Venus in Morning, New Luna Partly Eclipses Sol, Leo Leads to Galaxies, and Messier Marathon Attempt Two!

Meteorologist, pilot, and astro-imager Kerry-Ann Lecky Hepburn captured this amazing shot of the August, 2017 partial solar eclipse behind Toronto’s CN Tower from Saint Catharine’s, Ontario. See more of her work at www.weatherandsky.com

Hello, Late-March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 23rd, 2025 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on FaceBook, Instagram, Threads, and Bluesky as astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

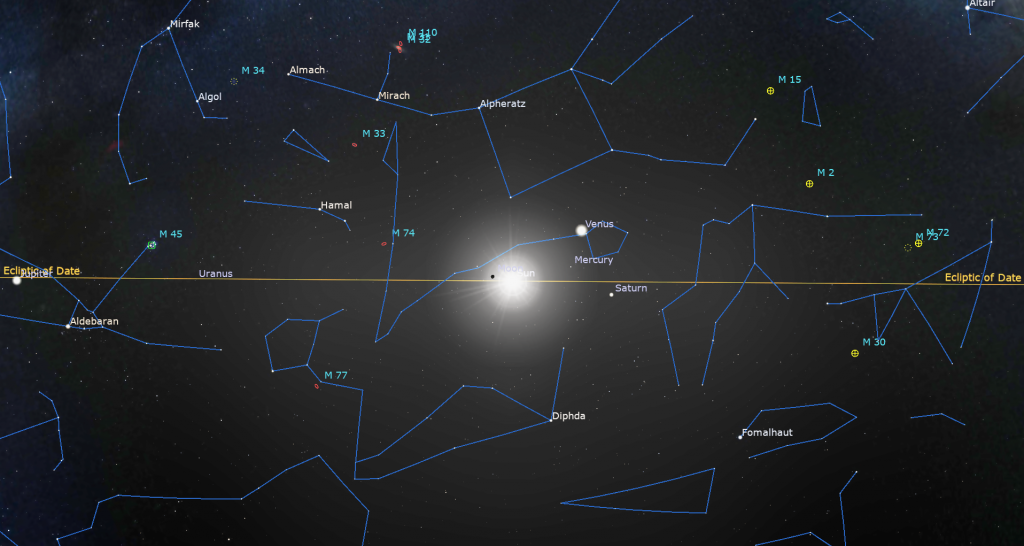

The moon will pass close enough to the sun at new moon on Saturday to generate a partial solar eclipse that will be visible from eastern Canada and the northeast USA across the North Atlantic to northwestern Europe! Temporarily ringless Saturn has moved to the eastern pre-dawn sky with Venus, Mercury, and Neptune, leaving only Uranus, Jupiter, and Mars in evening. The moonless nights will be ideal for exploring the sights in Leo and for attempting a Messier Marathon. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon Meets the Sun

This week will be the part of the moon’s 29.5 day cycle when it approaches and passes the sun at new moon. That will deliver moonless nights for stargazers worldwide – hooray!

Since the moon will be rising in the east before the sun does, we can only see our natural satellite if we head outside before sunrise on Monday and Tuesday, when it will be rising more than 90 minutes before the sun does. If you live closer to the equator, where the ecliptic and the moon’s orbit will be nearly vertical at sunrise, you’ll be able to glimpse the moon’s increasingly thin crescent until Friday morning. Then it will pass the sun at official new moon on Saturday morning at 6:58 am EDT, 3:58 am PDT, and 10:58 Greenwich Mean Time and re-appear in the western sky after sunset next Sunday evening.

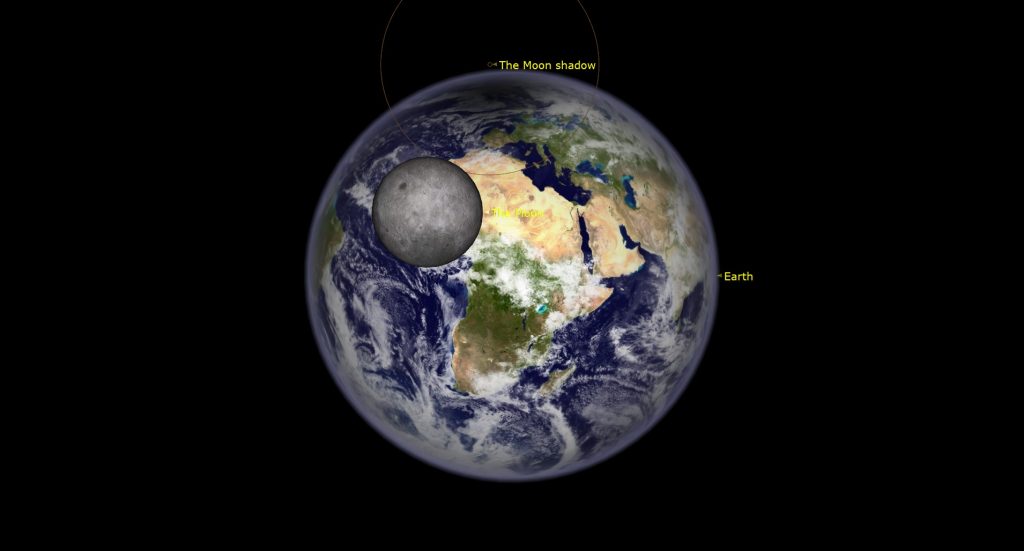

Normally, the moon is hidden from view for a day or two while it passes the sun, but Saturday morning’s new moon will also produce a very deep partial solar eclipse that is visible across the northeastern USA and Canada, Greenland, most of Europe, northwestern Africa, and northern Russia. This solar eclipse is the partner to the total lunar eclipse we saw two weeks ago. The moon is still close enough to the ecliptic to block part of the sun at new moon.

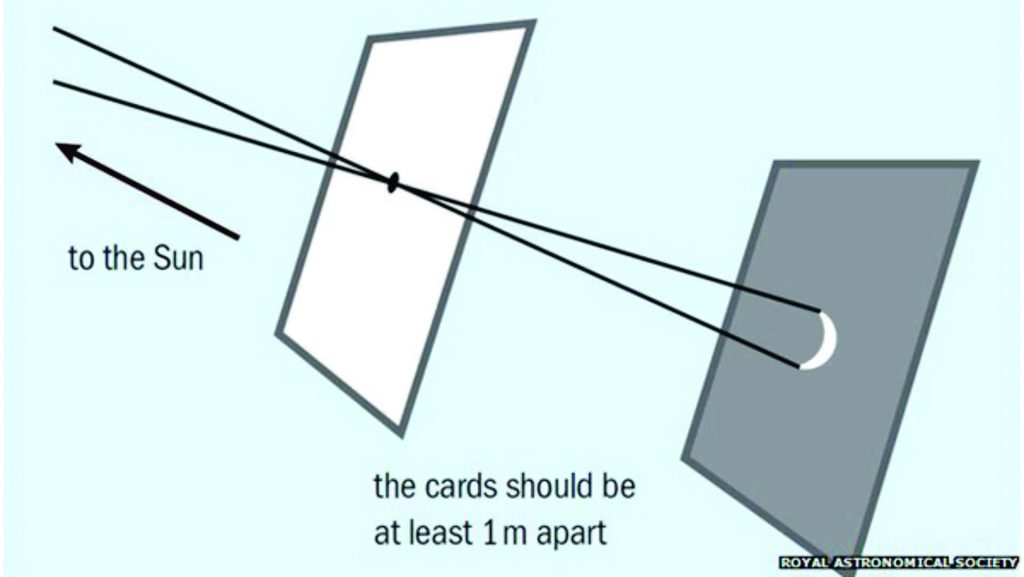

Unlike lunar eclipses, it is NEVER safe to look up at any exposed sun without a proper solar filter. During a partial solar eclipse, a part of the Sun’s disk is always exposed, and any amount of unprotected viewing is harmful to your eyes. Sunglasses are NOT enough to protect your eyes. They may make the sunlight dim enough to seem comfortable, but they do not filter out the harmful invisible ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) radiation that damages eye tissue. Your retinas do not have pain receptors that will alert you to the damage you’re doing to them.

Safe methods of observing solar eclipses include wearing special eclipse glasses (commonly inserted into astronomy magazines published prior to major eclipses or handed out by libraries, science centres and museums, and astronomy organizations), #14 or darker welder’s glass, pinhole projection setups, and special telescope filters. NEVER pass unfiltered sunlight through a telescope or binoculars. Damage to vision will be instantaneous, the equipment will likely suffer damage, and there is risk of fire, too. Direct sunlight can also damage your phone or DSLR camera.

A partial solar eclipse does not have the narrow total eclipse path where the moon completely covers the sun for a few minutes – so no glorious corona, Baily’s Beads and Diamond Ring effects, no 360° sunset and minutes of dark sky. Instead, a broad region on the Earth will be able to see the moon moving across part of the sun for about 90 minutes. Here are the details, courtesy of Mr. Eclipse, Fred Espenak. Visit https://www.eclipsewise.com/solar/SEgmapx/2001-2100/SE2025Mar29Pgmapx.html

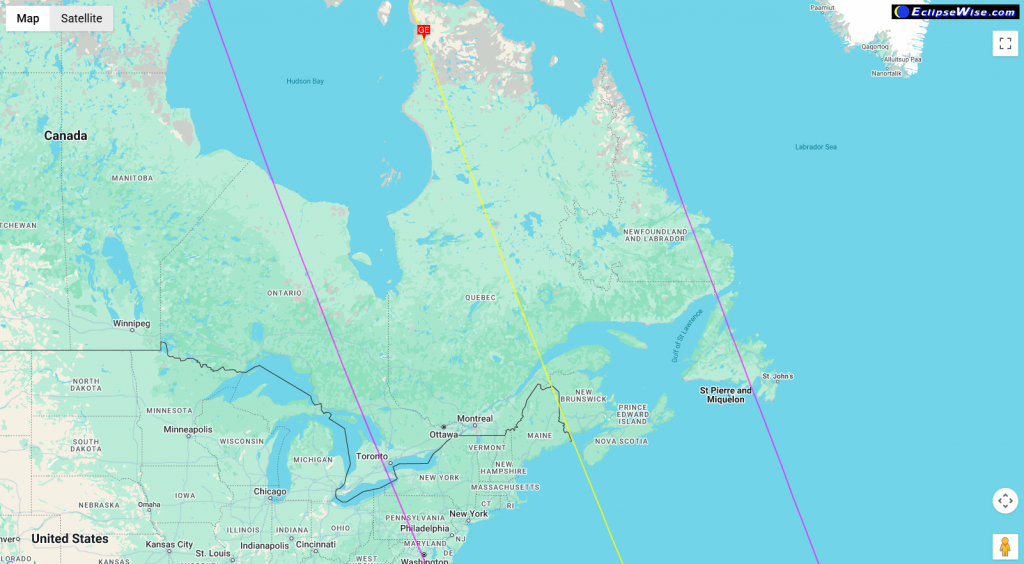

The first “bite” out of the edge of the sun will be evident when the moon’s penumbral shadow first contacts Earth at 08:50:43 GMT in the Atlantic Ocean north of Belem, Brazil, it will sweep northwestward through the New England states and the Canadian Maritimes, across Quebec and Nunavut, then over the pole and southward through northern Russia until it lifts off Earth north of Krasnoyarsk at 12:43:45 GMT. The instant of greatest eclipse, with the moon blocking 94% of the sun’s diameter, will occur on the northeastern coast of Hudson Bay, Canada just after sunrise at 6:47 am EDT or 10:47:27 GMT.

On the line extending north from St. Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean, to Virginia Beach, Virginia, Washington, DC, Mississauga, Ontario, Sudbury, Ontario and on to Rankin Inlet, the eclipse will be ending just as the sun rises. Use filters to look right away for a small bite out of the sun’s left limb.

Observers located farther east from there will see the sun more and more covered by the moon when they rise together. Lucky people who view the eclipse anywhere on the line from the western tip of Nova Scotia north through western New Brunswick, eastern Maine, the Rimouski region of Quebec, and north to Ivujivk, will see the moon will cover its maximum amount of the sun – anywhere between 85% and 94% of the sun’s diameter. The farther east from there you are, the higher in the sky the sun and moon will be, but the maximum amount of the sun eclipsed will be reduced. Observers in sunny Senegal, Mauritania, western Algeria and Tunisia will see only a tiny amount of the sun’s right limb “bitten” for a few minutes in late morning. That limit line extends northeast from Tunis, through Belgrade, Serbia, Kyiv, Ukraine, and beyond into northeastern Russia.

Several groups will livestream the eclipse, including on YouTube and on Timeanddate.com, https://www.timeanddate.com/live/. You can preview the visibility of any eclipse with the free Stellarium program or app by adjusting the date and time at your location. You might need to switch to a flat landscape if the eclipse occurs near sunrise or sunset. Current versions of Stellarium also include a tool that shows the maximum eclipse appearance for any location. Click the Astronomical Calculations Window [F10], and then the Eclipses tab, and then the Calculate Eclipses button at lower right. Then double-click an entry and it will show you the sky where the eclipse will be seen at its maximum.

Messier Marathon Take Two

A month ago, I shared information here about carrying out a Messier Marathon. During the new moon periods in early spring each year, it’s possible for lovers of deep sky objects (nebulae, galaxies, and clusters) who live anywhere on Earth between latitudes 20° south and 55° north to observe every one of the 110 objects on Charles Messier’s list within a single night using a backyard telescope. For many amateur astronomers, this observing challenge is a bucket list item.

Last month’s chance was cloudy here in the Great Lakes region. Our second and final opportunity arrives this weekend. If the sky is clear all night long, we can start by viewing the galaxies M74 and M77 above the western horizon immediately after dusk and cross the finish line with the globular star cluster M30 just before sunrise. Actually, that one will be really tough to see in a brightening sky, but who’s counting? Clear skies!

Earth on Saturn’s Ring Plane

This morning, Sunday, March 23, the dance of Saturn and Earth in their orbits will carried us from the north side to the south side of the plane defined by Saturn’s rings, an event that happens every fourteen to seventeen Earth years. Today, the planet’s very thin rings will effectively vanish from view for a number of hours, leaving the planet as a simple, unadorned globe, like Jupiter. I posted a simulated view of Saturn here.

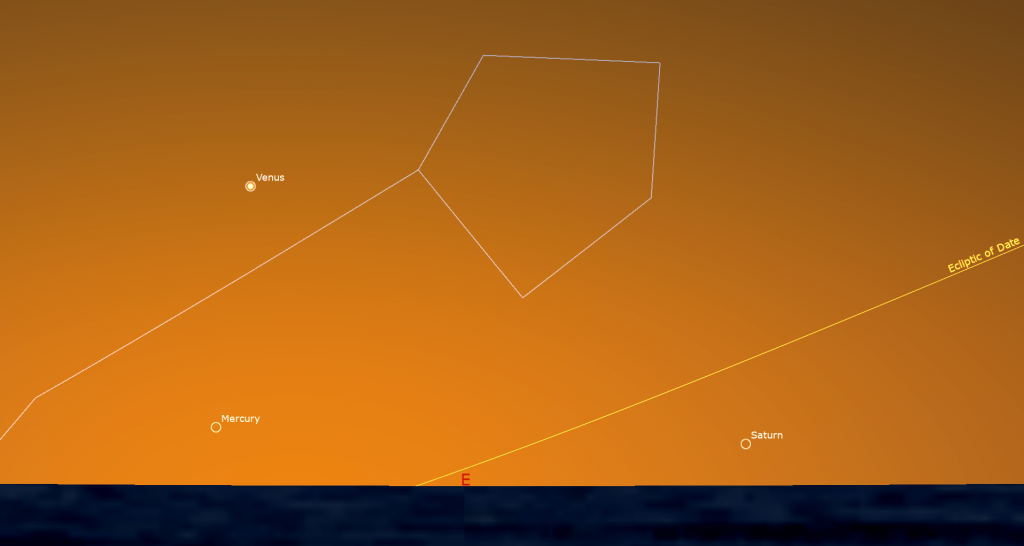

During the weeks surrounding the crossing, the rings appear through backyard telescopes as a thin line drawn through Saturn. Unfortunately, this crossing occurred while Saturn was only 10 degrees from the pre-dawn sun and positioned just above the horizon for observers at mid-northern latitudes. Hopefully, the people viewing Saturn from mid-southern latitudes got some photos of the planet without its iconic rings, despite the morning twilight and atmospheric turbulence and haze over the eastern horizon.

For the rest of this year, the rings will appear very thin. They’ll eventually open to their maximum width again in May, 2032. The next ring plane crossing will be in October, 2038, when Saturn will be easy to see while it’s a substantial 28 degrees from the morning sun. Mark your calendars!

The Planets

With the departure of Venus, Mercury, Neptune, and Saturn from the western sky, we are left with only three planets to see in the evening worldwide. Over the coming weeks, those four planets will gradually climb free of the twilit eastern sky before sunrise, but the sloping morning ecliptic will prevent mid-Northern latitude planet-lovers from seeing them shining higher, and in a darker pre-dawn sky, until mid-May. If you are out early this week and have a clear sky to the east, you might already spot brilliant Venus just above the eastern horizon before sunrise. Turn all optics away from the east before the sun begins to appear.

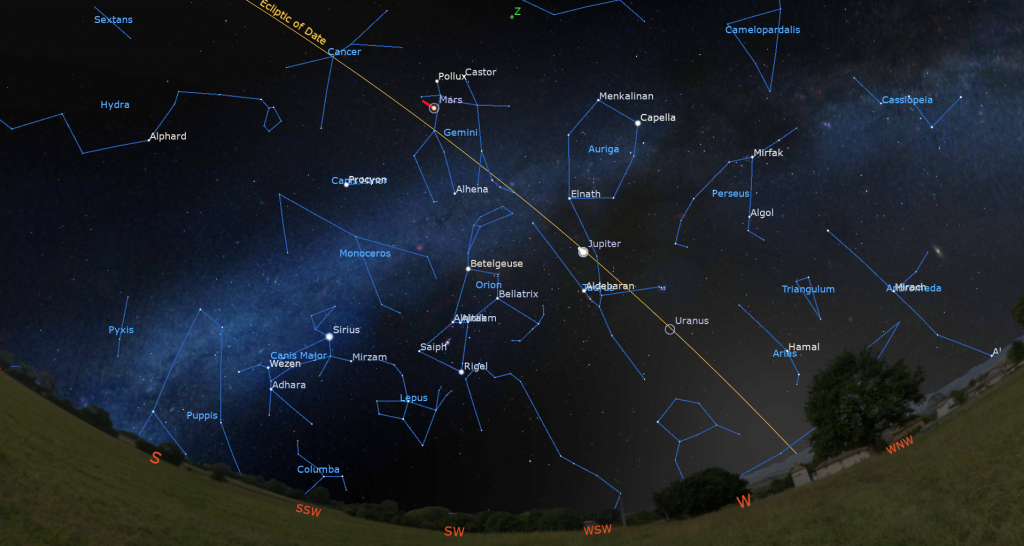

The very bright planet Jupiter will become visible about halfway up the western sky once it starts to darken after sunset. Before long, the brightest stars of winter will appear around Jupiter. The bright, reddish star just below Jupiter will be Aldebaran, a red giant star that marks the left eye of Taurus (the Bull). Over the next month, Jupiter’s easterly prograde motion will carry it higher above Aldebaran and between the beast’s horns. At the same time, Earth’s orbit around the sun will carry the stars down and sunward, so that, a month from now, Jupiter will be getting too low for crisp views in a telescope by the time you can find it. We’ll continue to see its bright dot descending the western sky until the end of May. This week, Jupiter will drop into the treetops around midnight local time.

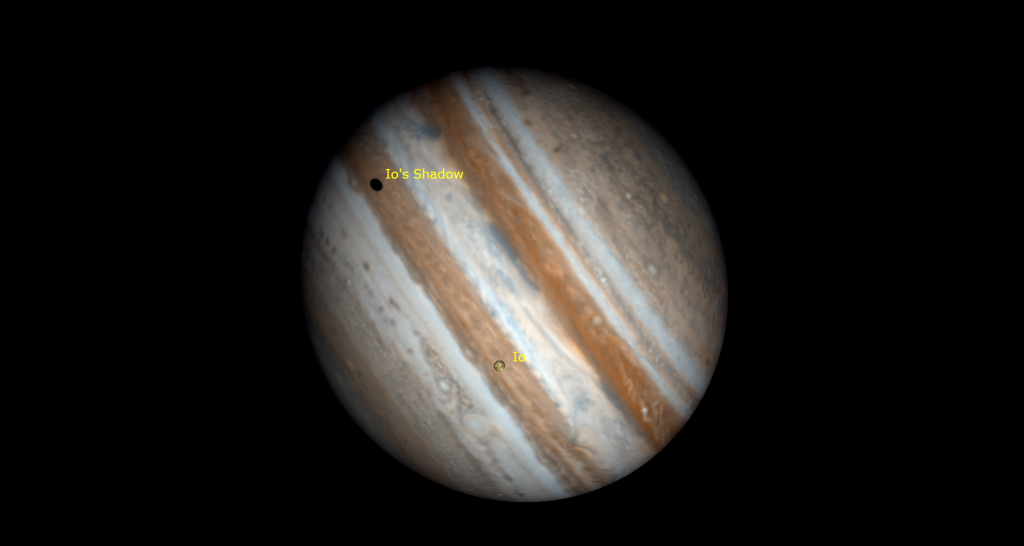

For now, when viewed in any size of telescope, Jupiter will display a large disk striped with several dark brown belts and beige light zones, all aligned parallel to its equator, which will be tilted as it sets. With a better grade of telescope, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, will be visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday, and also around 11 pm Eastern time on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Any size of binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. The moons will huddle in tightly spaced pairs flanking Jupiter tonight (Sunday), and will all gather all to one side of the planet on Monday.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter on Wednesday evening, March 26 between 11:18 pm and 1:29 am EDT (or 03:18 to 05:29 GMT on Thursday). Additional shadow crossings will be visible in other time zones.

Swinging our attention back to Aldebaran, search a generous fist’s width to its right, and down a little, for the bright little Pleiades Star Cluster (aka Messier 45, the Seven Sisters, Subaru, Matariki, and Bagonegiizhig). The stars look terrific in binoculars. Now sweep a palm’s width down to find Uranus. With the moon out of the sky, Uranus will be observable from the end of evening twilight until about 11 pm, when it will be hitting the treetops in the west. Uranus can be seen with unaided eyes if you know where to look. If you use your binoculars to find the up-down pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (aka Epsilon Arietis), Uranus will be the dull-looking blue-green “star” located several finger widths to their left (or southeast). In a backyard telescope, Uranus will appear as a fairly prominent, non-twinkling blue-green dot.

Mars, being a tenth as bright as Jupiter, will need the sky to darken quite a bit before you can find it shining very high in the southern sky below two bright stars representing the brothers Pollux and Castor in Gemini (the Twins). Due to Mars’ eastward prograde orbital motion, the triangle that Mars is forming with those stars will gradually become a line during the next two weeks.

You have plenty of time to view Mars every night, since it won’t set in the west until 4:30 am local time. Our 159 million km distance from Mars is increasing daily, so the planet is steadily shrinking in apparent size and losing its brilliance. Your good quality backyard telescope might still show its bright polar cap, some dark patches on its small reddish globe, and the fact that it now has a gibbous, 91%-illuminated disk. We’ll continue to see Mars as a bright dot until late July, but do your close-up viewing of it sooner than later.

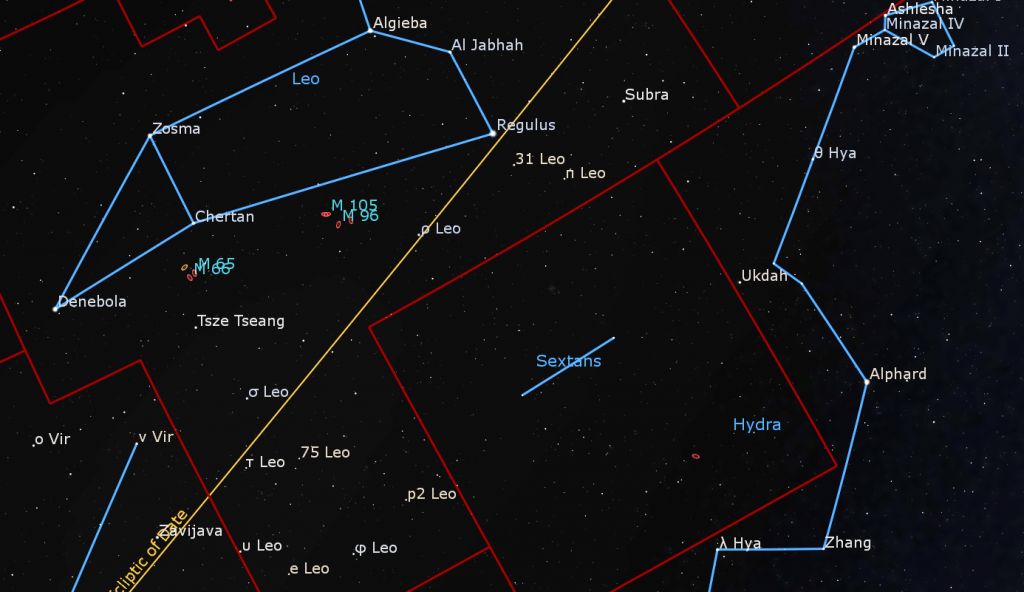

Leo Leads to Galaxies

The bright moon’s departure from the evening sky worldwide this week will officially open galaxy-viewing season! That’s a two month window when the Milky Way drops to the horizon, leaving the evening sky overhead free of its obscuring gas and dust, and letting us peer into the deep Universe at the other galaxies there! On the dates when the moon is close to the daytime sun or rises after midnight, we are treated to especially dark skies for hunting these faint, but majestic objects. This year, those blocks of time are now to March 31 and again from to April 20 to 29. Plan your cottage and camping visits with that in mind!

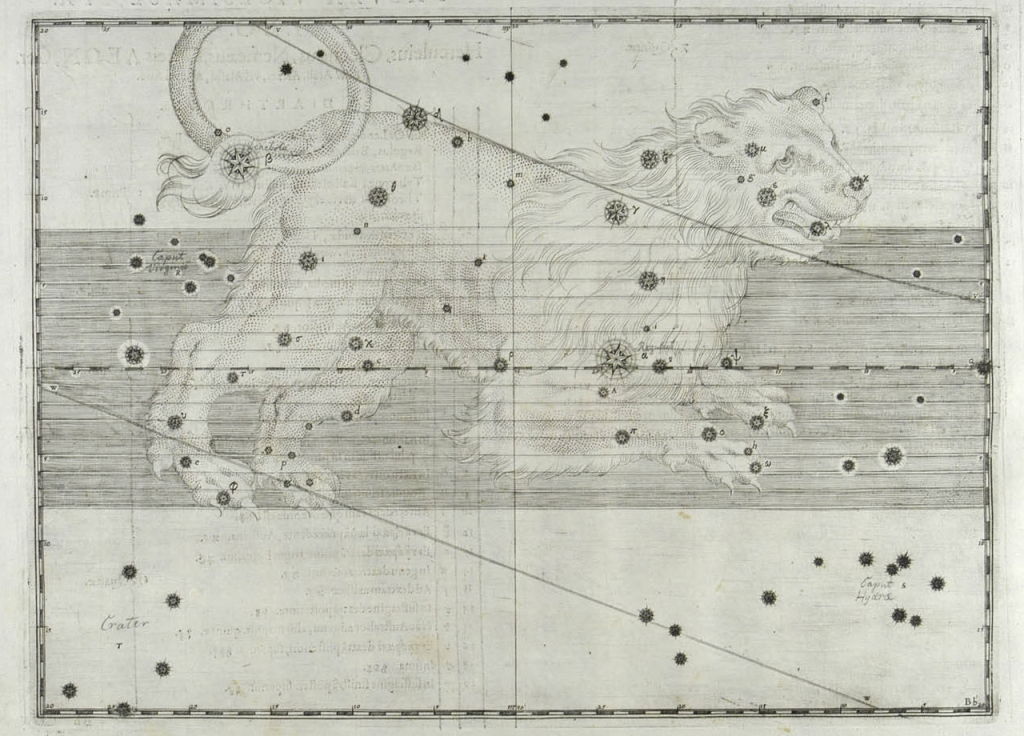

The richest repository of springtime galaxies is between the constellations of Leo (the Lion) and Virgo (the Maiden), and the constellations above them, Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair), Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs), and Ursa Major (the Big Bear). That’s because the North Galactic Pole, the spot on the celestial sphere that points vertically out of our Milky Way galaxy’s disk, is located in Coma Berenices. To help you find and view some of those galaxies, let me introduce you to an easy guide, the bright stars of Leo (the Lion).

For millennia, sky-watchers have imagined the stars in the night sky linking into patterns – forming humans and animals and inanimate objects. We call these groupings constellations, after the Latin for “stars grouping together”. Each culture has assigned their own spin on the heavens, usually naming the patterns after things in their everyday experience. For example, south sea islanders saw outrigger canoes. The Inuit in the north saw the Big Dipper as the Caribou and Cassiopeia’s “W-shape” as the Blubber Container, with a Lamp Stand shining nearby.

In modern-day astronomy, the entire sky is divided into 88 officially recognized constellations. The manner in which the stars are connected into stick figures is not regulated, but the boundaries that enclose each constellation are. That way, there are no gaps in the coverage, and every object in the heavens can be placed within one of the 88 regions. By the way, astronomy has a long tradition in China where they connected smaller groups of stars, yielding several hundred Chinese asterisms or 星官, xīngguān.

A handful of the constellations are so distinctive that many independent cultures assigned the same meaning to those stars. A perfect example of that is the spring constellation of Leo (the Lion). The lion was identified as early as 1,000 BCE by the Babylonians, and later by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. To the Greeks it represented the Nemean Lion slain by Hercules during his labours. Only that beast’s own claws were sharp enough to slice its hide.

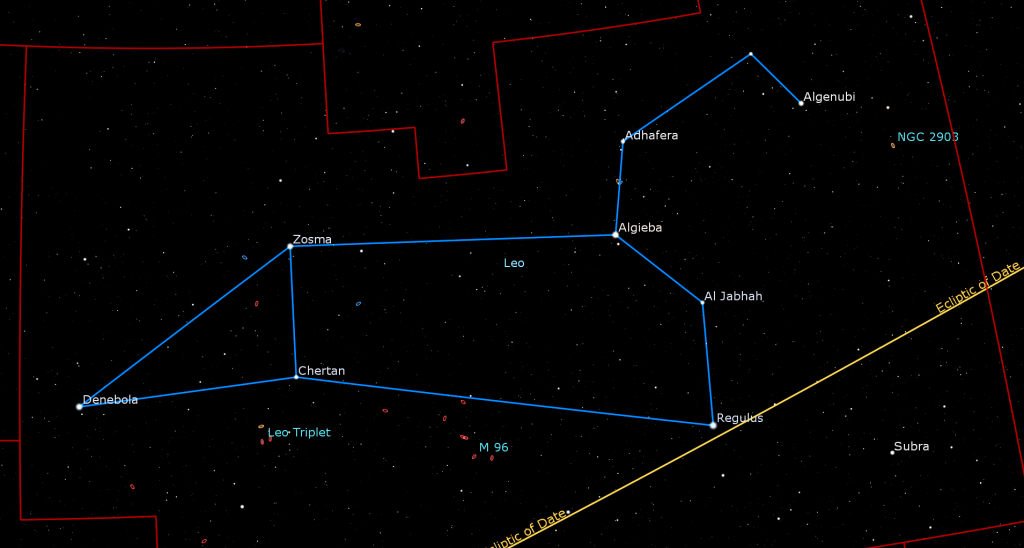

It’s easy to find and recognize Leo, even from suburban skies. Head out on the next clear evening and face east. Leo is a large constellation situated about halfway up the evening sky. (If you are outside around midnight, he’s very high up when you face south.) The imaginary ecliptic line that the Sun, Moon, and planets all travel close to crosses through the lion’s territory, though all of his bright stars are north of it. For this reason, Leo is one of the twelve zodiac constellations. He is positioned with his head facing to the upper right (or celestial west) and his tail pointing down towards the left (east). In some depictions, he has no legs or feet, as if they are tucked underneath him. Tilted tail-downwards in early evening, the lion will level out in the southern sky around midnight, and then descend headfirst in the western sky until almost dawn.

The lion’s brightest star is Regulus (or Alpha Leonis). Regulus means “Little King” in Latin and its Arabic name Qalb Al Asad translates to “the heart of the Lion”. Regulus, the 21st brightest star in the heavens, is blue-white with a small, nearby companion star that can be seen in binoculars or a backyard telescope. Its position almost on the ecliptic allows it be occulted frequently by the moon and the inner planets.

From Regulus, look upwards to the left and trace out another five modestly bright stars arranged in a backwards question mark about 1.4 fist diameters tall with Regulus serving as the “dot”. Some people see a sickle. The shape represents the lion’s neck, head, and mane. The medium-bright, white star that sits a slim palm’s width above Regulus is Al Jabhah (or Eta Leonis). It emits up to 20,000 times more light than our own sun, but its distance of 1,270 light-years makes it dim enough to shine near the limit of visibility for suburban stargazers.

The second star in the sickle from Regulus shines several finger widths to the upper left (or 4° to the celestial northeast) of Al Jabhah. This is a brighter star named Algieba, or “the forehead”. In a backyard telescope, Algieba splits into a very pretty yellow and blue pair of stars, one slightly brighter than the other. An extra, small star named 40 Leonis shines below the close pair. The medium-bright, yellowish star positioned a few finger widths above Algieba is Adhafera (or Zeta Leonis), which comes from the Arabic aḍ-ḍafīrah “the braid/curl”, possibly a reference to its position in the lion’s mane. When viewed in a backyard telescope, that star is bracketed by two bright companion stars named 35 Leo and 39 Leo. (Only the brighter stars in the sky tend to have proper names. The rest have numerical or Greek letter designations.)

The next star in the sickle, found with a larger hop toward Adhafera’s upper right, is Rasalas or Ras Elased Australis (or Mu Leonis), an abbreviation of Al Ras al Asad al Shamaliyy, which means “The Lion’s Head toward the South”. Yellow-tinted Rasalas is only about 125 light-years away from us, and is known to be orbited by a giant planet. At the end of the sickle, a bit lower than Rasala, we find the medium-bright, yellow star Algenubi (or Epsilon Leonis), which marks the beast’s nose. Both Algenubi and Ras Elased Australis mean “the Southern Star of the Lion’s Head”.

A fainter, reddish star named Alterf (or Lambda Leonis) shines just a few finger widths in front (west) of the lion’s nose. That name arises from the Arabic word Aṭ-ṭarf “the View (of the Lion)”. A very similar red star named 31 Leonis shines a short distance below Regulus. And, and even redder star named Pi Leonis shines to finger widths below and to the right of 31 Leonis. Check them out in binoculars!

Let’s trace out the rest of the lion. Starting from Algieba, cast your gaze a generous fist’s width to the left (or 13° to the celestial east) along the lion’s back to find a star of similar brightness named Zosma (or Delta Leonis). It represents the lion’s hip. Zosma is a hot, white star about twice the diameter of our sun – although its rapid spin (100 times faster than our sun’s) has given it an oblate form. We know so much about the star because it is only 54 light-years away.

Angling down and to the left of Zosma by another fist’s width, we reach the star that today marks the lion’s tail. Named Denebola (or Beta Leonis), it is the second brightest star in the constellation. Denebola is a young, blue-white star only a few hundred million years old. It emits quite a bit of infrared radiation, suggesting that this young sun may have a planet-forming dust disk around it. It’s a mere 36 light-years away from us! Remember this star – it’s key to finding some of those galaxies!

The last major star of Leo, named Chertan (or Theta Leonis), sits to the lower right of Zosma and Denebola, forming a nice triangle with those two stars. The name Chertan is derived from the Arabic al-kharātān “Two Small Ribs”, which originally referred to the up-down line formed with Zosma.

Draw an imaginary line from Zosma to Chertan and triple its length. If you aim your binoculars at that seemingly empty patch of sky you’ll discover a rough circle of medium-bright stars about a fist’s width (or 10 degrees) across named Sigma, Tau, Upsilon, Epsilon, Phi, p, and d Leonis. I like to think of them as outlining the mouth of the lion’s den.

With unaided eyes on a dark night, or with binoculars at any other time, search about 1.5 fist diameters to the upper left of Denebola to find a large patch of scattered stars named the Coma Berenices Cluster, Ariadne’s Hair, or Melotte 111. In ancient times, that patch of fuzz represented the tuft at the end of Leo’s tail! Now it is assigned to Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair).

Now that you see the lion’s form – can you see the mouse? It’s easy to imagine the sickle of stars as a mouse’s curly tail, and Denebola and Zosma as the mouse’s nose and eye!

Leo is a favorite of amateur astronomers because it contains a nice selection of relatively nearby and bright galaxies – and Chertan is a nice stepping stone to them!

A medium-bright star named Iota Leonis (labelled Tsze Tseang in some apps) shines to the lower left (or celestial south-southeast) of Chertan. (It’s the same distance from Chertan that Zosma is.) On a moonless night in a location away from city lights, aim your big binoculars or a backyard telescope halfway between Chertan and Iota. There, you should see a triangle of three spiral galaxies known as the Leo Triplet. All three galaxies will share the eyepiece in a quality telescope at low magnification. Two of the galaxies sit closer together. Those are numbers 65 and 66 on Charles Messier’s famous list of deep sky objects, so astronomers call them M65 and M66. A third, fainter galaxy sits a little bit apart. That’s the Hamburger Galaxy or NGC 3628, so-named for its rectangular shape and layers of dark dust resembling a patty and buns.

A second, larger triangle of galaxies is located midway between Chertan and Regulus, and two finger widths below the line joining those two stars. Named the Leo I Group, it contains M95, M96, and M105 – plus another galaxy not catalogued by Charles Messier named NGC 3384. (NGC is the acronym for New General Catalog.)

And that’s just the beginning. A very nice and bright spiral galaxy named NGC 2903 sits just a thumbs width below (or 1.4° to the celestial south of) the star Alterf. Let’s call it the Lion’s Tongue Galaxy. If you spot a fuzzy star with your telescope aimed somewhere in and around Leo, chances are it’s yet another galaxy!

As I hinted at above, the patch of sky located about a fist’s diameter to the rear of Denebola contains dozens of bright galaxies! I’ll talk about them another time…

I presented a deep dive into Leo’s best features for our Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy show in April, 2023. The YouTube link to that is here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, March 30 from 12:30 to 1 pm EST, astronomers from the David Dunlap Observatory will present some online DDO Sunday Sungazing. Registrants will learn how the sun works how it affects our home planet, and see views of the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting. More information and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eye on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!