Merry Perihelion, Max Sized Venus and Maximum Mercury, Dual Lunar Phases, Meteors from a Fossil Constellation, and Three Deep Sky Tours!

With unaided eyes, three patches of light make up the sword of Orion, which hangs below his famous 3-starred belt. My friend John Deans of Toronto captured this image of Orion’s Sword while in Bancroft during February, 2021. Even binoculars will reveal that the central patch of light is the splendid Orion Nebula, also known as Messier 42. The grouping of bright stars at bottom centre are “the Lost Jewel of Orion’s Sword”, particularly the magnitude 2.75 star named Nair al Saif, and sometimes called Hatysa, Iota Orionis. Well above the Orion Nebula is the ghostly Running Man Nebula (Sh2-279), one the sky’s brightest reflection nebulas – composed of blue gas, darker dust, and stars in a package spanning 42 by 26 arc-minutes across.

Merry Perihelion, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 2nd, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The Earth veers closest to the sun this week. A string of bright planets in the western post-sunset sky will be joined by the waxing crescent moon, which will reach both new moon and first quarter phase in the same week. The mostly moonless week, will benefit the short Quadrantids meteor shower and the sights in Orion, Taurus, and Auriga. Read on for your Skylights!

Earth Closest to the Sun

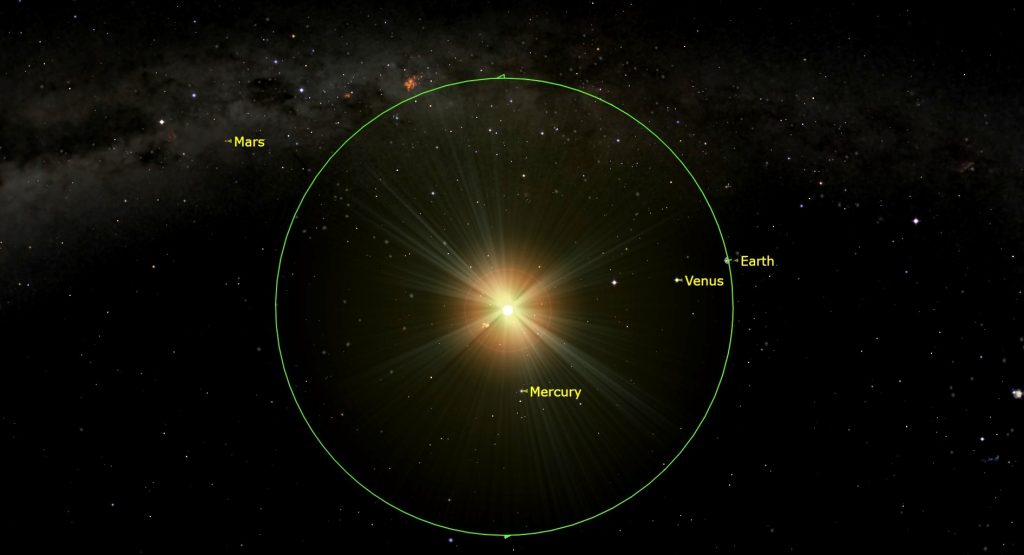

Merry Perihelion! On Tuesday morning, January 4 at 07:00 Greenwich Mean Time, or 2 am EST, the Earth will be at perihelion, its minimum distance from the sun for the year. At that time Earth will sit 147.105 million km from our star – or 1.66% closer than our mean distance of 1.0 Astronomical Units. Earth’s distance from the sun varies throughout the year because our orbit is elliptical enough to varying the Earth-sun distance by 3.3%.

Do you feel warmer? You shouldn’t – as winter-chilled Northern Hemisphere dwellers will attest, daily temperatures on Earth are not controlled by our proximity to the sun, but by the number of hours of daylight we experience, which is only about 9 hours at this time of the year in the Great Lakes region.

See Medusa’s Pulsing Eye

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most accessible variable stars for stargazers. This star has been known to vary in brightness since antiquity – so the ancient Greeks decided that it represented the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head is being held aloft by Perseus (the Hero). Algol’s visual brightness dims noticeably for about 10 hours, on a regular, predictable schedule that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. This happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. This is known as an eclipsing binary system.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the star Almach in Andromeda (the Princess), which is located a bit more than a fist’s diameter above Algol. On Sunday, January 2 at 7:42 pm EST (or 00:42 GMT on January 3), Algol will have faded to its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4. That’s almost exactly the same as Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star that sits two finger widths to Algol’s right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south). When at minimum brightness, observers in the Eastern Time zone will find Algol high in the eastern sky. Five hours later, at 12:42 am EST (or 05:42 GMT), Algol will be halfway up the western sky, and will have brightened to its usual magnitude of 2.1.

Use the very bright stars Aldebaran, Capella, and Mirfak to guide you.

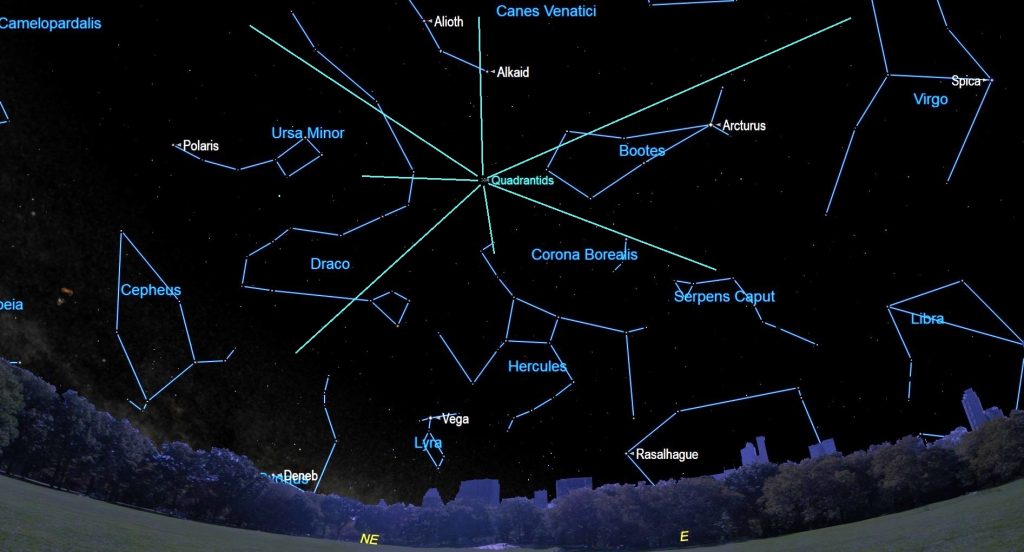

Quadrantids Meteor Shower Peak

Named for a now-defunct, northerly constellation called Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), which used stars in northern Boötes (the Herdsman), the annual Quadrantids meteor shower runs from December 30 to January 12. This shower’s most intense period, when 50 to 100 meteors per hour can occur, lasts for only about 6 hours surrounding the peak, which is predicted to occur on Sunday, January 3 at 21:00 Greenwich Mean Time (or 4 pm Eastern time). During those hours, the Earth will be traversing the densest part of a cloud of tiny particles in space that were deposited over time by the repeated passages of an asteroid designated 2003EH.

When the particles strike our upper atmosphere at tremendous speed, they ionize the air molecules along a 1-metre wide zone that can stretch for kilometres – producing the streaks of light we see overhead as meteors. Quadrantids commonly produce bright fireballs because the stony particles are also burning up.

With the peak on Monday afternoon in the Americas, the optimal times for viewing Quadrantids there will be before dawn on both Monday and Tuesday – although fewer Quadrantids will be seen. Observers in eastern Asia will have the best show – before dawn on Tuesday morning – when the shower’s radiant, which lies beyond the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle, will be high in the northeastern sky during the peak of the shower. Meteor showers are usually worldwide events – but this one’s very northerly radiant will not climb above the horizon for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, reducing the numbers for them. Happily, the peak night will be moonless worldwide.

To see the most meteors, find a wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. The fields of view of binoculars and telescopes are too narrow to be useful for meteors. Don’t spend too much time watching the radiant because the meteors appearing near that location will be short. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. Just keep your eyes heavenward – even while you are chatting with companions. Don’t forget to bundle up, and good luck!

Comet Leonard Update

Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) will pass the sun until at perihelion tomorrow (Monday). At that time it will be nearly as far from the sun as Venus – not close enough to risk destruction by overheating. Recently, the comet has been experiencing more warming, which has resulted in increased gas and dust – brightening it, and lengthening its tail. As it increases both its distance from Earth and the sun after Monday, Comet Leonard will rapidly fade in size and brightness. As of today (Sunday), it has a visual magnitude of about 5.0, which is comparable to the faintest star you can see with unaided eyes from the suburbs.

The comet is only observable from the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere now, where it can be seen through binoculars, telescopes, and in long-exposure photos in a dark sky during evening. This week, the comet will be positioned about two fist diameters to the left (or 19.5° to the celestial SSE) of Saturn, in southwestern Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish), near that constellation’s border with Grus (the Crane) and Microscopium (the Microscope).

The Moon

This week will host two moon phases! At 1:33 pm EST or 18:33 GMT today (Sunday, January 2), the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time it will be located in Sagittarius (the Archer) and will be positioned a few finger widths below (or approximately 4.3 degrees south of) the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of a new moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, our natural satellite becomes completely hidden from view for about a day. This new moon will occur less than a day after lunar perigee, resulting in large tides around the world

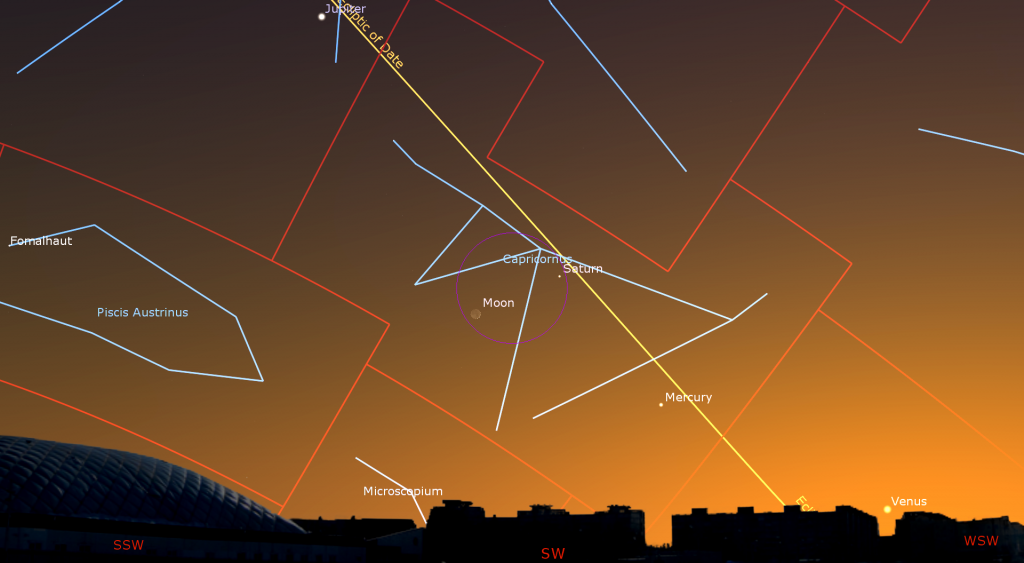

The rest of this week will be terrific for appreciating our natural satellite while it treks across the sky in early evening. If skies are clear on Tuesday, look low in the southwestern sky after sunset for the pretty, slender crescent of the young moon – possibly graced with Earthshine. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth which slightly brightens the un-illuminated parts of the crescent moon. The planets Saturn and Mercury will be several finger widths to the moon’s upper right and a fist’s width to the lower right, respectively – with much brighter Venus way down to the lower right. Jupiter will shine well above the moon.

On Tuesday evening, the moon will shine to Saturn’s left. On Wednesday evening, the waxing crescent moon will climb to sit a palm’s width below (or 6 degrees to the celestial southwest of) bright Jupiter in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn, Mercury, and Venus will still be strung out to their lower right – although Venus will set quickly after sunset. Keep watching for Earthshine! The moon will wax in phase every evening as its angle from the sun increases. That causes the curved, pole-to-pole boundary dividing the dark and lit hemispheres, the terminator, to migrate steadily west across the moon’s disk. The best views of the moon in binoculars and backyard telescopes are in the illuminated strip running along the terminator.

After spending Wednesday to Friday crossing Aquarius, the moon will spend the coming weekend swimming along the crooked border between Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes). The second of two moon phases this week will occur next Sunday evening! At 1:11 pm EST (or 18:11 GMT), the moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth. The relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see it half-illuminated – on its eastern side. The terminator will be a straight line. At first quarter, the moon always rises around noon and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky.

The Planets

During clear evenings for the early part of this week, we’ll still be able to glimpse the very bright planet Venus perched just above the west-southwestern sky for a short time after sunset. (Be sure that the sun has completed dropped out of sight before turning binoculars or telescopes on Venus.) Venus’ angle from the sun is diminishing by about a thumbs width every night, making it increasingly harder to see against the bright sky. In space, Venus is traversing the zone between Earth and the sun, so Venus is closer to us, looks larger and is showing a very thin crescent. This will be our final chance to see Venus in evening until November, 2022!

When Venus reaches inferior solar conjunction on January 8-9, our sister planet will be closer that any planet has been to Earth in a century – a mere 0.266 Astronomical Units, 39.767 million km, or 133 light-minutes. Telescope views of the planet will be very risky while it’s that close to the sun. Experienced observers might glimpse Venus’ razor-thin crescent and its swollen apparent disk diameter of 63 arc-seconds in the daytime!

This week, magnitude -0.71 Mercury will be in the southwestern sky, too – climbing away from the sun until Friday. On Friday morning, January 7 in the Americas, Mercury will reach its widest separation of 19 degrees east of the Sun (or greatest eastern elongation), and maximum visibility for the current apparition. That timing means that Mercury will appear almost as far from the sun on both Thursday and Friday. With Mercury positioned just below the evening ecliptic in the southwestern sky, this appearance of the planet will be a relatively good one for both Northern and Southern Hemisphere observers. The optimal viewing windows at mid-northern latitudes will start around 5:30 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. From the weekend onwards, Mercury will drop sunward with alacrity because it is nearing its own perihelion date, when planets move their fastest.

Once the sky darkens a little more, Saturn will appear about a fist’s diameter above the southwestern horizon. Saturn is in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and Jupiter is next-door in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn will set in the west shortly after 7 pm local time, with Jupiter 90 minutes behind that – so observe each planet as early as you can spot it, while it’s higher. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Both planets are being carried relentlessly sunward due to Earth’s orbital motion. Once Jupiter becomes unobservable beside the sun in a few weeks, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet (Saturn)! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn.

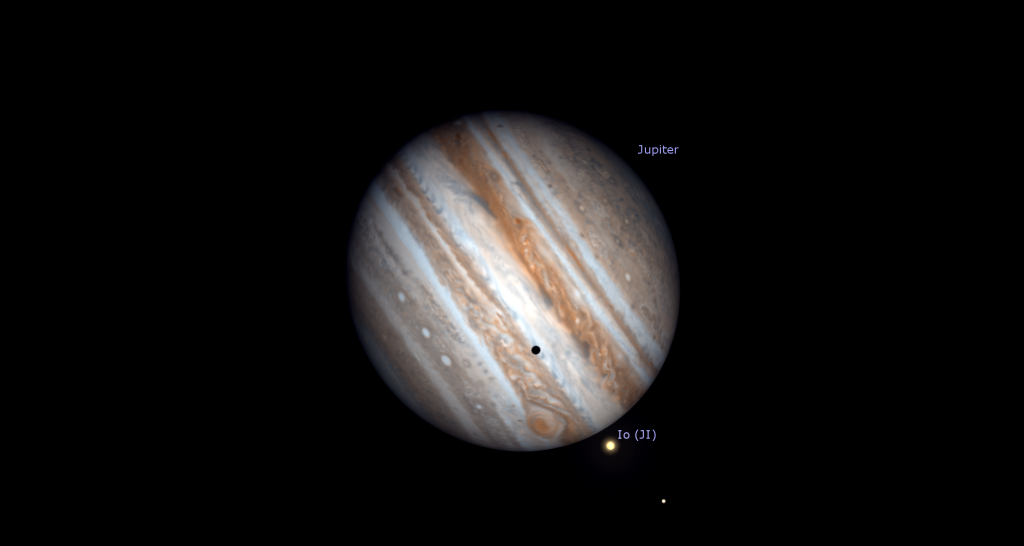

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, and in mid-evening on Wednesday (with Ganymede’s shadow). From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Wednesday evening, January 5, observers in the Americas with telescopes can watch the large round shadow of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede cross the planet with the Great Red Spot between 6:25 pm EST and 9:40 pm EST (or 23:25 and 02:40 GMT). On Thursday, Io’s small shadow will cross between 4:55 pm and 7:05 pm EST, with the GRS for part of that.

Distant, dim Neptune is in the evening sky, too – near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes). The magnitude 7.9 planet is also two fist diameters to the upper left (or 20° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. Neptune continues the string of planets – starting at Mercury and Venus – that traces out the plane of our solar system across the sky. Try to view Neptune in early evening, while it sits higher in the sky. It’ll set around 10:30 pm local time.

Over in the southeastern sky, Uranus is shining at magnitude 5.7. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. Uranus is also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially around 7:45 pm local time, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southern sky. Two fist diameters farther east, towards the bright, reddish star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull), you’ll find the dwarf planet named (1) Ceres.

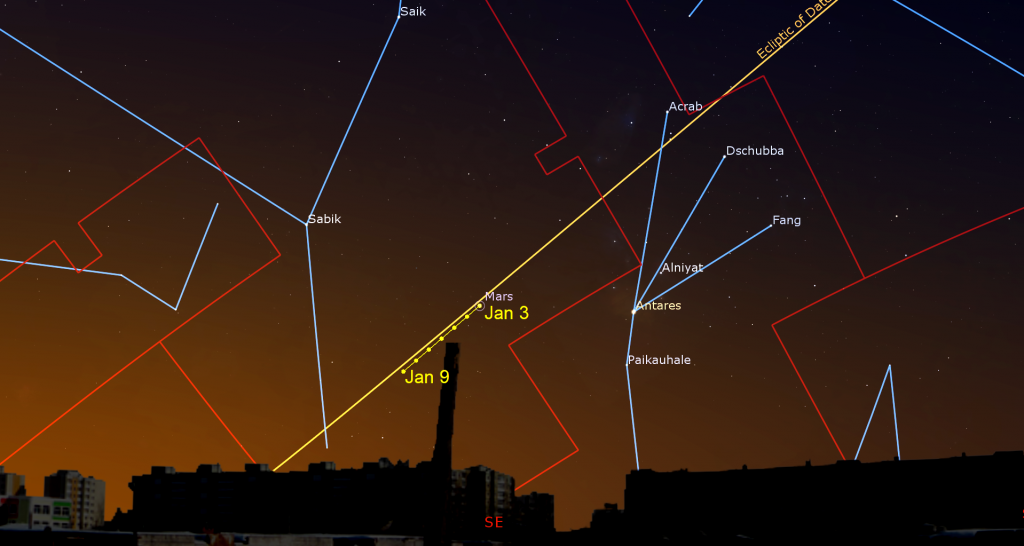

Early risers can watch for Mars, which will continue its year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. Mars will rise just before 6 am local time. You might spot the magnitude 1.5 planet shining low in the southeastern sky, to the left of its rival, the bright star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion) until about 7 am local time. From Monday to Sunday, the two ruddy dots will increase their separation from 6.5° to 10°. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

Deep Sky Suggestions

The waxing moon won’t flood dark evening skies worldwide with very much light until after Thursday, granting us several nights to view fainter deep sky delights, such as the Orion Nebula (also known as Messier 42). I wrote an in-depth tour of Orion (the Hunter) last January here. I toured Taurus (the Bull) here, and the treats in Auriga (the Charioteer) here. All three constellations are over in the eastern sky during evening, and they are loaded with treasures because the winter Milky Way runs through them. They all have sights to see with unaided eyes, binoculars, and backyard telescopes.

The same stars and constellations shine on the same dates every year. The moon and planets change their position, though – so ignore any mentions of the bright planets.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Wednesday evening, January 5 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month presented by me, and two talks about astrophotography. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds and Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 18 at 3:30 pm EST. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!