The Moon Renewed, Mercury Moves Past Jupiter and Saturn, Mars Approaches Uranus, and Taurus Treasures!

This amazing composite image by Detlef Hartmann shows the continued expansion of the Crab Nebula Supernova Remnant (aka Messier 1) in Taurus over 10 years (Sept 29, 2008 through Sept 22, 2017). It spans about 0.1 degrees of the sky. In the heart of the nebula sits a rapidly rotating neutron star that emits radio waves. They sweep across our detectors 30 times per second light a fast lighthouse’s beam. The intense radiation causes the gas in the cloud to glow. Detlef’s original image can be viewed at Astrobin https://www.astrobin.com/327338/0/

Happy January, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 10th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics.You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon not return to the evening sky for observers the world-over until late this week – allowing us to explore the treats of Taurus, the Bull. Mars and Uranus are close together and high in the sky during the evening. Watch Mercury passing close to Jupiter and Saturn after sunset, and the moon next to bright Venus before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This week, the moon will transition from the pre-dawn sky, pass through its new phase, and then re-appear after sunset in the west – leaving the evening skies nice and dark for stargazing.

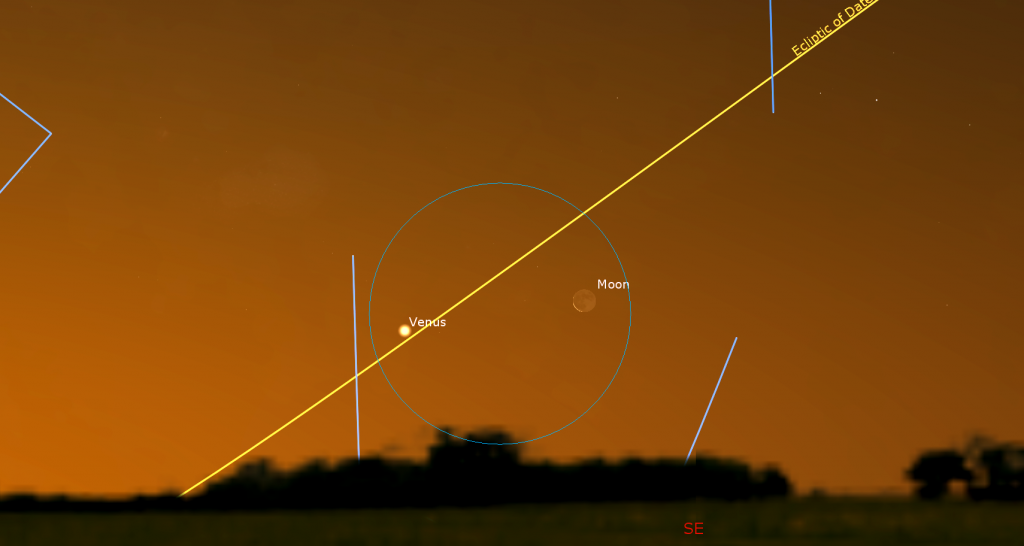

On Monday morning, you can look low in the southeastern sky before sunrise for the very slim crescent of the old moon shining a few finger widths to the right of bright Venus.

At midnight Eastern Time on Tuesday night (or 5:00 Greenwich Mean Time on Wednesday), the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes completely hidden from view for about a day.

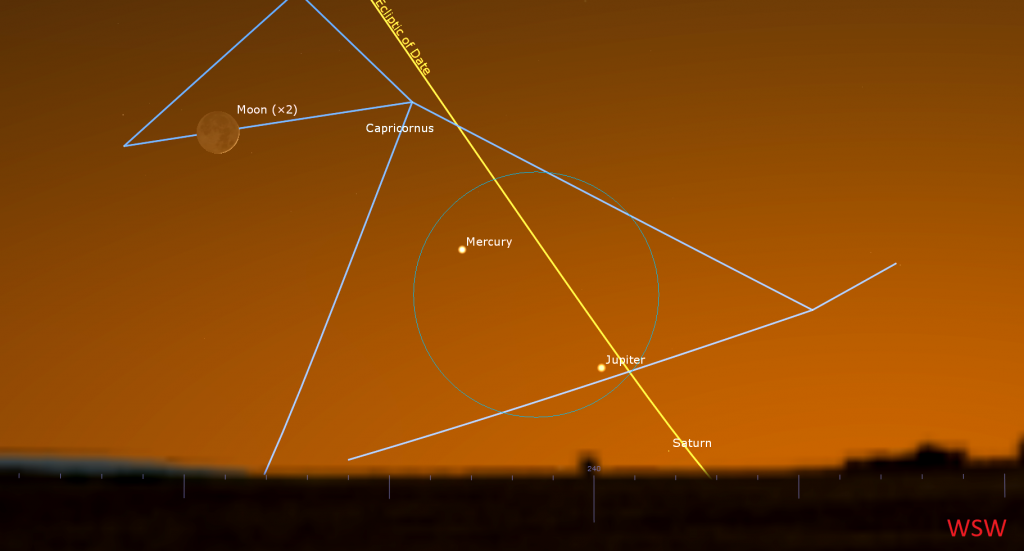

Immediately after sunset on Wednesday, sharp eyes and clear western skies might allow you to glimpse the young moon’s 1%-illuminated form over the southwestern horizon – but Thursday will be the day to look. The pretty, young crescent moon will be positioned a fist’s diameter to the upper left (or 10 degrees to the celestial southeast) of Jupiter, with dimmer Mercury midway between them – setting up a lovely photo opportunity! You’ll need an unobstructed southwestern horizon to catch a glimpse of Jupiter before it sets at 6 pm in your local time zone. Mercury will become easier to see just before it sets at 6:18 pm, and then the moon will follow them down at 6:35 pm.

The waxing crescent moon will begin to shine in a darker sky from Friday evening onward. Through the rest of this week, the moon will wax progressively fuller and climb higher in the western evening sky while it makes a trip through the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Keep an eye out for Earthshine or the “Ashen Glow”. When sunlight reflects off of clouds and the Pacific Ocean, it slightly illuminates the rest of the moon’s disk. Some call this phenomenon “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”.

The Planets

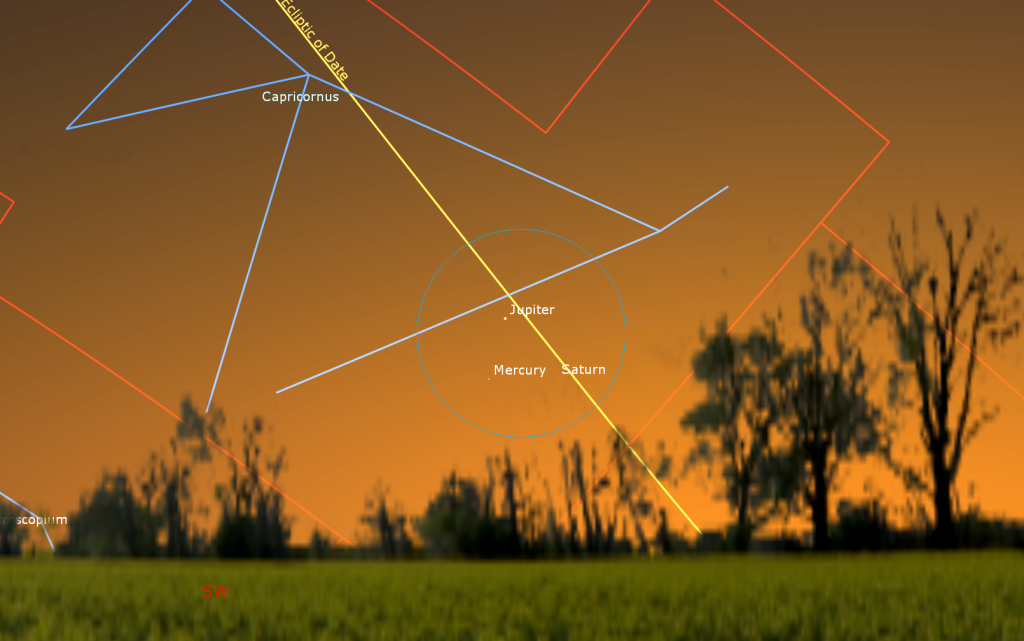

This is a big week for fans of Jupiter, Saturn, and Mercury – but they’ll be a challenge to see. From January 9 to 12, the eastward orbital motion of the planet Mercury will cause it to climb upwards past the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, which are being carried down and sunward by the 4-minutes-per-day westward shift of the sky as Earth orbits the sun. You’ll need an unobstructed view of the southwestern horizon, and no clouds there. West-facing high-rise dwellers will have an advantage!

Tonight (Sunday) the three planets will form a small triangle just above the southwestern horizon, with faint Saturn positioned two finger widths (2 degrees) to Mercury’s right and bright Jupiter positioned 2 degrees above them. Mercury and Saturn will be a challenge to see within the twilight – but you should be able to locate Jupiter first and then seek out the other two planets. The trio will easily fit into the field of view of binoculars – but ensure that the sun has completely vanished below the horizon before using any optics. The three planets will set at about 6 pm in your local time zone – about an hour after sunset.

For observers who live closer to the equator, the ecliptic will be near-vertical – so those planets, although still low in the west, will be positioned above the sun, and the sky around them will be darkening before they set.

The fun will continue! On Monday Mercury will climb to sit just a thumb’s width to the left of, and a bit below, Jupiter – with Saturn still to their lower right. On Tuesday, Mercury will move to sit two finger widths to Jupiter’s upper left (or 2 degrees to the celestial southeast). On Wednesday, Mercury will climb to sit 3 degrees to Jupiter’s upper left (and watch for that very young moon about 4 finger widths below Jupiter). And on Thursday, the moon will jump higher to form a rough line with Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn to its lower right (celestial northwest)! Take some pictures and share them with us!

Mercury will become more easily visible every night this week, especially between about 5:30 and 6 pm local time. In a telescope the planet will show a non-round shape.

Mars continues to be well-positioned for observing during evening – either as a bright, reddish “star” to your unaided eyes, or as a tiny round disk in telescopes. Mars is only about half as large as it looked at opposition back in mid-October, and one-tenth as bright. This week, the planet will already be shining high in the southern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point and best viewing position – more than halfway up the southern sky – at about 7 pm local time. Look for the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), brighter Hamal (magnitude 2.0) and Sheratan (magnitude 2.6) sitting a fist’s diameter above Mars (or 10 degrees to the celestial north).

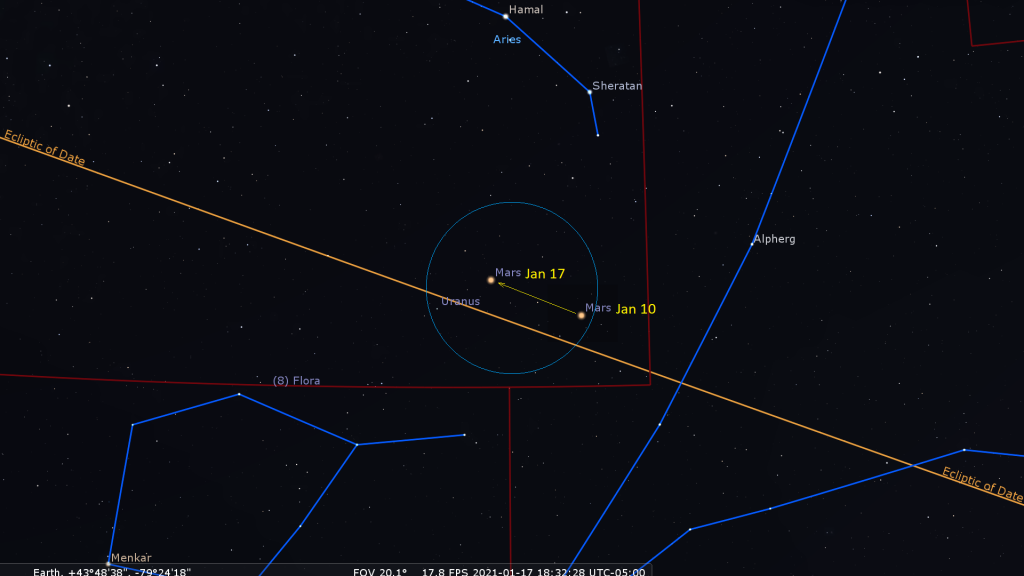

Mars is steadily moving east along the ecliptic. On the nights around January 19, the red planet will pass very close to blue-green Uranus, which is also among the stars of southern Aries. Tonight Uranus will be sitting a slim palm’s width to the left (or 5° to the celestial east) of Mars. By next Sunday, Mars will be only two finger widths from Uranus. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – especially when the bright moon is not in the evening sky. In a telescope, Uranus will resemble the stars near it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much and it will shine with a blue-green tint.

On Thursday, Uranus will stop moving compared to the distant stars because it will be completing a westward retrograde loop that began in mid-August. From Friday onwards, the planet will begin to move eastward again.

This week offers your last opportunity to see Venus gleaming low over the southeastern horizon for about an hour before the sun rises. Our sister planet has been sliding towards the sun for some time now, and only its intense magnitude -3.9 brightness has kept it visible within the dawn glow. On Monday morning, the old crescent moon will sit a few finger widths to the right (or 3-4 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Venus, making a nice photo opportunity when composed with some interesting scenery.

Treats in Taurus

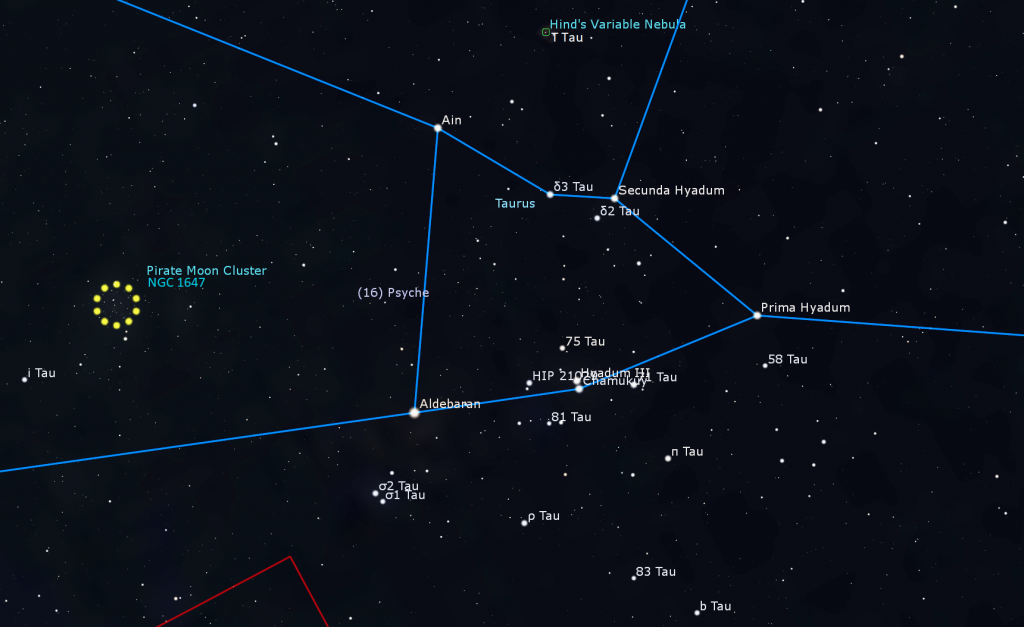

January evenings feature a group of bright and distinctive constellations that are easy to recognize with unaided eyes, and which make winter nights in the Northern Hemisphere worth waiting for. They include Taurus (the Bull), Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). The Winter Milky Way passes through those constellations – populating them with countless delights to view in binoculars or backyard telescopes on moonless nights. Because the evening skies will be nice and dark this week, I’ll guide you through the best sights to see in Taurus. Last week’s tour of Auriga (the Charioteer) is posted with sky charts and some photos of objects here. In future Skylights, we’ll tour the other two constellations.

The distinctive constellation of Taurus (the Bull) is perfectly placed for evening exploration in January. It is already halfway up the eastern sky when darkness falls and it crosses the sky for almost the entire night. Taurus contains many wonderful objects to observe in binoculars, and in small or large telescopes – from spectacular star clusters to a supernova remnant, and more. Let’s talk about some of its treats you’ll spy during a winter stroll, and others that make setting up your telescope on a cold winter evening worth your while.

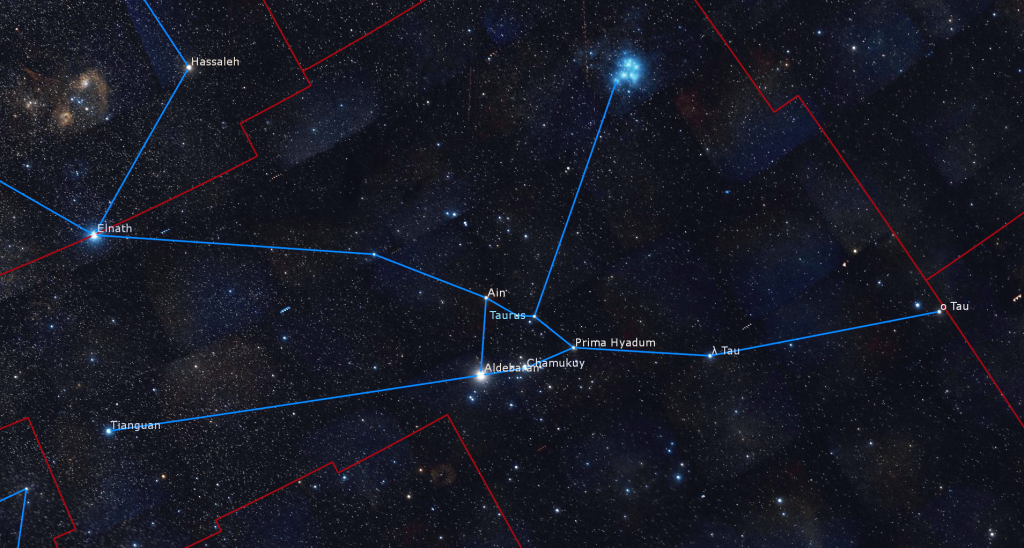

The constellation of Taurus is located on the ecliptic, and just north of the celestial equator, making it visible almost globally. With the dim constellations of Cetus (the Whale), Aries (the Ram), and Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) lying just to the west of it (on the right), Taurus’ much brighter stars make quite an improvement on them. Taurus also borders on Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). Being situation on Taurus’ left-hand (eastern) side, they rise later in the evening. To the north sits Perseus (the Hero), and to Taurus’ lower right (or celestial southwest) is the dim and winding constellation of Eridanus (the River).

Taurus’ boundary covers a square area of sky measuring about 3.5 fist diameters on each side – except for the southeast corner, which has been assigned to Orion. Taurus is dominated by several elements that combine to make the bull. A large, triangular arrangement of stars form the bull’s face. A very bright, reddish star named Aldebaran sits at the southeastern (lower left) vertex of the triangle, marking his baleful eye. He’s literally seeing red! Two medium-bright stars sitting 1.5 fist diameters to the lower left (east) of his face mark the tips of his horns. Well above the face, the Pleiades star cluster marks his hunched shoulders – and to the southwest, a handful of less prominent stars form his chest and forelegs. The rest of him is missing. When Taurus rises in the east, he is tilted sideways, with his horns down and legs extended – as if he’s charging the twins of Gemini. He doesn’t tilt upright until he enters the western half of the sky near midnight.

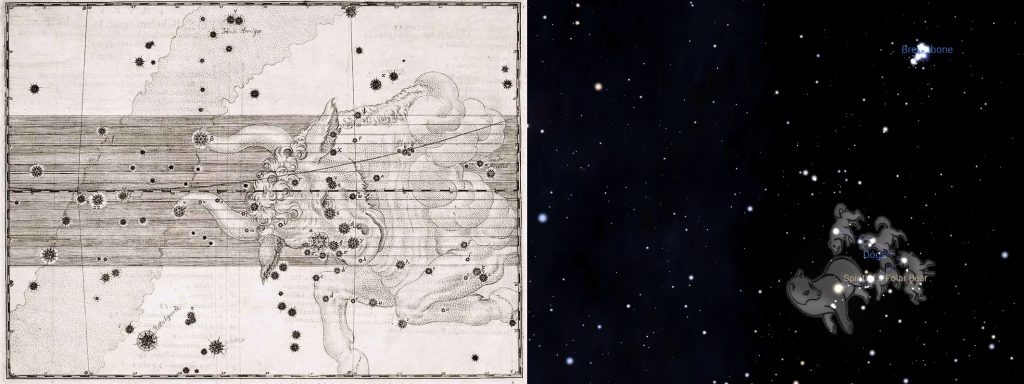

Taurus’ very distinctive shape has been recognized since ancient times. It was one of the first constellations to be described. At that time, the spring equinox occurred while the sun was in Taurus. (You can see this by setting an astronomy app’s date to noon on April 9, 2250 BC.) The bull’s strength and fertility were featured in ancient Babylonian and Sumerian myths and legends. In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the bull was sent to kill Gilgamesh (probably represented by Orion’s stars).

In Greek mythology, Taurus represented Zeus in disguise, seeking to abduct lovely Europa who was charmed by the animal’s power and beauty. It may also have been the Cretan Bull which Hercules slew during his twelve labours. In the Inuit traditions of the far north, Aldebaran represents a polar bear, and the rest of the stars in the triangle are dogs keeping him at bay..

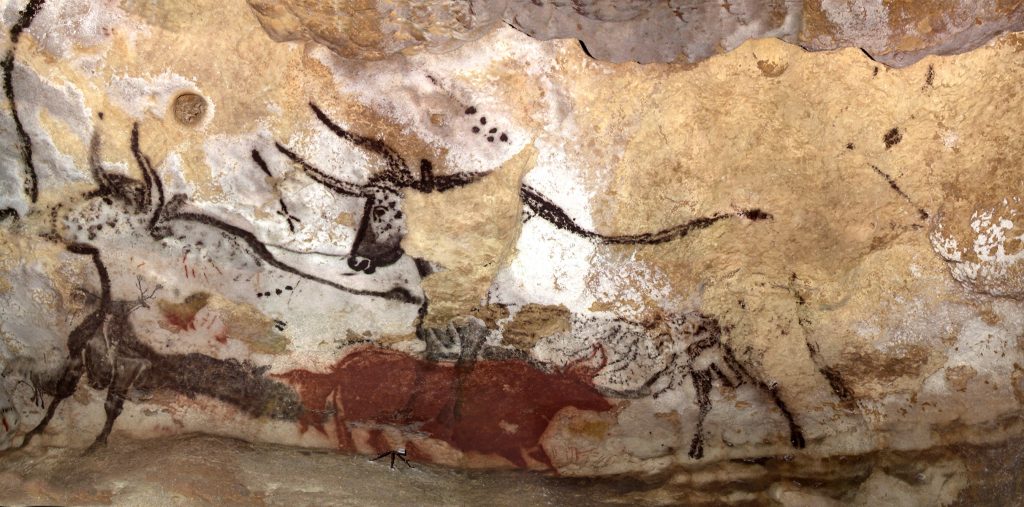

There is a remarkable theory that the stars of Taurus, and nearby Orion’s belt, were incorporated into the ancient paintings found on the Caves of Lascaux in Southern France. The paintings were created somewhere between 8,000 and 17,000 years ago. On the ceiling of the “Salle des Taureaux” or Room of the Bulls, are very large color paintings of horned bulls, one of which has dark facial spots approximating the Hyades, plus a grouping of six stars where the Pleiades should be, and a line of stars resembling Orion’s belt. Even the horns are placed where their stars are found. It’s wonderful to imagine early humans capturing the night sky for posterity!

This week, Taurus will rise in mid-afternoon local time, climb high into the southern sky around 9:30 pm, and then descend westward to set around 4:30 am local time. After dusk, you can find him by continuing the line formed by Orion’s belt westwards (upwards in early evening, or to the right later on) by about two outstretched fist diameters (or 20°) until you reach bright Aldebaran. If Orion hasn’t risen yet, you can look high in the east for the little cluster of blue stars of the Pleiades and find Taurus about a fist’s diameter below them (or 12° to the celestial southeast).

Taurus’ triangular face is actually one of the nearest open star clusters to us. Located only about 150 light years away from the sun, it’s called The Hyades. The cluster is named for the daughters of Atlas in Greek mythology, who were associated with rain when they wept for their slain brother Hyas. The cluster actually contains several hundred stars, with a half-dozen or so readily seen under moonless, suburban skies. It’s a lovely target to view in binoculars. Many of its stars are close pairs that astronomers call double stars. By the way, Aldebaran is not part of the cluster. It is less than half as far away!

Aldebaran, which means “follower” in Arabic because it chases the Pleiades across the sky, is the brightest star in Taurus. It’s an old orange giant located 65 light-years away from us. Somewhat cooler than our sun, it’s more than twice as massive and 44 times the sun’s diameter because it has exhausted its core Hydrogen and has swelled as it prepares to die. Aldebaran’s position near the ecliptic means that it is frequently occulted (passed over) by the moon and visited by the planets as they traverse their orbits.

The beautiful star cluster known as The Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, which sits about one and a half fist widths above the bull’s face, is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects. The Pleiades is made up of the young, hot blue stars named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. And those stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades. Only five or six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – plus their parent stars Atlas and Pleione huddled together at the east end of the grouping.

The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it, too makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – reflected light from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster in a telescope. In 1610, he published a sketch made at the eyepiece.

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have noted this object and developed stories around it. Many indigenous groups saw the Pleiades as the doorway in to the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. In Japan, it is called Suburu (スバル in katakana), and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

The star Elnath, or Alnath, which translates to “the butting one”, is an old, bright, hot blue giant star located 130 light-years away from our sun. It marks the bull’s higher (more northerly) horn tip. On the border of Taurus and Auriga (the Charioteer), it’s one of only two stars in the sky that are shared by two constellations. (The other is Alpheratz in Andromeda/Pegasus.)

The bull’s lower horn tip star is less bright, but is still readily seen by eye. It was once referred to as Shurnarkabti-sha-shūtū “the star in the bull towards the south”, but nowadays it’s simply called Zeta Tauri (or ζ Tau) or Tianguan. This star is a hot blue subgiant – 420 light-years away, but radiating 6,700 times the light of our sun. Zeta is a candidate to explode one day in a supernova burst – ironic since it sits very close to a supernova remnant, the Crab Nebula (more on this below).

The Hyades contains a number of nice double stars. Two degrees to the right of Aldebaran (towards the bull’s chin), look with unaided eyes or binoculars for the close-together pair of stars designated Theta 1 and 2 Tauri. The higher one is slightly more yellow. Also easy, on the opposite cheek are three widely spaced stars all designated Delta Tauri. Some apps label them as Hyadum II, Delta 2, and Cleeia or Delta 3. A finger’s width below Aldebaran, hunt with binoculars for the close pair of white stars named Sigma 1 and 2.

Here are a few more interesting objects to hunt for if you have a large telescope. The dim star 47 Tauri sits about a fist’s diameter to the lower right (or 9 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Aldebaran. It’s a close pair of unevenly bright yellow stars. Farther west, look for T Tauri, a very young star recently formed and still surrounded by some of its protostellar disk, often named Hind’s Variable Nebula. Lambda Tauri is a fairly bright star located five degrees to the lower right of the bull’s chin. This is an eclipsing binary variable star that dims in brightness for 1.1 days every 4 days because it has an orbiting dim companion star that blocks some of the main star’s light when it crosses between us and the star. Some apps mane it as Elthor “the bull”.

The supernova remnant now known as the Crab Nebula (or Messier 1) sits a finger’s width above Zeta Tauri. Nowadays, you need a very large telescope to see the remnant as a dim, fuzzy patch – but on July 4, 1054 AD Chinese astronomers recorded that the star that exploded to create the Crab Nebula shone bright enough to see it in the daytime for three weeks! Then it faded to become the brightest night time star for a few months. The object is about 6,500 light-years from the sun.

Here’s one more treat. A very red, magnitude 4.3 star named the Ruby Star (or 119 Tauri) sits 2.7 finger widths to the right of Zeta Tauri. It’s a variable star that pulsates every 165 days. There are even more sights to see in Taurus. You should be able to find it easily in binoculars.

The open star clusters NGC 1746 and NGC 1647 sit between the bull’s horns. A close-together pair of clusters NGC 1817 and NGC 1807 sit two finger widths below the mid-point of the line connecting Zeta Tauri and Aldebaran. The outer rim of the Milky Way passes just beyond Taurus’ horn tips, and that area will reward scanning with binoculars or telescope, too.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Friday evening, January 15 at 7 pm EST, The University of Toronto Aerospace Team (UTAT) invites you to attend their free online Women of Aerospace Speaker Series, featuring Natalie Panek of MDA speaking about her Aerospace journey. Registration details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on January 19, 2021. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!