‘Tis the Solstice Season, the Queen’s Treats, a Coming Comet, and the Little Dipper Spills Meteors while the Moon Wanes in the Morning!

This widefield photograph spanning about 10 degrees of of the sky near Cassiopeia was taken by Adrian Klamerius. It shows the redly-glowing Hydrogen gas clouds of the lovely Heart and Soul Nebulas, and the spectacular Double Cluster. NASA APOD for September 24, 2016.

Happy Solstice, Winter Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 15th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where all the old editions will be archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

While it transitions through its last quarter phase, the moon will occupy the post-midnight-to-morning sky for observers worldwide this week, leaving evenings nice and dark for meteor hunting and viewing deep sky delights, especially around Cassiopeia. At the end of the week, the December Solstice will kick off Northern winter and Southern summer. At sunset, very bright Venus will climb the western sky while dimmer Saturn descends it. Reddish Mars will shine below a bright double star in the pre-dawn east, the Little Dipper will spill meteors, and a modest comet will be lurking in the eastern evening sky. Here are your Skylights!

‘Tis the Seasonal Change

Happy Holidays, everyone! Or, as we astronomers say, “Have a Happy Solstice and a Merry Perihelion!”

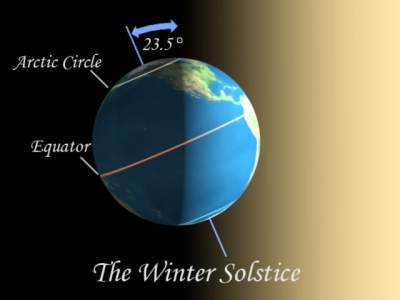

For the Northern Hemisphere, the beginning of winter, also called the Winter Solstice, will occur on Saturday, December 21 at 11:19 pm Eastern Time (or on Sunday, December 22 at 04:19 Greenwich Mean Time). At that precise moment, the north pole of Earth’s axis of rotation will be tilting directly away from the sun.

Every day at local noon the sun reaches its highest position (or culmination) in the sky for that day. But on the Winter Solstice, that position is the lowest (i.e., farthest south, celestially) for the entire year. The low culmination also means that the sun needs less time after sunrise to reach noon – so Northern Hemisphere dwellers receive the shortest duration of daylight and the longest nights for the year. The sunlight that northerners do get this at time of year is also weaker because it’s spread over a larger area, the same way a flashlight beam looks dimmer when you shine it obliquely at a wall (try it!). The dilution effect is stronger the farther from the Equator you live.

Fewer hours and weaker sunlight result in less received solar energy (insolation) and therefore colder temperatures! It is not the case, as some people think, that days are colder in winter because we are farther from the Sun (a position called aphelion). That event happens every year in early July. On the contrary – Earth’s minimum distance from the Sun (perihelion) occurs every January 4, or thereabouts.

After Saturday, our days will slowly start to grow longer again. For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun will attain its highest noon-time height for the year on the December solstice, and kick off their summer season. Their winter will commence six months from now, at the June Solstice.

Some scholars think that Christmas was deliberately scheduled close to the December solstice, and Easter close to the Vernal Equinox, because early non-Christian “pagans” were already holding celebrations to mark the astronomical changing of the seasons.

The Moon and Planets

The moon will commence this week shining in the late evening sky as a bright, but waning gibbous orb sitting among the stars of Cancer (the Crab). On Monday night, the moon will land less than four finger widths to the upper left (or 3.5° to the celestial northwest) of the bright, white star Regulus, which is the brightest star in Leo (the Lion).

By mid-week, the waning crescent moon will exit Leo for Virgo (the Maiden) and will be rising around midnight, then lingering into the daytime morning sky. The moon will reach its last quarter phase minutes before midnight Eastern Time on Wednesday night. At this phase, the moon is illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn sun.

Later in the week, early risers can see the crescent moon hop past the bright white star Spica in Virgo. Look for that bright star sitting a generous fist’s diameter (11°) below the moon on Friday morning, and a generous palm’s width (8°) to the right of the moon on Saturday morning.

Te end the week, the very slim moon will rise next Sunday at about 3:50 am local time and will be positioned about a fist’s width above (or 9° to the celestial northwest) of Mars in the east-southeastern pre-dawn sky. The duo will make a pretty sight in binoculars until just before sunrise.

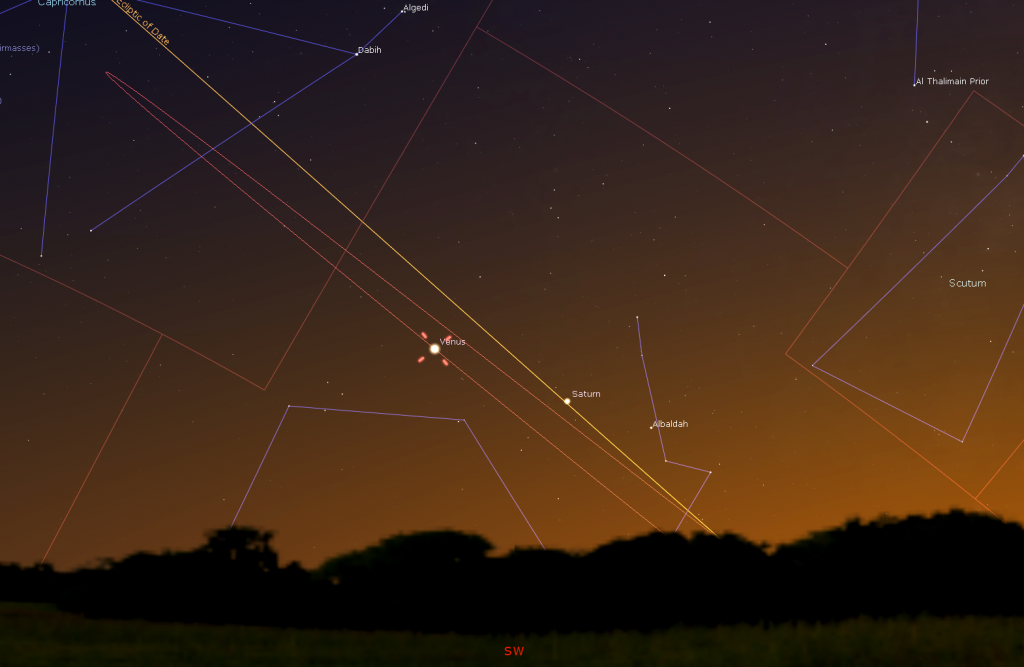

Venus will continue its lengthy evening appearance this week, shining very brightly in the southwestern evening sky in twilight until it sets at about 7 pm local time. While aircraft in that part of the sky may look as bright as our sister planet, Venus will be distinguishable by its steady, unblinking light. Periodic views of Venus in your telescope over the upcoming weeks will reveal that its already less-than-fully-illuminated disk is waning as it swings wide of the sun. Try to view the planet while it is higher in the sky around 5 pm local time (but be sure not to point your telescope anywhere near the sun).

You can still use bright Venus to locate dimmer Saturn. The ringed planet is being carried towards the sun by Earth’s motion while Venus is rapidly heading in the opposite direction. Tonight (Sunday) Saturn will be located a slim palm’s width to the lower right of Venus (or 5.3° to the celestial west). Next Sunday evening, Saturn will be 1.3 fist diameters to Venus’ lower right.

This winter, evening planet-watchers will have to settle for Venus and the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. Despite their relatively dim magnitudes and small disk sizes, the delightful colours of those two remote planets make them worthy of a look in backyard telescopes – although they can be tricky to find.

Distant and dim, blue Neptune will set before 11:30 pm local time this week, so you should try to observe it as soon as the sky is dark, when Neptune will be at its highest – a little less than halfway up the southern sky. Neptune is situated among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and is positioned a thumb’s width to the right (or 1.5 degrees to the celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. Both blue Neptune and that golden-coloured star will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at low power. While the bright moon is out of the night sky this week, magnitude 7.9 Neptune will be visible in binoculars. Find Phi Aquarii first and then locate nearby Neptune. Remember that binoculars will display the true positions of the objects, but your telescope will flip and/or mirror-image the view. (To find out what your telescope does to the image, see how it changes the appearance of the moon, and make a note of the result.)

Blue-green Uranus is observable from dusk until the wee hours of the night. It is located a generous palm’s width to the left (or 7° to the celestial east) of the modest stars that form the “V” of Pisces (the Fishes). Uranus is also below (or to the celestial south of) the medium-bright stars of Aries (the Ram), and above the head of Cetus (the Sea-Monster).

Shining at magnitude 5.7, Uranus is bright enough to see under dark sky conditions with unaided eyes and with binoculars – or through small telescopes under less-dark conditions. To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here. If you view Uranus at about 8:30 pm local time, it will be highest in the southern sky – and you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

Red-tinted Mars is lurking in the eastern pre-dawn sky. It will rise at about 4:45 am local time and remain visible until dawn. The bright star sitting to the upper right of Mars is the double star named Zubenelgenubi in Libra (the Scales).

From now until October, 2020, Mars will continually grow in brightness – and will increase in apparent size when viewed in telescopes. In fact, the 2020 Mars opposition is a terrific reason to get a telescope now, so you can practice viewing the planet during the spring and summer months of 2020 – especially when the moon, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn all meet up next March 18! If you missed my recent note about buying a beginner telescope, I posted it here.

I’ll post sky charts for all the observable planets here.

Andromeda’s Family – a Story in the Stars

The late fall and winter evening sky features a group of easy-to-see constellation that are the characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – Princess Andromeda and the hero Perseus. Over the next few weeks, I’ll tour you through the individual constellations – telling you how to find them, and highlighting some their best sights in binoculars and telescopes. Once upon a time…

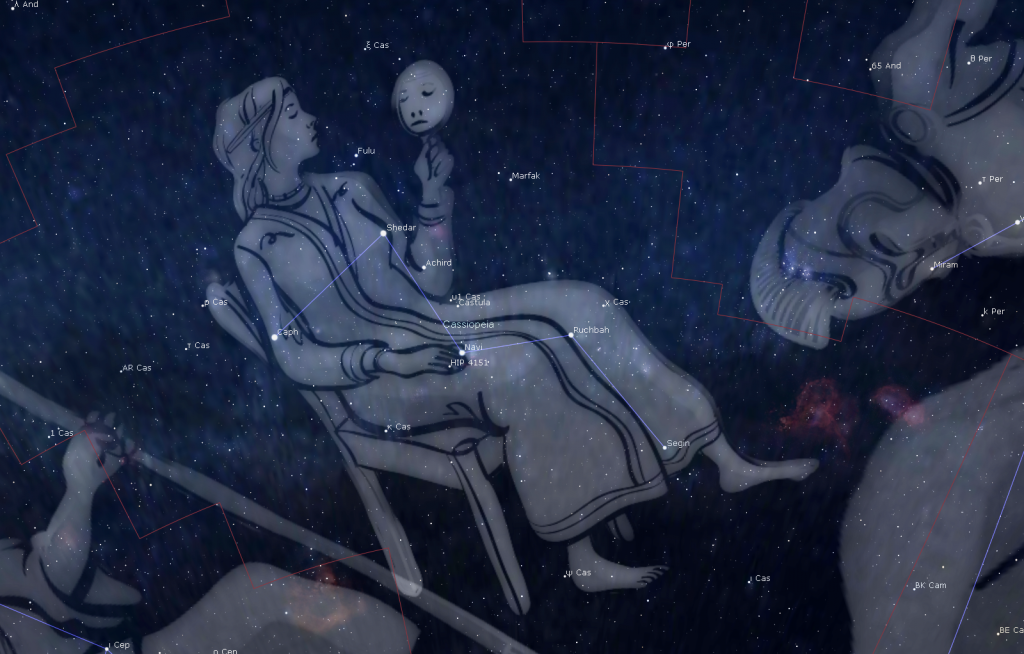

In Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was the queen of Ethiopia, and married to King Cepheus. When Cassiopeia boasted of their daughter Andromeda’s unrivalled beauty, the sea nymphs took offence and asked Poseidon to unleash the fury of Cetus the Sea-monster on Ethiopia’s coast. When asked how to rectify the situation, Poseidon ordered Cepheus to chain Andromeda to the seashore, where Cetus the Sea-monster would take her and return to the sea. Just in the nick of time, the hero Perseus, fresh from defeating the Gorgon Medusa and still carrying her head in a bag, flew to Andromeda’s rescue on the winged horse Pegasus. The couple lived happily ever after, but the queen and her husband were banished to the stars, never resting as they circle the spinning north celestial pole – and spending much of the time hanging upside down! Later, Andromeda, Perseus and Pegasus, and Cetus were all given places in the sky.

Evenings during this time of the year are ideal for taking in the sights of the constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). Her distinctive crooked “W” of five bright stars, each about four finger widths from the next, is situated high the northeastern evening sky (or over the northern horizon, if you live closer to the equator). Cassiopeia is circumpolar – so close to the North Celestial Pole (and therefore Polaris) that, for Canadians and other mid-latitude observers, the constellation never sets.

If you face north and look up in mid-evening, you’ll find Cassiopeia oriented upside-down, appearing more like an “M” with its right-hand peak squashed. Many world cultures have interpretations for this distinctive set of bright stars. The Inuit saw a blubber oil lamp and stand. The Navajo saw a female form that revolved around the pole. Pacific Islanders saw a great bird. Biblical scholars replaced the queen of Ethiopia with Bathsheba, Mary Magdalene, and others.

In classical astronomical charts Cassiopeia is depicted as sitting in a chair, her hand combing her hair. The bright star at the left-hand (or western) tip of the constellation is named Caph (“hand”). Also designated Beta (β) Cassiopeiae, it is a yellow-white star located 54 light-years away from us. This aging star is beginning its transition to a red giant. (In 1603, in his star atlas Uranometria, German astronomer Johann Bayer assigned Greek letters to each constellation’s stars in descending order of brightness ranking.)

The bright star located second from the left, and marking the point of the “M” or “W”, is named Shedir or Shedar, Arabic for “breast”. Its Bayer designation is Alpha (α) Cassiopeiae, although it can be outshone occasionally by another of Cassiopeia’s stars (see below). Shedir is another aging giant star. It is located 229 light-years away from us. Viewed in binoculars, you’ll see that Shedir is an orange-ish star with a small companion.

The star in the middle of the constellation that marks the queen’s waist doesn’t have an Arabic name. Instead it is designated Gamma (γ) Cassiopeiae. It also has the unofficial nickname Navi, which is Apollo astronaut Gus Grissom’s middle name spelled backwards. This white star is located 549 light-years from us, and shines with a brightness that varies irregularly due to a high rate of spin and periodic gas ejection. At the moment, Gamma is shining a little brighter than Shedir and Caph.

The fourth star from the left, and the shallower point of the “M” or “W”, is named Ruchbah or Rukbat (“knee”). Bayer assigned Delta (δ) Cassiopeiae. Ruchbah is a whitish colour eclipsing binary star only 99 light-years away from us that dims a little in brightness when an orbiting dimmer companion star partially blocks its light every 25 months.

The last of the Cassiopeia’s brightest five stars Epsilon (ε) Cassiopeiae marks the queen’s foot. Its nickname, Segin, is of unknown origin. This modest looking star is actually a blue-white giant star located about 440 light-years away. It’s about six times the mass of our Sun, but 2,500 times more luminous!

See if you can spot a star between Shedir and Navi. That’s Achird, the queen’s mirror or comb – although some sources claim that the name means “girdle”. Achird is a yellow, sunlike star located only 19 light-years from Earth. On the opposite side of Shedir from Achird is dimmer Fulu, a hot blue star located nearly 600 light-years away from us. The last named star in Cassiopeia is Marfak, or Theta (θ) Cassiopeiae. Marfak is located about four finger widths to the upper right (or celestial south) of Shedir. It’s a widely-spaced double star.

The outer rim of our Milky Way galaxy passes directly through Cassiopeia, meaning that the area is rich in interesting objects and star fields. One of my favorite objects can be seen in binoculars or a backyard telescope. It’s an open cluster of stars designated as NGC 457, but I prefer its common names – the Owl Cluster, or ET Cluster, or Dragonfly Cluster. The cluster was discovered by William Herschel in 1787 and is more than 7,900 light-years away! It consists of two prominent, brighter yellow stars that form the eyes. A sprinkling of dimmer stars forms the owl’s body and feet, and two curved chains of stars look like upswept wings.

Be aware that the critter is positioned with its head pointing away from Cassiopiea. This will be the case in binoculars, but your telescope will flip the image. Locate the owl by taking Navi and Ruchbah and making them the two vertices of a right-angle triangle. The cluster sits at the third vertex, where the 90 degree corner is. It’s about four finger widths above Ruchbah – as if the queen is bouncing a baby owl on her knee!

Sweep your binoculars a few finger widths to Caph’s upper left and look for a knot of stars named Caroline’s Rose. Another bright star cluster named NGC 129 sits between Caph and Navi. Sitting outside of Cassiopeia, a generous palm’s width to the right of Ruchbah, you’ll find the spectacular and very bright Double Cluster. It is visible with unaided eyes and pops in binoculars.

Owners of large telescope can look for the large nebulas that reside in Cassiopiea. Extending a line from Shedar to Caph by a distance equal to their separation brings you to the Bubble Nebula (NGC 7635) and the Salt-and-Pepper Cluster (NGC 7654). There’s a smaller nebula less than half a finger’s width below Navi. And near the far right of the constellation’s official boundary are the spectacular Heart and Soul Nebulas. They sit only two degrees apart (two finger widths) and can be found only about a palm’s width to the right of the star Segin.

While you’re gazing at the queen’s treasures, use the left half of Cassiopeia as an arrowhead that points directly at the great Andromeda Galaxy. The galaxy is approximately 1.5 fist widths (at arm’s length) from the tip of the arrow. At 2.5 million light years away, its faint smudge is among the farthest objects visible to unaided human eyes. Under dark skies, you might be able to detect its glowing patch that spans more than two finger widths across, or several full moon diameters. In actuality, it measures six moon diameters across and two moons wide!

I’ll post a sky chart here.

A Binocular Comet

A relatively dim comet will be traversing the northeastern evening sky this winter. Designated C/2017 T2 (PANSTARRS), it is currently at magnitude 9.0 among the stars of Perseus (the Hero). That means that it is conveniently positioned for evening viewing – but you’ll need either big binoculars or a backyard telescope to see it.

The place to look for the comet is located about halfway up the northeastern sky in early evening – a generous fist’s diameter above the very bright star Capella. Another medium-bright star named Mirfak is located to the comet’s upper right.

Viewed in binoculars and telescopes, the comet will appear as a dim fuzzy patch that might exhibit a faint greenish core. It’s still too early to see a tail, but the comet is expected to brighten more in the coming month. Stay tuned for updates!

Meteor Shower News

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, continues until December 16 – so you might catch a few more of them for the beginning of this week.

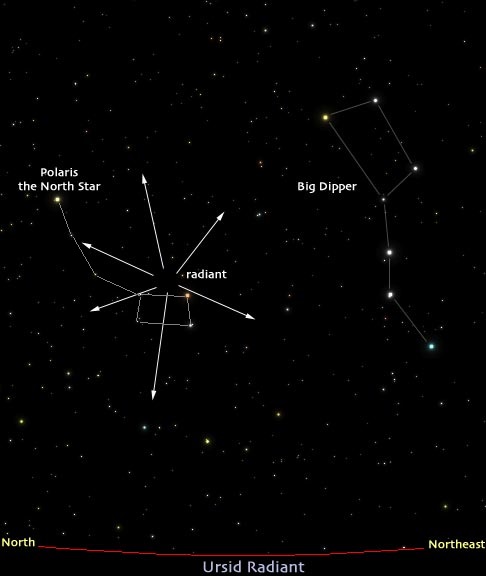

The annual Ursids Meteor Shower runs from December 17 to 23. This year, it will peak during the wee hours of Saturday, December 22, when seeing 5 to 10 meteors per hour is possible under dark skies. The best time to watch will be from midnight until dawn that morning, but you might see an occasional Ursid during the preceding evening. For the Ursids this year, the moon will be a waning crescent that rises in before dawn on the peak date, setting up good meteor watching conditions. The shower’s radiant is above the Little Dipper in Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), near Polaris, but the meteors can appear anywhere.

To see the most meteors, find a wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors – their field of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. If the peak night is cloudy, the night on either side of that date will be almost as good. Happy hunting!

Spotting Satellites

If you missed last week’s information about spotting Artificial satellites, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

With the Holidays fast approaching, organizations have suspended their public events until January.

This Winter spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday afternoon, January 12, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 2 pm, and repeat from 2 to 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older, and the Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!