Venus Descends the Pre-Dawn Sky, Spectacular Sights on the Full Corn Moon, Our Moon Mambos with Mars while Jupiter’s Moons Play Hide and Seek!

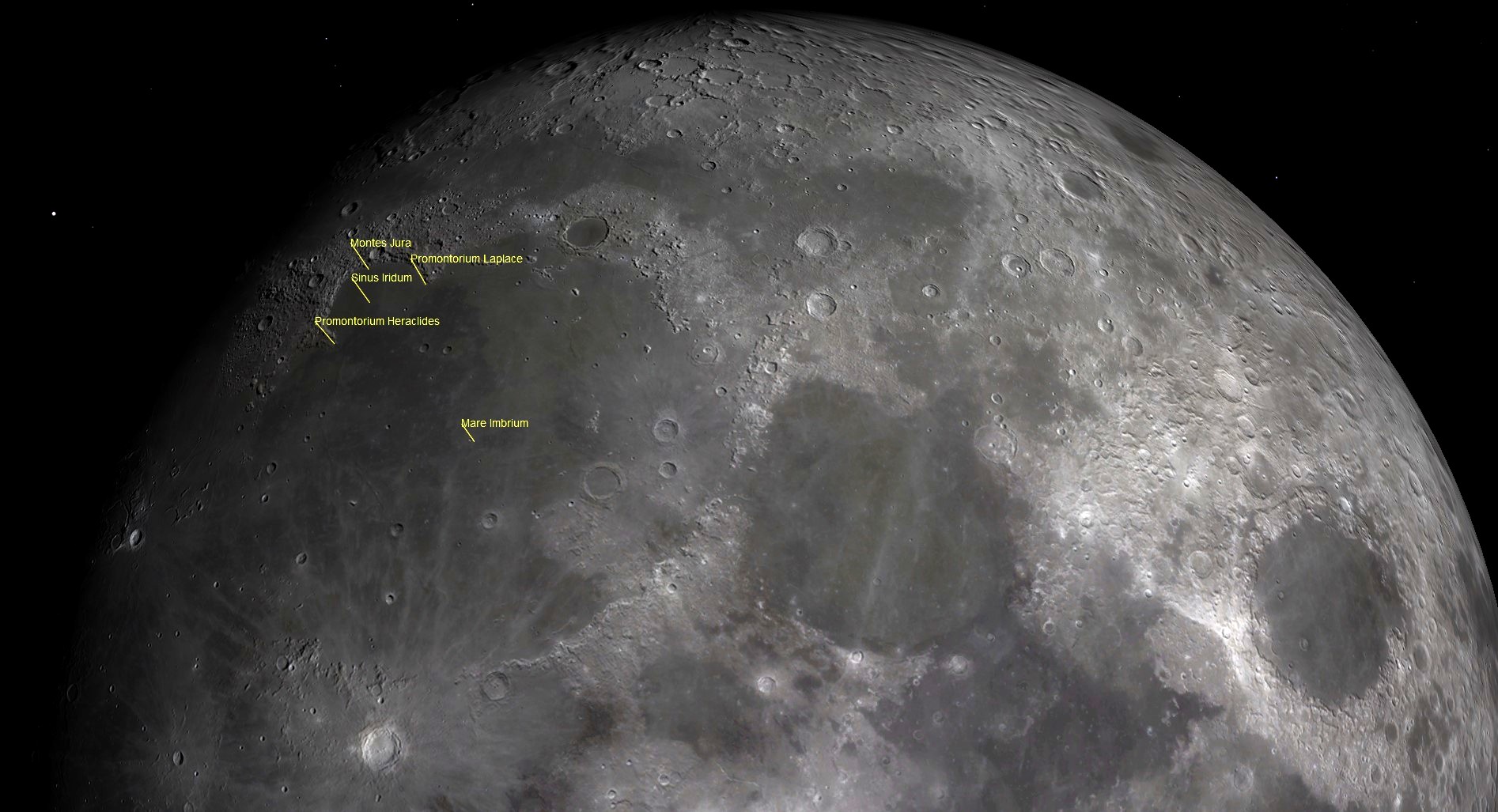

This simulated view of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows, and the Golden Handle that envelops its western perimeter, was made using Starry Night software. Every month, a few days before full moon, the handle effect is visible with sharp, unaided eyes, and very easily through binoculars and backyard telescopes. The latter might also reveal the N-S aligned dorsae, or wrinkle ridges on the floor of the otherwise craterless sinus.

Hello, Late-Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 30th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will shine brightly at night around the world this week as it reaches, and then passes, its full phase. So I’ve highlighted some of its best sights. Meanwhile, Jupiter and Saturn – and later, Mars – will gleam in the evening sky, and Venus will do the same in the east before dawn. It’s fun to watch the antics of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, and I’ve noted some. Here are your Skylights!

The Moon

The bright moon will dominate night skies all around the world this week – so I’ll highlight some sights to see on it!

The terminator is the curved, pole-to-pole boundary that divides the moon’s lit hemisphere from its dark hemisphere. Every solid object in space that is being lit by sunlight has a terminator. The terminator’s appearance can tell us the form of an object – even from a great distance away! Astronomers of old deduced that the moon was spherical by noting that the terminator was curved during the crescent and gibbous phases of the moon, and it was a straight line at first and last quarter. You can replicate the effect by shining a light on a ball in a dark room. As you move the light around, you can replicate the phases of the moon and make the terminator curved or straight. If an object has a more complicated shape, such as a potato, or a comet or asteroid, the terminator will be more complicated where it crosses the deformities. (We use the same technique to create 3D models of solid objects by scanning a straight laser beam across them.)

Tonight (Sunday), the terminator on the waxing gibbous moon will fall just to the lunar west of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows (sinus is Latin for “bay” – as in sinusoidal). The circular 249 km-diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same dark, iron-rich basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its east – forming a rounded handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. Look for the feature in the upper left region of the moon – with your unaided eyes, or with binoculars – then zoom in with your telescope. (If you live south of the equator, the feature will show near the bottom of the moon.)

Sinus Iridum is famous for a “Golden Handle” effect that is obvious around this phase of the moon. It’s produced when slanted sunlight brightly illuminates the eastern side of a prominent, curved mountain range called Montes Jura that surrounds the bay on the north and west – and by a pair of promontories named Heraclides (on the south) and Laplace (on the north) that protrude into it. The mountains are actually the partial edge of the old crater. Viewed in a telescope, Sinus Iridum itself is almost craterless, but it hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed at this phase. You can look at Sinus Iridum on any night this week – but it may not be as impressive.

Due to its orbital inclination and ellipticity, the moon tilts up-and-down and sways left-to-right by a small amount while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth at all times. Over the course of many months, this lunar libration effect lets us see 56% of the moon’s total surface from Earth. The motions can be detected by noting the positions of major features near the limb of the moon. One of the best of these is dark and very round Mare Crisium, the Sea of Crises. The 556 km-wide basin is easy to see using your unaided eyes or binoculars – and in telescopes. It always sits in the northeastern quadrant of the moon – that’s the upper right for Northern Hemisphere observers (lunar east is the opposite of sky east). Keep an eye on Mare Crisium over the next few months and note how it shifts towards and away from the moon’s edge while also riding higher and lower.

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain of darker rock across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humankind first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. Notice that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to enrichment in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons the first Apollo mission was sent there – geologists wanted to know why it was so different.

Near the full moon phase, bright rays can be seen extending from the younger craters on the lunar near side. The impact that created the bright crater Tycho, which is located in the south-central area of the moon, threw out streaks of bright material that extend thousands of km in all directions across the moon’s near side. Another particularly interesting ray system surrounds the crater Proclus. The 28 km-wide crater and its ray system are visible in binoculars and telescopes, at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium. The Proclus rays, about 600 km in length, only exist on the eastern, right-hand side of the crater, and also within Mare Crisium, suggesting that the object that produced them arrived at a very shallow angle from the southwest.

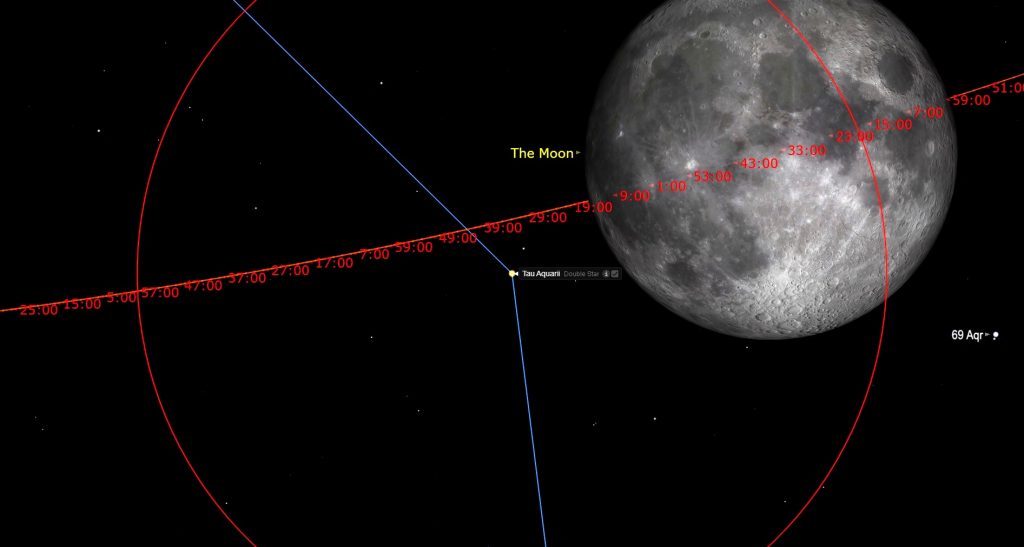

In the eastern evening sky on Tuesday, observers using binoculars and backyard telescopes in the eastern half of North America can see the almost-full moon pass in front of (or occult) the medium-bright (magnitude 4.05) star designated Tau Aquarii or τ Aqr or 71 Aquarii. That star marks the right (western) knee of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). In the Great Lakes region, the left-hand edge of the moon will cover the star at approximately 9:55 pm EDT (or 01:55 Greenwich Mean Time on Wednesday). The star will re-appear from behind the opposite limb of the moon at about 11:13 pm EDT (03:13 UT). Ingress and egress times vary based on your latitude, so start watching a few minutes before the times quoted above – or use Stellarium or an astronomy app to look up the exact times for your location.

The September full moon will occur on Wednesday morning at 1:22 am EDT, or 5:22 Greenwich Mean Time. Traditionally known as the “Corn Moon” and “Barley Moon”, this one always shines in or near the stars of Aquarius and Pisces. In North American Ojibwe indigenous traditions, this moon is Biinaakwe Giizis, “Falling Leaves Moon”. The Cree call it Nimitahamowipisim, “Rutting Moon” – when the bull moose scrapes the velvet from his antlers as a sign that mating shall begin. In most years, the September full moon is also the Harvest Moon. But October’s full moon will be the one happening closest to the equinox in 2020 – so it will have that honor. Since the full phase will officially occur in the wee hours of Wednesday in the Americas, the moon will already look full when it rises there a few hours earlier, on Tuesday evening. Only in the central Pacific Ocean region will the moon be precisely full when it rises at sunset.

From Wednesday night onward, the moon will rise later and later and wane in phase. Every night, it will shift eastward through the constellations of Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale). The moon rising later also means that the moon will set later – allowing us to see it in the early morning daytime sky on the coming weekend.

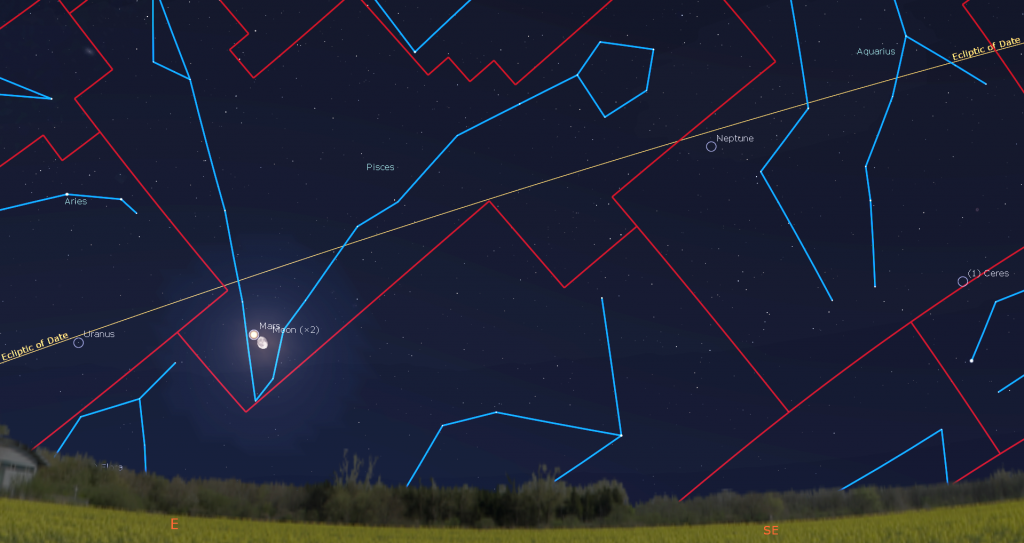

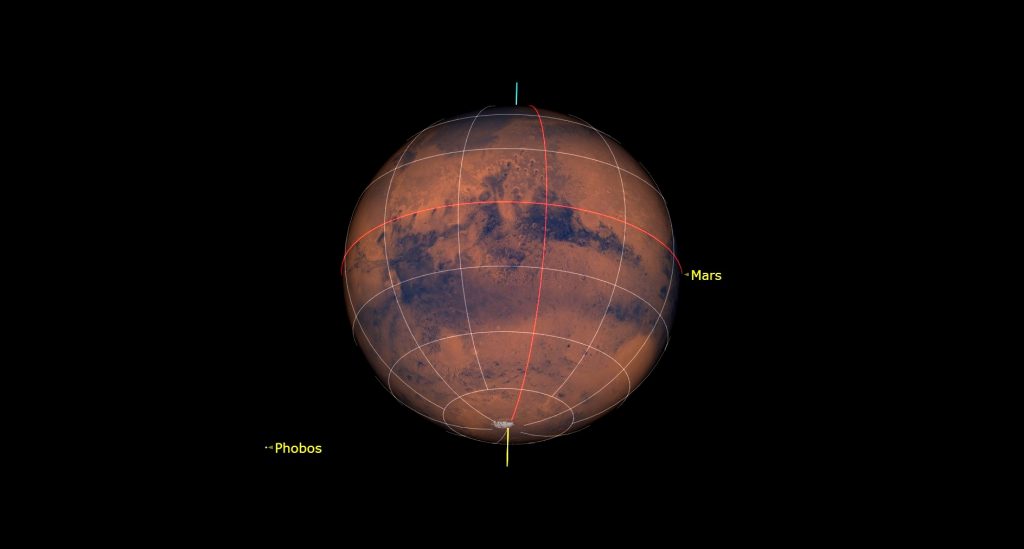

Saturday brings a treat! When the bright, waning gibbous moon rises in the east at about 9:45 pm local time on Saturday, it will be positioned only a finger’s width below (or 1 degree to the celestial southwest of) Mars! That’s close enough to appear together in binoculars and in the eyepiece of your telescope at low magnification. As the duo crosses the sky together during the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky, and the moon’s eastward orbital motion, will combine to shift the moon clockwise around Mars – placing it above the planet by sunrise on Sunday morning. Since the pair will not set in the west until mid-morning on the 6th – skywatchers have a chance to see Mars in the morning daytime sky using binoculars and backyard telescopes – by using the moon as a reference. They’ll be so close together that observers in central and northeastern South America, Cape Verde Islands, northern Africa, and southern Europe can see the moon occult Mars around 05:00 GMT on Sunday!

Finally – when the bright, waning gibbous moon rises in the east at about 10 pm local time on Sunday, September 6, it will be positioned a few finger widths below (or 4 degrees to the celestial south of) blue-green Uranus. That magnitude 5.71 planet is usually visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes – if you know where to find it. This bright moon will be too bright for dim-planet hunting, though. Note the positions of the brighter stars in Cetus (below the moon) and Aries (above Uranus), and use them to find Uranus on a night when the moon isn’t nearby.

The Planets

Speedy little Mercury will be visible in the west-northwestern post-sunset sky this week – but the low angle of the evening ecliptic will keep it very close to the horizon for everyone living at mid-northern latitudes. If you’re game to look for it, the best time window is around 8 pm local time. If you live near the equator, or in the Southern Hemisphere, Mercury will put on a great show for you in September!

Once the sky darkens after sunset, very bright, white Jupiter will pop into view first. It’s low in the southeastern sky – with dimmer, yellowish Saturn positioned less than a fist’s diameter to its left (east). Good binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. Even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short) – if the air is steady. Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour period of rotation, the GRS appears every second or third night from any given location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk on Thursday and Saturday. It will also be visible starting in late evening on Monday and Wednesday.

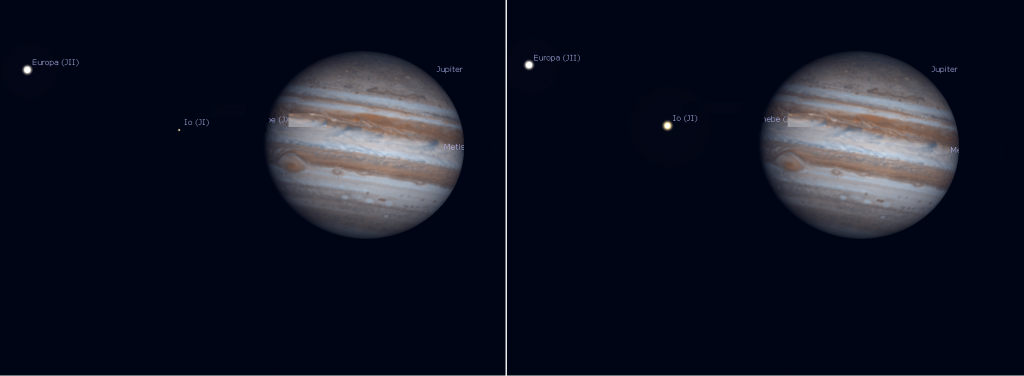

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. Commencing at 10:28 pm EDT on Sunday evening, August 30, Io’s shadow will travel across Jupiter until 12:44 am EDT.

At 9:52 pm EDT on Monday night, you can see Jupiter’s moon Io pop into view when it moves out of Jupiter’s shadow to the east (left) of the planet. Over the course of a couple of minutes, Jupiter will change from having three visible moons, to four! On Tuesday at 8:33 pm EDT, Ganymede will disappear when it enters Jupiter’s shadow to the east (left) of the planet. On Saturday night at 11:58 pm EDT, Callisto will pop into view.

Technically, these events are eclipses – when one object (in this case, Jupiter) prevents the sun’s light from reaching another object (a moon). Strong binoculars can be used to see these events, but any sized telescope will work better. In each case, start watching a few minutes beforehand, and remember that your telescope might flip the view around. The events will be visible anywhere on Earth where Jupiter is well above the horizon in a dark sky at the times I’ve given. Just convert from Eastern time to your own time zone.

Saturn is a spectacular sight in backyard telescopes. With your unaided eyes, you should be able to see it sitting to much brighter Jupiter’s left by about 9 pm local time. Even a small backyard telescope will show Saturn’s rings. They’ll be getting narrower every year – until they vanish for a few weeks during the spring of 2025. In the telescope, the rings are almost as almost as wide as Jupiter’s disk. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

A small telescope will also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the lower left of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.)

Reddish Mars is steadily increasing in disk size and brightness recently because Earth is travelling towards it until October 6. Mars will put on a great sky show this autumn – but we don’t have to wait until then for good views of it! I’ve already seen its southern polar cap quite clearly in my small telescope. This week, the Red Planet will be rising in the east just before 10 pm in your local time zone. Then it will cross the sky until dawn, when it will be positioned about five fist diameters above the southwestern horizon. Nothing near Mars is as bright, nor as red! Due to its orbital motion combined with ours, Mars has been speeding along the ecliptic. But now it’s slowing down as it prepares to start a retrograde loop next week. This week, Mars will continue to shift eastward (right-to-left) in the narrow “V” of modest stars at the bottom of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes).

On Thursday, September 3, the southern polar axis of Mars will reach its maximum tilt of 24 degrees towards the sun, triggering the solstice, and the beginning of winter in Mars’ Northern Hemisphere. Mars’ longer year means that its seasons are longer, too – slightly more than five months. Viewed in amateur telescopes from our vantage point on Earth, Mars’ southern polar cap will shine as a bright, white spot on the red planet (although your telescope’s optics may flip Mars over).

This week blue-green Uranus will rise before 10:30 pm local time and sit a generous fist’s diameter to the lower left (or 14° to the celestial east) of much brighter Mars. Dim and distant Neptune is located among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) – almost four fist diameters to the right (or 37° to the celestial west) of Mars. This week, Neptune will be rising soon after 8 pm local time. Then it will climb higher until about 2 am local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s halfway up the southern sky. This week’s moon-filled sky is a not good time to search for those two planets, though.

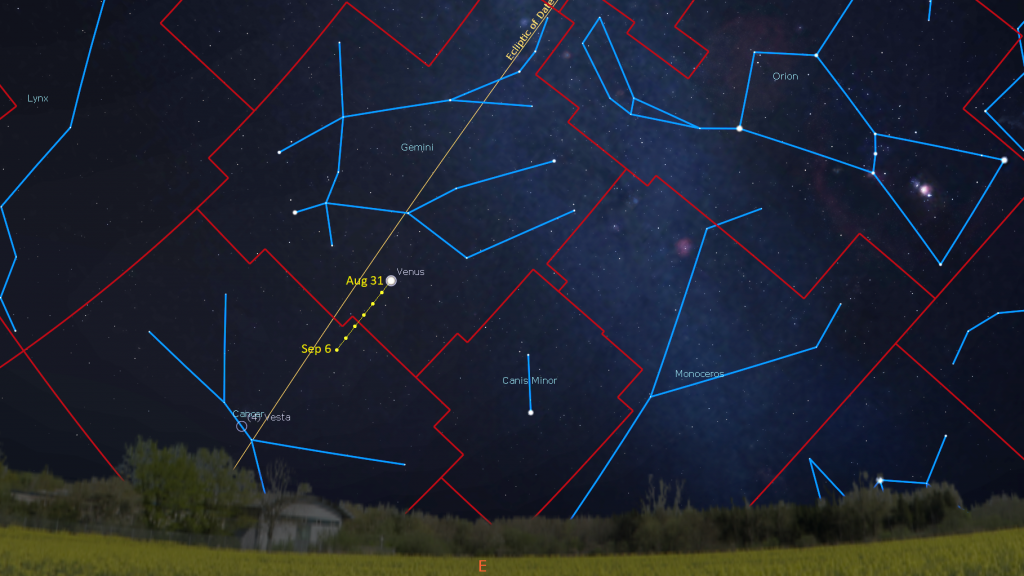

Extremely bright Venus will rise in the east-northeast at about 3 am local time this week, and then remain visible until sunrise as it is carried higher in the eastern sky by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a half-illuminated shape. The planet will travel east between Gemini (the Twins) and Cancer (the Crab). Venus is now shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will let it shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until early December! And while you’re up, enjoy a view of Orion (the Hunter) sitting well off to Venus’ right.

Bright Stars Roundup

If you missed last week’s tour of the bright stars visible on moon-filled evenings, I posted it with sky charts here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, September 6, when we’ll celebrate the big Mars Opposition this October. Details and the schedule are here. In the meantime, join Jenna and John Reid on alternate Thursdays at 3:30 pm EDT as they run through the RASC’s Explore the Universe certificate.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!