The Waning Moon Leaves Evening, Gemini Ejects Meteors, Bright PM Planets, and Cassiopeia’s Best!

Geminids Meteors viewed from Chile, a four-hour composite imaged by Yuri Beletsky at Las Campanas Observatory in 2013. Orion is upside-down at left and the twin stars Castor and Pollux sit near bright Jupiter at centre. NASA APOD for December 8, 2019.

Hello, mid-December, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 11th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waning moon will vacate the evening sky this week, allowing us to enjoy the best features of Cassiopeia and the Pleiades star cluster. The best meteor shower of the year will peak, with some unwelcome moonlight, on Tuesday night. Meanwhile (almost) all of the planets are observable in evening. Read on for your Skylights!

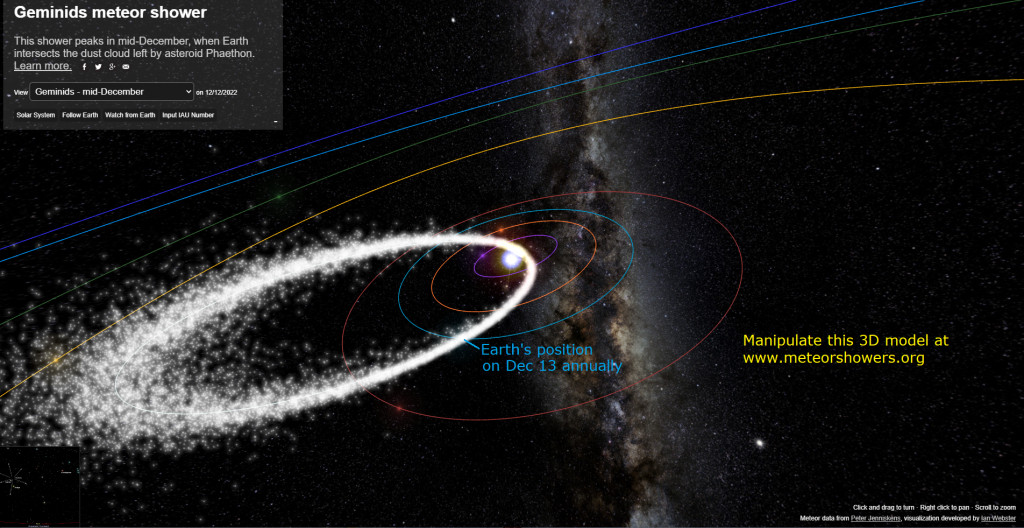

Geminids Meteor Shower

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through zones of debris left in interplanetary space by periodic comets (and, in some cases, asteroids). Over many, many years, the 1-2 gram particles that range in size from sand grains to small pebbles, accumulate and spread out into an elongated “cloud” along the comet’s orbit. (A good analogy is the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets quite dirty if the truck drives the same route many times!) If Earth’s orbit intersects the comet’s orbit, we experience a meteor shower. Showers repeat annually when Earth returns to the same location in space on the same date every year.

As we traverse the debris, Earth’s gravity attracts the particles, and they burn up as “shooting stars” while falling through Earth’s atmosphere. The particles zip through our atmosphere at speeds between 40,000 and 256,000 km/h. Each particle’s kinetic energy ionizes the air molecules it encounters, leaving a long trail of glowing gas that is less than a metre in diameter, but many kilometres long. Most trails occur in the thermosphere, the region of our atmosphere located about 80 to 120 km above the ground. Slower meteors need to reach the denser atmosphere at lower altitudes before they will form a trail. Viewed from the Earth’s surface, on a clear, dark night, we see the meteors glowing briefly as they streak across the sky – but those “shooting stars” have nothing at all to do with the distant stars of our galaxy.

The duration and intensity of any shower depends on the breadth of the particle cloud, whether we traverse it obliquely or straight-on, and whether we pass through the core or merely skirt its edge. The quality of the shower we see also depends on whether the moon is absent (yay!) or present and bright (boo!). For any given shower, the moon phase varies from one year to the next.

If you think of the Earth as a car speeding around the sun, the meteors are like bugs hitting its windshield. The constellation that our “car” is driving towards during the shower’s active period gives the shower its name. Meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but the members of a given shower will all appear to be traveling away from a particular location in the sky, called the radiant, that lies within a particular constellation. (This direction-of-travel rule can be broken when two showers are underway at the same time, and also by random meteors, called sporadics, which aren’t part of the main debris field, but instead are isolated particles drifting in interplanetary space.)

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, runs from November 19 to December 24 annually. The Geminids will deliver a peak number of meteors after midnight on Tuesday night, December 13, when up to 120 meteors per hour are possible under dark sky conditions. To be clear – that’s a maximum of two meteors per minute – and not the steady stream of them you might see in photos and videos on social media or on weather channels. Those are long exposure images. Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely coloured, and slower moving than average because they are produced by sand-sized grains dropped by an asteroid designated 3200 Phaethon. The shower will rapidly taper off during the following days.

The best time to watch for Geminids will be from full darkness on Tuesday until dawn on Wednesday morning. In 2022, the bright gibbous moon will rise in mid-evening, obscuring the fainter meteors. Try viewing them before 10 pm local time – or pick a spot where the bright moon can be hidden behind a tree or building. At about 2 am local time, the sky directly overhead, which will be positioned near the bright star Castor in Gemini (the Twins), will be plowing into the densest part of the debris field. True Geminids will travel away from that part of the sky, but don’t just watch that location – the meteors will be shortest there, and they can appear anywhere in the sky.

To see the most meteors (during any shower), find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from the city lights, and just watch the sky with your unaided eyes for a good long while. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors – their fields of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen because it’ll ruin your night vision. Keep your eyes to the skies, even while you are chatting with companions. I streamed an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session about meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

The media tends to promote meteor showers on their peak night – but Skylights readers know that showers are worth stepping outside for on the surrounding nights. I’d rather see fewer meteors on a clear night, than none at all on a cloudy peak night! (Do check the weather, though – as you can’t see meteors in cloudy skies.)

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when our natural night light will be rising late at night and lingering into the morning daytime sky, leaving the evening sky worldwide dark for stargazing.

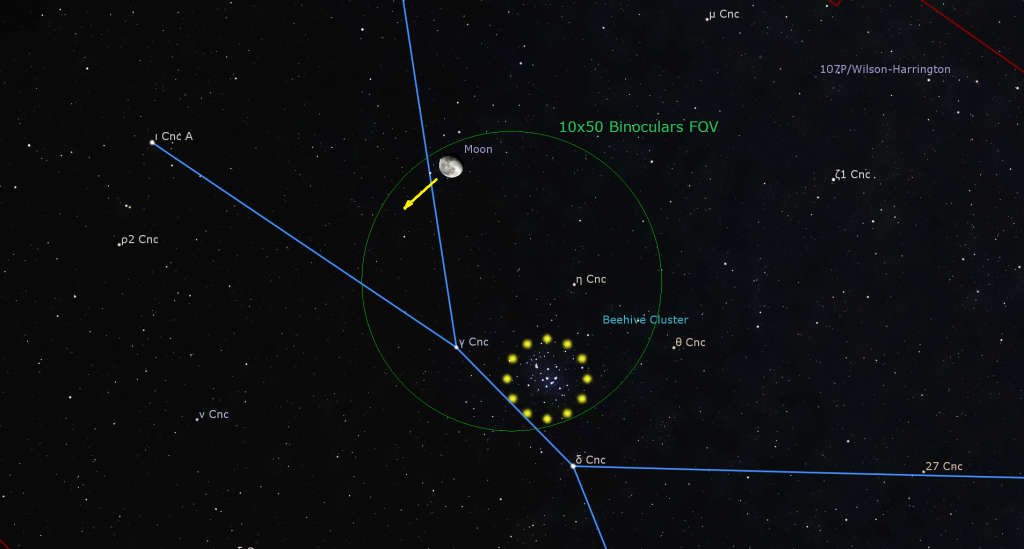

After the sky darkens tonight (Sunday), look northeast to see the bright, waning gibbous moon shining below the twin stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini. The moon will actually be among the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab) and a slim palm’s width above a large open star cluster known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. That’s close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Tuck the moon just beyond the top of your binoculars’ field of view to more easily see the “bees”, which will be spread across an area more than twice as wide as the moon. The moon’s easterly orbital motion will carry it closer to the cluster during the night. By dawn the rotation of the sky will also tilt the scene so that the cluster is to the moon’s lower left. The cluster is so large in the sky because it is relatively close to us – only about 600 light-years away.

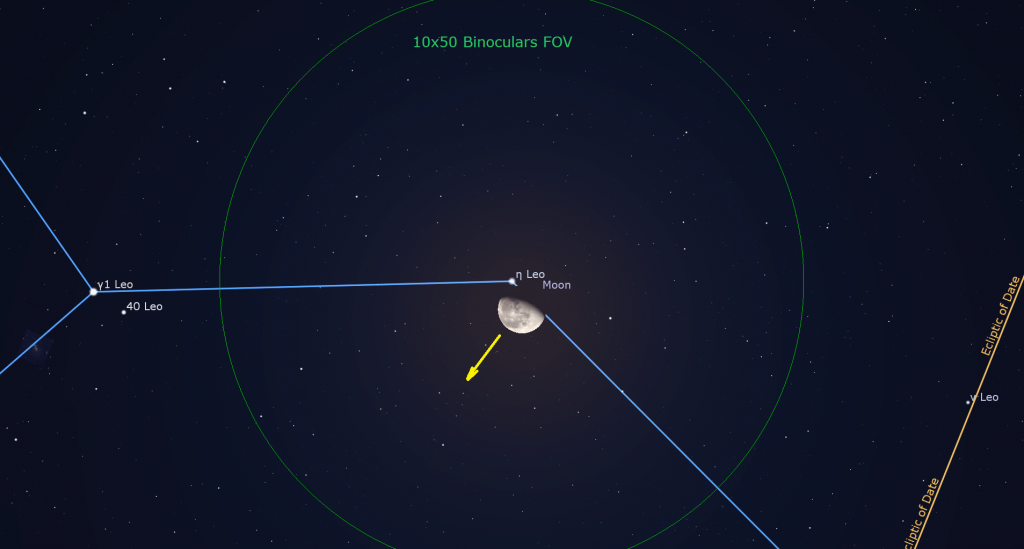

The moon will cross into next-door Leo (the Lion) on Monday night, and then spend Tuesday and Wednesday crossing its lengthy form. On Tuesday night, lucky observers located in a wide band from the Great Lakes region eastward to western Africa can watch the moon pass in front of, or occult the medium-bright star Eta Leonis, which marks the chest of the beast. In Toronto, the lit, leading edge of the moon will cover the star at 10:20 pm EST. The star will pop out from behind the moon’s dark limb at 10:47 pm EST. Binoculars or any sized telescope will show the event. Times vary by location so start watching before the times I indicated. A table of times for various places is here.

On Thursday night, the moon will venture into Virgo (the Maiden), another elongated constellation. The moon will reach its third quarter phase on Friday at 3:56 am EST, 12:56 am PST, or 08:56 Greenwich Mean Time. At third quarter, the moon is illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn sun. It will rise at about midnight local time, and then remain visible in the southern daytime sky all morning.

The moon will end this week shining as a lovely crescent in the southeastern sky before sunrise.

The Planets

Mercury and Venus will continue to lurk just above the southwestern horizon for half an hour after sunset this week, but only observers in the tropics will see them easily. Be sure to wait until the sun has completely disappeared before searching for them in binoculars. Those two inner planets will climb a little higher and set a little later with each passing day. Before those two inner planets set, all the planets will be above the horizon. Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn will form a 113 degrees-long arc across the sky, tracing out the plane of our solar system, with Uranus, Neptune, and a couple of major asteroids strung between them.

The increasingly earlier sunsets will allow the yellowish dot of Saturn to become visible in the southern sky after 5:30 pm local time. Enjoy your views of Saturn as soon as you can find it in your telescope because it will look less crisp as it drops lower through the evening. It’ll set at about 9 pm local time. Saturn will be shining just to the lower right (celestial west) of the medium-bright tail stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), Deneb Algedi on the left (celestial east) and Nashira on the right (celestial west). Over the next month, you’ll be able to use binoculars or your sharp eyesight to see Saturn’s easterly prograde motion shift the planet closer to them. I plotted Saturn’s long-term path here.

On a night with steady air, quality 10×42 binoculars (and larger) should show Saturn and its rings as a tiny oval. Even a small telescope can show the planet’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings. See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A). Any telescope should show that a segment of Saturn’s rings adjacent to the eastern limb of the planet is in shadow. That dark wedge gets a little smaller every night.

A small telescope can also pick up several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. (In contrast with Saturn, Jupiter’s axis is only tilted by 3°, so Jupiter’s moons show in a line running through that planet’s equator.)

Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper left (or celestial northeast) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to below (or celestial south) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Extremely bright, magnitude -2.5 planet Jupiter, which will shine 20 times brighter than Saturn, will become visible in the southeast shortly after 5 pm local time. Only half as bright Mars will come anywhere close to matching its brilliance. Jupiter will look best in a telescope when it climbs highest (or culminates) due south around 6:30 pm local time, and then it will set in the west by 1 am.

Your binoculars should be able to show you Jupiter as a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. The moons’ arrangement varies each night.

Once the sky is fully dark, use your binoculars to spy a pentagon-shaped ring of low-brightness stars shining about a fist’s diameter to the upper right of Jupiter. They make up the western head of Pisces (the Fishes). Above those stars, the Great Square of Pegasus (the Flying Horse) will be visible, even with your unaided eyes. It’s located about 2.5 fist diameters above Jupiter. The moonless nights will make seeing those stars easier this week.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Monday and Saturday, and late on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Sunday evening, December 11 the small shadow of Europa will cross the southern hemisphere of the planet from 7:50 pm to 10:12 pm EST. On Thursday, Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere from 7:45 pm EST to 10:10 pm EST. Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Saturday night from 8:05 pm to 10:10 pm EST. Europa’s shadow will cross again on Sunday, December 11 starting at 10:25 pm EST, a transit best seen in westerly time zones. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

In mid-evening this week, magnitude 7.9 Neptune will be located a palm’s width to the lower right (or 6° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter, about halfway to the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.3 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s). Try to view Neptune while it is highest, around 6:30 pm. Neptune is binoculars-close to several groups of medium-bright stars. I posted a finder chart for Neptune here. The large asteroids designated (4) Vesta and (3) Juno are currently travelling towards Jupiter across the knee stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

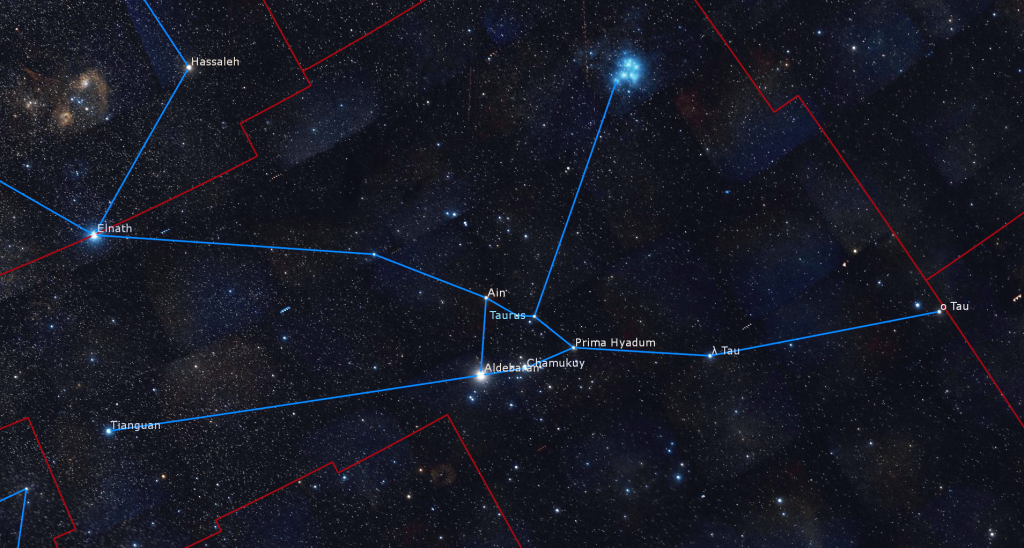

Mars officially reached opposition last Wednesday night, so it will be visible all night long. Once it clears the rooftops after dusk, its bright, magnitude -1.8 reddish dot can’t help but catch your eye. Mars will be positioned above and between Elnath, the bright northern horn star of Taurus (the Bull), and the even brighter reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the bull’s eye. Early risers can spot Mars above the western horizon before sunrise. Over the next month, Mars will steadily slide towards the bright Pleiades star cluster, which is the prominent little clump of stars above Aldebaran.

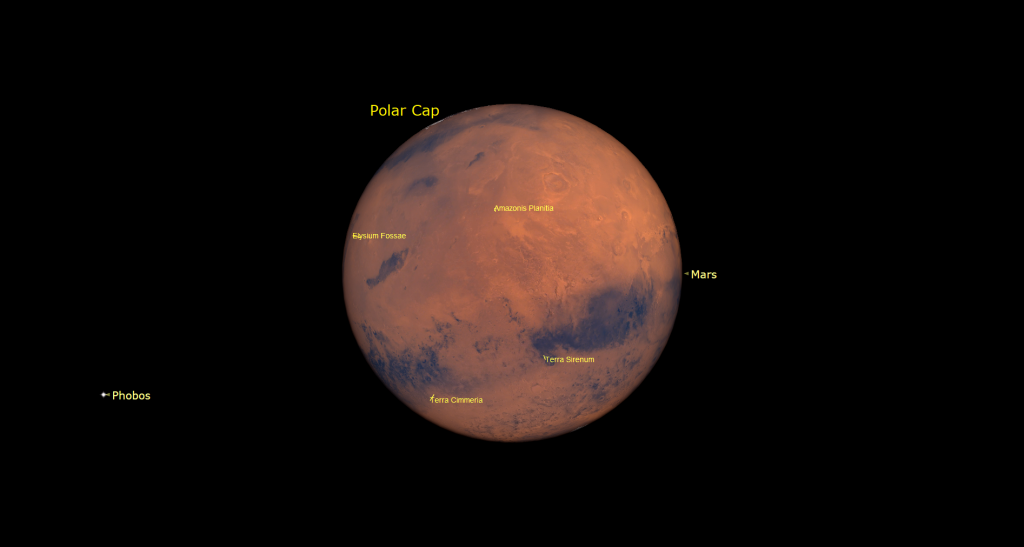

Mars will still be an impressive sight in backyard telescopes this week, showing an apparent disk diameter of 17 arc-seconds (Jupiter’s disk spans about 42 arc-seconds and the full moon is 1,800 arc-seconds wide). Mars’ Earth-facing hemisphere this week will display its bright northern polar cap – visible as a small bright spot along the planet’s edge, the dark Cimmeria Terra and Sirenum Terra regions, and the lighter-toned Amazonis Planitia and Eylsium regions. The polar cap might look larger or stretched out along Mars’ edge if you are viewing it through turbulent air or a mis-collimated telescope. Use my labelled image here, or you can use a terrific Mars mapping tool created by Ade Ashford at http://www.nightskies.net/skyguide/mars/mars.html. Use the drop-down menu to select from two views of Mars, labelled or not. Mars takes about 20 minutes longer than Earth to rotate once fully on its axis. So viewing the planet at the same time on subsequent nights will show roughly the same view of it, but with the surface markings shifted by about 5°. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view. If you find Mars is too bright, use a moon filter on it.

The distant blue-green planet Uranus is located about 40% of the way from Mars towards Jupiter, and about 1.4 fist widths to the upper right (or 14° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). Magnitude 5.6 Uranus will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the middle part of the eastern sky after dusk this week. It will climb to its highest point in the southern sky around 10 pm local time.

Appreciating the Pleiades

The beautiful open star cluster known as The Pleiades and the Seven Sisters is located in northwestern Taurus about one and a half fist widths above (or 13° to the celestial northwest of) the bull’s very bright, red star Aldebaran. The cluster is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects. Look for it climbing the eastern sky after dusk during December. It moves to its highest point in the southern sky in late evening.

The Pleiades is made up of the young, hot blue stars named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. And those stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades. (The Hyades cluster is the triangle of stars that make up the bull’s face.) Only six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – their parents, the stars Atlas and Pleione, are huddled together at the lower (east) end of the grouping.

Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster in a telescope. In 1610, he published a sketch made at the eyepiece. The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – reflected light from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. This proper motion will eventually carry the cluster to a position below Orion’s feet!

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have developed stories around this object. Many indigenous groups view the Pleiades as the doorway in to the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. In Japan, it is called Subaru, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

Cassiopeia: Andromeda’s Story in the Stars

The late fall and early winter evening sky features a group of easy-to-see constellations that are the characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – Princess Andromeda and the hero Perseus. If you missed the story, and my tour of Andromeda, I posted it here. This week’s moonless sky will be ideal for exploring the nearby constellation of Cassiopeia.

In Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was the queen of Aethiopia, married to King Cepheus, and mother to Andromeda. As a consequence of the events that led to Andromeda’s story, the queen and her husband were eventually banished to the stars, never resting as they circle the sky – and spending half of the time hanging upside down!

Cassiopeia is circumpolar – so close to the North Celestial Pole and therefore the North Star, Polaris that Canadians and other mid-latitude observers never see the constellation set. On early winter evenings, her distinctive, crooked “W” of five bright stars, each about four finger widths from the next, is situated high the northern sky (or just above the northern horizon, if you live closer to the equator) – ideal for viewing her treasures through the minimum amount of disturbing atmosphere.

If you face north after dusk, you’ll find Cassiopeia’s W is oriented upside-down, appearing more like a tilted “M” with its lower peak squashed. By 8 pm local time, the constellation will be more horizontal. Many world cultures have interpretations for this distinctive set of bright stars. A Cree story tells of a hunter named Ponoka who killed a great elk, shared the meat with his community, and then staked out the skin to dry it. Later, to honour the majestic beast, he threw the skin high into the sky. The constellation’s bright stars represent light beyond the skin shining through the stake-holes. The Inuit saw a blubber oil lamp and stand. The Navajo saw a female form that revolved around the pole. Pacific Islanders saw a great bird. Biblical scholars replaced the queen of Aethiopia with Bathsheba, Mary Magdalene, and others.

In western classical astronomical charts, Cassiopeia is depicted as sitting in a chair or throne while combing her hair, or looking into a mirror. The bright star at the left-hand (or western) tip of the constellation is named Caph (“the hand”). Also designated Beta Cassiopeiae, or β Cas, it is a yellow-white star located 54 light-years away from us. This aging star is beginning its transition to a red giant. (In his star atlas Uranometria, published in 1603, the German astronomer Johann Bayer assigned Greek letters to each constellation’s stars, ranked in descending order of brightness.)

The bright star located second from the left, and marking the higher point of the “M” is named Shedir or Shedar, Arabic for “breast”. Even though its Bayer designation is Alpha Cassiopeiae, or α Cas, its magnitude of 2.2 can be outshone occasionally by another of Cassiopeia’s stars (see below). Shedir is also an aging giant star. It is located 229 light-years away from us. Viewed in binoculars, you’ll see that Shedir is an orange-ish colour and it has a small companion sitting to its lower left.

The star that marks the queen’s waist in the middle of the constellation doesn’t have an Arabic name. Instead it is designated Gamma Cassiopeiae or γ Cas. It also has the unofficial nickname Navi, which is Apollo astronaut Gus Grissom’s middle name spelled backwards. This white star is located 549 light-years from us, and shines with a brightness that varies irregularly due to a high rate of spin and periodic gas ejection. At the moment, magnitude 2.15 Gamma is shining a little brighter than Shedir and Caph. In binoculars, look for a very orange or reddish star named HIP 3988 sitting a short distance below Navi.

Cassiopeia’s fourth star from the left, and the shallower point of the “M”, is named Ruchbah or Rukbat (“knee”). Bayer assigned it Delta (δ). Ruchbah is a whitish colour, eclipsing binary star located only 99 light-years away from us. It shines a little less bright when an orbiting dimmer companion star partially blocks its light every 25 months.

The last of the Cassiopeia’s five brightest stars is Epsilon Cassiopeiae or ε Cas. It marks the queen’s feet. Its proper name Segin, is of unknown origin. This modest looking, magnitude 3.35 star, is actually a blue-white giant located about 440 light-years away. It’s six times the mass of our Sun, but 2,500 times more luminous! This rapidly spinning star is shedding a ring of matter around it.

See if you can spot the medium-bright, magnitude 3.45 star between Shedir and Navi. That’s Achird, or Eta (η) Cassiopeiae, the queen’s mirror or comb – although some sources claim that the name means “girdle”. Achird is a yellow, sunlike star located only 19 light-years from Earth. On the opposite side of Shedir from Achird is dimmer Fulu, or Zeta Cassiopeiae, a hot, blue star located nearly 600 light-years away from us. The last named star in Cassiopeia is Marfak, or Theta Cassiopeiae. Marfak is located about four finger widths to the upper right (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial south) of Shedir. It’s a widely-spaced double star. Its companion can be spotted sitting just to its upper left.

The outer rim of our Milky Way galaxy passes directly through Cassiopeia, meaning that the area is rich in interesting objects and star fields. One of my favorite objects can be seen in binoculars or a backyard telescope. It’s an open star cluster designated NGC 457, but I prefer its common names – the Owl Cluster, ET Cluster, or Dragonfly Cluster. The cluster was discovered by William Herschel in 1787 and is positioned more than 7,900 light-years away from us! It consists of two prominent, brighter yellow stars that form the eyes. A sprinkling of dimmer stars forms the owl’s body and feet, and two curved chains of stars look like upswept wings.

Be aware that the critter is positioned with its head pointing away from Cassiopeia. This will be the case in binoculars, but your telescope will flip the image. Locate the owl by taking Navi and Ruchbah and making them the two vertices of a right-angle triangle. The cluster sits at the third vertex, where the 90 degree corner is. It’s about four finger widths above Ruchbah – as if the queen is bouncing a baby owl on her knee!

Sweep your binoculars a few finger widths to Caph’s upper left and look for a dense knot of faint stars named Caroline’s Rose (NGC 7789). Another bright star cluster named NGC 129 sits between Caph and Navi. Located outside of the border of Cassiopeia, a generous palm’s width to the upper right of Ruchbah, you’ll find the spectacular and very bright Double Cluster. It is visible with unaided eyes, and really pops in binoculars.

Owners of large telescope can look for the large nebulas that reside in Cassiopeia. Extending a line from Shedar to Caph by a distance equal to their separation brings you to the small, bright Bubble Nebula (NGC 7635) and the Salt-and-Pepper Cluster (NGC 7654). Search a thumb’s width to the right of Shedar for the Pacman Nebula, a pink cloud of hydrogen gas with a certain distinctive shape. About a palm’s width to the right of the star Segin, near the far right of the constellation’s official boundary, are the spectacular Heart Nebula and Soul Nebula. Although they will both fit into one binoculars field of view, they are very faint, and are best captured in long exposure photographs. Perhaps they are the slippers the queen has kicked off! If there are astronomers on a planet around our nearest star, Rigel Kentaurus (aka Alpha Centauri), they will see our sun as a yellow star situated in the space between the Heart and the Soul!

While you’re gazing at the queen’s treasures, use the left half of Cassiopeia as an arrowhead that points directly towards the great Andromeda Galaxy. The galaxy is approximately 1.5 fist widths from the tip of the arrow. At 2.5 million light years away, its faint smudge is among the farthest objects visible to unaided human eyes. Under dark skies, you might be able to detect it as a glowing patch that spans more than two finger widths across, or several full moon diameters. In actuality, it measures six moon diameters across and two moon diameters wide!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 17 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll select a fun topic in astronomy, and we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!