Wednesday’s Raspberry Supermoon Won’t Belittle the Brightest Lights of July, But it Will Cramp the Comet Near Messier 10!

User Eberhard Stickel requested this north-up image of Comet C/2017 K2 (PANSTARRS) through the luminance filter of the robotic Burke-Gaffney Observatory at St. Mary’s University in Halifax, NS. The dust tail extending upwards reveals the comet’s trajectory downwards. The sun is toward upper right. The double star below the comet is Struve 2122 in central Ophiuchus. The image spans 24 arc-minutes left-to-right.

Hello, mid-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 10th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will become full and super on Wednesday night, flooding night skies worldwide with light. That will somewhat spoil Comet K2’s telescope-close trip past Messier 10. The skies brightest stars will still shine, though, as will the midnight-to-dawn string of bright planets. Read on for your Skylights!

The Super Moon

Earthlings will be treated to the largest and brightest full moon of 2022 this week, flooding night skies worldwide with light. That’ll spoil our views of summer clusters and nebulae – and the comet in Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) – so let’s focus on our natural satellite and run through the science behind it all!

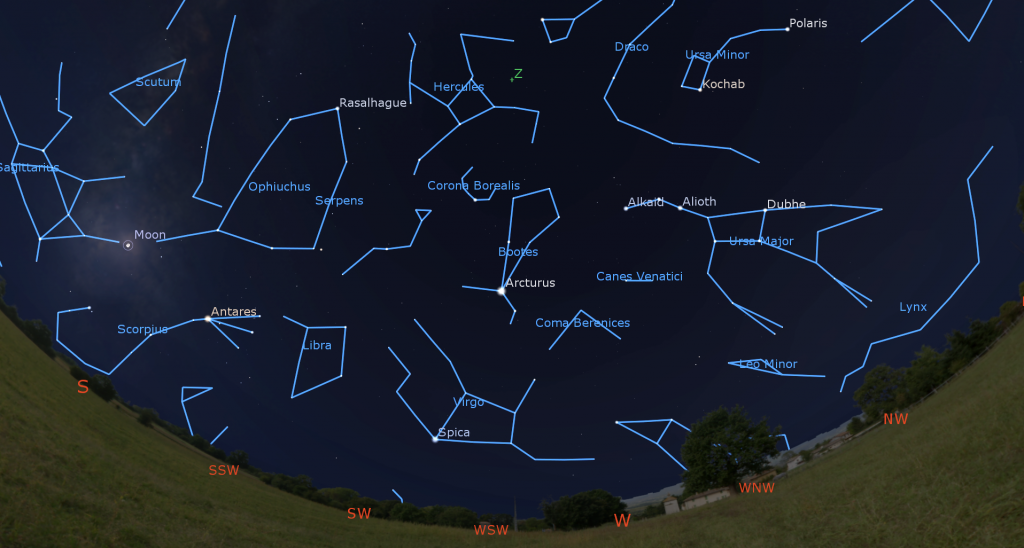

Tonight (Sunday) after dusk, the very bright, 89%-illuminated moon will shine to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of the very bright, reddish star Antares – the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion) – in the lower part of the southern sky. The moon and Antares will be close enough to share the view in binoculars, and in backyard telescopes at low magnification. Summertime moons don’t climb very high in the sky. That’s because the night-time ecliptic is held low while the daytime ecliptic carries the sun extremely high. The moon’s orbit is tipped by 5° compared to the ecliptic, causing it to ride up and down like the horses on a carousel. It happens that the moon is currently ranging a few degrees to the south of the ecliptic, holding it even lower in the night sky.

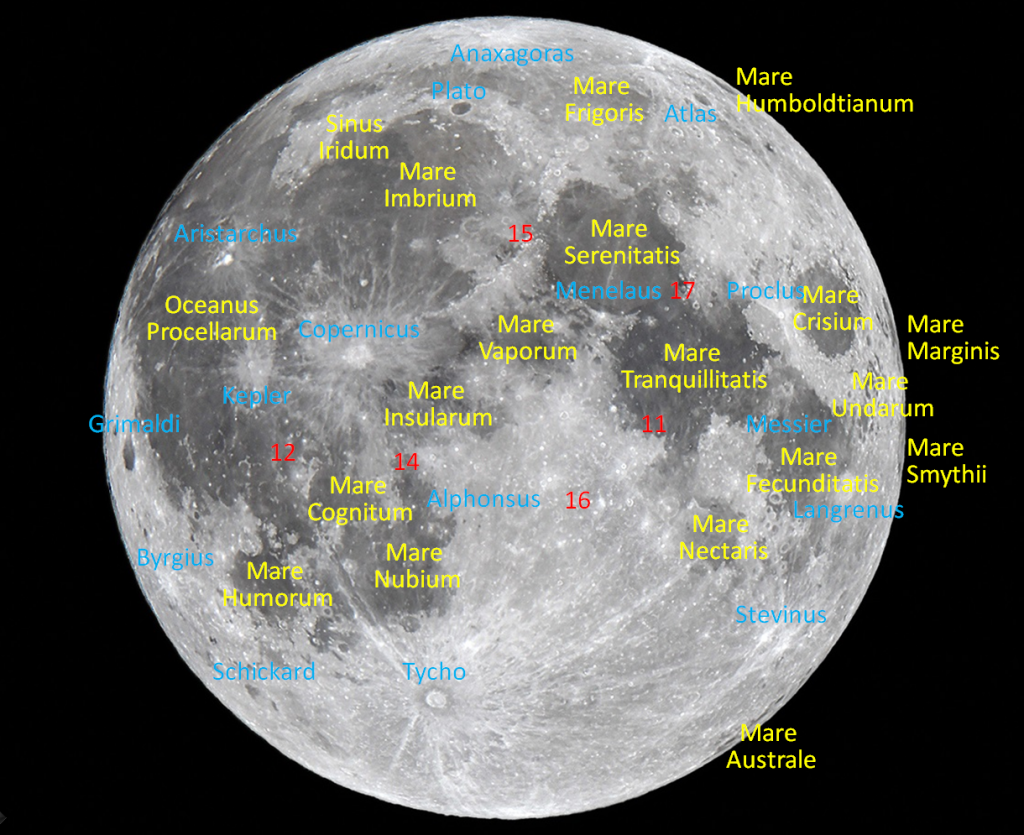

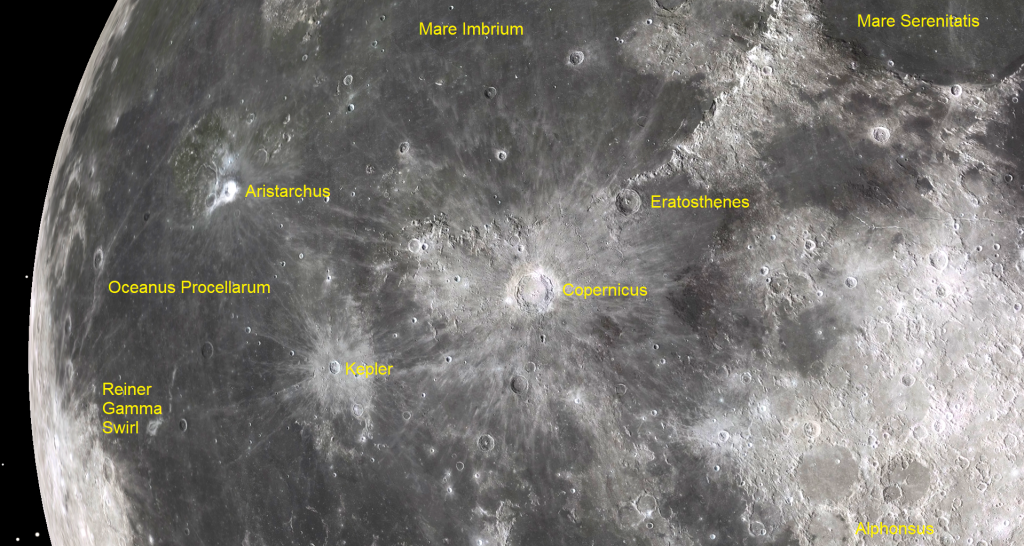

Also on Sunday, the pole-to-pole lunar terminator will arc through the broad, dark expanse of Oceanus Procellarum, which spreads across much of the moon’s western Earth-facing hemisphere. That “Ocean of Storms” covers about 4 million square km, equal to about the western half of Canada. Early in the moon’s history, a large object smashed into the moon at high speed, excavating a shallow bowl, 3,000 km wide, in the moon’s still-cooling crust. Later, dark, iron-enriched magma leaked out of the interior of the moon and flooded that basin with the dark rock we see today.

Early astronomers coined the term maria “seas” for the dark patches on the moon before telescopes revealed that they were actually not wet at all! The very large, round, dark mare in the northwestern part of the moon is Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Showers”. The maria to its south are patchy and interconnected. Mare Insularum “the Sea of Islands” is located directly south of it. Mare Cognitum “the Sea that has become Known” sits to its south. Small Mare Humorum “Sea of Moisture” and larger Mare Nubium “Sea of Clouds” are southernmost, to the left and right, respectively.

The terms “maria” (the dark regions) and “terra” (the heavily cratered bright regions) were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope around 1610. The rest of the moon’s naming system was developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli. In 1651 he published a labeled moon map that modern maps built upon. Riccioli used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has continued that policy.

The maria are all named for weather and states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and for Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical proponents of the heliocentric theory, Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler in the Ocean of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters. I posted his map here.

In the years since the basins were formed, several large craters were punched into them. The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

From Monday to Wednesday the moon’s steady easterly swing around the Earth (it moves by about its own diameter every hour), will carry it through southern Ophiuchus and Sagittarius (the Archer). The moon will reach its full phase on Wednesday, July 13 at 2:38 pm EDT or 11:38 am PDT, which converts to 18:38 Greenwich Mean Time. The July full moon, commonly called the Buck Moon, Thunder Moon, or Hay Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Sagittarius or Capricornus (the Sea-Goat).

Every culture around the world has developed its own stories about the full moon, and has assigned special names to each one. The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Abitaa-niibini Giizis, the Halfway Summer Moon, or Mskomini Giizis, the Raspberry Moon. The Cherokees call it Guyegwoni, the Corn in Tassel Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the June full moon Opaskowipisim, the Feather Moulting Moon (referring to wild water-fowl habits), and the Mohawks call it Ohiarihkó:wa, the Fruits are Ripened Moon.

The moon only appears full when it is opposite the sun in the sky, so full moons always rise in the east as the sun is setting, and set in the west at sunrise. Since sunlight is hitting the moon face-on at that time, no shadows are cast. All of the variations in brightness you see arise from differences in the reflectivity, or albedo, of the lunar surface rocks. The full moon will rise at sunset only for the longitudes near Athens, Greece. By the time it rises in the Eastern Time Zone about 8 hours later, it will already be starting to wane – a sliver of darkness edging its eastern (right-hand) limb.

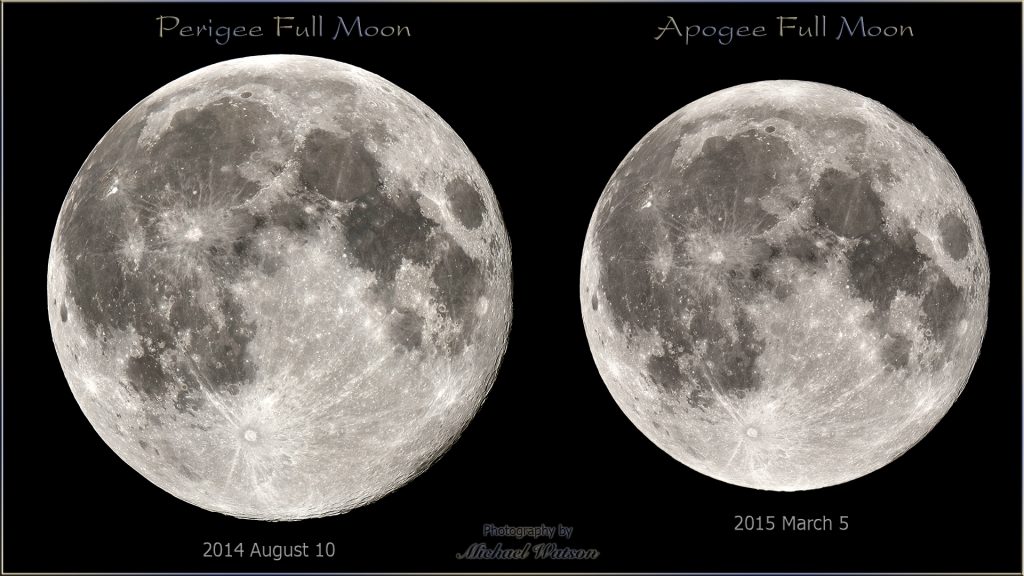

This full moon will occur 10 hours after lunar perigee, the point in the moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth, making this the largest supermoon of 2022. Supermoons occur in consecutive groups or three or four – about every 14 months. During those periods, the moon’s 27.32-day sidereal orbital period that causes perigees and apogees temporarily aligns with the 29.53-day synodic period that produces the moon’s phases. An astrologer named Richard Nolle appears to have coined the term in 1979, and has refined it since then. His “definition” requires that the moon be full while it is also within 90% of its closest approach to Earth – or within about 360,000 km. Supermoons look about 16% brighter and 7% larger than average.

Don’t forget that any moon, even a supermoon, can easily be covered by a pinky fingernail held at arm’s length and one eye closed. That even applies to little children’s tiny fingers! By the way, the astronomical term for an alignment of three celestial objects is a syzygy – in this case, the sun, Earth, and moon. So this full supermoon will be a lunar perigee syzygy.

On Thursday night, the moon will rise among the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) at about 10:30 pm local time, and thin linger into the southwestern morning sky after sunrise. Watch for the bright, yellowish dot of Saturn shining more than a fist’s diameter to the moon’s left (celestial northeast). From Friday to Sunday, the waning gibbous moon will traverse the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). If you stay up late on Sunday, and have a clear view towards the southeast, you can watch the moon rise with Jupiter to its left around midnight.

The Planets

Mercury’s departure has left the lengthy chain of five bright planets – Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, arranged in order of their distance from the sun – still visible for about 90 minutes before sunrise this week.

There’s no need to set the alarm to see a planet, though. The pale yellow dot of Saturn will rise above the east-southeastern horizon soon after 10:30 pm local time. Once it rises high enough, it will shine among the modest stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Toward sunrise, Saturn will be fading from view in the lower part of the southwestern sky. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s globe extending above and below its tilted rings, and up to a handful of its moons arrayed all around the planet. Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift to the right above Capricornus’ easterly tail star Deneb Algedi over the coming weeks. Don’t forget that the bright, waning gibbous moon will lead Saturn across the sky on Thursday night and then shine just a slim palm’s width below (or 5° to the celestial southeast of) the ringed planet on Friday night.

At the end of this week, the very bright, white dot of Jupiter will begin to rise before midnight local time – joining Saturn in the evening sky for the rest of the summer and autumn. Jupiter will climb to halfway up the southeastern sky by sunrise. Good binoculars will show the planet’s little disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons. They make different arrangements each day. Any size of telescope will show dark bands running parallel to Jupiter’s equator. The Great Red Spot will cross Jupiter on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday morning. The small, black shadow of Io will cross Jupiter (with the Great Red Spot!) on Friday morning. Jupiter will spend the next two months gliding through the northwestern corner of Cetus (the Whale).

The medium-bright dot of red-tinted Mars will appear low in the eastern sky after 2 am local time, shining about 2.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Jupiter. Mars’ distance from Jupiter will increase a little bit every morning. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. The red planet will brighten very slowly and grow larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. Extremely bright Venus will clear the east-northeastern treetops by 5 am local time every morning. Venus will exhibit a waxing, nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. The planet is creeping closer to the sun day by day. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before sunrise, please!

This week the main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta will be positioned a generous fist’s diameter to Saturn’s lower left (or 13° to its celestial east). On Tuesday, Vesta’s eastward prograde motion through the background stars of central Aquarius will slow to a stop. After that, Vesta will commence a westward retrograde loop that will last beyond opposition in late August until early October. In mid-July Vesta’s magnitude 6.37 speck will be observable in binoculars and small telescopes, especially between about 1:30 and 4:30 am local time (i.e., while it’s highest in a dark sky). Look for it several finger widths to the upper right (or 3 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the medium bright star Skat (aka Delta Aquarii) or two finger widths to the right of the fainter star Tau Aquarii.

During the same hours of the morning you can use a telescope to seek out the blue speck of magnitude 7.9 Neptune, which will be positioned a finger’s width to the upper right of a small star named 20 Piscium. That star sits a fist’s diameter to the right of Jupiter – on the line joining Jupiter to Saturn.

Uranus will be sitting about midway between the Pleiades star cluster and Mars this week. Its magnitude of 5.8 will allow you see it in binoculars and any size of telescope, especially between 3:30 and 4:30 am local time. The brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis). Uranus is several finger widths to its right (or 4° to the celestial southwest).

Mercury will pass the sun at superior conjunction (i.e., on the far side of the sun from us) on Saturday. Then it will join the western post-sunset sky later this month. .

Brightest Lights of July

While the moon is very bright (and super) the brightest stars can still be seen – so it’s worth learning their names and some fun facts about them. They are also the first stars to appear as the sky darkens – the ones we wish upon! Here’s a tour of the brightest lights on July evenings.

Astronomers use the logarithmic magnitude scale to indicate visual brightness of objects. I’ll mention those numbers below – but you don’t need to remember them. The star Vega anchors the scale at magnitude 0.0. Each integer higher reduces the brightness by 2.5 times, and each integer lower increases the brightness by the same factor, and vice versa. Polaris, the North Star, shines at magnitude 1.95, which is 6.3 times fainter than Vega, i.e., 2.5 times 2.5. A magnitude step of 0.5 changes the brightness by about 50%.

If you face southwest after sunset on a clear evening, and cast your gaze halfway up the sky, you’ll spot yellow-orange Arcturus. It’s hard to miss! At magnitude -0.15, it’s not only the brightest star in Boötes (the Herdsman), but also the fourth brightest star in the entire night sky. A “neighbour” of ours at only 37 light-years distance, Arcturus means “Guardian of the Bear” in Greek, because it rises after Ursa Major (the Big Bear), which sits to its upper right (celestial west). Arcturus has that colour because it is just passing middle-age for a star, starting on its way towards the red supergiant stage.

Speaking of the bear, the Big Dipper, which is composed of the western part of Ursa Major, is dangling downward in the northwestern sky. Its stars all shine at about magnitude 2, but the bowl stars are somewhat fainter than the handle stars. Can you tell? The dipper’s stars point to Polaris, which shines 48th brightest in the northern sky.

Magnitude 0.95 Spica, the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden) and 16th brightest in the entire sky, will be twinkling a few fist diameters below Arcturus, over the southwestern horizon. Its name arises from the Latin expression for “[Virgo’s] ear of [wheat] grain”. That star is a whopping 250 light-years away!

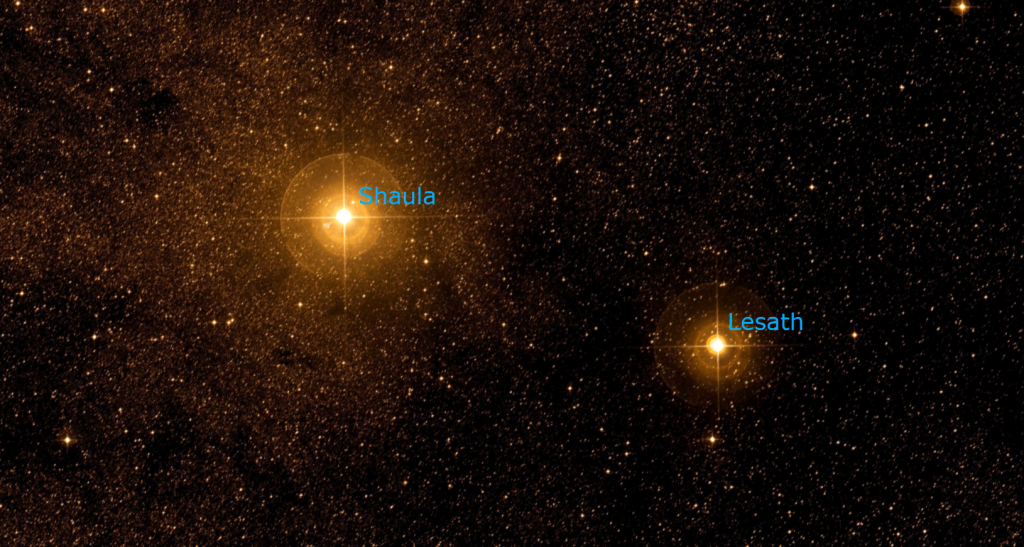

If your southern horizon isn’t blocked by trees or buildings, look for very bright, reddish star Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion). That magnitude 1.05 star, 15th brightest in the night sky, is 554 light-years away. If your view allows for it, look 1.7 fist diameters to Antares’ lower left for the magnitude 1.60 star Shaula, which marks the stinger at the tip of the scorpion’s curled tail. 571 light-years distant Shaula is 23rd in brightness – but it tends to appear fainter that that when seen through the extra-thick layer of Earth’s atmosphere so close to the horizon – a phenomenon that astronomers call extinction. Antares will anchor our Milky Way explorations later this summer. More on that in the coming weeks.

Our magnitude 0.00 star Vega, in Lyra (the Harp) will be climbing the eastern sky during mid-July evenings and crossing the zenith around midnight local time. The fifth brightest star, it matches Arcturus in intensity, but it shines with a blue-white colour indicative of its much higher temperature. Vega is 25 light-years away from us. Two more bright, white stars form the Summer Triangle asterism. To Vega’s lower left (or celestial northeast) you’ll find magnitude 1.25 named Deneb, the tail of Cygnus, the Swan (19th brightest). Altair, 12th brightest, sits about 3.5 outstretched fist diameters to the lower right of Vega (or 34° to the celestial SSE). Deneb is 1400 light-years away, while Altair is a mere 17 light-years distant.

The bright planets Jupiter and Saturn will soon be outshining those stars. Don’t be fooled by them!

Faint Comet Update

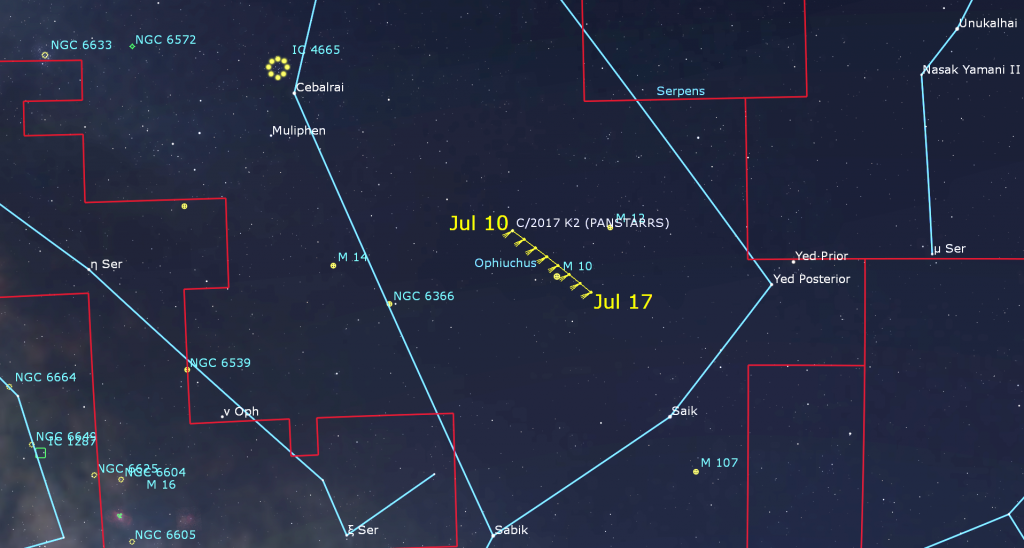

The bright moon will spoil our views of comet C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS) this week. The comet is still near its peak brightness of about magnitude 8.5. It will be travelling downwards to the right (or celestial southwestward) through central Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Ophiuchus’ Dalek-shaped, boxy form sits about halfway up the southern sky in late evening. From Tuesday to Saturday night, the comet will pass telescope-close to the big globular star cluster named Messier 10 (aka NGC 6254) – closest on Thursday.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Monday, July 11 at 7 pm EDT, local science outreach superstars Misha Gajewski and Sara Mazrouei will host The Story Collider: Toronto’s Online Story Hour – Expectations, a night of true, personal stories about science and expectations! You’ll hear four stories, from assumptions about people to experiments, and everything in between. This show will be outdoors at Pamenar, 307 Augusta Avenue, Toronto, ON, M5T 2M2. In the event of rain, the show will be rescheduled to Monday July 18, 2022. Details and Eventbrite links are here.

On Tuesday, July 12 at 7 pm, I’ll be delivering a free, online presentation for Vaughan Public Library about summer stargazing, and some upcoming celestial events to catch. Details and the registration link are here.

RASC’s Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Friday night, July 15 from 9:30 to 11 pm EDT, the DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Sunna Withers, a first year MSc student at York University studying high redshift galaxies with the James Webb Space Telescope. She’ll speak on High Redshift Galaxies and the Early Universe. There will also be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday July 13, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 16 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!