The Waxing Moon’s Worth Watching, Venus Cuddles Mars, and Bright Sights for Moonlit Nights!

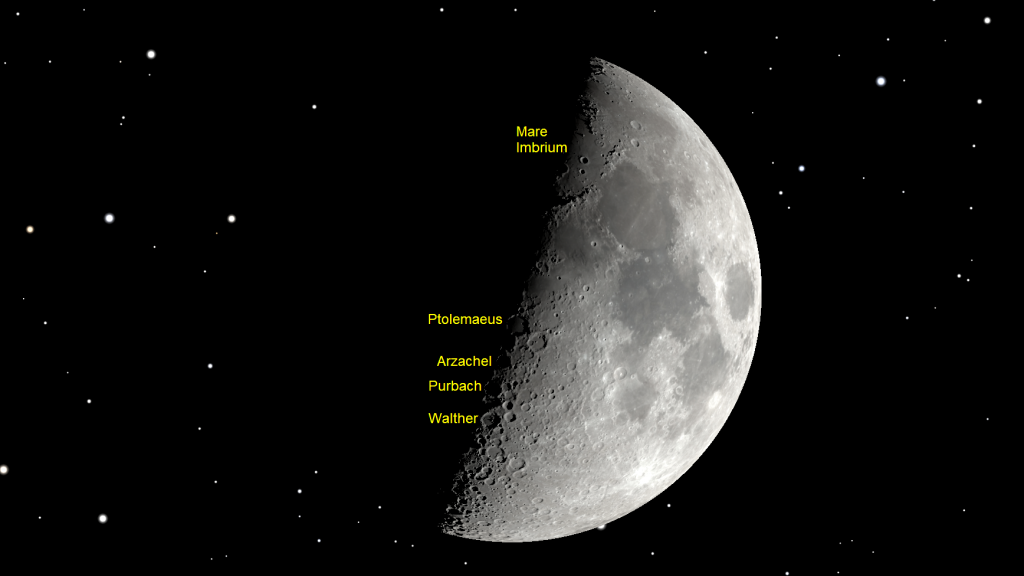

This nice photo of the First Quarter moon was taken by Michael Watson of Toronto. Michael’s galleries of astro-images are hosted on his Flickr page.

Hello, Late-June Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 25th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The evening moon will be well worth close-up looks this week. Saturn will join the late evening sky, and Venus and Mars will get coziest after sunset. I share some bright sights for moonlit nights and Jupiter, Neptune, and Uranus shine before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will dominate the evening sky this week. Everyone on Earth sees the same moon phase at about the same local time. Its rising and setting times vary by latitude, but each consecutive strip of Earth’s longitudes (i.e., each time zone) has its turn facing the moon every day.

Today (Sunday) our natural satellite will rise at about noon time because it is nearly 90° behind the sun in the sky. (You can safely view the moon through binoculars and telescopes in daytime as long as you are careful not to swing them anywhere near the sun.) When the stars come out this evening, the moon will be shining among the western stars of Virgo (the Maiden), with Leo, the Lion’s bright star Denebola sparkling to its upper right.

Sunday night’s moon will be half-illuminated, on its eastern side. That’s its right-hand side for Northern Hemisphere observers and its left side for those “down under”. The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon, early Monday morning at 3:50 am EDT, 12:50 am PDT, or 07:50 Greenwich Mean Time. But by then it will have set in the Americas.

The pole-to-pole terminator becomes a straight line only at first and third quarter. Along that boundary, which separates the lit and dark lunar hemispheres, the sun is just rising on the waxing moon – or just setting on the waning moon. The nearly horizontal rays of sunlight that illuminate the terrain beside the terminator makes it look spectacular through binoculars and telescopes. The deeper craters alongside the terminator will have bright rims and black, shadowed floors. The central mountain peaks of the larger craters will catch the sunlight, producing an island on a sea of inky black. The waxing moon is well worth revisiting on every clear evening while the terminator migrates across the moon’s globe.

Especially prominent on Sunday will be the large, 153-km wide crater Ptolemaeus, which sits close to the moon’s centre. The crater Walther (134 m wide) will be bisected by the terminator in the south and the much larger, circular Imbrium Basin will be half-illuminated in the moon’s north. Zoom in! The higher the power, the more you’ll see!

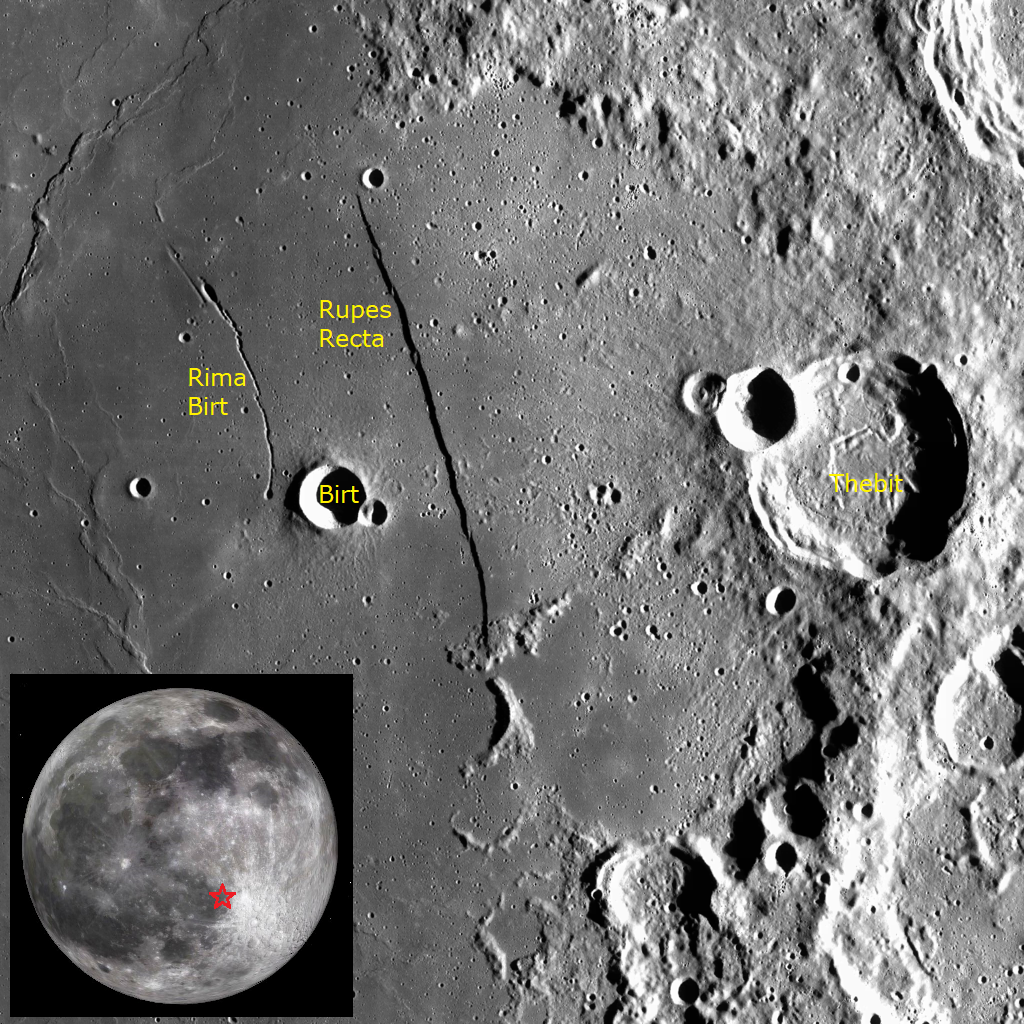

On Monday and Tuesday night, the terminator will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium, the dark patch in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The wall is visible as a straight line in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. It is most prominent a day or two after first quarter, and also on the days before the third quarter phase. For reference, the prominent crater Tycho, with its central mountain peak, is located due south of the Straight Wall. Tycho will be a dark circle on Monday and then a lit crater on Tuesday.

The waxing gibbous moon, now more than half-illuminated, will traverse the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden) until Wednesday, shining close to Virgo’s brightest star, Spica, on Tuesday night. The moon will be hosted by Libra (the Scales) on Wednesday-Thursday. By then the moon will be rising in late evening.

When the sky darkens on Friday evening, the bright, reddish star Antares “the Rival of Mars” will be twinkling several finger widths to the lower left (or celestial east-southeast) of the nearly full moon. The pair will be in the southern sky and close enough to share the view in binoculars. As the night rolls on, the moon’s easterly orbital motion will carry it closer to the star, so that observers in western time zones will see the moon shining just above, or a little to the upper left of, Antares.

Before the moon reaches Antares, however, it will cross in front of, or occult, the bright little magnitude 3 double star named Alniyat (or Sigma Scorpii), which always shines two finger widths to the right (or celestial west) of Antares. In the Greater Toronto Area, the darkened leading edge of the moon will cover those two close-together stars 12:49:30 am EDT. Alniyat will emerge from behind the moon near the big crater Vendelinus at 1:58:23 am EDT. Binoculars and any size of telescope will show the occultation. Since the times vary by location, use an app like Stellarium to look up the ingress and egress times where you live, and plan to start watching both parts of the event well ahead of time.

The bright, nearly full moon will spend Saturday night in Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), an overlooked Zodiac constellation. Next Sunday night the moon will shine within the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). Both of those nights will be ideal for exploring the moon’s dark, western half.

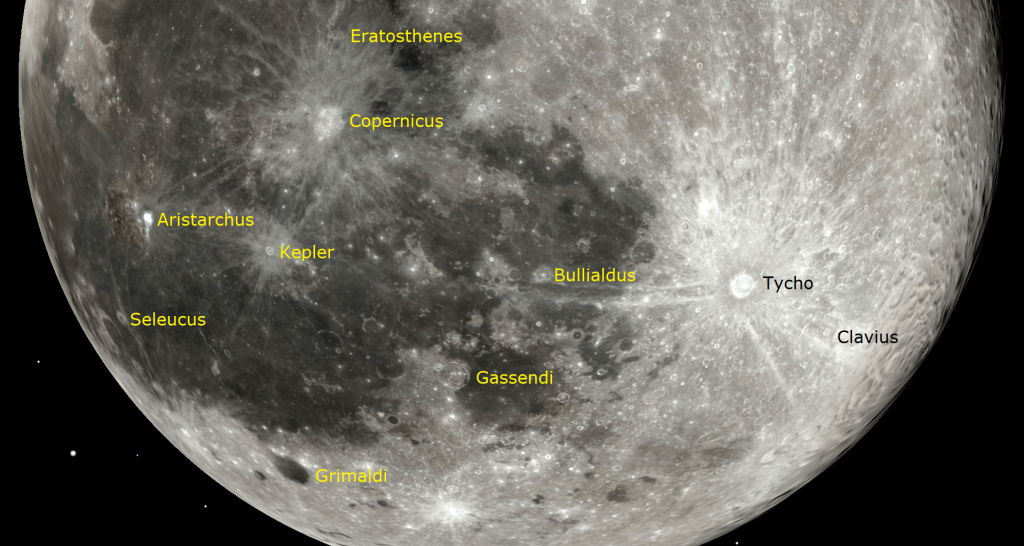

The western half of the moon is dominated by the large, dark, and irregular Oceanus Procellarum, the Ocean of Storms, and round Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains, which adjoins Procellarum to the upper right (or lunar northeast). Both are ancient basins that were excavated by huge impactors and later flooded with dark, iron-rich basalts that leaked through their floors from the moon’s interior. Since they formed after the time the moon was being heavily bombarded, the dark lunar maria are far less cratered than the bright highlands – but they are not featureless. Binoculars and telescope views reveal that the basalts vary in color and darkness due to their chemistry. When the lunar terminator is near a mare, slanted sunlight reveals the curved wrinkle ridges that ring each mare’s interior.

Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains, is the moon’s largest impact basin, measuring more than 1,145 km in diameter. It was formed during the late heavy bombardment period approximately 3.94 billion years ago. Binoculars and backyard telescope views of Mare Imbrium this week will reveal ejecta blankets around its major craters Aristillus, Autolycus, and Archimedes, the nearly-submerged ghost craters Cassini and Wallace, the isolated mountain ranges Recti, Teneriffe, and Spitzbergen, and its interior ring of subtle wrinkle ridges. The half-circle of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows, interrupts Imbrium’s western edge.

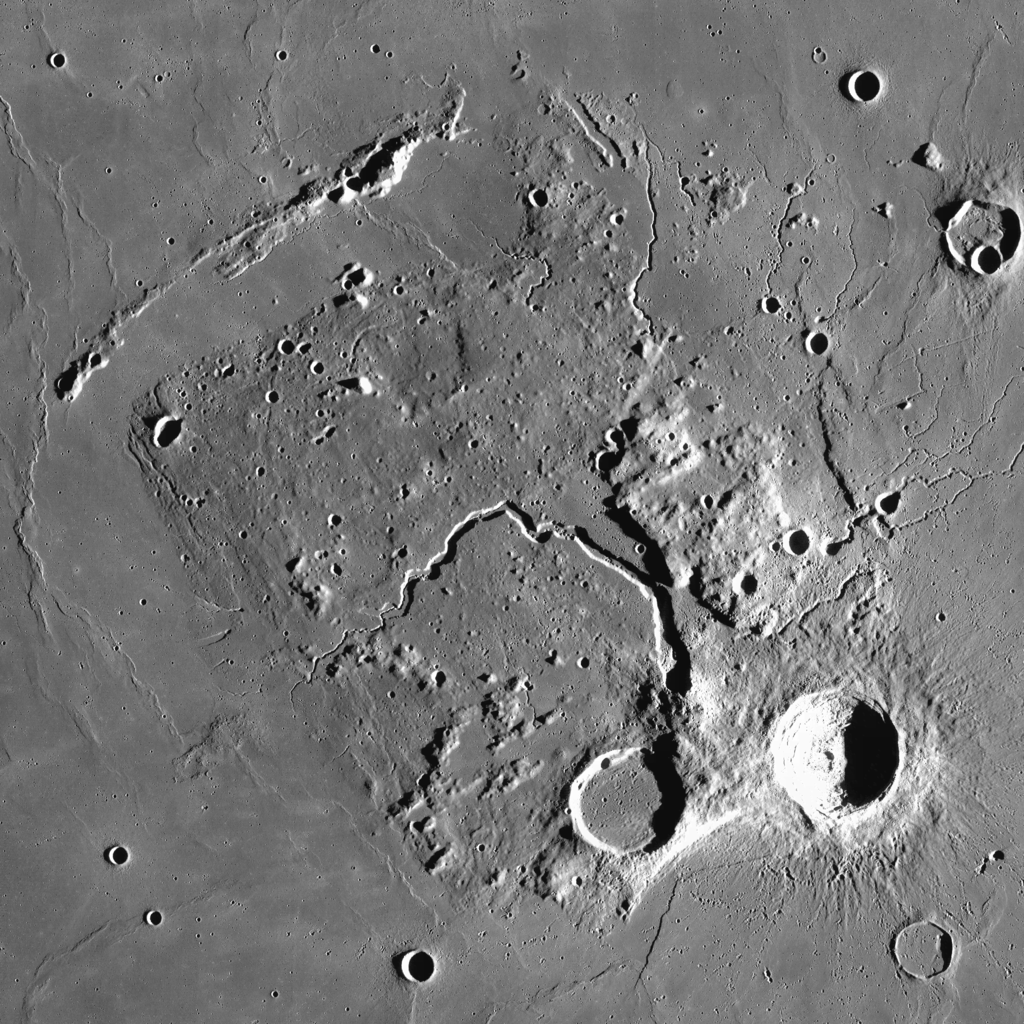

Three prominent craters break up the expanse of Oceanus Procellarum. Large Copernicus is the easternmost. Its extensive, ragged ray system intermingles with the rays of the smaller crater Kepler to its southwest. The very bright crater Aristarchus positioned to the upper left (lunar northwest) of them occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door crater Herodotus and slithers across the plateau. I never tire of looking at it!

The Planets

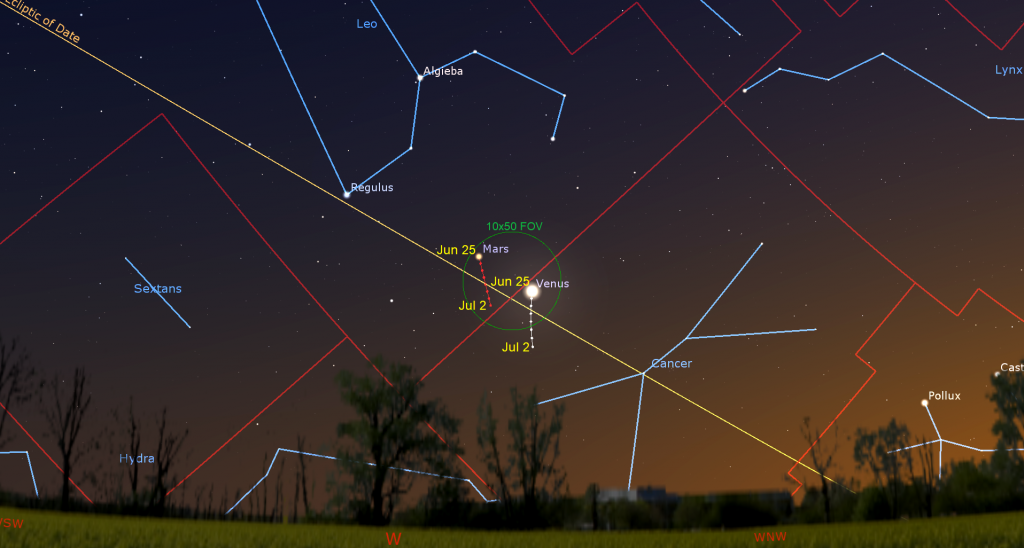

Venus and Mars have been shining in a dark western evening sky for quite some time – but they will now be sinking more and more into the post-sunset twilight. Brilliant Venus will first pop into view in the lower part of the darkening western sky at sunset. Before long, Regulus, the brightest star in Leo (the Lion), will appear a generous fist’s width to Venus’ upper left. The faint, reddish speck of Mars will shine weakly between Venus and Regulus, but closer to Venus.

On Friday evening, the separation between Venus and Mars will decrease to a minimum of several finger widths, or 3.6°. After that, their separation will increase as Venus drops sunward faster than Mars. The pair of planets will continue to share the view in your binoculars until about mid-July. Keep in mind that brilliant Venus is situated in space between Earth and the sun – about 80 million km away from you – while Mars is on the far side of the solar system from us – about 326 million km away. Yes, Mars is smaller and less reflective than Venus, but that difference in distance greatly contributes to their vastly different brightness.

Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will show a 33%-illuminated crescent that is waning and growing slightly larger each day as it ventures into the space between Earth and the sun. To see the planet’s shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at Venus while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened. Good binoculars can hint at Venus’ non-round shape. Like Venus, Mars will look best in a telescope while it is highest, right after dusk, but its ruddy disk will look tiny under any magnification.

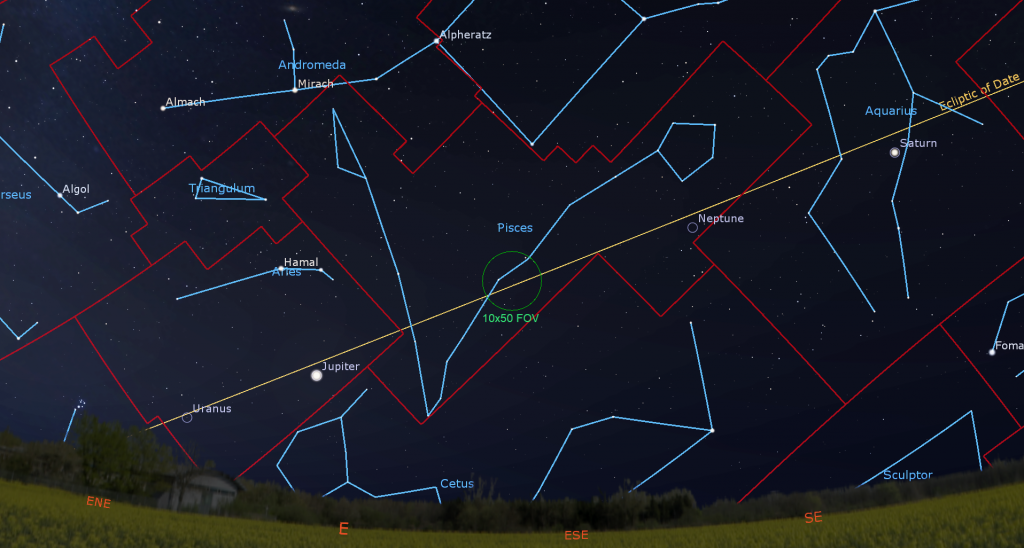

The next planet to appear will be Saturn. Its yellowish dot will rise over the eastern horizon around midnight this week, making it an evening planet once again after a long absence. The best time to view Saturn will be before dawn, when it will be located a third of the way up the southern sky among the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Even a small telescope can show Saturn’s ring and some of its moons. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on to mid-winter!

The planet Neptune, 600 times fainter than Saturn, will be located two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 19° to its celestial east. On Saturday, the eastward prograde motion of Neptune through the background stars of western Pisces will slow to a stop. After that it will commence a very small westward retrograde loop that will last until early December. For the next few weeks Neptune’s tiny, faint, blue disk will be observable in telescopes while it crosses the lower part of the southeastern sky between about 2 and 4 am local time. The medium-bright star 27 Piscium shining 2 degrees below Neptune will guide you. Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the outer planets “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars.

Rising next, at around 2:30 am local time, will be the brilliant white dot of Jupiter, which will look about 16 times brighter than Saturn. Jupiter will be a good distance above the eastern rooftops when the sky starts to brighten before 4:30 am, but you should be able to see the giant planet easily until almost sunrise. A few weeks from now, Jupiter will rise early enough to shine in a dark sky amid the stars of its host constellation, Aries (the Ram). Jupiter will join the evening planets by the second week of August, and we’ll be able to view it from then until March, 2024.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter next Sunday morning.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Jupiter will be followed across the sky by Uranus, which will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to the bright planet’s lower left (or celestial east). Blue-green Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. It will become much easier to see in the coming weeks.

Some Moonlight-Friendly Sights

Even though the moon will brighten evening skies all over the world this week, there are still plenty of sights to see – with your unaided eyes, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes.

After dusk in late June, Vega, Deneb, and Altair are the first stars to appear in the darkening eastern sky. Those three bright, white stars form the Summer Triangle asterism – an annual feature of the summer sky that actually remains visible until the end of December! Vega in Lyra (the Harp) is the highest and most easterly of the trio. At magnitude 0.03, Vega is the brightest star in the summer sky, mainly due to its relative proximity to the sun – it’s only 25 light-years away from us. Magnitude 0.75 Altair, in Aquila (the Eagle), occupies the lowest, southern corner of the triangle. Altair is only 17 light-years from the sun. By contrast, Deneb, which shines somewhat less brightly than Vega at magnitude 1.25, is a staggering 2,600 light-years away from us. It ranks so high in visible brightness because of its greater intrinsic luminosity. It’s among the farthest stars visible to unaided human eyes. Deneb marks the tail of Cygnus (the Swan).

Look for the modestly-bright star sitting in the centre of the Summer Triangle – like the core of Doc Brown’s flux capacitor. That pretty, multi-coloured star named Albireo marks the head of Cygnus (the Swan). The Milky Way passes between Vega and Altair and through Deneb, which will sit high overhead in Cygnus as dawn begins to break. In binoculars, Albireo splits into a close-together pair of stars. A telescope will show them to be blue and yellow. Double stars like Albireo were given a single name because their dual nature was unknown until telescopes were invented much later.

Stars shine with a colour that is produced by their surface temperatures, and this is captured in their spectral classification. The three bright stars of the Summer Triangle are all A-class stars that appear blue-white to the eye and have surface temperatures in the range of 7,500 to 10,000 K. Look high in the southwestern sky for orange Arcturus, a K-class giant star with a temperature of only 4,300 K. Over the southern horizon, reddish Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion), is an old M-class star with a surface temperature of 3,500 K. By comparing these stars colors’ to other stars, you can estimate those stars’ temperatures. The classification letters, from hottest to coolest are: OBAFGKM. Can you think up a mnemonic phrase to remember the order? I have one.

After looking at Arcturus, turn your gaze to its upper left and look for the incomplete ring of stars forming the Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown). Its brightest star, white Alphecca acts as the diamond. A triangle of stars a fist’s diameter below Corona Borealis form the head of Serpens (the Snake), which is being held aloft by Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). I’ll tour you through his treasures soon.

The constellation of Lyra (the Harp) is positioned high overhead in late evening toward the end of June. This constellation features a coffee and a donut! Keen eyes might reveal that the star Epsilon (ε) Lyrae, located just one finger’s width to the lower left (or 1 degree to the celestial east) of the bright star Vega (Alpha Lyrae), is a double star. Binoculars or a small telescope will certainly show the pair. Examining Epsilon at high magnification will reveal that each of the stars is itself a double – hence its nick-name, “the double-double”. To see the donut, aim your telescope midway between the stars Sulafat and Sheliak, which form the southern end of Lyra’s parallelogram. Messier 57, also known as the Ring Nebula, will appear as a faint, grey ring. Higher magnification works well on this planetary nebula – which is the corpse of a star that had a similar mass to our sun.

Early this week, before the moon gets to close to it, look low over the southeastern horizon for one of the best asterisms in the sky – the Teapot in Sagittarius (the Archer). This informal star pattern features a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the east and Kaus Australis on the west, a triangular pointed spout pointing west, marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form the teapot’s handle. The asterism reaches maximum height above the southern horizon around 2 am local time, when it will look as if it’s serving its hot beverage – with the steam rising as the Milky Way!

Stars to Wish Upon

If you missed last week’s information about the first stars to appear each evening, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On the first clear weeknight this week the public are invited to Bring their Own Binoculars to the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

If it’s sunny on Saturday morning, July 1 from 10 am to noon, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside the main doors of the Ontario Science Centre for Solar Observing. Come and see the Sun in detail through special equipment designed to view it safely. This is a free event (details here), but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, July 4 at 3:30 pm EST. Delayed from June 20, we’ll focus on how to use star charts and which ones are best. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!