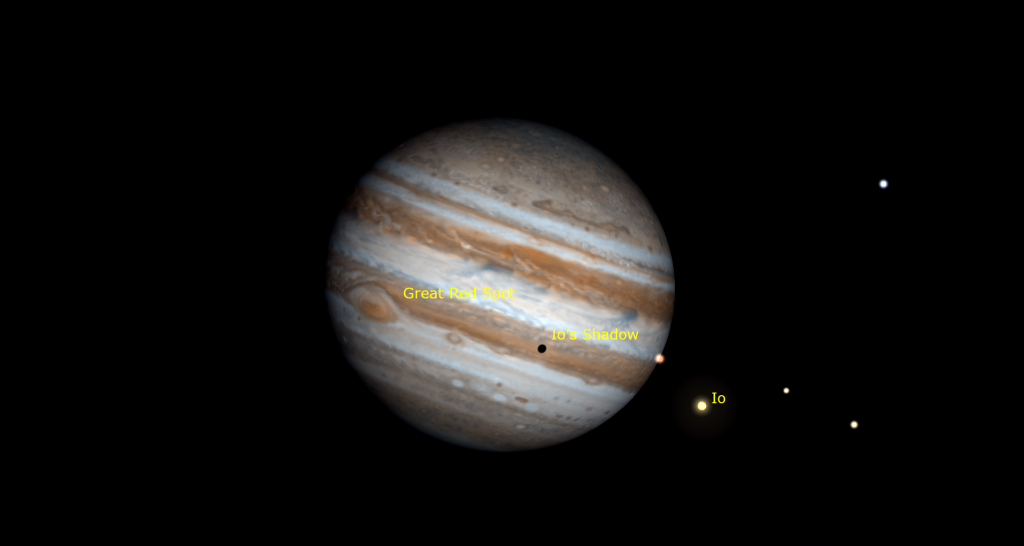

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a large disk striped with brownish dark belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, and also after 10 pm Eastern time on Monday and Wednesday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Io’s small shadow will lead the Great Red Spot across Jupiter on Monday evening, February 17 between 6:11 pm and 8:20 pm EST (or 23:11 to 01:20 GMT) and again with the spot on next Sunday morning, February 23 starting at 1:38 am EST.

Uranus is located near Jupiter and the Pleiades this year. The distant ice giant planet will be observable from the end of evening twilight until midnight. If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths to the left (or southeast of) them. In a backyard telescope, it will appear as a fairly prominent, non-twinkling blue-green dot.

Mars is at the eastern end of the planet parade – nearly two-thirds of the sky away from Mercury and Saturn. The bright, reddish planet will shine in the eastern evening sky this week, forming a triangle to the right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s bright stars Pollux and Castor. Mars will be highest due south at 9:30 pm local time and set in the northwest before sunrise. At 119 million km away and receding every night, Mars is still close enough to Earth to show us its bright polar cap and dark patches on its small rusty globe when viewed through a good backyard telescope.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, February 19, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting. The speaker will be Aiden Weatherbee, a space engineering student at York University. His topic will be The Shock of Discovery: JWST, Exoplanet Science, and AICO. Check here for details and watch the presentation at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

On Sunday afternoon, February 23 from 12:30 to 1 pm EST, astronomers from the David Dunlap Observatory will present some online DDO Sunday Sungazing. Registrants will learn how the sun works how it affects our home planet, and see views of the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting. More information and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!