We Reach Northern Mid-Summer, Perseids Proliferate While the Evening Moon Mounts, and the Teapot Tilts West!

This composite image of Perseid Meteors streaking across the Milky Way was captured by Ali Hosseini Nezhad from Shiraz, Iran in 2023. The three bright stars of the Summer Triangle asterism frame the galaxy. NASA APOD for August 24, 2023

Hello, August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 4th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

We’ve reached mid-summer, astronomically speaking, in the north. The waxing crescent moon will shine above the western horizon for a while after sunset this week, leaving the rest of the night dark for Perseids Meteors and for appreciating the summer Milky Way. Your galactic starting point may well be the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius. Mercury’s departure leaves Venus huddling alone in the west after sunset. Saturn and Neptune appear in late evening, and three more planets will herald sunrise in the east. Read on for your Skylights!

Mid-Summer

The daylight hours are shortening at a faster rate now for mid-northern stargazers. Over the course of this week, we’ll swap almost 18 minutes of daylight for night. That pace will increase until the first day of autumn, and then the daylight will diminish more slowly to the December solstice.

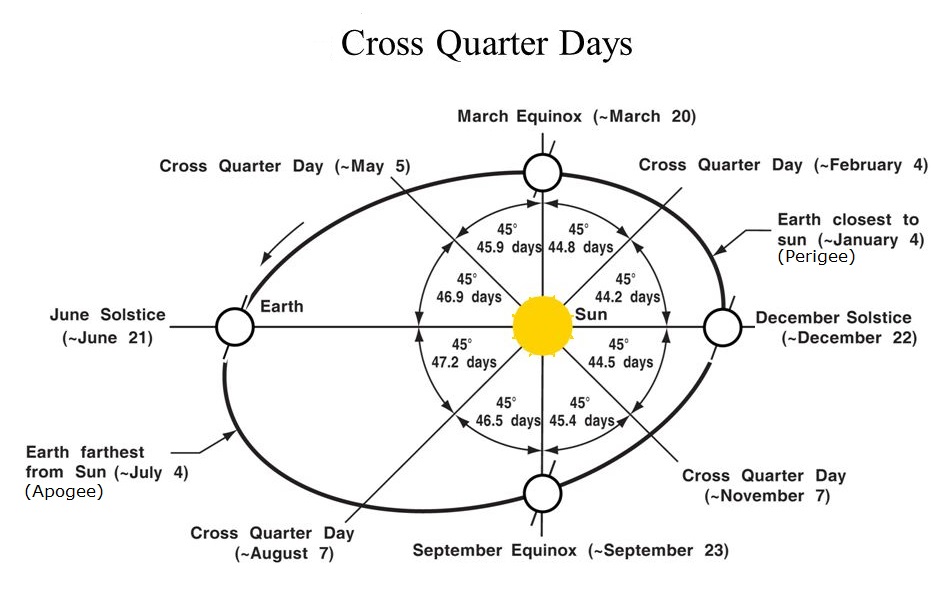

Tuesday, August 6 at 1:45 pm EDT (or 17:45 Greenwich Mean Time) will mark the mid-point of summer in 2024 – falling halfway between the June Solstice and the September Equinox. It is one of the four cross-quarter days, which are the seasonal midpoints following each solstice and equinox. Many pagan groups schedule Lammas or Lughasadh festivals around this time – to celebrate the early harvest. The term “lammas” refers to grain or bread. (J.R.R. Tolkien readers will notice that it resembles the word “lembas”, the Elven Waybread, from the same root.) The next cross-quarter day will occur in three months, during the first week of November. That’s Samhain. But we celebrate it on October 31 – as Halloween!

The Earth reaches it farthest distance from the sun, or aphelion, in early July each year. Since Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion dictate that a planet moves slowest while at aphelion, summer in the Northern Hemisphere is several days longer than winter – so, enjoy those extra sunny days!

Perseids Meteor Shower

The annual Perseids Meteor Shower is the one I look forward to the most. While December’s Geminids and January’s Quadrantids deliver more meteors per hour at their peaks (150 and 120, respectively), cloudy winter skies and bitter cold aren’t conducive to enjoying their displays. The Perseids shower, on the other hand, delivers 60 to 100 meteors per hour at its mid-August peak, which always arrives during the hot, dry part of summer at mid-northern latitudes. Perseids are famous for appearing as bright, sputtering fireballs! Some leave “smoke trails” that dissipate in a few minutes. I’ve already seen a number of terrific bright Perseids, including a fireball early this morning!

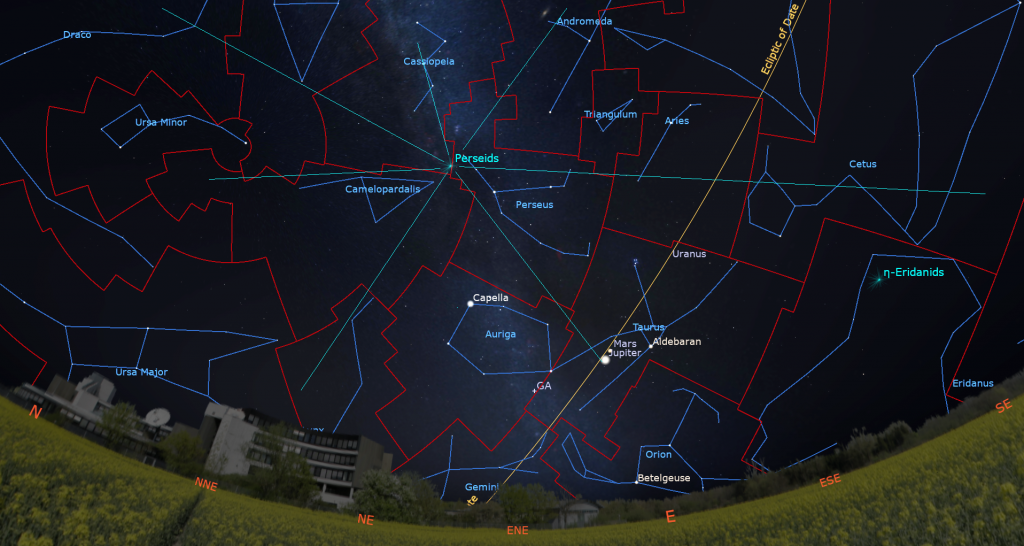

The active period for the Perseids shower is about July 17 through August 24, ramping up towards the peak night and then tapering off. It will peak after midnight in the Americas on Sunday night, August 11. Moonlight obscures the fainter meteors. With a 44%-illuminated, waxing crescent moon setting in late evening, the best time for seeing Perseids meteors in North America will be between 11 pm on Sunday and dawn on Monday morning, while the shower’s radiant in Perseus is high in the northeastern sky. (I explain what that means below.) You can’t see meteors through clouds. If your sky will be cloudy on Sunday-Monday, consider heading out on the clear night falling closest to the peak night.

Here is some more information about why showers happen. My late friend Blake Nancarrow has prepared a very informative chart here that shows how the number of meteors varies throughout a given year. Unfortunately, moonlight obscures meteors by brightening the sky, and Blake’s graph would have to be remade each year to take that into account. Earth’s orbit intersects or passes close to the orbits of quite a few comets. Blake’s graph shows about 20 significant meteor showers – but some of them are produced by the same comet’s orbit intersected twice. He has omitted other, very minor showers.

Meteor showers re-occur on the same dates every year when Earth’s orbital motion around the sun carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. When those comets sweep through the inner solar system, the warmth of the sun causes them to outgas and eject dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) cometary particles along their orbit. Over many orbits (i.e., many years), the material accumulates within an elongated, tube-shaped cloud in interplanetary space. An analogy is the material that falls out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway eventually gets pretty dirty after the truck has driven the same route a number of times – and there’s no wind or rain in space to wash it clean.

When the Earth plows through the debris cloud, some of its particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air along its path – producing the long glowing trails we see.

The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud in space and the angle at which we intersect it, i.e., how long Earth takes to pass through it. The number of meteors will increase nightly as Earth ventures more deeply into the debris field, peak when the particles are most plentiful, and then taper off on the following nights. If the moon is going to be shining in the sky on peak night, you can often arrange to do your meteor-watching a night or two ahead or after the peak, when the moon won’t as bad. I usually work that out for you.

The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion of the debris field, or merely skirt the edges. Due to small variations in orbits any shower’s performance can vary from year to year, independent of the moon. The source of the Perseids material is thought to be a large, 133-year-period comet named 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which was discovered by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862. When it last passed Earth in 1992, it wasn’t visible – but astronomers predict that its 2126 pass could be spectacular! Here’s a link to a 3D model of the comet’s path through the solar system and the Perseids shower. Drag your mouse around to view the geometry.

While visible anywhere in the night sky, meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The radiant for the Perseids sits in northern Perseus (the Hero) – near its brightest star Mirfak and Perseus’ border with Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). Meteor showers are strongest before dawn because that’s the time when the sky over your head is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splattering on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant is overhead, the entire sky down to the horizon is available for meteors. When the radiant is low, many of the meteors are hidden below the horizon. The Perseids’ radiant is low in the northeastern sky during mid-August evenings – and nearly overhead by dawn. You don’t need to know where the radiant is – only that any shower delivers more meteors when its radiant is higher in the sky.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place about 100 km over your head within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of our favourite constellations look the same as ever at the end of a shower! That said, though, each shower’s name comes from the location of its radiant – the stars that Earth is traveling towards on the peak night. (That spot on the celestial sphere shifts each night because we are travelling in an ellipse around the sun.) Some showers are named for defunct constellation (Quadrantids), others use a particular star within a constellation (Delta Aquariids), or a region of a constellation (Southern Taurids).

To see the most meteors, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant, since the meteors near it will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. When you see a meteor, try to trace its path backwards to see if it points to Perseus. You can expect to see solitary sporadic meteors on any dark night. Those ones won’t follow the “radiant rule”!

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use a screen, turn the brightness down, or cover it with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors.

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower will be tapering off until August 23. Those meteors will appear to travel away from that shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), which sits in low in the southeastern sky during evening. Good luck!

The Moon

Even though the moon will return to shine in the evening sky this week worldwide, Milky Way lovers and stargazers located at mid-northern latitudes won’t really have to contend with bright moonlight until next week. That’s because the western ecliptic after sunset has a very tilted angle at this time of year. Moreover, the moon is traveling the part of its orbit that is several degrees below the ecliptic. Those will combine to largely keep the waxing moon from clearing the western rooftops every night even though it will be lingering about 20 minutes longer into evening with each passing day.

This morning, August 4 at 7:13 am EDT, 4:13 am PDT, or 11:13 Greenwich Mean Time, the officially reached its new moon phase while in Cancer (the Crab). Sharp-eyed observers might catch sight of the very slender young crescent moon just above the western horizon near bright Venus tonight (Sunday) after sunset. But I’d wait until Monday.

After the sun has completely set on Monday evening, look just above the western horizon with your unaided eyes (or use binoculars) to spot the slender crescent moon posing less than a lunar diameter above the brilliant planet Venus. They’ll set about an hour after sunset. Skywatchers in different time zones will see the moon and Venus arranged in different ways because the moon slides east by its own diameter every hour. In Europe the moon will sit off to Venus’ right. In the Americas, Venus will be located just below (or celestial south of) the moon. Sharp eyes might also spot Leo’s brightest star Regulus just below them, and Mercury off to their lower left.

For the rest of the week the moon will increase its angle from the sun and wax in phase. It will spend Tuesday in Leo (the Lion) and then enter Virgo (the Maiden) on Wednesday. By then, its pretty crescent will be easily seen over the western treetops every night. Virgo is a very lengthy constellation, occupying 44° of the ecliptic’s 360° circle. The moon will cross her stars until Saturday night, and then join Libra (the Scales) next Sunday.

As darkness falls on Friday evening, the 26%-illuminated, waxing crescent moon will shine to the lower right of Virgo’s brightest star, Spica. In the Americas, the duo will be close enough to share the view in binoculars. Hours later, the moon’s eastern orbital motion will cause it to pass in front of (or occult) Spica. For observers in parts of northeastern Europe, the west half of Russia, and most of Asia, the event will occur in daylight on Saturday, August 10. Folks across northern Indonesia, southern Japan, and western Micronesia will see the occultation in a dark sky. An astronomy app can tell you when the occultation will occur where you live.

The Planets

The brilliant planet Venus is slowly emerging into view in the western sky after sunset. The same ecliptic tilt that will keep the moon low will also be keeping Venus from easy viewing for the next few weeks – but as we approach next month’s September equinox, she will start to climb higher. Venus will be our brilliant “Evening Star”, gleaming high in the western sky throughout fall and winter. If your western horizon is unobstructed and free of cloud or haze, you can start to look for Venus’ very bright dot as the sky darkens this week, especially after about 9 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes. The planet will be less than a palm’s width above the horizon. You’ll need to wait until the sun has fully set to use binoculars. The crescent moon and Venus will kiss after sunset on Monday.

Mercury is dropping sunward, causing it to shift lower in the sky from night to night. Observers living at tropical latitudes can still see Mercury, currently about 50 times fainter than Venus, positioned about a palm’s width to Venus’ left (or celestial southeast) – and lower each day.

Squee!! The creamy-yellow dot of Saturn will catch your eye as it shines in the lower part of the southeastern sky in late evening. The ringed planet will be rising by 10 pm local time this week. That will advance by half an hour with each passing week. Saturn will spend the next 10 months among the rather unassuming stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars named Psi Aquarii sparkling to Saturn’s lower right. The lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two more redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii shine to Saturn’s upper and lower right, respectively. Those five stars range between 143 light-years and 613 light-years away from our sun, but shine at similar brightness due to their various inherent luminosities.

Saturn’s rings, which will effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth next March, already look like a line drawn through the planet’s globe. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, and any size of telescope will show them to you – and Saturn’s moons! Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from Saturn’s upper right (celestial west) tonight to the opposite side of the planet (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many you can see through your telescope if you look closely. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system this year and next year will cause its moons to align in the plane of the rings and produce frequent transits of Saturn’s moons and their black shadows across its disk – but you’ll need a high quality telescope to watch those.

Neptune will rise 20 minutes after Saturn and follow it across the sky every night. The remote, blue planet will be spending this year in western Pisces (the Fishes), a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 11° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn. Neptune will also be located a bit more than a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 2° north) of a medium-bright star named 27 Piscium, allowing them to share the view in binoculars. Other less-brilliant stars nearby named 29 Piscium, 24 Piscium, and 20 Piscium will help guide you to Neptune with a backyard telescope or good, strong binoculars. For now, you’ll need to look at Neptune while it’s higher up and the sky is dark – between about 12:30 and 4:30 am local time.

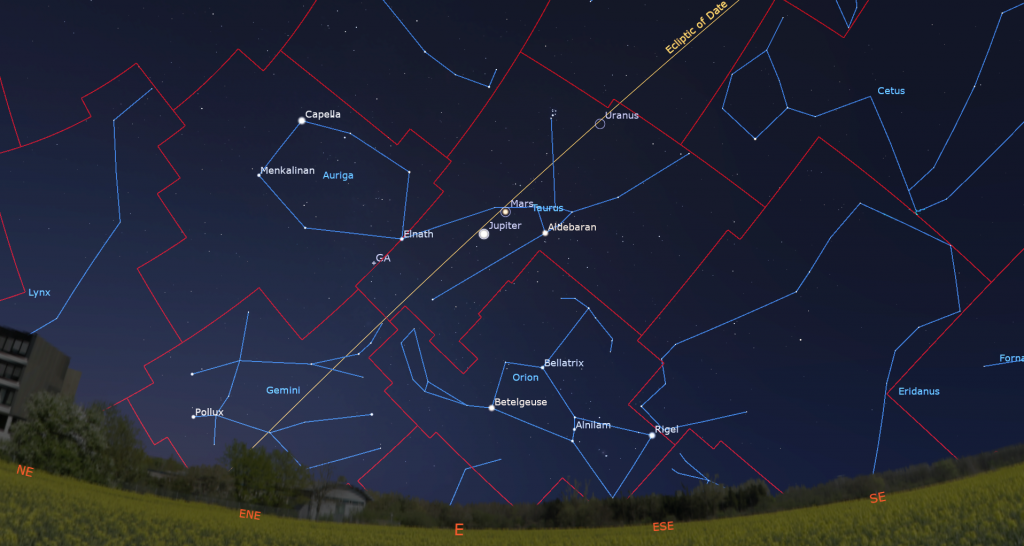

Three more planets will rise within Taurus (the Bull) during the wee hours, and then remain in sight until dawn. Uranus will lead the way after it rises around 12:30 am local time. The magnitude 5.8 planet will be visible in binoculars and a backyard telescope as a dull, non-twinkling, blue-green star. Uranus will stay about a palm’s width to the right of the Pleiades star cluster in the coming weeks.

Next up – the reddish, medium-bright planet Mars will clear the rooftops to the east by about 2 am local time and then remain in sight until almost sunrise, when it will appear partway up the eastern sky. In a telescope, Mars will display a small, rusty-coloured disk. Its position on the far side of the sun from Earth is keeping the planet looking small until later this year. If you do check it out, take notice that Mars is only 89%-illuminated because its angle from the sun is 63°. (When objects are about 90° away from the sun, they show a half-moon shape. Only when they are opposite the sun in the sky are planets fully illuminated.)

Mars’ eastward orbital motion has been almost enough to hold the planet in place while everything else shifts west each day due to Earth’s motion around the sun. As a consequence, Mars has been racing by the other planets. This week it will travel downward (or west-to-east) to the left of the Hyades Cluster, the stars that form the triangular face of the bull. Mars will shine at almost the identical brightness to Taurus’ bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which will be twinkling to the lower right of the red planet. Mars is also heading for a tight conjunction with Jupiter on August 15.

Jupiter, the final planet to rise, will pull your attention once it clears the rooftops around 3 am local time. The giant planet is now well and truly dominating the eastern sky until sunrise. Mars, to Jupiter’s upper right, will decrease its distance from 4.6° to only 1.7° (or several finger widths to a thumb’s width) – allowing them to share the same binoculars field of view.

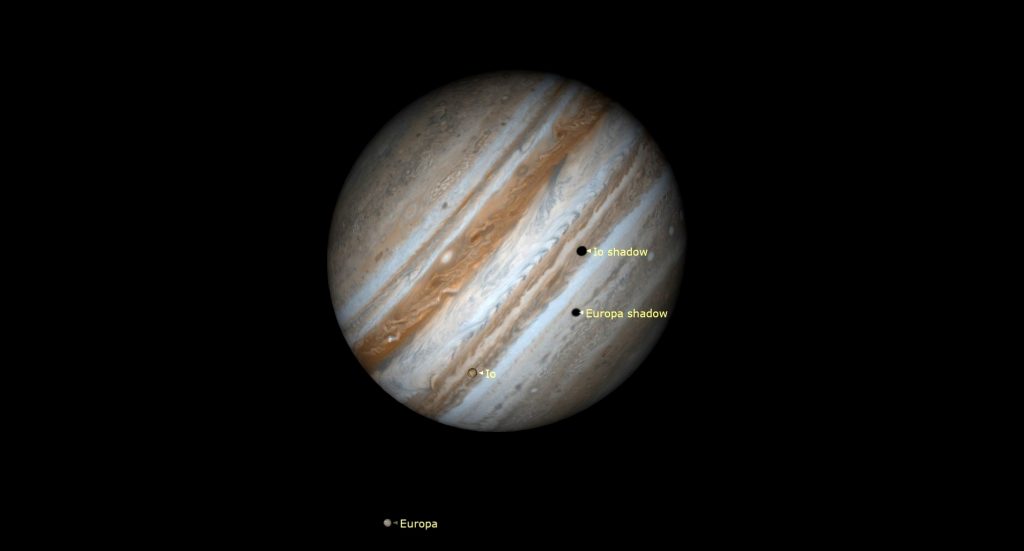

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Tuesday and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. On Wednesday morning, August 7, for observers in most of the Americas, two shadows will cross the southern hemisphere of Jupiter simultaneously. At 2:55 am EDT (or 06:55 GMT), Europa’s shadow will join the slightly larger shadow of Io that began its own crossing several minutes earlier. As the shadows are crossing the planet, Io and Europa themselves will approach and then move onto the planet. Io’s shadow will complete its passage towards 4 am EDT (08:00 GMT), leaving Europa’s shadow to journey on alone until 5:20 am (or 09:20 GMT).

The Teapot Tilts West

This week’s dark skies will be ideal for viewing one of the best asterisms in the sky. An asterism is an informal pattern or picture made up of stars from one or more of the 88 official constellations. The Big Dipper, which is only a part of the much larger constellation of Ursa Major (the Big Bear) is the most famous example. The Summer Triangle asterism, made up of the brightest stars in Cygnus (the Swan), Lyra (the Harp), and Aquila (the Eagle), is another.

The stars of Sagittarius (the Archer), form an obvious Teapot shape with a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the left (or celestial east) and Kaus Australis on the right (west), a pointed spout on the right (west) marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form a handle on the left-hand (eastern) side. The name Kaus used for the bent, up-down line of three stars – Borealis (north), Meridianalis (center), and Australis (south) – refer to the mythical archer’s bow. The center of our galaxy is located only a palm’s width to the right of Alnasl. When the Teapot asterism reaches its maximum height above the southern horizon, around 10:30 pm local time in early August, it will be tilted west – the Milky Way evoking steam rising from its spout. The dwarf planet Ceres will be travelling through the teapot this summer. I’ll post a star chart for it here. It’s a terrific starting point for sweeping up along the Milky Way with your binoculars from a rural site.

Smoky Skies

If you missed my note last week about the impact on stargazing of the smoke from the wildfires that are raging across North America, I posted it here.

An Eye on the Eagle

I posted a tour of the ancient constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) here. This week’s dark skies will let you use the tour.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon, Tue or Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

On Wednesday evening, August 7 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month, observing, and Canadian contributions at Kitt Peak Observatory. Details are here.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, August 9, starting at 7 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

On Friday, August 9 from 10 pm to midnight, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is at ActiveRH.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!