The Waning Moon’s Crescent Covers Leo’s Heart, Orionids Meteors Multiply, and Autumn Sights to See!

This long exposure image of the Triangulum Galaxy, also known as Messier 33 and NGC 598, was captured by Steve McKinney of Toronto in 2012. His photo covers a thumb’s width of the sky, but it has been rotated by 180 degrees from a binoculars view. Look for the 2.7 million light-years-distant galaxy climbing the eastern sky on October evenings.

Hello, Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 16th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

This week the moon will vacate the evening sky as it wanes past Monday’s third quarter phase – so we’ll focus on the Orionids meteor shower peak on Friday morning, the evening comet for telescopes in Corona Borealis, and some terrific dark sky evening targets for binoculars. The moon will pass in front of a bright star in Leo on Thursday morning. In the evening sky, Saturn will slow to a stop near the bikini’s belly button star, Mars will continue to visit the Crab Nebula, and spots will cross bright Jupiter. Read on for your Skylights!

Orionids Meteor Shower

We’ve entered meteor shower season! Over the next few months, Earth will experience several showers. My friend Blake Nancarrow created a very informative graph of meteor shower intensity throughout the year here, on his Lumpy Darkness blog.

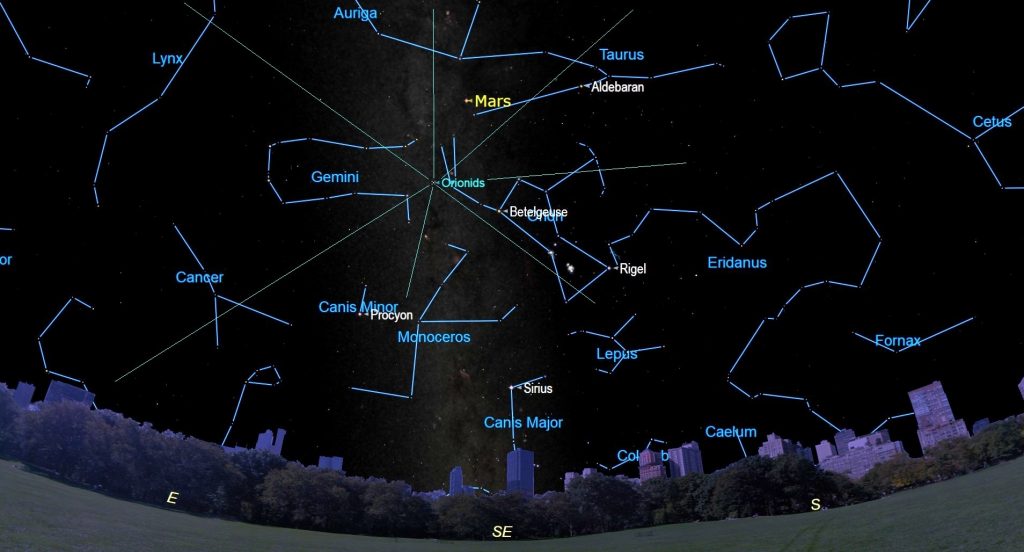

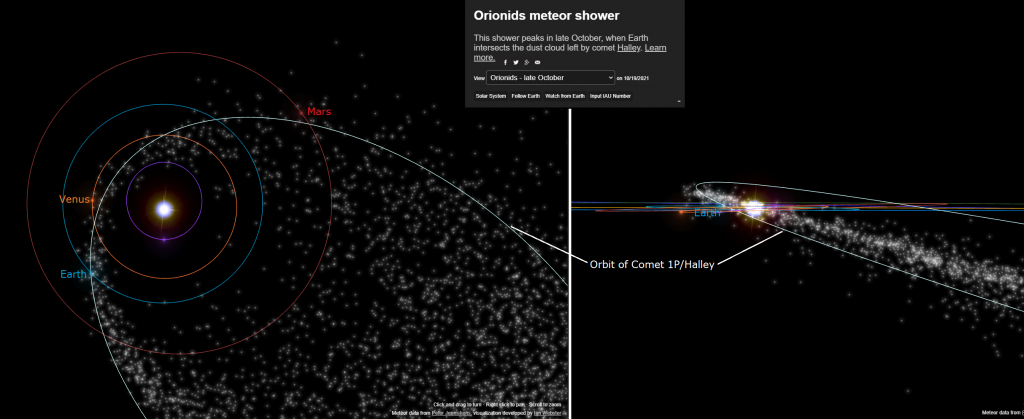

The excellent Orionids Meteor Shower, which is observable world-wide, happens every year between September 23 and November 27. That’s when Earth is plowing through a cloud of fine particles dropped by repeated past passages of the periodic comet designated 1P/Halley, or simply Halley’s Comet. The Orionids (for short) will peak in the hours before dawn (in your local time zone) next Friday, October 21. At that time, the sky overhead will be pointing toward the densest region of the particle field, generating as many as 10-20 meteors per hour. Although not especially numerous, Orionids are known for being bright and fast-moving.

The meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but true Orionids will seem to be travelling in a direction away from a location in the sky called the radiant that is near the bright red star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion – giving this shower its name. This year, bright, reddish Mars will shine nearby. The Orionids radiant will rise at about 10:30 pm – but up to half of the Orionids will be travelling downwards, and will therefore be blocked by your local horizon until Orion climbs higher. The most meteors will be seen before daybreak on Friday, when the radiant is highest in a dark sky. You will still see a reduced number of Orionids during Thursday evening and Friday night, and fewer yet on the surrounding nights. Fortunately, the moon will only be a 17%-illuminated crescent on the peak morning – and it won’t even rise until the wee hours, for those viewing Orionids in evening.

While the Orionids Shower will last until late November, the meteors will decrease in quantity every night after Friday’s peak. The Orionids has a broad period of activity because the orbit of Halley’s Comet is tilted by only 17° from the plane of the Solar System, and it also crosses Earth’s orbit obliquely. There’s a terrific, interactive, 3D meteor shower visualizing tool at https://www.meteorshowers.org/.

To see the most meteors, first check the weather forecast – you won’t see meteors if it’s cloudy. Get away from light-polluted, urban skies and find a dark site with plenty of open sky. If the moon is up, try to hide it behind a tree or building. Don’t bother using binoculars or a telescope for meteors – their fields of view are too narrow. Don’t focus your attention on the sky near the radiant because those meteors will be travelling towards you and will produce very short streaks. Instead, keep your eyes toward the sky overhead.

To preserve your eyes’ dark adaptation, avoid the bright white light from phones or tablets. Red light is fine – so cover your device’s screen with red film or use its red mode. If the peak night forecast calls for clouds, try the nights before or the nights after. Good luck!

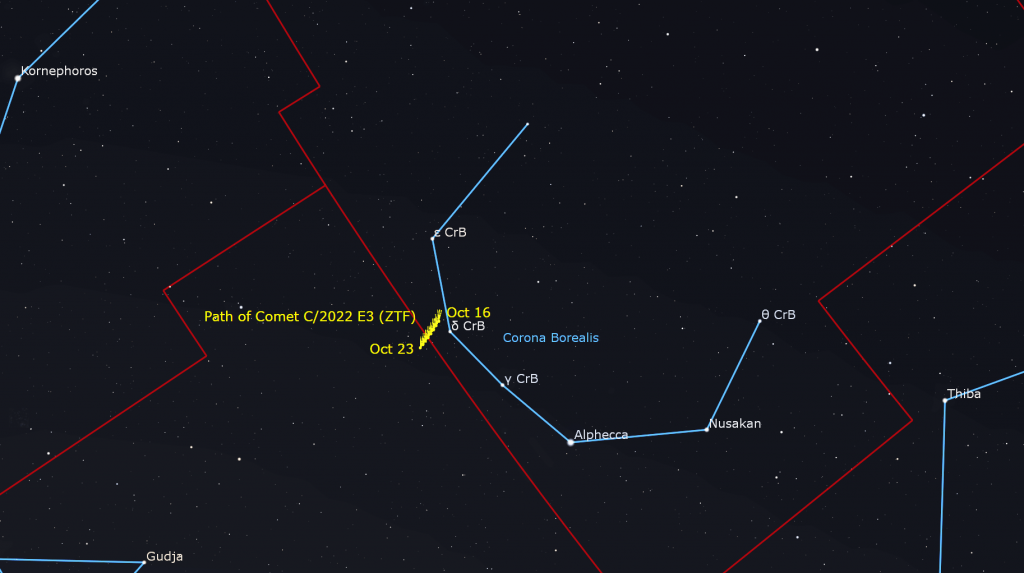

Comet E3 Update

On March 2, 2022, the widefield cameras of the Zwicky Transient Facility on Mount Palomar, California discovered a comet now named c/2022 E3 (ZTF). It is predicted to become bright enough to see in binoculars next February. For now, it is still very far away, but is visible in 8” or larger telescopes during evening. This week comet E3 ZTF will continue to travel slowly in the left-hand (or southeastern) part of the constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown). That constellation occupies the lower third of the western sky after dusk. The keystone shape of Hercules is positioned above it, and the very bright star Arcturus will sparkle below it.

Tonight (Sunday) the comet will sit just to the upper right of the medium-bright star Delta Coronae Borealis. By Wednesday it will shift to sit a half finger’s width to the left of that star. Next Sunday night it will be positioned just to the lower left (or celestial south) of Delta. The entire week it will be close enough for the comet and that star to share the view in a telescope.

The comet will remain near the boundary between Corona Borealis and Serpens (the Snake) for the next two months, but those stars will eventually be overwhelmed by the evening twilight – so make your attempts to see the comet sooner than later. In a telescope this week, expect the comet to appear as a small fuzzy patch of magnitude 11.4. Any tail it might have will point up, though your telescope may flip the view.

The Moon

This is the favorite week of the lunar month for astronomers. Earth’s natural satellite will be decreasing its angular separation from the sun, so it will only be shining in the post-midnight sky and waning in illuminated phase. That will provide night owls with increasingly darker skies worldwide. That later-rising moon will also linger into the morning daytime sky like the ghost of night.

After is rises around 11 pm local time tonight (Sunday), the half-illuminated moon will shine among the stars of Gemini (the Twins), forming a pretty triangle to the right (or celestial southwest) of the up-down pair of Gemini’s brightest stars, Castor and Pollux. During the night, the moon’s easterly orbital motion will carry it closer to Pollux (the lower, more easterly star), allowing all three objects to share the view in binoculars on Monday morning until dawn.

The moon will officially complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Monday at 1:15 pm EDT, 10:15 am PDT, or 17:15 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third quarter (or last quarter) phase the moon always appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. The observation that the lunar terminator, the boundary that separates the lit and dark hemispheres, becomes a straight line only at first and third quarter told ancient observers that the moon was a sphere. I pay close attention to the night-time weather forecasts for the week of nights following the third quarter.

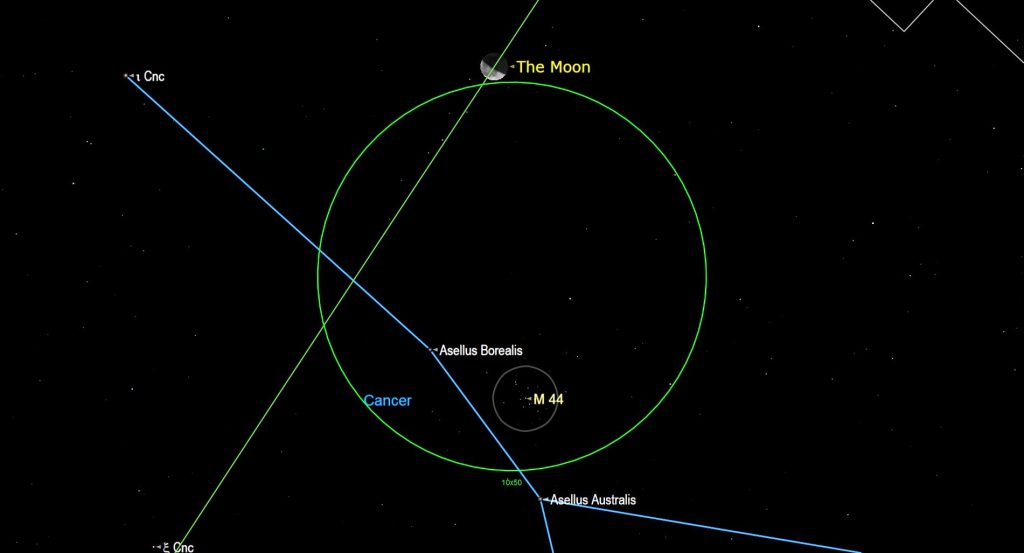

During the wee hours of Tuesday morning, the then waning crescent moon will be climbing the eastern sky above the faint stars of Cancer (the Crab). The moon’s easterly orbital motion will steadily carry it closer to central Cancer. Towards dawn, the moon will shine binoculars-close to Cancer’s large open star cluster, which is known as Messier 44, the Beehive Cluster, and Praesepe (the Manger). To see the cluster’s swarm of stars, which span more than twice the moon’s diameter, hide the moon just above your binoculars’ field of view. The centre of the “hive” is only a finger’s width north of the ecliptic – so the moon and the planets pass through it, or just close to it, very frequently.

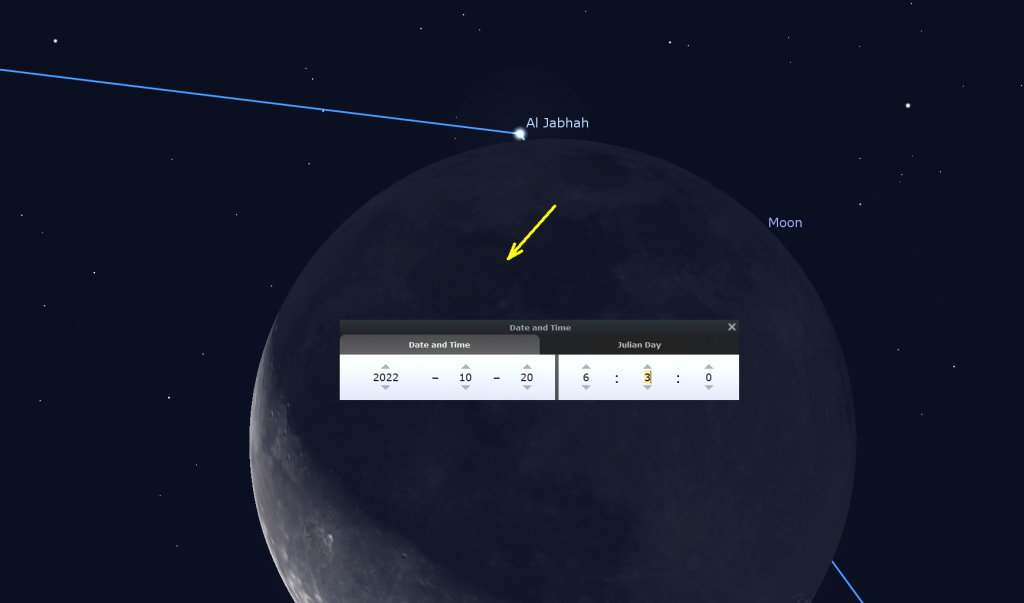

In the eastern sky on Thursday morning, observers across most of the continental USA and southern Canada can use binoculars and backyard telescopes to see the crescent moon pass in front of (or occult) the bright star Eta Leonis. That star marks the chest of Leo (the Lion). Exact timings will vary by location, so use an app to determine the precise times where you are. In the GTA, the event will occur in a bright morning sky. In Calgary, the bright, leading edge of the moon will cover Eta Leonis at 5:07 am MDT or 10:07 GMT. The star will emerge from behind the moon’s opposite, dark limb at 6:02 am MDT. For best results, start watching a few minutes ahead of each time noted.

The pretty moon will continue to prowl through the lion’s stars on Friday and Saturday morning. On Friday morning, look the dwarf planet designated (1) Ceres will be positioned several finger widths to the upper left (or 3 degrees to the celestial north) of the moon – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. With a magnitude of only 8.84, Ceres will be seen more easily in a backyard telescope. The somewhat brighter stars HIP 53881 and 52 Leonis shining on either side of Ceres can assist in your search. Though not really visible, the prominent galaxies M95, M96, and M105 will be positioned just to the upper right of the moon.

Watch for the very slim crescent moon, only 4%-illuminated, shining over the eastern horizon before sunrise on Sunday.

The Planets

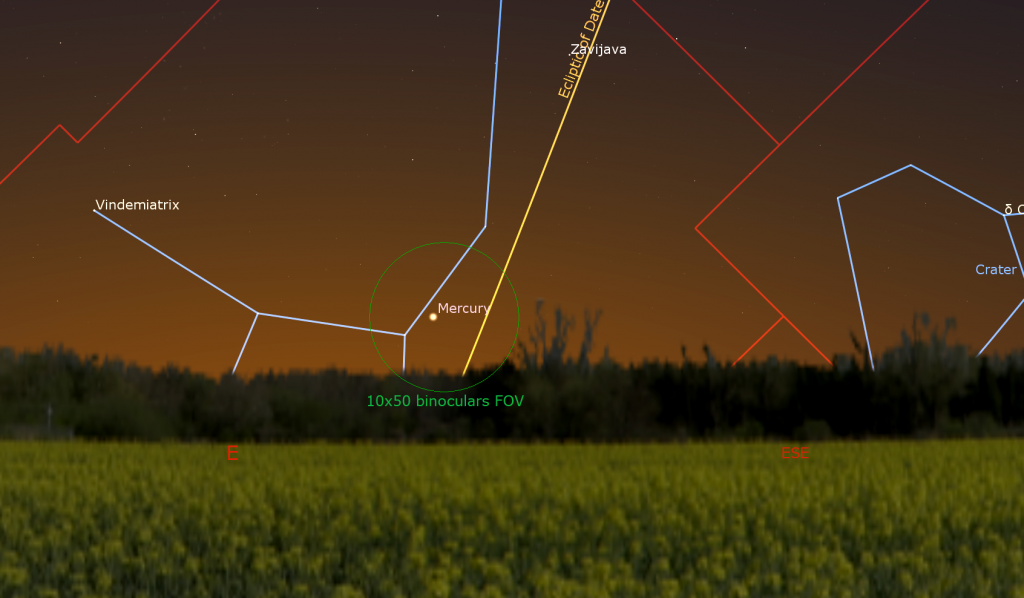

Of the two inner planets, only Mercury will be far enough from the sun to be seen this week. If you have a cloud-free eastern horizon before sunrise, look for the relatively bright, speedy planet shining very low in the sky in the minutes before 7 am local time, just as the surrounding stars of Virgo (the Maiden) fade out. Mercury is rapidly descending sunward every morning, so try to look for it early in the week. By next weekend, Mercury will be gone from view. Turn your optics away from the east before the sun rises. Meanwhile, bright Venus will be unobservable while it passes the sun in superior conjunction this week. (Superior conjunction means that Venus is nearest to the sun in the sky while orbiting on the far side of the sun from Earth. Inferior conjunctions happen when a planet passes between Earth and the sun.)

The rest of the planet-action starts in evening! Once Mars appears low over the east-northern horizon after 9:30 pm local time, all the remaining planets, and several bright asteroids, will become observable in binoculars and backyard telescopes.

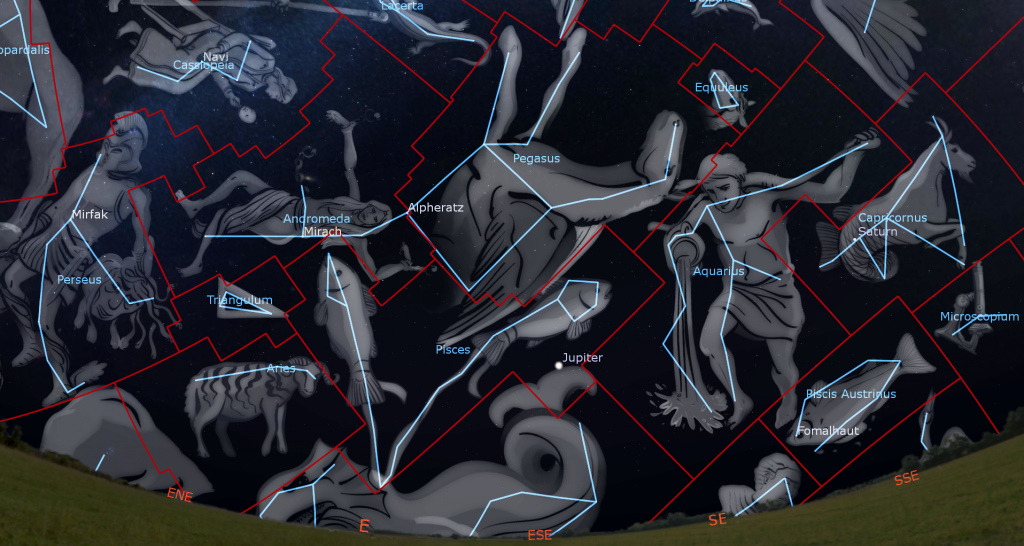

For those who just want to head outside and look up unaided, extremely bright Jupiter will grab your attention as it blazes away in the lower part of the southeastern sky even before the sky is fully dark. When the sky darkens a little more, cast your gaze about four fist diameters to the right of Jupiter, and a little higher, to see 24 times fainter, yellow Saturn. Saturn will remain in view above the trees until after 1 am local time, while Jupiter will follow it down before dawn. Mars won’t clear the trees until after 11 pm. Then it will cross the sky all night long.

Any decent pair of binoculars will show Jupiter as a small disk flanked by its string of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are occulting one another. Their arrangement varies each night. Very good binoculars will show Saturn and its rings as an oval. Mars will look like a red speck – for now.

A ring of faintish stars sits about a fist’s diameter above Jupiter. They form the western head of Pisces (the Fishes). The entire ring should almost fit within your binoculars’ field of view. The brightest two stars are on the left and right. The stars in the ring shine at about the magnitude limit that you can see without aid under suburban skies. How many can you see? The rest of Pisces forms a huge V of faint stars to Jupiter’s left (or celestial east).

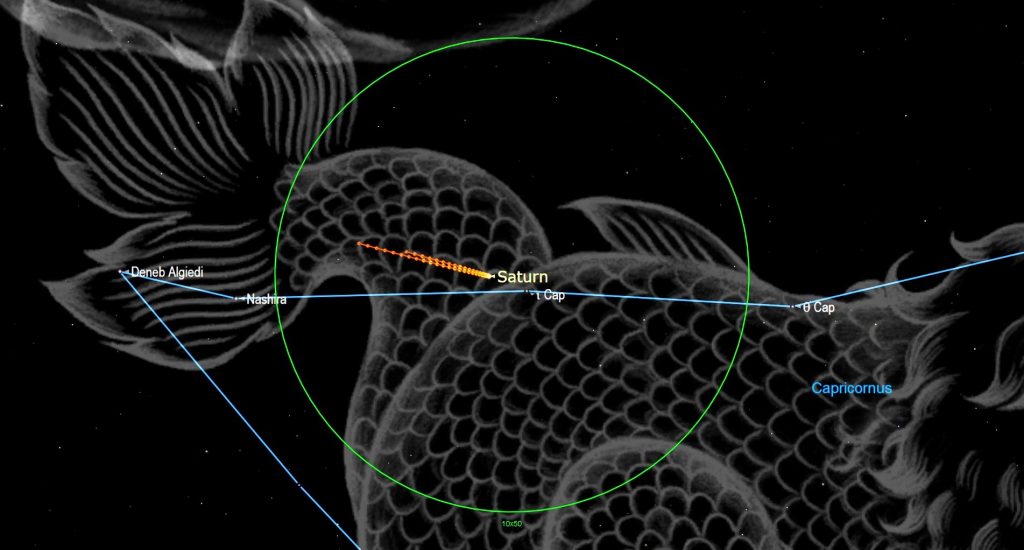

On Saturday night, Saturn’s westerly motion through the stars of central Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will slow to a stop as it completes a retrograde loop that it began in early June. On Saturday, Saturn’s magnitude 0.6, yellowish dot will shines less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.6 degrees to the celestial northeast) of the medium-bright star named Iota Capricorni. That’s close enough to share the view in a backyard telescope. When Saturn resumes its regular easterly prograde motion in the coming weeks, it will widen its separation east of that star. To my eyes, Capricornus resembles the bottoms of a bikini. Saturn is just to the left of the belly button.

Planets look clearest in telescopes when they are higher in the sky. At that time, you are not viewing them through as much intervening, turbulent air. This week, Saturn will be highest in the south around 9 pm local time, Jupiter will culminate around midnight, and Mars will climb highest at 5 am. Those times shift earlier by half an hour each week. Feel free to view them any time. The times are above are just the absolute best. Let’s look at what a telescope can show you.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings, which are sufficiently edge-on to us to allow Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond the ring plane. See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark zone that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A). Saturn’s position west of the anti-solar point has caused the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. Where you see that shadow will depend upon how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it’s toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be toward lower right. An equatorial mount will rotate the scene, too. To best see Saturn’s features, take long looks and wait for moments of perfect clarity.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower right (or celestial southwest) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to above (or celestial north of) the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth-hours, anyone can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pink, pale Great Red Spot crossing the planet for 3 hours on every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Tuesday and Thursday, late on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday evening, and during the wee hours of Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the GRS with them.

The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. For observers in the America’s, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Sunday night, October 16 between 10:10 pm and 12:20 am EDT. On Sunday morning, October 23 between 2:40 am and 5 am EDT, the small, black shadow of Europa will cross the southern half of Jupiter’s disk. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone. On Wednesday evening, October 19, sky-watchers across Africa, Europe, and Asia can see a rare treat when two shadows cross the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, together with the Great Red Spot between 17:20 GMT and 19:00 GMT.

This week, Mars will show a waxing 91%-illuminated disk, with hints of the dark markings that will sharpen up as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to the red planet over the coming months. We’re 104 million km (or 5.7 light-minutes) away from it this week. Watch for the bright reddish star Aldebaran twinkling 1.5 fist widths to Mars’ upper right (or celestial southwest) and bright yellow star Capella shining 2.3 fists to Mars’ upper left (or celestial north).

The easterly motion of Mars has been carrying it closely past the Crab Nebula, otherwise known as Messier 1 and NGC 1952, in Taurus. Tonight (Sunday) Mars will sit a finger’s width to the upper left (or 1 degree to the celestial north) of the nebula – easily close enough to share the view in a backyard telescope. for the rest of this week, Mars will shift more to the nebula’s left (or northeast). The relatively faint and fuzzy oval of the Crab Nebula is best viewed in larger telescopes under dark skies – and while it is higher in the sky during the wee hours. The waning moon’s light will stop interfering with our views from Tuesday onwards.

There are several fainter planets and asteroids lurking between the bright ones.

The main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta and the blue planet Neptune are within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes in a dark sky. Magnitude 6.8 Vesta is located 0.9 fist diameters to the lower left of Saturn, and a palm’s width from the two medium-bright stars Yen (aka Zeta Capricorni) and Deneb Algedi (aka Delta Capricorni). They mark the left-hand, eastern side of the bikini bottom. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is located 0.8 fist widths to the right (or 8° to the celestial south-southwest) of Jupiter, which will slide a wee bit closer to the distant planet every night. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.4 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s.) Try for Vesta and Neptune while they are highest – in late evening. I recently posted finder charts for them here.

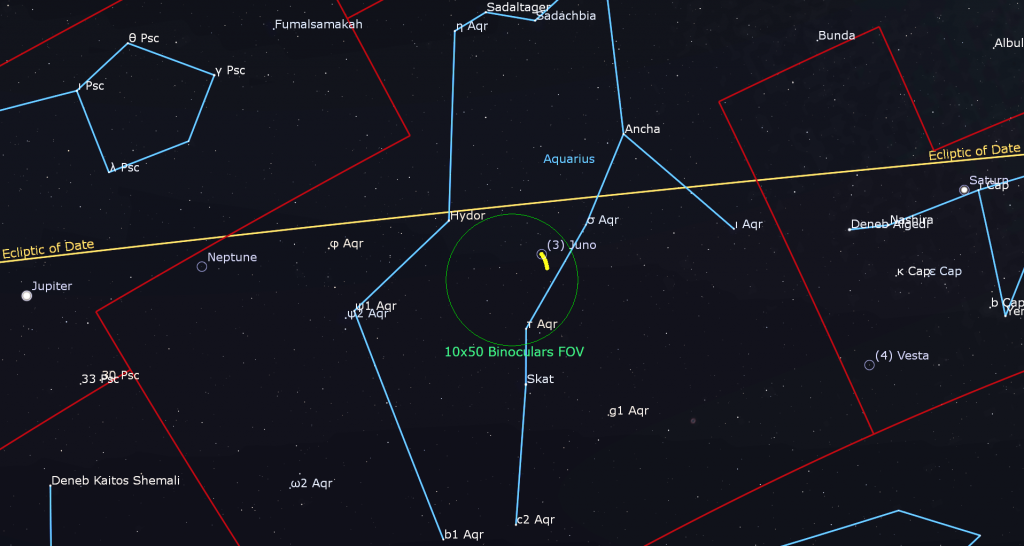

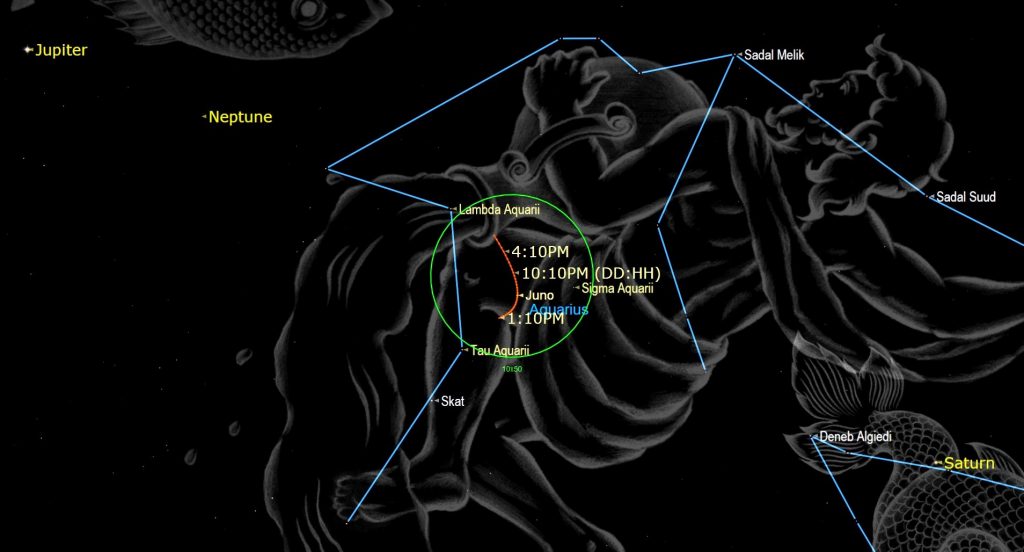

The main belt asteroid designated (3) Juno is about midway between Saturn and Jupiter. On Tuesday, October 18, its westward motion will slow to a stop as it completes a retrograde loop that it began in late July. After that night it will resume eastward prograde motion through the stars of central Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The magnitude 8.6 minor planet can be spotted in binoculars and any telescope within a triangle formed by the medium-bright stars Lambda, Tau, and Sigma Aquarii.

Uranus is located between Mars and Jupiter, and about 1.3 fist widths to the upper right (or 13° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). The magnitude 5.7 planet will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by 10 pm local time this week.

Dark Nights Delights

The moonless evenings this week will be ideal for stargazing. Last October, I posted a detailed tour of the constellation Pegasus (the Flying Horse). You can read it here.

Here are some suggestions for additional deep sky objects that are bright enough to see in binoculars this week, even in mildly light-polluted skies.

In mid-evening during mid-October, the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) is positioned halfway up the east-northeastern sky. This constellation’s location straddling the outer reaches of the Milky Way has filled it with rich star clusters. The largest of these clusters, named Melotte 20, surrounds Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak, or Alpha Persei. Also known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group and the Perseus OB3 Association, the cluster is a collection of about 100 young, massive, hot B and A-class stars spanning 3 degrees (or six full moon diameters) of the sky. The cluster can be seen with unaided eyes, and improves in binoculars. It is approximately 600 light years from the sun and is moving through the galaxy as a group. Mirfak is moving with them. That elderly, yellow supergiant star has evolved out of its blue-coloured phase and is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen in its core.

The northwestern region of Perseus contains the well-known Double Cluster. Two bright, open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and only 0.45 degrees apart, form a spectacular sight covering a single finger’s width of sky. If you face northeast, they will be located midway between W-shaped Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the bright star Mirfak below it.

You can try to see the pair of clusters with your unaided eyes. They’ll look like two fuzzy patches. Or, use binoculars or a low power, widefield telescope to view them in all their glory. The lower, more westerly cluster is also known as NGC 869. It is more compact and contains more than 200 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the higher, easterly cluster, is slightly more spread out. Both clusters reside in the Perseus Arm of our Milky Way galaxy and are located about 7,300 light-years from the sun. Their region of the sky is heavily loaded with opaque interstellar dust that has extinguished their intensity.

An extra-galactic treat is located nearby. After dusk on October evenings, the Andromeda Galaxy is halfway up the eastern sky. This large spiral galaxy, also designated Messier 31 (or M31), lies a whopping 2.5 million light years from us, and subtends an area of sky measuring 3 by 1 degrees (or six full moon diameters across and two diameters high). Under dark skies, the galaxy can be seen with unaided eyes as a faint smudge to the left (or celestial northeast) of the square of Pegasus (the Horse). The three highest (or celestial westernmost) stars of Cassiopeia, Caph, Shedar, and Navi, conveniently form an arrowhead that points towards the Andromeda Galaxy. Binoculars will reveal the galaxy better. In a telescope, use low magnification and look for the two fainter, small companion galaxies. Messier 32 is close to M31’s core. Twice as large Messier 110 is farther from M31’s core, on the opposite side.

If your sky is very dark, aim your binoculars 1.5 fist diameters below (or 15° to the celestial southeast of) M31 to see the faint, but large, fuzzy oval of Messier 33, the Triangulum Galaxy. It measures about two moon widths left-right by 1.5 moon widths tall. At 2.7 million light-years away, it is the farthest thing human eyeballs can see without assistance. For the 2022 General Assembly of the Royal Astronomical society of Canada, I delivered a fun, short talk called Science Fiction in the Stars. I mention the connections between those two big autumn galaxies, Star Wars, and E.T. The Extra-terrestrial. Here’s the link!

Later in the evening, you can look for the bright little star cluster known as the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, and Subaru (in Japan). It will rise over the east-northeastern horizon by about 7:30 pm local time.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 19 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Jabavu “Jaba” Adams of York University. His talk is titled “Always looking, always learning – from amateur astronomy to computing, and back again”, how amateur stargazers can use information tools and maker space techniques. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, October 25 at 3:30 pm EDT. Recently, the team behind Stellarium has made major improvements to the mobile app version of the software, making it comparable to the gold standard SkySafari app. We’ll work through the basic functions and the advanced features available in Stellarium Plus, including Satellite tracking, telescope/eyepiece simulated views, and observing planning. We’ll highlight some news for Stellarium desktop users, too. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!