Mercury joins Jupiter at Sunset, a Waning Moon Leaves Evening to Join Venus at Dawn, Letting us Linger in Auriga!

This long exposure image by Steve Cannistra covers 4 degrees (8 full moon diameters) left-right. It shows the rich nebulae that lurk in the centre of Auriga’s ring of bright stars, especially the Flaming Star Nebula (top left). This image was APOD for Feb 24, 2012. More of Steve’s images can be viewed at http://www.starrywonders.com/

Happy 2021, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 3rd, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will vacate the evening sky for observers the world-over this week – allowing us to explore the delights of winter constellation like Auriga, the Charioteer. While Mars and Uranus are easy evening planets, don’t miss your last chances to see still-close-together Jupiter and Saturn, with Mercury, after sunset, and bright Venus before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This week, the moon will be waning in phase and rising late – leaving evening skies around the world delightfully dark for skywatchers. Tonight (Sunday) our “natural night-light” will rise at about 10 pm local time among the stars of Leo (the Lion), shine prettily in the southwestern sky before dawn, and then remain visible on Monday morning when its slightly gibbous form will shine in the lower part of the western sky. You can view the daytime moon in your binoculars or telescope if you take care not to aim your optics anywhere near the sun. Parental supervision is a necessity here.

From Monday night to Thursday morning, the moon will cross Virgo (the Maiden). When the moon reaches its third quarter phase at 2:37 am EST (or 09:37 Greenwich Mean Time) on Wednesday morning, it will be half-illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn sun. Third quarter moons are positioned ahead of the Earth in our trip around the sun. About 3½ hours later, Earth will occupy that same location in space.

The word “quarter” refers to how much of the moon’s monthly orbit it has completed – measuring from new moon. At first quarter, the moon is 90 degrees away from the sun in the sky – and follows the sun down in the west about six hours after sunset. Upon completing the second quarter of its orbit, the moon is opposite the sun in the sky, or opposition. You know that phase as full moon. About a week after full, the moon will complete three-quarters of its orbit. At third quarter the moon is once again 90 degrees from the sun in sky – but at this phase it rises in the east about six hours before the sun. Some people refer to that phase as last quarter, but that’s not quite accurate. When the moon meets with the sun a week later, completing one orbit, wouldn’t that actually be its “last quarter”? Don’t worry if you’re used to saying last quarter instead of third quarter – I’m guilty of it, too.

On Friday and Saturday morning, the waning crescent moon will pass through the stars of Libra (the Scales). Before sunrise on Sunday morning, January 10, look for the pretty sight of the moon’s slim crescent shining to the upper right (or celestial west) of the very bright planet Venus. The bright, reddish star Antares, the angry eye of Scorpius (the Scorpion) will sit a palm’s width to the moon’s right. Take a photograph!

The Planets

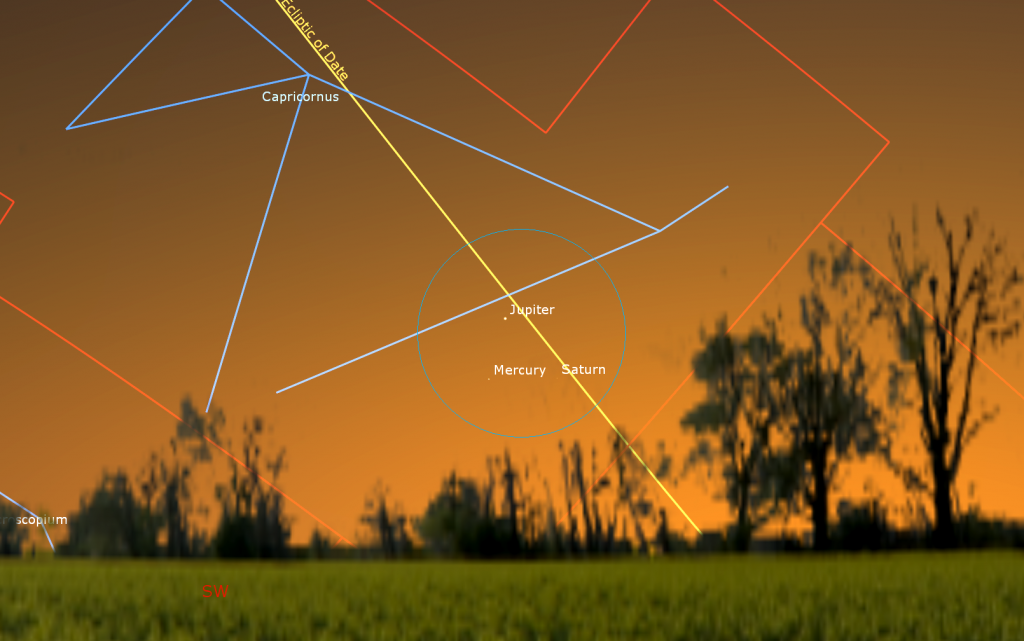

It’s still possible to enjoy Jupiter and Saturn after sunset this week, but they’ll be very low in the southwestern sky. After the so-called great conjunction, much brighter Jupiter has traded places with Saturn. Jupiter, now on the upper left of Saturn, is traveling eastward along the ecliptic faster than the more distant ringed planet – so their separation will steadily widen until they become lost in the sunset’s glare in a week or so. If you live at a mid-northern latitude, you can start to look for Jupiter at about 5 pm in your local time zone. Once located, seek dimmer Saturn sitting about a thumb’s width to the lower right (and widening every night). The planets will set by about 6:15 pm local time.

For observers living closer to the equator, the ecliptic will be near-vertical, so those planets, although still low in the west, will be positioned in the sky above the sun and will be surrounded by darker sky until they set.

From January 9 to 12, the planet Mercury will climb past the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, which will be descending sunward. If you have an unobstructed view of the southwestern horizon, and no clouds there, you can start to hunt for Mercury from about Thursday onwards, especially after 5:15 pm local time. On Saturday, January 9 Mercury will sit just two thumb widths below (or 3 degrees southwest of) Jupiter – with Saturn offset to the right between them. All three objects will fit within the field of view of binoculars. On Sunday evening, the speedy planet will be higher – forming a small triangle with Saturn and Jupiter. The trio will easily fit into the field of view of binoculars – but ensure that the sun has completely vanished below the horizon before using them. The three planets will set at about 6 pm local time, an hour after sunset.

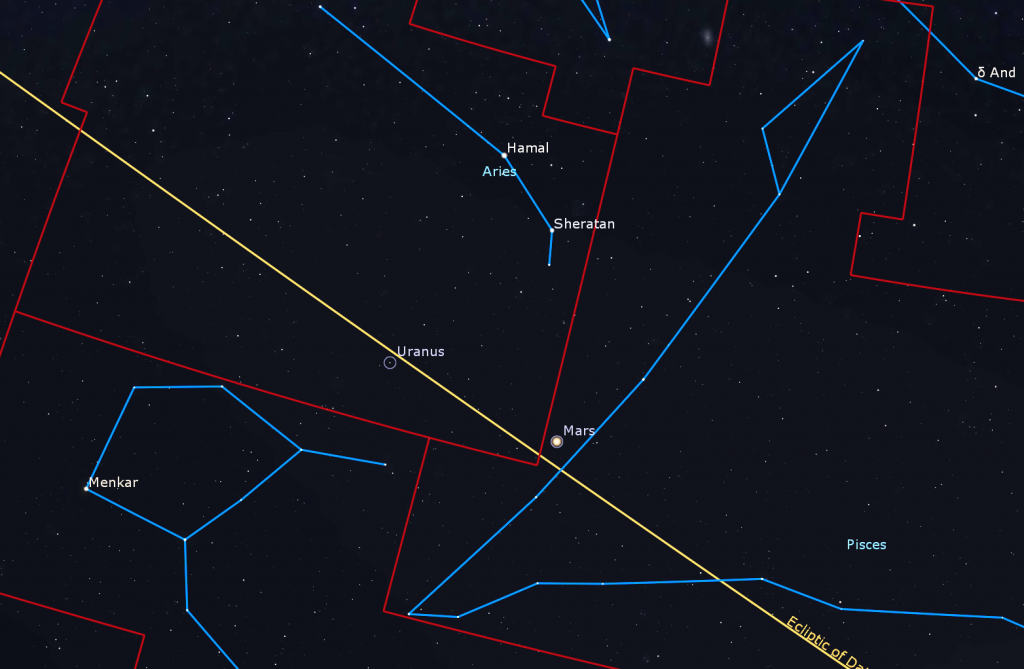

Mars is still a wonderful evening target – but it’s only about half as large as it looked at opposition back in mid-October, and a tenth as bright. This week, the reddish-tinted planet will already be shining high in the southern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point and best viewing position – more than halfway up the southern sky – at about 7 pm local time. Look for the V-shaped stars of Pisces (the Fishes) running up and down the sky to Mars’ right (celestial west).

Like Jupiter, Mars is steadily moving east along the ecliptic. On the nights around January 19, the red planet will pass very close to blue-green Uranus, which is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. At present, that region of the sky is more than a palm’s width to the left (or 8° to the celestial east) of Mars. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – especially when the bright moon is not in the evening sky.

Deep blue Neptune is also in the evening sky, but it’s much lower than Mars. After dusk it’s in the lower part of the southwestern sky, and descending. To see Neptune in your binoculars or telescope during this moonless week, look just to the upper left of the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The dim, magnitude 7.9 planet is sitting a finger’s width to the upper left (or 1.3 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii (or φ Aqr).

Venus has been gleaming brilliantly in the southeastern morning sky for some time now – but now it is sinking into the pre-dawn twilight. This week Venus will rise at about 6:30 am local time, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. Venus is traveling down (or celestial eastward) – from southern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) and into western Sagittarius (the Archer). While the sky is still dark, see if you can spot the bright, reddish star Antares in neighboring Scorpius (the Scorpion) sitting 1.5 fist diameters to Venus’ upper right.

Auriga the Charioteer

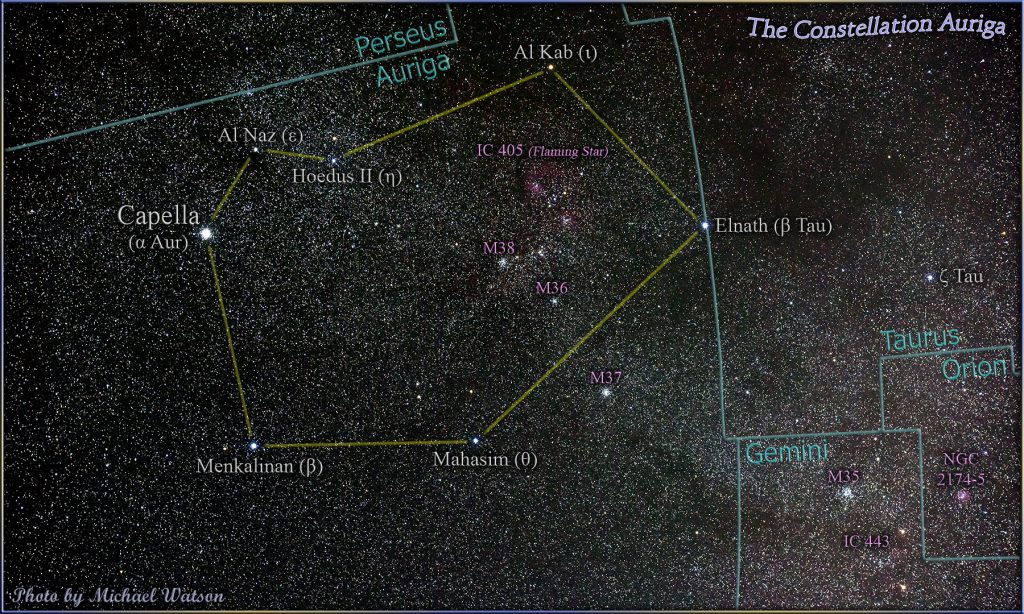

January evenings feature a group of bright and distinctive constellations that are easy to recognize with unaided eyes, and which make winter nights in the Northern Hemisphere worth waiting for. They are Taurus (the Bull), Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). Because the evening skies will be nice and dark this week and next, I’ll guide you through the best sights to see in Auriga. In future Skylights, we’ll tour the other three constellations.

Auriga is one of the original 48 constellations that the Greek astronomer Ptolemy recorded in his Almagest, which was published around 150 AD. Because the constellation is centred nearly 40 degrees north of the celestial equator, it is not visible at all from mid-southern latitudes, remains close to the northern horizon for observers at equatorial latitudes, and is circumpolar for much of Canada and other northerly latitudes.

Auriga’s brightest stars form an elliptical shape measuring about two fist diameters (17 degrees) north-south by about one fist diameter (12 degrees) east-west, with the very bright star Capella near its the northern end. Auriga’s southernmost bright star is shared with Taurus (the Bull), marking that critter’s northern horn tip. The official International Astronomical Union (IAU) boundary of the constellation spans 28 by 36 degrees of the sky. Perseus (the Hero) borders Auriga on the west (to the right for Northern Hemisphere observers). The twins of Gemini are on Auriga’s eastern boundary – sharing it with the dim constellation Lynx above them. The lesser-known, dim constellation of Camelopardalis (the Giraffe) occupies the sky to Auriga’s north.

The charioteer has been depicted in several ways over the years. It seems logical that the large, boxy ring of stars represents the chariot, and Capella represents the driver. Three medium-bright stars form a narrow triangle just south of Capella. Nick-named the Kids, they are said to represent an adult goat on his shoulder, and two kids under his left (western) hand. His right (eastern) hand holds the reins. In other stories, Capella is the adult goat and the three stars are her kids. The goat motif may have arisen before Ptolemy when the Mesopotamians saw the main stars of Auriga as a curved shepherd’s crook tending the little flock of stars.

In Greek mythology, several stories have been linked to Auriga. He was the Greek hero Erichthonius of Athens, who was the son of Hephaestus, and was raised by the goddess Athena. Erichthonius invented the four-horse chariot, created in the image of the Sun’s chariot, which he used in battle to become the king of Athens. Zeus raised him into the night sky in honor of his ingenuity and heroic deeds. He may also have been Hermes’s son Myrtilus or Theseus’s son Hippolytus, both well-known charioteers – or Bellerophon, the original rider of Pegasus.

In early evening during January, Auriga is halfway up the eastern sky, with Capella at the top left of the ring. By 11 pm local time, the constellation will ascend to the zenith – the best time to view its deep sky treasures. (More on those below.) Note that Auriga is visible during much of the year in Canada – but its rotation around the North Celestial Pole means that its orientation varies a lot.

Capella (Latin for “she-goat”), which marks the charioteer’s left shoulder, is the 6th brightest star in the entire night sky. At 42 light-years from Earth, Capella is a multi-star system. Its brightest components are yellow G-class stars similar in temperature to our sun, but larger and brighter. Let’s tour the rest of Auriga’s main stars, moving clockwise from Capella.

Three finger widths to the right of Capella sits the magnitude 3 star Almaaz “the he-goat”. Almaaz is a distant and hot F-class star that emits nearly 47,000 times as much energy as the sun. It’s also an eclipsing binary system that dims by 1.0 magnitudes for a two-year interval every 27.1 years – perhaps because of a giant dust ring orbiting the star?! The other two Kid stars are Haedus I and II, or Zeta and Eta Aurigae. The lower (eastern) star is 200 light-years away, and the other star is 850 light-years distant.

Jumping 1.3 fist diameters to the right (or 13 degrees south), past the Kids, the next medium-bright star we arrive at is Al Kab or Hassaleh “the shoulder of the reins-holder”. This orange K-class giant star is brighter than it looks because interstellar dust is dimming it. A palm’s width below Al Kab is bright Elnath, the northern horn star of Taurus.

From Elnath, swing a fist’s diameter back to the left (celestial north) to Theta Aurigae. Theta is a hot A-class star located 173 light-years from us. An intense magnetic field around this star has herded elements like silicon and chromium into patches that appear and disappear as the star rotates every 3.61 days.

Our trip around Auriga’s ring ends with Menkalinan (“the shoulder of the reins-holder”). It’s also known as Beta Aurigae. This star resembles Sirius and Vega – but its greater distance from us (82 light-years) dims its apparent brightness compared to those beacons.

A medium-bright, magnitude 3.7 star named Delta Aurigae sits a fist’s diameter to the left (north) of Menkalinan and Capella. Some star charts show it as the pointed end of the chariot – or the driver’s hat. A line extended from Theta through Menkalinan and Delta points almost exactly at the true North Celestial Pole!

The outer rim of our Milky Way passes through Auriga – filling the right-hand (or southern) half of the ring with star clusters and nebulas. Several clusters are very obvious if you scan the constellation with binoculars from a dark location. Forming a large triangle midway between Al Kab and Theta, you’ll find the bright open star clusters Messier 38 to the left and NGC 1893 sitting three finger widths to the right – with Messier 36 below and between them. Two finger widths below the line connecting Elnath to Theta is the bright cluster Messier 37. There are several more clusters and nebulas to discover in Auriga.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, January 6 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include the Sky This Month (presented by yours truly), and talks about the giant Magellan Telescope, amateur telescope making. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on January 19, 2021. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!