An Absent Moon Leaves Bright Evening Planets, Awesome Auriga’s Kids, Comets, and Alternating Algol!

This wonderful image was captured around 8:30 pm EST on Saturday, February 11, 2023 by Andrea Girones from her backyard in Ottawa, Canada. It shows the green comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) as it slid past reddish Mars. The dusty tail is material left behind as the comet travels downwards (celestial southbound) in the sky. The field of view is about 4 degrees.

Hello, Star-lovers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 12th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be busy approaching the sun in the eastern predawn sky this week, leaving star lovers worldwide with the goddess of Love Venus and more bright planets in evening, some comets to view, and the bright stars of Auriga to appreciate. Read on for your Skylights!

Comet Update

Comet c/2022 E3 (ZTF) is still visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes, especially now that the bright moon had left the evening sky. That said, most people have been a bit underwhelmed by the views of the magnitude 7-8 object.

This week, Comet E3 (for short) will travel southward in the sky below the bright red dot of Mars. This evening (Sunday night) it will be positioned a finger’s width to the left of the midpoint between Mars and the bright reddish star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull). The stars of the large open star cluster named NGC 1647 will be just a thumb’s width below the comet, allowing them to share the view in both binoculars and in a low magnification telescope. On Monday night, the comet will slide past that cluster on the right (celestial east), so you have two nice photo opportunities to capture the pair.

On Tuesday night the comet will sit a thumb’s width to the left (or 1.5° to the celestial west) of Aldebaran, making it easy to find. The nearby double star Sigma1,2 Tauri will make another nice photo pairing. For the rest of the week, the comet will descend along the border between the bull and Orion (the Hunter). On the coming weekend, it will be located a few finger widths to the right (celestial west) of the top stars in Orion’s shield, Pi1 and Pi2 Orionis.

Comet C/2020 V2 (ZTF) is travelling in the northwestern evening sky between the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the bright star Almach in Andromeda (the Princess). Comet V2 is observable between dusk and late evening – but you’ll need a telescope and a relatively dark location to see it well. Comet V2 passed closest to Earth in early January. It will remain at about the same magnitude 10 brightness over the month as it dives through the plane of the solar system between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Its perihelion will be later this year.

This week Comet V2 will be travelling celestial southward – away from the star Ruchbah (Delta Cassiopeiae), which marks the peak in the shallower half of W-shaped of Cassiopeia (the Queen), and towards the bright star Sheratan in Aries (the Ram). Since the northern sky rolls around the celestial pole during the night, that motion translates to towards the left during evening – always in the direction away from Polaris.

This fainter comet is highest in the sky after dusk, and then it descends on the left-hand (western) side of Polaris during evening – so try to view it right after dinner. (Don’t forget to chill down your telescope, with its lens caps on, in a secure location for an hour or two ahead of viewing.) This comet is moving much more slowly – only about half an index finger’s width each night. The comet will pass near the medium-bright star Nembus from Monday to Wednesday.

I’ve seen reports that a third comet named C/2022 A2 (PanSTARRS) has brightened enough to see in a backyard telescope. It is descending the northwestern sky in early evening, travelling eastward along the border between Cepheus (the King) and Cygnus (the Swan), near Herschel’s Garnet Star and the Elephant Trunk Nebula (IC 1396). Observers located at mid-northern latitudes can alternatively view it in the lower part of the northeastern sky in the hours before dawn. I’ll post a sky chart here.

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light during the two weeks that precede the new moon on Monday, February 20. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic and the planet Jupiter. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. I posted a photograph of the phenomenon here.

The Moon

The moon will be absent from the evening sky this week, allowing stargazers worldwide to see the dimmer delights in the celestial sphere. Instead, our natural satellite will be sliding towards the sun in the predawn sky.

Night owls and early risers can see the half-illuminated moon shining in central Libra (the Scales) on Monday morning. The bright reddish star Antares and the up-down row of little white stars a fist’s width to the moon’s left are prominent features of Scorpius (the Scorpion) – the heart of the beast and its truncated claws, respectively. Observers in eastern Canada and the USA can watch the moon pass in front of (or occult) the medium-bright star Iota1 Librae between about 3:30 am and 4:33 am EST. If you live in Central America its nearby partner star Iota2 Librae will be occulted instead. Binoculars or a telescope will work well.

The moon will reach its third quarter phase at 12:01 pm EST, 9:01 am PST, or 16:01 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday, February 13. Third quarter moons rise around midnight in your local time zone, and then linger in the sky during morning daylight. This one won’t sit very high because the ecliptic is lower on February mornings. At this phase the moon is illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn Sun. Binoculars and telescopes will show the spectacular lunar terrain enhanced by near-horizontal rays of sunlight along the pole-to-pole lunar terminator. It’s interesting to see the same features we commonly view during evening lit from the opposite direction!

On Tuesday morning, Valentine’s Day, the slightly less than half-lit moon will hop east between Antares and the claw stars. After a visit with Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer) on Wednesday morning, the waning crescent moon will cross the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) on Thursday and Friday morning.

Before sunrise on Saturday, February 18, skywatchers will a clear sky and an unobstructed view towards the southeastern horizon can look low in the brightening sky for the sliver of the waning crescent moon positioned a generous palm’s width to the right (or 7.5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of magnitude -0.23 Mercury’s dot. The 5%-illuminated moon will be only two days away from new. Observers located at more southerly latitudes will see the pair much more easily – higher and in a darker sky – but the moon will be higher in the sky than Mercury there. Be sure to turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises. That will be our last chance to glimpse the moon until it re-appears after sunset next Monday.

Medusa Blinks

On mid-February evenings the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) is located high in the western sky. The easiest way to identify the constellation is to look for Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak, which shines midway between the W-shape of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the even brighter, yellowish star Capella in Auriga (the Charioteer) above it.

The second brightest star of Perseus (the Hero) is Beta Persei (β Per), better known as Algol, from the Arabic “Ra’s al-Ghul”, which means “the Demon’s Head”. Algol represents the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying. The star represented the god Horus in Egyptian mythology and was Rosh ha Satan “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew.

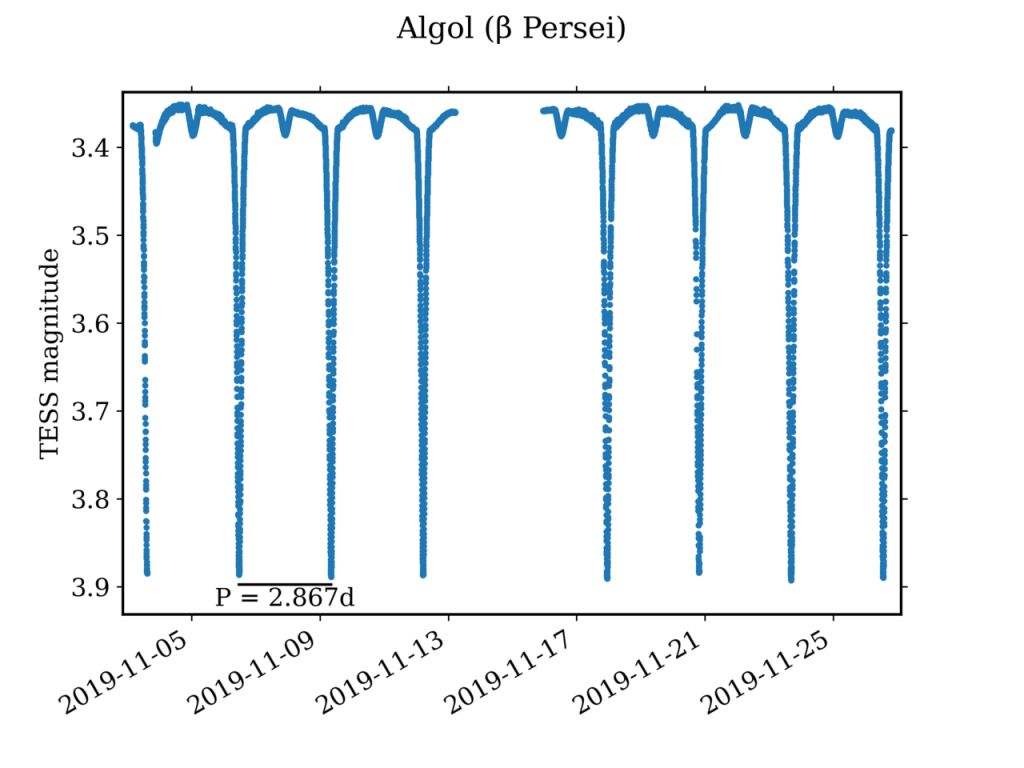

There’s a good reason for these scary associations. Ancient sky-watchers noticed that Algol is variable. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses behind the much brighter main star. Once the eclipse begins, the light we see steadily drops in brightness for five hours. Then it ramps up again during another five hours – until the eclipse is over. Algol is the archetype for all eclipsing binary star systems, and is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers.

The easiest way to monitor Algol’s variability is to note how bright that star looks compared to other, non-varying stars near it. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol shines at magnitude 2.1, similar in brightness to Almach, the bright star located a fist’s diameter above Algol (or celestial west) in Andromeda (the Princess). While dimmed, Algol shines at magnitude 3.4, about the same brightness as the star Gorgonea Tertia (or Rho Persei) located two finger widths to Algol’s right (or celestial south). Use your unaided eyes or binoculars to compare them.

On Thursday, February 16 at 7:39 pm EST, Algol will shine at its minimum brightness. Five hours later, at 12:39 am EST on Friday, it will have returned to full brightness. By then it will be perched just above the treetops in the northwestern sky.

The Planets

The bright planets Venus and Jupiter will be a breathtaking sight in the western sky after sunset this week. Even before the sky fully darkens, brilliant, magnitude -3.88 Venus will gleam in the lower third of the sky. It will set around 8 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope, Venus will display a waning, 89%-illuminated disk. To see its shape most clearly, look as soon as you can find it, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air.

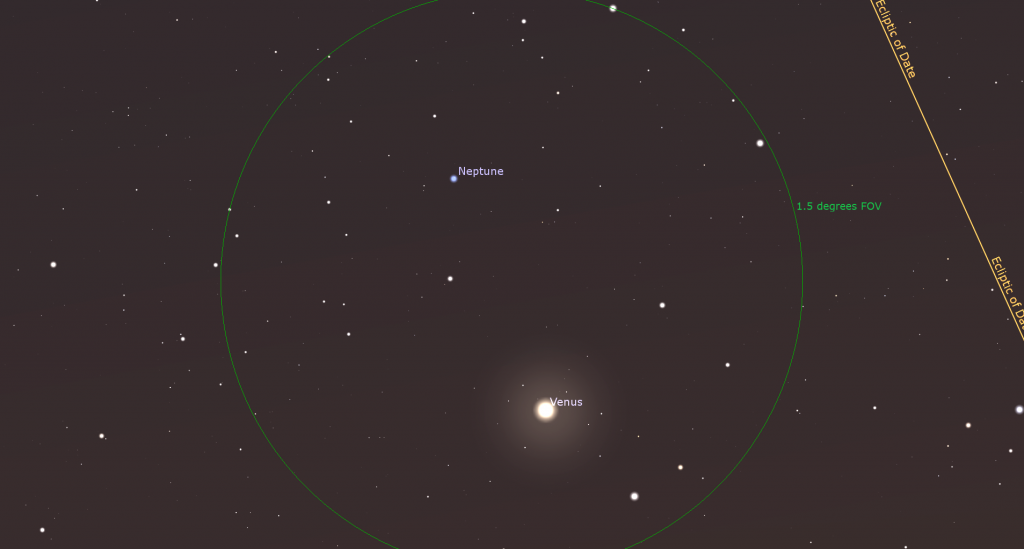

Jupiter will look noticeably less brilliant than Venus below it. The distance between the two planets will be shrinking daily because Jupiter is being carried sunward with the rest of the sky while Venus’ eastward orbital motion is moving it the opposite direction. They’ll kiss in a very close conjunction on March 1. Speaking of conjunctions, Venus will climb past magnitude 7.95 Neptune from Tuesday to Wednesday. On both nights, they’ll be cozy enough to share the view in a backyard telescope, but you can also try to use binoculars once the sky darkens. Although Venus will be 21 times nearer Earth than Neptune, it will outshine the remote planet by almost 12 magnitudes, or 54,000 times – making simultaneous telescope viewing of the pair a challenge.

Our window of time for clear magnified views of Jupiter in binoculars and telescopes will end in a few weeks. Jupiter will look best in a telescope as soon as you can spot it – while it is still reasonably high. It will sink lower through the evening and set in the west not long after 9 pm local time. Binoculars should be able to show a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will gather to the east of the planet on Wednesday, and then snuggle two on each side of Jupiter on Saturday evening.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, early Wednesday, Friday, and next Sunday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Monday evening, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere between 7:23 pm and 9:42 pm EST – but observers in the Central time zone will have a better view. On Friday evening, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator with the GRS from 6:58 to 9:05 pm EST. The events are widely visible over the western hemisphere. Just adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

Mars continues to become dimmer in the sky and smaller in telescopes each week – but you can still use a small, but good quality telescope and a high magnification eyepiece to see the largest dark markings on its rusty, 9.5 arc-seconds-wide disk. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

During early evening Mars will be positioned high in the southern sky above the stars of Orion (the Hunter) – and a slim fist’s width above the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of Taurus (the Bull). The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling 1.3 fist widths to Mars’ upper right (celestial west). Over the next weeks, you’ll be able to see Mars shift eastward above Aldebaran, and move a bit farther away from the Pleiades each night. For now, Mars will be highest in the sky around 7:30 pm local time (its absolute best telescope viewing time), and then descend westward to set during the wee hours.

The weak, magnitude 5.8 dot of blue-green Uranus is located nearly halfway from Mars towards Jupiter. You can also search a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 12.5° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), Omicron Arietis, and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet – within the same binoculars field of view. Those faint stars mark the hooves of the Ram. Uranus will be ideally placed for telescope-viewing, high in the southern sky, after dusk this week. It will set around 12:30 am.

The main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas is currently shining with a visual magnitude of 7.8, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescope. Again this week Pallas will still be situated low in the southern sky, in western Canis Major (the Big Dog), binoculars-close to the bright Little Beaver Cluster (Messier 41) and the medium-bright stars Mirzam and Nu2 CMa. Its motion shown in this chart will carry it higher and closer to Sirius as it gradually returns to eastward motion through the stars.

Auriga the Charioteer

February evenings feature a group of bright and distinctive constellations that are easy to recognize with unaided eyes, and which make winter nights in the Northern Hemisphere worth waiting for. They are Taurus (the Bull), Orion (the Hunter), Auriga (the Charioteer), and Gemini (the Twins). Because the evening skies will be nice and dark during this week and most of next, it’s a fine time to tour the interesting stars and the best sights to see in Auriga. Next week, we’ll tour another constellation.

Auriga is one of the original 48 constellations that the ancient Roman astronomer Claudius Ptolemy recorded in his Almagest, which was published around 150 CE. Because centre of the constellation is nearly 40 degrees north of the celestial equator, it is not visible at all from mid-southern latitudes, remains close to the northern horizon for observers at equatorial latitudes, and is circumpolar for much of Canada and other northerly locations.

Auriga’s brightest stars form an elliptical ring shape measuring about two fist diameters (17 degrees) north-south by about one fist diameter (12 degrees) east-west. The very bright star Capella sparkles near its northern end. The ring’s southernmost bright star Elnath is actually part of Taurus (the Bull), marking that critter’s northern horn tip. The official International Astronomical Union (IAU) boundary of Auriga spans 28 by 36 degrees of the sky. Perseus (the Hero) borders Auriga on the west (to the right for Northern Hemisphere observers). The twins of Gemini are on Auriga’s eastern boundary – sharing it with the dim constellation Lynx above them. The lesser-known, unremarkable constellation of Camelopardalis (the Giraffe) occupies the sky to Auriga’s north.

The charioteer has been depicted in several ways over the years. It seems logical that the large, boxy ring of stars represents the chariot, and Capella represents the driver. Three medium-bright stars form a narrow triangle just south of Capella. Nick-named the Kids, they are said to represent an adult goat on his shoulder, and two kids under his left (western) hand. His right (eastern) hand holds the reins. In other stories, Capella is the adult goat and the three stars are her kids. The goat motif may have arisen before Ptolemy when the Mesopotamians saw the main stars of Auriga as a curved shepherd’s crook tending the little flock of stars.

In re-creations of the Book of Fixed Stars published by pre-Islamic astronomer Abd al-Rahman al Sufi, Auriga’s ring of stars form his body and two fainter stars offset to its north mark his head. The bright stars of Auriga occupy only the western half of its IAU territory. The eastern section of the constellation doesn’t contain bright stars – but a smattering of stars that can be seen there under very dark skies and through binoculars represent the driver’s whip or flail. In 1789 Hungarian astronomer Maximilian Hell used stars from Gemini and Lynx to create a constellation named Telescopium Herschelii, in honour of William Herschel’s discovery of Uranus. A picture of it is here.

Several stories in Greek mythology have been linked to Auriga. He was the Greek hero Erichthonius of Athens, who was the son of Hephaestus, and was raised by the goddess Athena. Erichthonius invented the four-horse chariot, created in the image of the Sun’s chariot, which he used in battle to become the king of Athens. Zeus raised him into the night sky in honor of his ingenuity and heroic deeds. He may also have been Hermes’s son Myrtilus or Theseus’s son Hippolytus, both well-known charioteers – or Bellerophon, the original rider of Pegasus.

The ancient Chinese saw the main ring as the celestial emperor’s chariot. They connected groups of minor interior stars into upright triangle shapes that they named pillars or piers – meant to represent the hitching posts for the horses. The most westerly of them was the three “kid” stars. The Boorong of Australia combined stars near Capella and parts of Perseus to depict the Red Kangaroo Purra. The Inuit used Capella plus Castor and Pollux to form the Collarbones or Quturjuuk. For the Dakota / Lakota of North America, Capella marked the top of the Sacred Hoop “Can fleska wakan”, an asterism Europeans call the Winter Hexagon.

Viewed from mid-northern latitudes during evening in February, Auriga straddles the zenith – the best position to view its deep sky treasures through the least amount of intervening air. (More on them below.) Capella shines at the northern end of the ring – closer to Polaris. But the constellation’s path around the North Celestial Pole means that Auriga’s orientation varies a lot. To keep things simple, we’ll carry out our tour with celestial north up.

Capella (Latin for “little she-goat”) marks the charioteer’s left (western) shoulder. It is the 6th brightest star in the entire night sky. Capella is a multi-star system 42 light-years away from our sun. Its brightest components are yellow G-class stars similar in temperature to our sun, but larger and brighter. They orbit one another every 104 days at a separation of only 0.74 A.U, or about Venus’ orbital size. About 15 stars shine very close to Capella. Two are thought to be gravitationally bound red dwarf stars. The rest are just foreground or background stars sharing similar sky coordinates. Astronomers call them line-of-sight doubles.

Let’s tour the rest of Auriga’s main stars, moving clockwise from Capella.

Three finger widths to the lower right (or celestial southwest) of Capella sits the magnitude 3 star Almaaz “the he-goat”. Almaaz is a distant and hot F-class star that emits nearly 47,000 times as much energy as the sun. It’s also an eclipsing binary system that dims by 0.9 magnitudes for a two-year interval every 27.1 years – the longest period of that class of objects. That may be due to a giant dust ring orbiting the star!

Two more Kids stars shine two finger widths below Almaaz. The left-hand (eastern) Kid star is Eta Aurigae or Haedus II or Hoedus II. It shines at magnitude 3.15 and is a bluish B3-class star located 243 light-years away from us. The right-hand Kid is Zeta Aurigae. Its proper names include Haedus I, Hoedus I, Saclateni, or Sadatoni. The latter two may arise from the Arabic Al Dhat al ‘Inan “the Rein-holder” or Al Said al Thani “the Second Arm (of the charioteer)”. The word haedi is Latin for “kids”. Zeta Aurigae is another eclipsing binary system that dims by 4 magnitudes every 2.66 years.

Auriga’s ring continues 0.8 fist diameters below (or 8 degrees south of) the Kids, where we see the medium-bright star Iota Aurigae, or Al Kab or Hassaleh “the Shoulder of the Reins-holder”. This orange K3-class giant star, 494 light-years away, is more luminous than it looks because interstellar dust is dimming it to magnitude 2.65. The mass of this star is at the lower limit for supernovae and the upper limit for white dwarves.

A palm’s width below Hasselah is bright, white Elnath, the northern horn star of Taurus. It has the dual identity of Gamma Aurigae!

From Elnath, swing a generous fist’s diameter back up to the left (celestial northeast) to Theta Aurigae. Some apps use the name Mahasim, from al-miʽşam “the Wrist” (of the charioteer)”. Theta is a hot, white A-class star located 173 light-years from us. An intense magnetic field around this star has herded elements like silicon and chromium into patches that appear and disappear as the star rotates every 3.61 days.

A pair of medium-bright stars named Nu and Tau Aurigae shine together inside the ring to the upper right or celestial northwest of Mahasim. Both are about 200 light-years away from us and comprise one of the Chinese hitching posts with the similar star Upsilon Aurigae below them. Scan with your binoculars towards the Kids to find a neat triangle of magnitude 4.65 to 5.0 stars named Al Hiba I, II, and III, meaning “the Tent”. Those stars are also designated Mu, Lambda, and Sigma Aurigae. Lambda, the nearest to us at 40.7 light-years, resembles our sun. Mu is whitish, while orange Sigma is much farther away.

Our trip around Auriga’s ring ends with Beta Aurigae or Menkalinan (“the Shoulder of the reins-holder”). This magnitude 1.9, A2-class star resembles Sirius and Vega – but its greater distance from us of 81 light-years dims its apparent brightness compared to those beacons. A magnitude 4.3 star named Pi Aurigae is visible a short distance above Menkalinan. It’s a swollen red giant star located about 780 light-years away from our sun.

A medium-bright, magnitude 3.7 star named Delta Aurigae that sits a fist’s diameter to the upper left (celestial northeast) of Capella forms a triangle with Menkalinan. Some star charts show it as the pointed end of the chariot – or the driver’s head or hat. A line extended from Theta through Menkalinan and Delta points almost exactly at the true North Celestial Pole! Delta is an orange K-class star of magnitude 3.7. The Hindus call it Prijipati, the Lord of Created Beings.

In the “empty” eastern half of Auriga’s territory, binoculars will reveal a lengthy chain of stars all named Psi Aurigae. Each one has been assigned a numeral from 1 to 10, though number 10 actually sits within Lynx’ borders. They are also named Dolones I through Dolones X, all meaning prod or pike – the tool of the driver, perhaps?

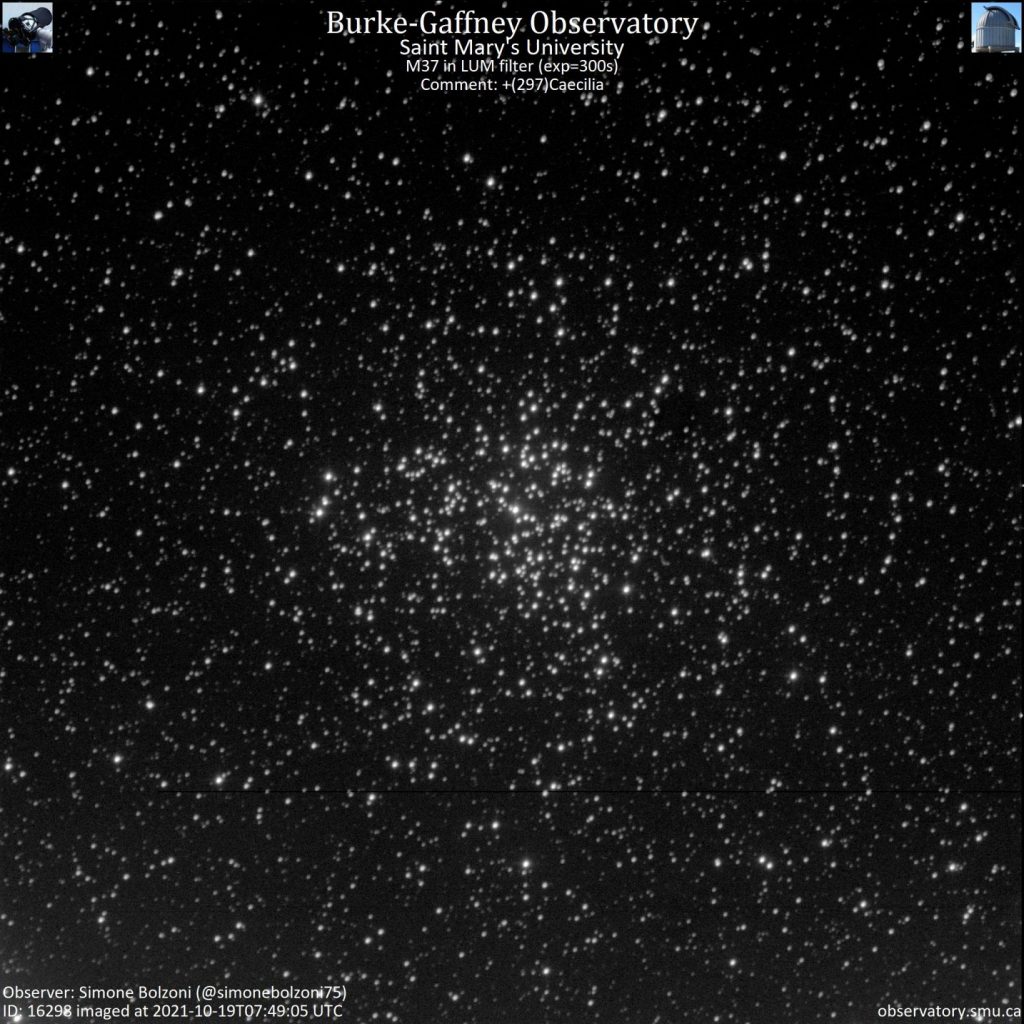

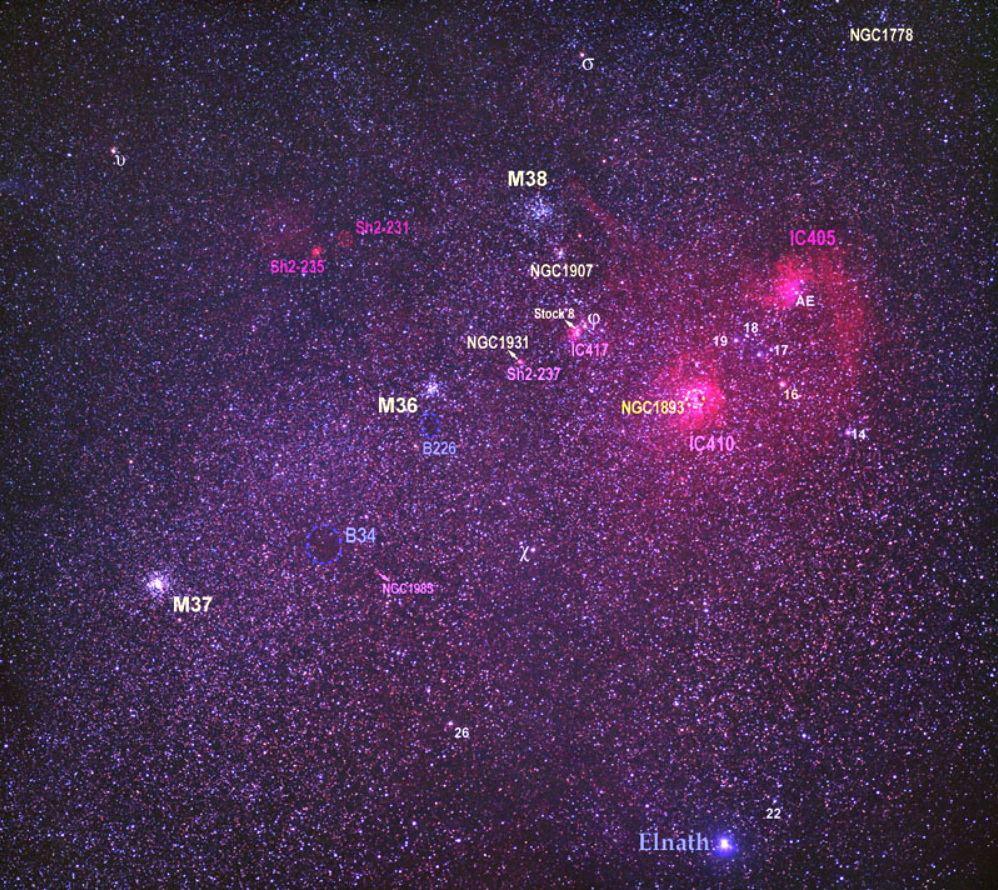

The outer rim of our Milky Way passes through Auriga – filling the lower (or southern) half of the ring with star clusters and nebulas. Several of them are very obvious if you scan the constellation with binoculars from a dark location. Search midway between Hassaleh and Theta for a large triangle of bright open star clusters. Messier 38 will appear between those bright stars. It’s large in size, and shows a loose scattering of stars, hence its nickname the Starfish Cluster. NGC 1893 will be three finger widths to its lower right. Its nickname is the Letter Y Cluster because of the pattern its stars form. Messier 36 will be positioned midway between Mahasim and Elnath, a thumb’s width inside the ring. It is nicely concentrated, with stars arrayed in curved chains. Messier 37 will sit the same distance, but on the outside of the ring. It is composed of a very dense collection of stars.

There are many more clusters and nebulas to discover in Auriga. Look around!

Delving into the Dippers

If you missed my tour through the dippers in the northern sky last week, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, February 15 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will Alex Innanen, MSc, PhD Candidate at York University. Their talk is titled 10 Years (and counting) of Curiosity. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, February 14 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on Auriga, the Charioteer, one of the oldest recorded constellations. His stars shine nearly overhead on February evenings. We’ll tell some tales of old, tour the Charioteer’s brightest and most interesting stars, and showcase its deep sky treasures – some observable by beginners and some that are best for big scopes and astro-imaging. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!