The Sun Starts to Sport Spots, the Full Pink Moon is Sort of Super, and Planets Pair up at Dusk and Dawn!

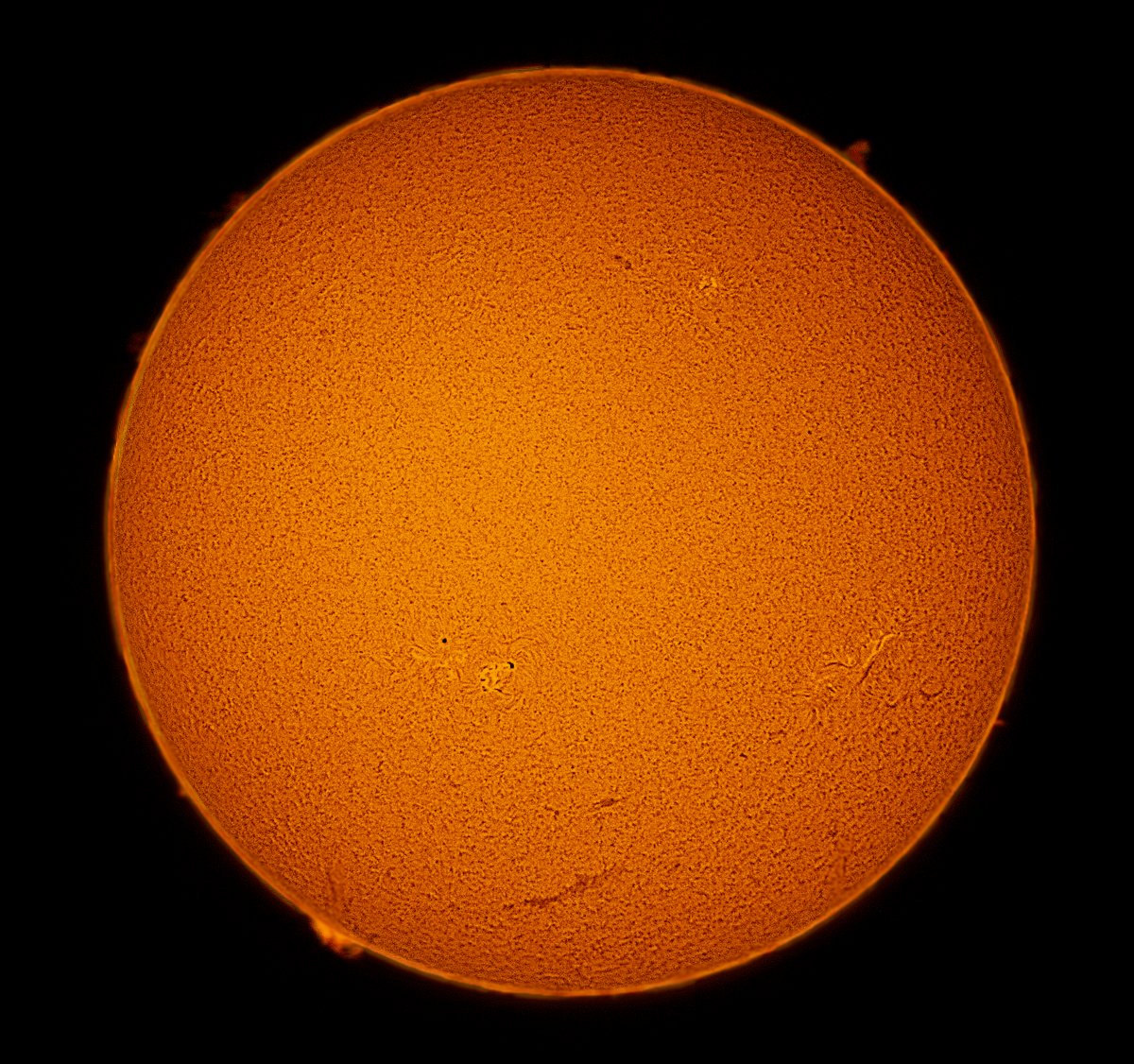

This full disk image of the sun on April 23, 2021 was taken by Dave Hoskins. This view shows the sun through a special solar telescope that uses the Hydrogen-alpha wavelength in the red part of the visible spectrum. A large group of small sunspots sits just to the lower left of centre, surrounded by brighter regions called plages. The dark slashes are prominences, strips of plasma that have been suspended over the sun’s surface, making them cooler and darker. The features extending into space around the edge of the sun are more prominences seen in profile.

Hello, Spring Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of April 25th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics.You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The sun is showing new activity after several lean years! The Full Pink Supermoon will arrive on Monday night worldwide. Then it will gradually leave the evening sky so galaxy chasers can resume looking at week’s end. Also in evening, reddish Mars passes a star cluster while between Procyon and Capella, and bright Venus and fainter Mercury will continue to ascend the post-sunset western sky! Jupiter and Saturn will be spectacular in the eastern pre-dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Sun Awakens

After several years of unimpressive quiescence the sun has begun to wake up! The intense fusion reactions inside the sun and the flow of ionized particles (mainly Hydrogen atoms split into their components of one proton and one electron) combine to give the sun an intense magnetic field. Since the sun is a sphere of compressed gases, and not a solid ball like Earth, its rotation is differential. A point on the sun’s equator will circle the star once in 24.47 Earth days, but a point close to its northern or southern pole will take almost 38 days! It’s interesting that the sun’s average rotation period of 28 days so closely matches our moon’s orbital period! But that’s a mere coincidence of nature.

The differential rotation of the sun causes the sun’s global magnetic field to wind up tighter over time. Magnetic fields can’t merge or cross one another. (That’s why it’s difficult to push the same poles of two magnets together.) As the sun’s field tightens up, small regions within it develop tangles of magnetism that prevent the heat beneath them from flowing out of the sun. Those cooler areas are visible from Earth as sunspots.

Sunspots can develop, grow, and fade in hours and days, or persist for weeks. Viewed from Earth, they take about two weeks to cross the sun’s disk – allowing us time to view the changes. We have also placed satellites on the far side of the sun to watch the solar hemisphere that we can’t see. That’s because, from time to time, the buildup of energy in those tangles gets violently released as solar flares, and as eruptions of matter into space called coronal mass ejections. Those events happen in minutes. It’s the latter that cause the auroras at Earth’s polar regions to grow stronger and they also endanger orbiting astronauts and satellites with intense radiation – if Earth happens to be in the line of fire. The flares vary in intensity. They are ranked by class, from weak A-class to extreme M- and X-class. During a flare, the magnetic field lines are snapping and re-connecting into simpler configurations.

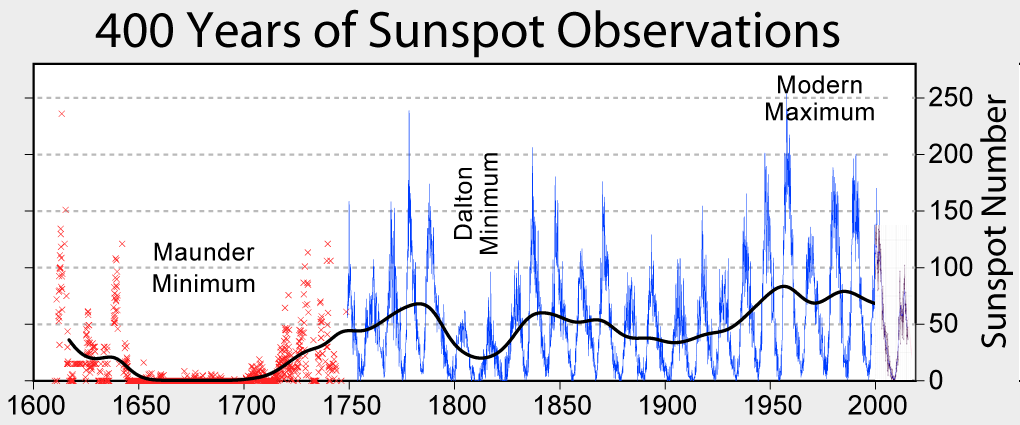

For a period of time, more and more spots appear, and more and more violent events occur. Eventually, the sun sheds its excess energy, the magnetic fields smooth out, and the sun settles into a quiet period with no, or very few, sunspots and flares. Over the years, astronomers have been able to view the sun through filters, count the sunspots, and record their number in a log. It turns out that the sun needs about 11 Earth-years to build up and then wind down. Even more interestingly, the polarity of the magnetic field reverses with each sunspot cycle, producing a 22-year period between true cycles.

There are lots of online sources showing graphs of the counts, including this page of recent ones and this one.

The round disk of the sun we see (through proper filters) is not the sun’s surface. Instead, it’s the radius where the gases cease to be opaque to visible light. (I like the analogy of the visible edge of a cumulus cloud in the sky. An airplane can still fly through the cloud.) This “visual surface” of the sun is called the photosphere. There, the temperature is about 5,500 degrees Celsius, or 5,777 K. That’s hot – but cool enough for non-ionized Hydrogen to survive – temporarily.

When a positively ionized Hydrogen nucleus grabs a passing electron, the atom settles down and emits a photon with a wavelength of 656.3 nanometres. That’s in the red part of the visible spectrum. Astronomers call that light HII (“H-two”) or Hydrogen-alpha light. Solar telescopes are designed to throw away all the other colours in the sun’s bright white light and pass only the H-alpha band to the eyepiece or camera.

The sun has been almost completely blank for much of the last three years. People with solar filters for their telescopes were disappointed. Fortunately, the sun still sported occasional solar prominences that were visible in H-alpha telescopes. Prominences are elongated, narrow zones where the local magnetic field is enhanced just enough to lift some plasma off the sun and suspend it – allowing it to cool a little. Prominences look like darkened, curved lines when they’re on the sun’s disk – and as fuzz, flags, trees, pyramids and other shapes when on the sun’s edge and seen in cross-section. Some people call them flares – but they aren’t. Prominences last a long time, and only change shape on a timescale of hours.

It looks like the new solar cycle is firmly underway! Already, small sunspots have been present on the sun during nearly two-thirds of the days of 2021 – so we have several years of great solar viewing to look forward to. When the spots are large enough, they are visible through eclipse viewers without a telescope! Remember to never look at the sun without using proper solar filters on your eyes and your binoculars or telescopes! Your eyes do not have pain receptors, and will not warn you that they are being permanently damaged. In a future post, I’ll share some tips for safe sun viewing.

If you’ve obtained eclipse glasses at a public sun session, a science shop, or in an astronomy magazine, dig them up and keep them handy. Yesterday, I checked Spaceweather.com to see if any spots were present on such a sunny day – and there were! The group I saw will be visible for several more days, and they’ve changed since yesterday! Mark your calendars – you can use those viewers for the partial solar eclipse visible after sunrise on June 10th!

The Moon

Although the moon will be very bright in the late evening sky worldwide this week, it will largely be out of the picture before the coming weekend – allowing us to resume our hunt for spring galaxies.

Tonight (Sunday) the 98%-illuminated, waxing gibbous moon will rise at about 7 pm local time and shine brightly among the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) – just a palm’s width above her brightest star, Spica.

The moon will officially reach its full phase at 11:31 pm EDT on Monday, April 26. That corresponds to 3:31 GMT on Tuesday, April 27. Because it is opposite the sun when full, the moon always rises around sunset and sets around sunrise. The April full moon always shines in or near the stars of Virgo (the Maiden), which is half the sky away from the sun’s current location among the stars of Pisces (the Fishes). I wrote about features to look for on full moon’s here.

This full moon will occur less than 12 hours before perigee, the point in the moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth, generating large tides worldwide and making this the second of four consecutive supermoons in 2021. The term supermoon was coined by an astrologer named Richard Nolle in 1979. He defined it to be a full moon that occurs when the moon is within 90% of its minimum distance from Earth. The term is not officially recognized by astronomers because supermoons are not all that “super” to us. Beyond being somewhat brighter and 7% larger than an average full moon, there are no unusual effects – and most people wouldn’t realize one is happening if the media didn’t promote it.

Don’t forget that even a supermoon can easily be covered by your pinky fingernail held up at arm’s length! By the way, a syzygy is the astronomical term for an alignment of three celestial objects – in this case, the sun, Earth, and moon. So this moon will be a lunar perigee syzygy. The May full moon will be the largest of 2021. It will be followed two weeks later by an apogee “mini” new-moon and annular solar eclipse on June 10.

Every culture around the world has developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names. The indigenous Ojibwe groups of the Great Lakes region call the April full moon Iskigamizige-giizis “Maple Sap Boiling Moon” or Namebine-giizis, the “Sucker Moon”. For them it signifies a time to learn cleansing and healing ways. The Cree of North America call it Niskipisim, the “the Goose Moon” – the time when the geese return with spring. For the Mi’kmaw people of Eastern Canada, this is Penatmuiku’s, the Birds Laying Eggs Time moon. The Cherokee call it Kawonuhi, the “the Flower Moon”, when the plants bloom. For Europeans, it is commonly called the Pink Moon, Sprouting Grass Moon, Egg Moon, or Fish Moon – terms that reflect the changes in the natural environment at this time of year. It seems that “pink” refers to the phlox flowers that bloom first during spring in eastern forests – and NOT to the way the moon will look!

From Tuesday onward the bright moon will wane in phase and rise about 80 minutes later each night. While doing so, it will travel east through Libra (the Scales), Scorpius (the Scorpion), the overlooked Zodiac constellation of southern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), and the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). In the closing days of this week, you can find the moon’s orb sitting low in the southern daytime sky after sunrise, like the ghost of night. Next week the moon will visit Jupiter and Saturn.

The Planets

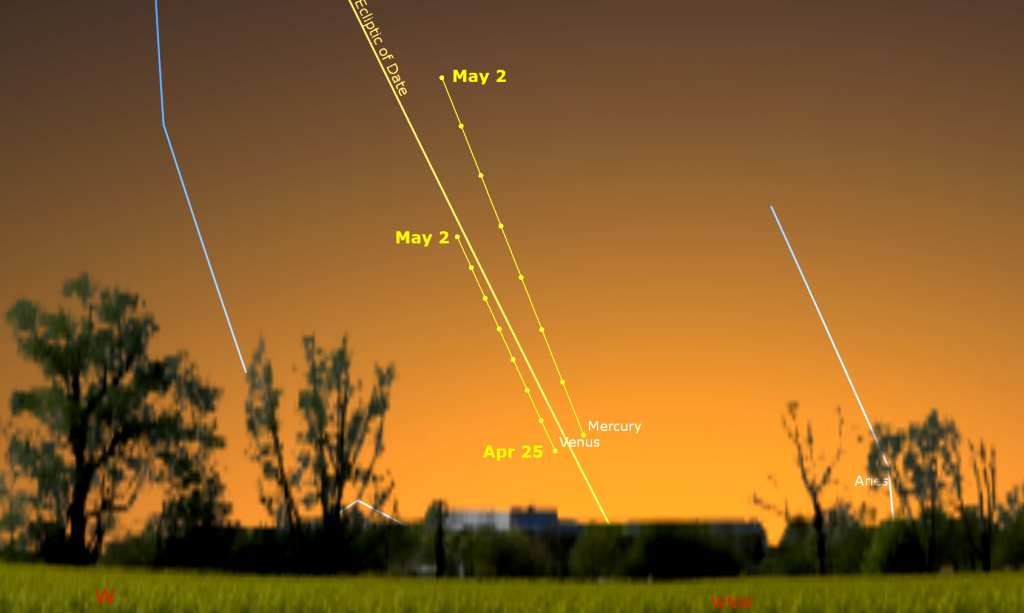

The post-sunset appearance of the inner planets Venus and Mercury that began last week will continue into early May.

Once the sun has completely disappeared below the west-northwestern horizon (after about 8:15 pm in your local time zone) search just above the horizon for the bright speck of Venus. (You will need a completely cloud-free vista without other obstructions like trees and buildings.) Tonight (Sunday) much fainter Mercury will be positioned about a thumb’s width to Venus’ upper right (1.5° to the celestial northwest). On each subsequent night, Mercury will jump higher while Venus climbs more slowly – allowing both planets to become progressively easier to see. Observers living closer to the equator will see those two planets more easily since they’ll be higher up in a darker sky.

As the sky darkens more fully, look higher in the west for the reddish dot of Mars. It will be located above and between Orion (the Hunter) on the left (celestial south) and Taurus (the Bull) on the right (celestial north). A very bright yellowish star named Capella will be positioned about two fist diameters to Mars’ right (or 23° to the celestial northwest). The brighter white star Procyon will sit about as high in the sky, to Mars’ left (celestial southeast). Despite Mars being much farther from Earth now, your telescope will still show it has small, ruddy disk. Look early – Mars will be getting too low for telescope views by midnight, and it will set in the west before 1 am local time.

Make an effort to view Mars on Monday night when its eastward orbital motion will carry the planet closely past the prominent open star cluster Messier 35, also known as the Shoe-Buckle Cluster, in Gemini (the Twins). Mars will be close enough to Messier 35 to share the field of view of binoculars from April 21 to May 1. They’ll appear together in the eyepiece of a backyard telescope at low magnification from Sunday through Tuesday. (Note that your telescope may flip and/or invert the binoculars’ orientation shown here.) Messier 35’s proximity to the ecliptic leads it to have frequent encounters with the moon and planets.

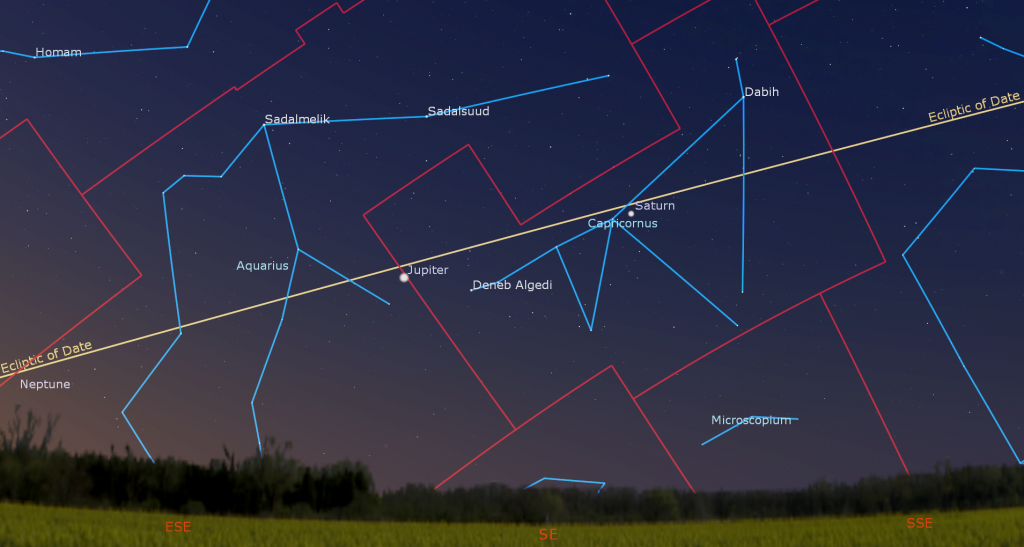

Saturn and Jupiter are continuing to shine in the southeastern pre-dawn sky this week. Yellow-tinted Saturn will rise with the stars of central Capricorn (the Sea-Goat) at about 3 am local time, and should be easily visible until almost 5:30 am. Much brighter and whiter Jupiter is positioned 1.5 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 15° to the celestial east). That separation will increase slightly every morning. The planet will rise at about 3:40 am local time and will be easy to see until almost sunrise.

Due to the very shallow angle of the morning ecliptic in springtime, Jupiter doesn’t get very high above the horizon before the dawn sky brightens, especially in mid-Northern latitudes. That makes it hard to obtain sharp views of the planet in a telescope. Since the ecliptic is more vertical for observers at southerly latitudes, both planets will be higher and clearer in telescopes there. If you are willing to get up early and take your backyard telescope outside, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible crossing Jupiter on Friday and next Sunday morning. Sunday’s GRS will be accompanied by the small black shadow of Jupiter’s moon Io between 4:22 am EDT and dawn.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday afternoon, April 27 at 3:30 pm EDT. We’re going to talk about seeing satellites, including the International Space Station. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

On Thursday, April 29 at 12 pm EDT, RASC National will continue their weekly, half-hour moon-observing series the Moon at Noon featuring Jenna Hinds and guests. Details are here and the registration link is here! Sessions are also livestreamed to YouTube here and can be watched at any time.

On Friday, April 30 at 10 am EDT, the Native Skywatchers group will present the next installment of their Two-Eyed Seeing: Art, Indigenous Astronomy, and NASA live streams. This one is Making Spirit, Making Art. They will present Ojibwe, Dakota/Lakota, and African/South African creations and star lore. More details are here.

Our in-person David Dunlap Observatory Saturday night events may be suspended at the moment, but we’re still pleased to offer alternatives – online programs! On Friday, April 30 at 7 pm EDT, tune in to DDO Astronomy Speakers Night – featuring a talk by the always-entertaining Professor Paul Delaney of York University. His topic will be Mars: The Next Chapter. More information and the registration link can be found here. A modest fee goes to support our ongoing efforts to deliver public programs at DDO.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!