Valentine’s Night Sights after the Full Snow Moon Moves on, Venus Gleams Brightest, and Algol Alternates!

Adrien Klamerius took this image of the Heart (upper left) and Soul (lower right) nebulas in Cassiopeia, also known as IC 1805 and IC 1848, respectively. The Double Cluster as at top centre. The area of sky covers about 10 degrees, or a fist diameter. NASA APOD for Sep 24, 2016.

Hello, Lovers of the Night Sky!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 9th, 2025 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Instagram and Bluesky as astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will reach and pass its full phase this week, but it will start to rise late enough for us to do some winter stargazing this coming weekend. Valentine’s Day night will bring us Venus and maximum brightness and the rest of the planets that have been following her across the sky this winter. I also highlight some love-connected sights, Medusa “closing her eye”, and the return of spring zodiacal light. Read on for your Skylights!

Valentine’s Night Treats

While none of the official constellations are heart-shaped, there are some romantic duos in the stars that you can see with your unaided eyes on Valentine’s Day night – despite the bright moonlight.

If you look about halfway up the western sky during mid-evening you’ll see the stars of Princess Andromeda extending upwards from the top corner of the big square of Pegasus (the Flying Horse). Andromeda’s hero, and eventual husband, Perseus is the constellation directly above her. Its centre is marked by the bright star Mirfak. Between those lovers, and a few fist diameters to their right (or 30° to the celestial northwest of them), are her parents’ constellations, w-shaped Queen Cassiopeia and boxy King Cepheus.

To celebrate fraternal love, we have the constellation of Gemini (the Twins) located in the evening sky to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of Orion (the Hunter). The two medium-bright stars Pollux (the lower one) and Castor (the upper one) mark the heads of the two brothers. Note that Pollux is a wee bit brighter and warmer in colour than Castor. Viewed through your telescope, Castor splits into a nice double star.

For a different type of devotion, we can highlight Orion the hunter’s faithful companion Canis Major (the Big Dog). Canis Major forever and faithfully follows his master around the sky – although he might be more interested in chasing Lepus (the Hare), the constellation that sits to his west, below Orion. The big dog’s stars are distributed around their brightest member, Sirius, also known as the Dog Star (and Alpha Canis Majoris). On mid-February evenings, Sirius reaches its highest point over the southern horizon at around 9:30 pm local time – while sparkling like a diamond! Sirius is a hot, white, A-class star located only 8.6 light-years from Earth – part of the reason for its brilliance. For mid-northern latitude observers, Sirius is always seen in the lower third of the sky, through a thicker blanket of refracting atmosphere. This causes the strong twinkling and flashes of color the Dog Star is known for.

Look less than a finger’s width to the lower right of the bright star Alnitak – the star at the eastern, left-hand end of Orion’s Belt – for a medium-bright star named Sigma Orionis or σ Ori. When viewed in powerful binoculars or a backyard telescope, you’ll see that Sigma Orionis is in the middle of a pretty little group of about 10 stars arranged in a dart shape – like Cupid’s Arrow!

Wait until next week’s moonless nights for the following romantic targets. Beside Orion, on his eastern (left) side, and above Canis Major, is the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn). Its stars are mainly of medium and low brightness – but it sits squarely astride the Milky Way and contains some delightful sights! The Rosette Nebula (also known as NGC 2244) is a beautiful rose-shaped cloud of reddish gas with a clump of bright little stars in its centre. It is located about a fist’s diameter to the left of Orion’s shoulder star Betelgeuse. The Rosette is visible in binoculars, but only long-exposure photos will reveals its colourful rose.

A little star named Theta Canis Majoris sits a palm’s width to the upper left of Sirius. It marks the doggy’s nose! If you draw an imaginary line from Sirius to Theta and then double its length, you’ll come to a small open star cluster named Messier 50, also known as the Heart-Shaped Cluster and NGC 2323. The cluster is visible in binoculars – but try viewing it through your telescope. I don’t think that the heart shape is all that obvious – but the cluster of mainly white stars features the special treat of a bright, golden star at its lower edge.

Cassiopeia (the Queen) hosts the Heart Nebula, also known as the Valentine Nebula and IC 1805. It’s a truly beautiful object located 2,500 light-years away from us. This nebula and its companion the Soul Nebula (IC 1848) are located between Perseus and Cassiopeia – about three finger widths to the right of the Double Cluster. It’s too faint to see unless the sky is very, very dark – but many lovely photographs of it have been published. A faint, but rich star cluster named Caroline’s Rose (NGC 7789), named for the renowned woman astronomer Caroline Herschel, sits a few degrees below the bottom stars of Cassiopeia.

Finally, to celebrate your favorite someone, locate and view their Birthday Star. That’s a star that is located at the same distance from Earth (expressed in light-years) as that person’s age in years. In other words, the light you see now started its journey towards us at the time they were born. Visit this page and scroll down the list to find birthday stars for different years old – or use this page to enter a birth date. Then you can look for that star in the night sky – if it happens to be visible at this time of year from your location. It’s fun! And the stars for kids’ ages tend to be the closest and brightest stars in the night sky – and easy to see, even from the city.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a mid-northern latitude location where the sky is free from light pollution, you might be able to spot a phenomenon called the zodiacal light during the two weeks that precede the new moon arriving on February 27. Starting on Friday, February 14, after the evening twilight has faded, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below the planets Venus and Saturn. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year.

Watch Medusa Blink

On mid-February evenings the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) is located very high in the western sky. The easiest way to identify the constellation is to look for Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak, which shines midway between the W-shape of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the even brighter, yellowish star Capella in Auriga (the Charioteer) above it. This year, very bright Jupiter has been shining about the same distance away, but to Mirfak’s upper left.

The second brightest star of Perseus is Beta Persei (β Per), better known as Algol, from the Arabic “Ra’s al-Ghul”, which means “the Demon’s Head”. Algol represents the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying. The star represented the god Horus in Egyptian mythology and was Rosh ha Satan “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew.

There’s a good reason for these scary associations. Ancient sky-watchers noticed that Algol is variable. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star with an orbit nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of (or eclipses) the much brighter main star. As the dim star moves more and more in front of the main star over a five hour period, the light we see steadily drops in brightness. Then it ramps up again during another five hours as the small star moves clear – until the eclipse is over. Algol is the archetype for all eclipsing binary star systems, and is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers.

The easiest way to monitor Algol’s variability is to note how bright that star looks compared to other, non-varying stars near it. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol shines at magnitude 2.1, similar in brightness to Almach in Andromeda (the Princess). That bright star is located a generous fist’s diameter below Algol (or 12° to its celestial west). While dimmed, Algol shines at magnitude 3.4, about the same brightness as the star Gorgonea Tertia (or Rho Persei), which is located just two finger widths to Algol’s left (or celestial south). Use your unaided eyes or binoculars to compare them.

On Sunday evening, February 16 at 6:56 pm EST (or 23:56 Greenwich Mean Time), Algol will start to fade from its usual brightness. At that time it will be shining very high in the western sky below Capella. Five hours later, at 11:56 pm EST (or 04:56 GMT on Monday), Algol will have faded to its minimum brightness. It’s location at that time will be in the lower part of the northwestern sky.

The Moon

For most of this week, the moon will dominate the evening sky while it passes its full phase. Then it will start to rise later, leaving early evenings worldwide darker for star-lovers.

Today (Sunday) Earth’s natural night-light will rise in early afternoon, giving you the opportunity to see it in the daytime. The bright planet Mars will appear just a few finger widths to the moon’s upper right as the sky begins to darken at sunset – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Gemini’s two bright stars Castor and Pollux will sparkle to their left (or celestial northeast). The grouping will climb highest, in the southern sky, around 10:30 pm local time and then set in the west before dawn on Monday. By then the orbital motion of the moon and the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift the moon farther from, and above, Mars.

Hours before it rises in the Eastern Time zone, the moon will cross in front of (or occult) Mars for observers located in the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, Iceland, most of Scandinavia, most of Russia, eastern Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and most of China. Lunar occultations of planets are safe to observe with your unaided eyes, and are especially good in binoculars and through telescopes. Use an app like Stellarium to look up the timings where you live.

The bright moon will rise about 70 minutes later every day. On Monday, it will outshine the modest stars of Cancer (the Crab) that surround it. On Tuesday, the moon will appear to be full when it rises in the east around 5 pm local time, just getting ready to slide into next-door Leo (the Lion).

The moon will officially pass its full moon phase at 8:53 am EST or 5:53 am PST on Wednesday morning in the Americas, which converts to 16:56 Greenwich Mean Time. So, for observers there, the moon will look just a sliver less than full on both Tuesday night and Wednesday evening. The thin, non-illuminated strip along the lower left (or lunar west) edge of the moon on Tuesday night will switch to the moon’s upper right (or lunar east) side on Wednesday. That’s because the moon’s angle from the sun (or elongation) will change from 173° to 186° over 24 hours – i.e., crossing the 180° position). Binoculars or a backyard telescope will easily show you the phenomenon.

When full, the moon always rises around sunset and sets around sunrise because it is opposite the sun. The February full moon always shines in or near the stars of Leo (the Lion), which is half the sky away from the sun, currently residing in the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Winter moons also climb very high in the late-night sky because the winter sun is so low at noon.

The moon has always shone its reflected sunlight down upon humans on Earth. At some point, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve (sometimes thirteen) full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night. It lit the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and workers in the fields devoting extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons. The next “two full moons within a calendar month” event will happen in May, 2026.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The indigenous Anishnaabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) people of the Great Lakes region call the February full moon Namebini-giizis “Sucker Fish Moon” or Mikwa-giizis, the “Bear Moon”. For them it signifies a time to discover how to see beyond reality and to communicate through energy rather than sound. The Algonquin call it Wapicuummilcum, the “ice in river is gone” moon. The Cree of North America call it Kisipisim, the “the Great Moon”, a time when the animals remain hidden away and traps are empty. For Europeans, it is known as the Snow Moon or Hunger Moon.

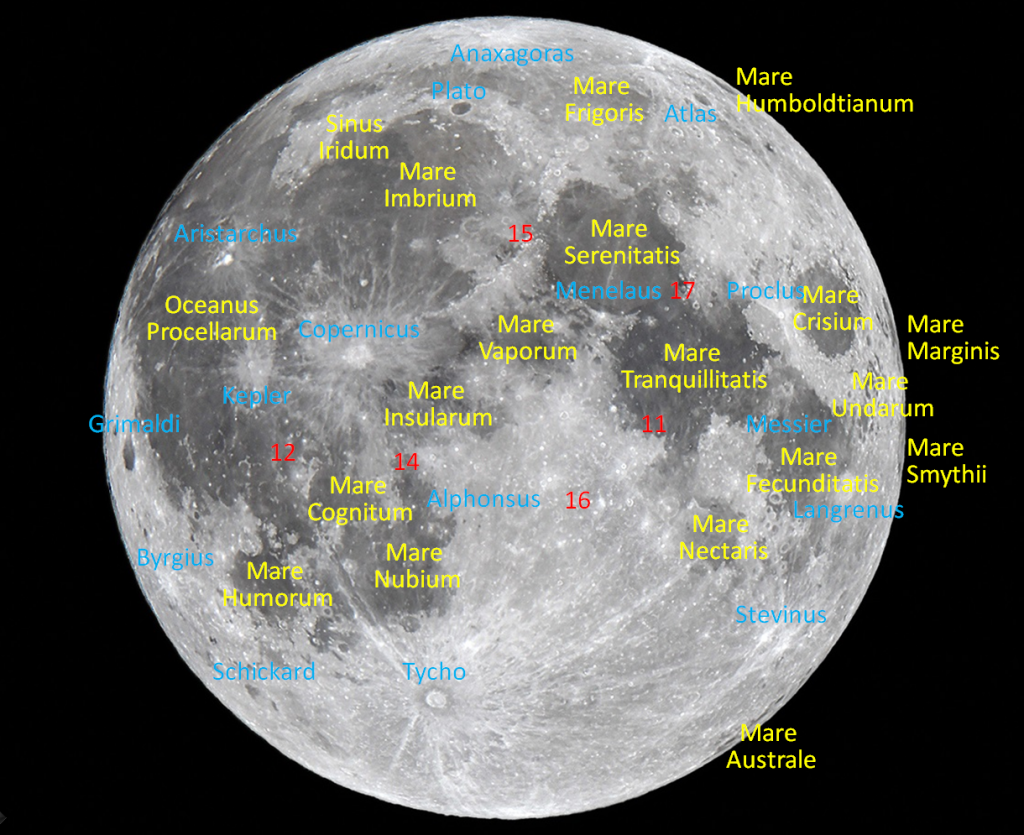

When you turn and face the nearly fully illuminated moon this week, the sunlight striking the moon will be coming from directly “behind you”, similar to the way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! At that time, you can easily distinguish the dark, grey, basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and later flooded with molten rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history. That filling happened in stages. A backyard telescope will easily reveal zones of lighter and darker basalt emplaced at different times, and terraces of lava that “froze” after each incursion. The subtle terraces are best seen when the moon isn’t full.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are also heavily cratered – because there has been no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of countless impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance of anorthosite is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of large crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material long distances on top of the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar rays systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones from the very bright, 100 million-year-old crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the moon this week. There are large and small ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters recently blasted into the maria have tossed dark rays onto white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock underneath it, a small telescope will show lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis the “Sea of Serenity”, where humankind first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. Sharp-eyes might detect that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to enrichment of the basalt by the metal titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent there.

Now that you know more of the lunar terminology, here are some additional things to watch for…

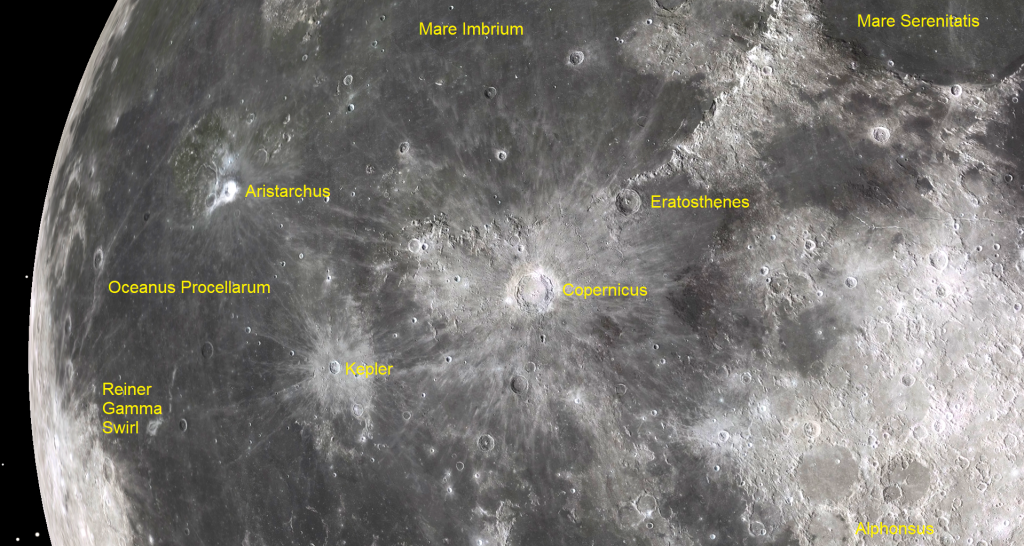

This middle of this week will also be ideal for viewing the prominent crater Copernicus in eastern Oceanus Procellarum, the “Ocean of Storms”, which is the large dark region located south of large Mare Imbrium. Copernicus is located slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. The Jesuit priest Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who published a labelled map of the moon in 1651, deliberately placed the craters named for astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, their defender Ismaël Bullialdus, and the Greek philosophers Aristarchus, Eratosthenes, and Seleucus, into the Ocean of Storms because they all dared to suggest that Earth revolved around the sun – in contravention to the church’s teachings at that time. Riccioli honoured his fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters elsewhere on the moon.

The 800 million year old crater Copernicus is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before and after the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus will exhibit heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ rather ragged ray system, which extends 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – caused by impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

The prominent crater Kepler is located to the lunar west of Copernicus. Smaller, but brighter Aristarchus is positioned north of them. It is one of the most colourful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon at Aristarchus.

The waning, but still bright and quite full, moon will spend Wednesday night near the Leo’s brightest star Regulus. That star’s name was used for a character in the Harry Potter series. Regulus is a hot, blue giant star located only 79 light-years from our sun. Binoculars or a telescope will reveal a small companion star close to it.

The moon will spend Thursday night in Leo and then celebrate Valentine’s Day by entering the territory of Virgo (the Maiden) on Friday. When the waning gibbous moon rises in late evening next Sunday, it will be shining to the upper right (or celestial west) of Virgo’s brightest star Spica. As the night wears on the moon will shift closer to the star while Earth’s rotation carries them west, where they will set after sunrise on Monday. Meanwhile, skywatchers in a zone stretching across the South Pacific Ocean can watch the moon occult Spica in the middle of the night.

The Planets

The tour of the sky’s bright planets and stars I shared last week here will still be valid this week. The “planet parade” or “planetary alignment” will become complete when Mercury rises to join the rest of the planets next week. Unfortunately, Saturn will be leaving soon.

The planet Venus alternates between morning and evening appearances every 584 days, or 1.6 Earth years. It stays around much longer than speedy Mercury does. Because we are viewing our sister planet from the moving platform of Earth, its apparitions, to use the astronomical term, are asymmetrical. Venus first enters the evening sky about 8 months before its greatest eastern elongation from the sun, and then it takes about 2.5 months to sink sunward again (the stage we’re in right now). For its morning appearances, Venus takes 2.5 months to reach its greatest western elongation away from the pre-dawn sun, and then 8 months to sink back into the predawn twilight – and so on. Venus will pass inferior solar conjunction, between Earth and the sun, on March 23. Then it will spend from April to mid-June increasing its distance from the morning sun.

Venus is bright enough to cast shadows on moonless nights and to be seen in daylight when it is high in the sky. It ranges in apparent brightness from magnitude -4.9 to -3.8, which is almost a factor of 3 difference. The sun and the moon are the only naturally brighter objects – unless a nearby star happens to go supernova one day. Venus’ extreme brilliance is mainly due to its proximity to Earth (as little as 41 million km) and to the high reflectivity of its cloud tops. Its variability comes from its change in distance from us combined with its change in illuminated phase.

Venus will continue to gleam in the southwestern sky from sunset until it drops into the trees with the surrounding stars of Pisces (the Fishes) around 8:15 pm local time. The Goddess of Love’s greatest illuminated extent happens to occur this week on Valentine’s Day! In a telescope, the planet will show a slim, 27%-illuminated, crescent phase and an apparent disk size of 39.3 arc-seconds. (For comparison, the full moon is about 1,900 arc-seconds across.)

Even with its less than fully-illuminated disk on display, Venus’ distance from Earth of only 0.425 Astronomical Units or 63.6 million km will boost its brightness to a brilliant peak magnitude of -4.85. Don’t fret if Friday is cloudy. Venus will appear just as bright for several evenings. To see the planet’s shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at Venus while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened. Good binoculars can hint at Venus’ non-round shape, too.

We’re past the time when we see Saturn clearly through a telescope, but the medium-bright planet’s yellowish dot can still be spotted shining less than two fist diameters below Venus as the sky darkens after sunset this week. You may need to walk around a bit to find it between the trees or buildings. Next week, Saturn will start to be overwhelmed in a bright twilit sky. The faint, distant planet Neptune will be positioned between Saturn and Venus.

Though not as bright as Venus, Jupiter will gleam high in the southeastern sky at dusk every night. It will climb highest, due south, at about 7:30 pm local time, and then set during the wee hours. This month, Jupiter is positioned above the triangular group of stars that form the face of Taurus (the Bull). Taurus’ brightest star, noticeably reddish Aldebaran marks the eye of the beast below Jupiter. You could mistake it for Mars.

Viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a large disk striped with brown dark belts and creamy light zones, both aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, and also after 10 pm Eastern time tonight (Sunday), Wednesday, Friday, and late next Sunday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All four moons will gather to one side on Wednesday.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Europa’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter’s mid-southern latitudes on Friday morning, February 15 between 12:08 am and 2:39 am EST (or 05:08 to 07:39 GMT on Saturday). Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter on Saturday evening, February 15 between 11:42 pm and 1:52 am EST (or 04:42 to 06:52 GMT on Sunday).

The distant ice giant planet Uranus, which is near Jupiter and the Pleiades this year, will be observable from the end of evening twilight until beyond midnight every night. If you use your binoculars to find the medium-bright stars named Botein and Epsilon Arietis, Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths to the left (or southeast of) them. In a backyard telescope, it will appear as a fairly prominent, non-twinkling blue-green dot.

Closing off our parade, the bright reddish planet Mars will climb the eastern evening sky this week, forming a triangle to the right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s bright stars Pollux and Castor. Mars will be highest due south at 10:15 pm local time and set in the northwest before sunrise. Don’t forget that the bright moon will crash their party tonight only (Sunday). At 109 million km away and receding every night, Mars is still close enough to Earth to show us its bright polar cap and dark patches on its small rusty globe when viewed through a good backyard telescope.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!