We Stop Saving Daylight, See Some Shooting Stars, and Eye the Moon in Evening While Jupiter Sports Spots!

The trio of craters Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina flank the western edge of Mare-Nectaris. They are easy to see when the lunar terminator lands just to their west as shown here for Wednesday, November 6 (NASA)

Hello, Mid-Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 3rd, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event in Simcoe, Grey, and Bruce Counties, or deliver a virtual session anywhere, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

I describe how the moon controls the timing of Diwali and highlight our natural satellite’s return to the evening sky worldwide. Meanwhile we look at daylight saving time, some weak meteor showers, Pegasus as a celestial signpost, and the evening planet parade, including two Jupiter moon shadow transits accompanied by the great red spot. Read on for your Skylights!

A Belated Happy Diwali!

Like many traditional observances around the world, the timing of the South Asian festival of Diwali, or the Festival of Lights, has an astronomical connection. It lasts five days, always beginning a few days before the new moon phase that falls between mid-October and mid-November – dubbed “the darkest night of the year”. In 2024, Diwali commenced on Monday, October 28 and peaked on Thursday evening, October 31, just hours before Friday morning’s new moon. Did you hear some fireworks, or to see some colourful lights from celebrants, while you were Trick or Treating?

Diwali celebrates the triumph of good over evil after the fall harvest. The festival’s name arises from the Sanskrit expression deepa avali, or “rows of lighted clay lamps” – which were set outside when there was no moon to light the way at night.

The Hindu lunisolar calendar employs twelve 30-day months within a 360-day year. To avoid calendar drift caused by its annual five day shortfall, it adds an extra (intercalary) month every two or three years, in a pattern that repeats every 19 years. Months commence at the full moon, and are followed by a “bright” fortnight. Each mid-month’s new moon kicks off a “dark” fortnight. The Hindu new year begins around the March equinox. The Hindu month that commences around mid-October on the Gregorian calendar is named Kartik or Kartika.

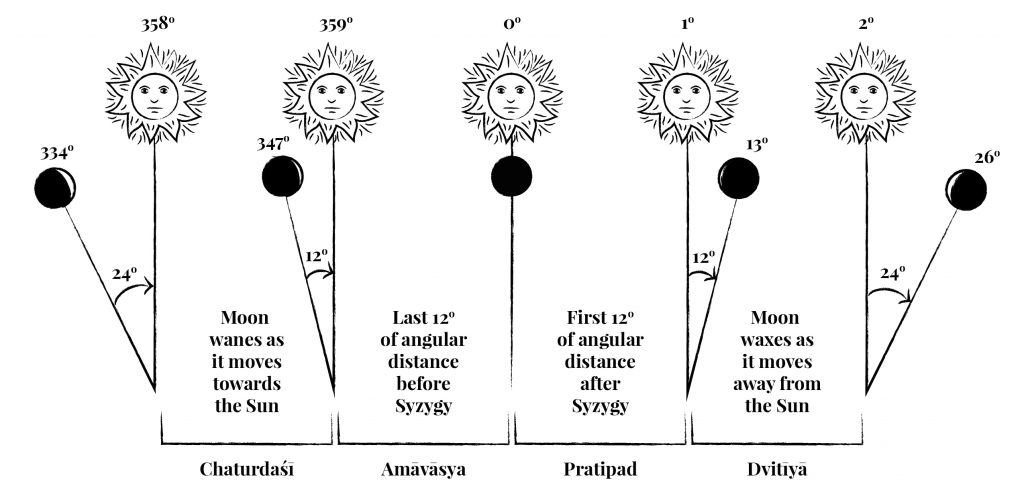

During its orbit around Earth, the moon varies its angle from the sun by about 12 degrees per day, resulting in 30 unique phases, half of them waxing and the other half waning. Each day of the Hindu lunar month is called a tithi, with each tithi bearing a name associated with a particular illuminated phase. On the day before new moon (or syzygy), the moon is less than 12 degrees west of the sun, and appears as a slim waning crescent. That tithi is called Amāvásyā (Sanskrit: अमावस्या), which literally translates to “no moon there”, since it’s rarely observable. The tithi for the day following new moon (slim waxing crescent) is Pratipada. Diwali always peaks on Amāvásyā, the 15th day of Kartika.

Falling Back

Did you remember to set your clocks back by an hour? For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should have been set back by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday morning, November 3 – or before you went to sleep on Saturday night. In North America the “Fall Back” will remain in effect until Daylight Saving Time reverts to Standard Time when we “Spring Forward” on Sunday, March 9, 2025. The changes occur on the second Sunday morning in March and the first Sunday in November. In the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are swapped, the clocks advance in September or October and revert in March or April.

With the end of Daylight Saving Time we’re back to our regularly scheduled program of sunrises and sunsets. Your time zone abbreviation has changed, too. For example, 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is now 7 pm Eastern Standard Time (EST). For those who deal with the timing of astronomical events, the difference between your local time and the international standard Greenwich Mean Time (or GMT), and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC or UT) that astronomers use, is increased by one hour when Daylight Saving Time ends.

For those of us in Toronto, the sun is now rising at about 7 am EST and setting at 5 pm EST. The amount of daylight is decreasing by a whopping 2.5 minutes every day – or 18 minutes every week! The end of astronomical twilight, when the sun is far enough below the horizon for the sky to reach maximum darkness, occurs at about 6:42 pm. As a stargazer, I do appreciate being able to see the stars earlier – but I’m not a fan of the colder temperatures and the cloudier skies of November.

By the way, if you plan to use your telescope on chilly nights, place it in a secure spot outside, with the lens cap on, at least an hour before you head out. That will give the air inside it a chance to equalize with the outside temperature – yielding sharper views. Before you bring the telescope back in, put the lens caps back on to keep the optics from frosting up and/or zip the entire telescope into its case if you have one (or snug a garbage bag around it) while it warms to room temperature.

For most of human history, people woke with the sun and went to bed at dusk. At equatorial latitudes, where most people lived, hunted, and farmed, the number of hours of daylight through the year didn’t vary too much – so that approach worked well. But, as communities spread around the globe and began to use standardize working hours – especially at latitudes farther from the equator where the days lengthened and shortened dramatically throughout the year – people were forced to use artificial light indoors when the sun wasn’t shining into windows.

Scientist/naturalist Benjamin Franklin, in a satire he published while living in Paris in 1784, proposed that Parisians get out of bed earlier to take advantage of the early sunrises in summer – and thereby save money on candles and oil in evening. For the same reason, during the 19th Century it became common for schools and businesses to adjust their operating hours with the seasons – but that practice wasn’t standardized.

A New Zealand entomologist named George Hudson first proposed what became Daylight Saving Time in 1895 – but he wanted the clocks to shift by 2 hours! The idea then spread to England where prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett, who was also an avid golfer, noted that more work (and golf) could be fit into the day if the clocks were advanced during the warm months. While the British parliament toyed with the proposal for years, it was Canada that led the way on Daylight Saving Time!

The first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908, was Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – followed soon after by Orillia, Ontario. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary adopted DST on April 30, 1916 as a way to conserve coal during World War I. Britain and most of its allies, plus many European neutrals soon followed. The USA adopted DST in 1918. Except for Canada, the UK, France, Ireland, and the United States, DST was abandoned after the war; but it was re-instated during World War II and then widely adopted as a result of the energy crisis of the 1970’s.

The Yukon, most of Saskatchewan, and parts of British Columbia don’t change their clocks, nor do India, China, Russia and swaths of Africa and Australia. The inconvenience of twice-yearly clock changes has led to calls to abandon the practice. Some jurisdictions, including Ontario, Canada and the United States, are proposing to remain on DST year-round. I’d prefer to remain on Standard Time and adjust the school schedule. Staying on DST will also mean that existing sundials will be permanently wrong because solar noon will occur at 1 pm, and not at 12 pm.

Meteor Watching

With meteor shower season underway, keep an eye on the sky for a few shootings stars on any clear night this week.

The Southern Taurids meteor shower, which is active worldwide from September 28 to December 8 annually, will reach its maximum rate of about 5 meteors per hour on Monday night, November 4. Some meteors will appear once the sky darkens on Monday evening, but the best viewing time in the Americas will be around midnight when the shower’s radiant in western Taurus (the Bull) will be highest in the sky. The long-lasting, weak shower is the first of two consecutive showers derived from debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the comet’s debris often produce colorful fireballs. This year, an early-setting moon will not affect the shower, though the bright planet Jupiter will shine near the radiant all night long.

The long-lasting Northern Taurids meteor shower, the second shower derived from Comet 2P/Encke, is active worldwide from October 20 to December 10 annually. It will reach its maximum overnight on Monday, November 11 in the Americas. The best viewing time for North American skywatchers will be the hours around midnight when the shower’s radiant near the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus will be well above the horizon, especially after the bright moon sets around 2:30 am local time on Tuesday morning. The Northern Taurids shower typically delivers 5 meteors per hour at its peak. The larger-than-average grain sizes of the particles often produce colorful fireballs.

The recent Orionids shower will end around Thursday and the prolific Leonids meteor shower will start its ramp-up around the same time.

The Moon

The moon will return to shine in the evening sky worldwide this week, but earlier sunsets also mean earlier moonsets, so we’ll have lots of stargazing hours this week.

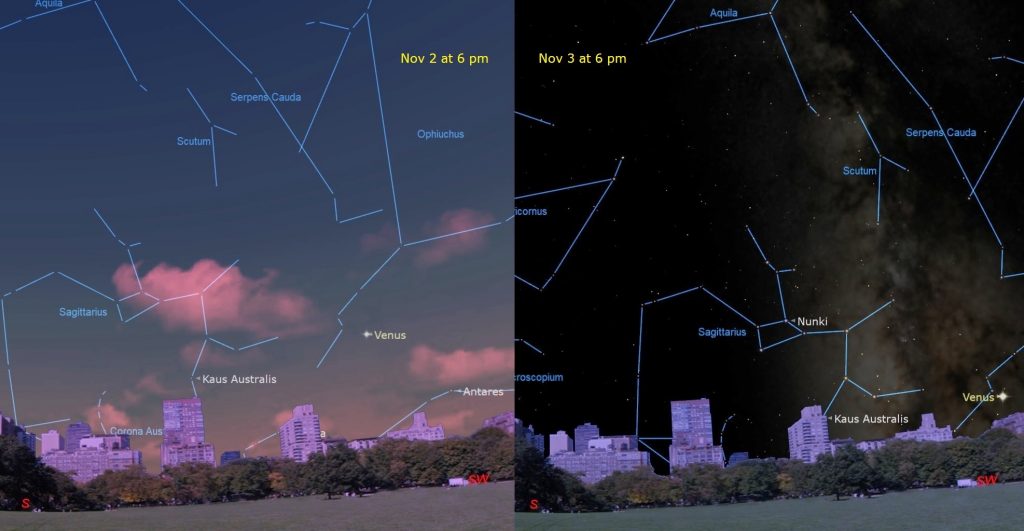

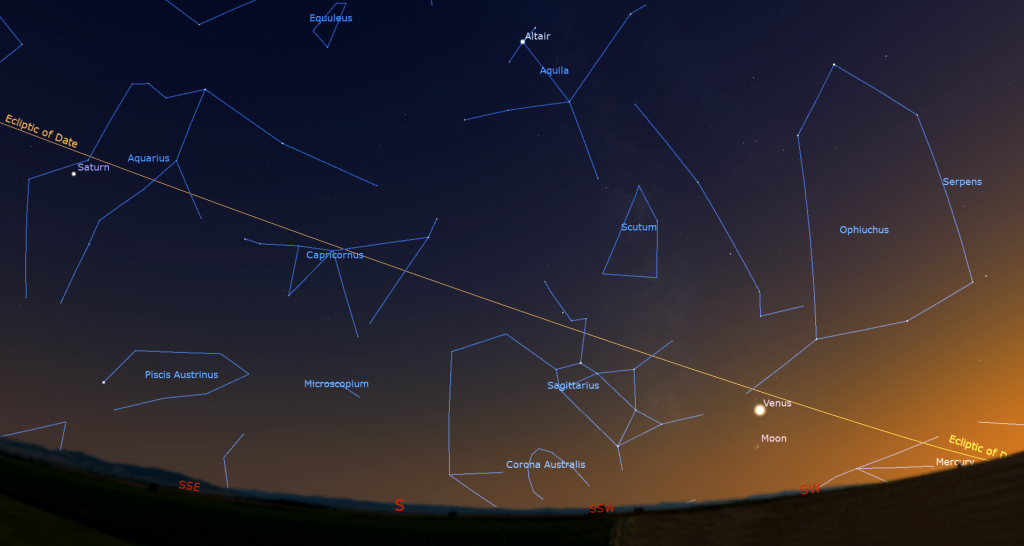

Search just above the southwestern horizon for a short period after sunset tonight (Sunday) to see the slim crescent of the young moon positioned a generous palm’s width to the left (or 7 degrees to the celestial southeast) of the small dot of Mercury and much brighter Venus gleaming more than a fist’s width off to their upper left. Observers living closer to the tropics, where the ecliptic will be more vertical, will see the moon and the two planets more easily. As the sky darkens more, the fainter, but prominent star Antares, which marks the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion), will appear just to the upper left of the moon.

After 24 hours of orbital motion, the pretty crescent moon will hop east to shine several finger widths below (or celestial south of) Venus on Monday. Look for the pair in the lower part of the southwestern sky starting after sunset. They will be close enough to share the view in binoculars and will make a lovely widefield photograph before they set around 6:30 pm local time. Take note of Earthshine, also known as the Ashen Glow and “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The phenomenon appears for several days after each new moon.

The evenings from Tuesday onward will be the best ones for viewing the moon under any amount of magnification. As the moon increases its angle from the sun in Earth’s sky, the half of the moon that is lit directly by the sun will rotate more and more onto the hemisphere of the moon that faces Earth – also known as the near side. The curved boundary that divides the lit and dark portions of the moon is the terminator, along which the sun is just rising on the moon. The lunar terrain beside the terminator is casting long shadows to the west of every elevated feature, while low-lying areas remain inky black. Since that border is slowly creeping west, you can watch how the illumination evolves over hours – but checking back nightly works, too. (Remember to allow your telescope to get as cold as the outside air for best views.)

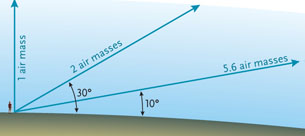

The light from objects you see at the zenith has passed through about 100 km of Earth’s atmosphere to reach you. The closer an object gets to the horizon, the more air we are seeing it through. At 30° above the horizon, we are contending with double the amount of air. Objects on the horizon are shining through about 38 times the zenith amount. More air means more turbulence to blur the view and more intervening moisture and dust that reduce an object’s brightness. Astronomers use the term “air masses” to express the affect.

Our views of the evening moon have been spoiled a bit because the moon hasn’t been climbing very high in the sky. You might have noticed that it seems to be “swimming” when viewed though your binoculars or telescope – as if it’s under water. This has been the case because the moon’s orbit around Earth is tilted by 5.14° from Earth’s orbit around the sun. That allows the moon to drift up and down within a zone about 10° wide as it circles the Earth – like the horses on a carousel. Lately the moon has been hanging out close to its lowest sky position during evening. That has affected its clarity, frequently hidden the moon behind trees or a building, and tinted the moon more brownish during the summer forest fire period.

The moon will set late enough for the stars to appear from Tuesday onwards. On Wednesday, our natural satellite will shine to the left of the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). Venus will gleam to the other side of the teapot.

Also on Wednesday evening, the terminator will fall just to the left of a trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of gray Mare Nectaris. You can tell what order the craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower left (or lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

The waxing crescent moon will swim through the faintish stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) on Thursday and Friday. By then it will be setting in late evening. From Friday to next Monday, The terminator will pass north-south through the large and circular Imbrium Basin, alternatively known as Mare Imbrium or the Sea of Rains. On Friday and Saturday, use any size of telescope to look for sinuous wrinkle ridges slithering over the seemingly flat floor of that large mare.

On the coming weekend, the three spectacular and tall mountain ranges that ring the eastern half of the basin will look spectacular. The dark, round, and smooth crater named Plato will break up the northern arc of the Alpine Mountains. A curving chain of little mountain peaks will poke out of Imbrium’s gray floor below Plato. Those include Montes Recti, Montes Teneriffe, and the single peaks of Mons Pico and Mons Piton. At the southern edge of the big circle, the Apennine Mountain range sinks almost out of sight after it passes the medium-sized, peaked crater Eratosthenes.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its 29.53-day trip around Earth on Saturday morning, November 9 at 12:55 am EST or 05:55 Greenwich Mean Time, which converts to 9:55 pm PST on Friday evening. (Lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation.) First quarter moons always rise around mid-day and set around midnight, so they are also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. At first quarter, the moon’s 90 degree angle from the sun causes us to see it half-illuminated on its eastern side – the terminator becoming straight for one night. On Saturday night the now barely gibbous, medium-bright moon will shine to the right (or celestial west) of the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

Next Sunday night, the moon will visit Saturn in central Aquarius. I’ll share more on that next week.

The Planets

Mercury will continue to lurk just above the southwestern horizon after sunset this week. Its position 1.5 degrees below (or south of) the severely slanted evening ecliptic is keeping the planet too low in the sky for easy viewing from northerly latitudes, but if you live close to the tropics or in the Southern Hemisphere, Mercury is putting on a fine and easy showing for you, exhibiting a waning gibbous shape that grows larger every day as it draws closer to Earth. On Sunday, the waxing crescent moon will shine near Mercury. From now until Mercury once again becomes hidden by the sun’s glare at the end of November, all of the planets will be in the evening sky.

The magnitude -4.0 planet Venus will catch your eye in the lower part of the southwestern sky starting after sunset, though you might need to find a spot to stand where trees or buildings don’t block your view of it. Venus’ position twice as far to the east of the sun than Mercury is lets us see the brilliant planet shining higher above the horizon and setting two hours after sunset. (If you see something bright that is moving left or right, or blinking, it’s an airplane.) The stars will start to appear as Venus is getting ready to set. The pretty waxing crescent moon will pose just below Venus on Monday evening.

While Venus increases its angle from the sun every evening, it is slowly waning in illuminated phase and growing larger in telescopes. Although the distant stars set 4 minutes earlier every night due to Earth’s motion around the sun, Venus continues to set at about 7 pm local time every night because its eastward orbital motion is counteracting the sky’s westward shift. No matter where you live, Venus will be safe to view through binoculars or a telescope after the sun has completely disappeared. Under magnification the planet will show a blurry (due to the extra air you are looking through) 76%-illuminated, football shape..

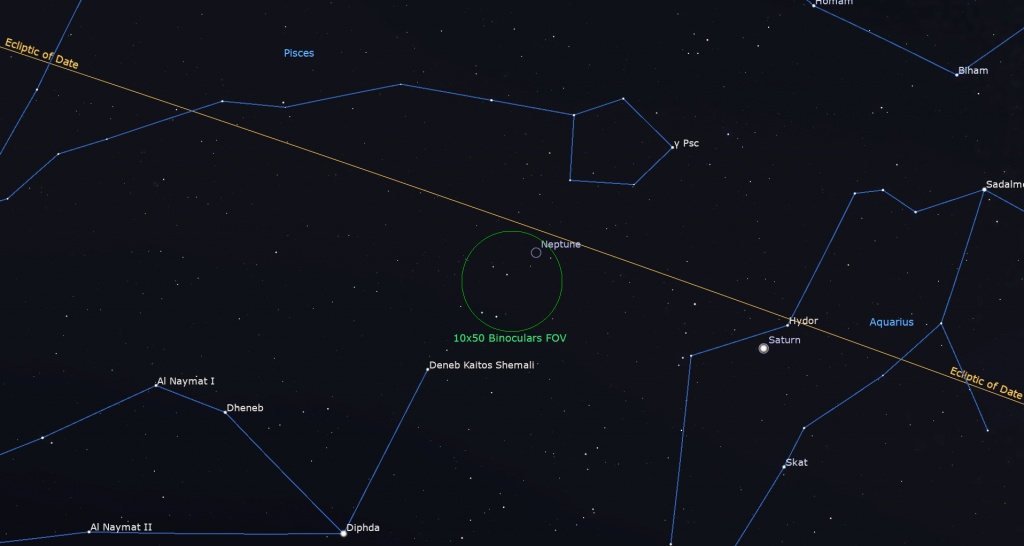

As the sky is darkening, swing around and look southeast for Saturn’s prominent yellowish dot shining in the lower part of the sky with the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) twinkling about two fist diameters below, and a little to the right. Nothing else in that corner of the sky will be as bright (until the moon arrives next Sunday).

The ringed planet will cross the southern sky all evening long within the faintish stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and then set the west around 1:40 am local time. Sharp eyes and binoculars will show you a bent-line trio of stars collectively named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii sparkling a few finger widths to Saturn’s lower left. See if you can tell that the lower two are white, while the higher one is golden. Two redder stars named Phi and Chi Aquarii will appear to Saturn’s left and lower left, respectively. The entire group will fit in your binoculars’ field of view. An even brighter star named Hydor will appear a thumb’s width to Saturn’s upper right (or celestial WNW). Saturn is in the midst of a westward retrograde loop, so its position compared to the surrounding stars can easily be detected by looking at them every few days.

Saturn’s bright, but extremely thin rings effectively disappear when they become edge-on to Earth every 15 years. Since they will do that in late March (while in the pre-dawn sky), the rings already look like a thick line drawn through the planet. Good binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size of telescope will show the rings and some of Saturn’s larger moons, too. In most years, Saturn’s moons are sprinkled around the planet, unlike Jupiter’s Galileans moons, which are always in a line. But while Earth is close to being aligned with Saturn’s ring plane, its moons fall into an imaginary line drawn through the rings.

Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan “TIE-tan” never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus “eye-YA-pet-us” can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea “REE-ya”, Dione “Dee-OWN-ee”, Tethys “Teth-EES”, Enceladus “En-SELL-a-dus”, and Mimas “MY-mass” all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. You may be surprised at how many of those six you can see through your telescope if you look closely when the sky is clear, dark, and calm.

During this week, Titan will start from just to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial ESE) tonight (Sunday), pass below (celestial south of) Saturn on Monday, and then stretch well to Saturn’s upper right (celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks in a line near the rings. Earth’s perspective of the Saturn system will also cause Saturn’s moons and their small black shadows to frequently cross its disk – but you’ll need a very high quality telescope to watch those.

The distant blue planet Neptune (my favorite planet to view in a telescope) is following Saturn across the sky every night. Neptune won’t will set until the wee hours, but view that planet through a large pair of binoculars or a decent backyard telescope while it is highest due south after 9 pm. Slow-moving Neptune will spend all of this year in western Pisces (the Fishes). During early evening it will be in the southeastern sky about 1.5 fist widths to the lower left (or 15° to the celestial ENE) of Saturn and a palm’s width below the circle of stars that forms Pisces’ western fish. Use binoculars to find the upright rectangle formed by the medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium. Neptune will be the bluish, dull “star” sitting about two finger widths above (or 2° celestial north of) that box.

The blue-green planet Uranus, which is closer to Earth, and therefore brighter and easier to see than Neptune, will be climbing the eastern sky during evening. The planet will remain about a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright little Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull) until 2027! Uranus will climb high enough for viewing in binoculars or a backyard telescope after 7:30 pm local time. To get you in the vicinity of Uranus, look for the bright star Menkar shining 2.2 fist diameters off to the right of the Pleiades. Uranus will be a quarter of the way along the line joining the bottom star of the Pleiades to Menkar.

The end of Daylight Saving time has delivered views of Jupiter to even the youngest astronomers! If you face east after about 8:30 pm, the extremely bright, white planet will be climbing the eastern sky. It will reach its highest point due south during the wee hours and then be a beacon in the western sky toward sunrise. From now until early February, Jupiter will be creeping west between the horn stars of Taurus (the Bull), Elnath and Zeta Tauri. They will shine to Jupiter’s upper left and lower left, respectively. Jupiter will also slide ever closer to the bull’s brightest star, reddish Aldebaran. For now it’s a fist’s diameter to the left (or celestial east) of that star.

Any binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto lined up beside the planet. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together, or one moon is eclipsing or occulting another one. All of the moons will gather to one side of the planet on Saturday night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk during early evening on Monday, Wednesday, and next Sunday night, and also around midnight Eastern time on Sunday and Tuesday night. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the black shadows of the Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. In the Americas, the shadow of Europa will cross with Jupiter’s red spot on Sunday night, November 3 between 10:33 pm and 1:00 am EST (or 03:33 to 06:00 GMT on Monday). Io’s small shadow will cross with Jupiter’s red spot on Friday night, November 8 between 8:54 pm and 11:00 pm EST (or 01:54 to 04:00 GMT on Saturday).

We don’t have to stay up too late for Mars now, either! Its reddish dot will rise in the east at about 10 pm local time and chase Jupiter across the sky all night. Castor and Pollux, the “twin” stars of Gemini will shine, with almost the same intensity as Mars, about a fist’s diameter above the red planet. Before sunrise, Mars will shine high in the southwestern sky. In a telescope this week, the red planet will appear as a small, reddish disk. Now that Mars is closer to Earth than the sun is, and approaching us, we will see Mars grow in apparent size and brighten every day until its opposition night on January 15-16.

Pegasus and The Celestial Coordinate System

Fall and winter evening skies feature a group of easy-to-see constellations that are characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – the tale of Princess Andromeda and her rescue by the hero Perseus. The constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse), which also features in their story, becomes well placed for evening astronomy, high in the southern sky, from October to December, and then it gradually sinks into the western twilight by February. It is one of the largest and oldest of the 88 modern constellations – 7th by area. Since it occupies a place in the sky just north of the celestial equator, it is visible from almost everywhere on Earth. Antarctica is the only place where it never rises.

Pegasus contains one of the most obvious asterisms in the sky – a giant square made from four, equally bright stars called the Great Square of Pegasus. Its shape will probably remind you of a baseball diamond when you see it, because it’s usually tilted with one corner downwards. An asterism is a shape or pattern in the sky made up of prominent stars – either stars from a single constellation, or a combination of stars from adjacent constellations. The Big Dipper is an asterism that uses only part of its large constellation Ursa Major.

After it gets dark, face the southeastern sky. The square’s edges are about 16° long (or 1.6 fist widths when held at arm’s length), and about 20° from corner to corner. In early November at 7 pm local time, the square’s centre is a bit more than halfway from the horizon to the zenith. It’s highest in the southern sky at about 8:30 pm local time. It will set in the west before dawn.

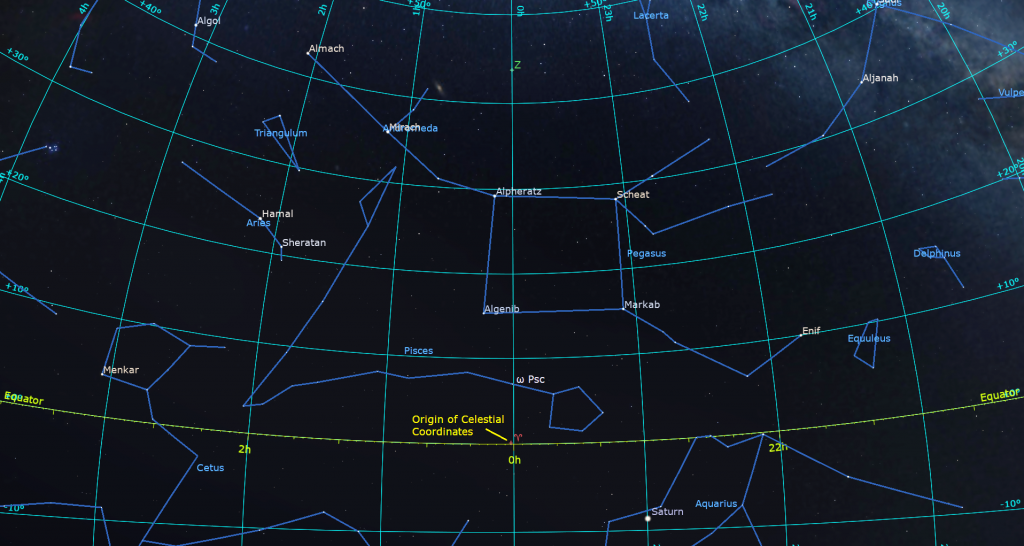

The left-hand, eastern side of the Great Square sits close, and nearly parallel to, the prime meridian of the celestial sphere. On Earth, the Prime Meridian stretches from the North Pole southward through Greenwich, UK, and then continues to the South Pole. Earth longitude coordinates are measured east and west from that line using degrees. For the sky’s globe, the prime meridian begins at the north celestial pole near Polaris, and extends southward through the constellations of Cepheus (the King), Pegasus, Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish), and the lesser-known (for Northerners) constellations of Grus (the Crane) and Tucana (the Toucan) – ending at the south celestial pole in Octans (the Octant). Unfortunately for astronomers aligning their telescopes in the Southern Hemisphere, there is no bright star marking that pole.

To measure east-west in the sky, astronomers use Right Ascension, abbreviated R.A., instead of longitude. In lieu of circumventing the globe from 180 degrees east to 180 degrees west, with each degree subdivided into minutes and seconds, the Right Ascension units are time, employing the length of Earth’s day, from 0 to 24 hours. The sky coordinate for any object along the prime meridian is both 0 hours 0 minutes 0 seconds, or 00h00m00s, and 24h00m00s. Right Ascension values increase moving east in the sky because an easterly object will rise at a later time than a westerly object.

The square’s eastern corner stars Alpheratz and Algenib are positioned at R.A. 00h09m30s and R.A. 00h14m21s, respectively, about two thumbs’ widths east of the prime meridian. Following that edge north toward Polaris, you’ll pass the bright star Caph in Cassiopeia (the Queen) at R.A. 00h10m19s.

Extending the meridian southward, you’ll pass very close to the medium-bright star Omega Piscium and then cross the Celestial Equator (or declination 0°0m0s) a few finger widths below (or 3.5° to the celestial southeast of) the ring of stars that form the western fish in Pisces. That’s the origin point of the celestial coordinate system. The star that is closest to that spot and bright enough to be visible to your unaided eyes and binoculars is XZ Piscium, a magnitude 5.75, reddish M-class star. It’s only a finger’s width from the 0,0 coordinate. In 2024, Neptune is sitting only two finger widths to the lower right of that spot in the sky.

That meridian was selected as prime because the sun passes that point in the sky every year at the Vernal Equinox in March. Over many years, the slow precession, or wobble, of the Earth’s axis of rotation shifts the coordinate system. That’s why star charts are assigned an epoch, such as 2000.0. Apps like Stellarium often report the “of date” or current, celestial coordinates.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, November 6 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting, at the Petrie Science building at York University and also live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks will include The Sky This Month, building and operating an all-sky camera, comets, and more. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!