A Diminishing Moon, the Green Comet Passes Yellow Capella and Red Mars, Mulling Over Magnitudes, and Pondering Dippers!

This image by Michael Watson from September, 2017 shows the sliver of shadow that appears along its right-hand (eastern) limbs just hours after it is officially full.

Hello, February Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 5th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The bright waning minimoon will spoil our evening views of Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) and two other fainter ones until mid-week. Venus and Jupiter will blaze in the west after sunset, Mars will follow Uranus all night long, and Mercury will peek above the eastern horizon before sunrise. I spend some time demystifying the magnitudes system and tour you through the Dippers. Read on for your Skylights!

Comet Update

I was fortunate enough to spot Comet c/2022 E3 (ZTF) in my 10×42 binoculars last Thursday evening, only one day after its closest approach of Earth and therefore peak brightness. The bright moon and the lights on my suburban street made finding it a challenge. Once I did, though, I could tell it was a comet – but it would definitely be challenging for beginners to observe, even from rural locations. The tail was very subtle. I viewed it twice, 90 minutes apart. In that time it had moved a considerable distance compared to the surrounding stars!

From now on Comet E3 will sharply fade in size and brightness because of its steadily increasing distance from the warm of the sun and from Earth. You can play with a nice interactive 3D model of its orbital path here. Non-expert stargazers should be able to locate it easily when it passes a few bright objects in the sky this week. Look in early evening when it will be highest in the sky. Tonight and Monday try to stand where the bright moon is blocked by a roofline or tree. For the rest of the week, you can view the comet right after dusk, before the moon rises. Don’t expect to see what the media has promoted. New comets appear every few years, so let’s hope a better one comes along soon.

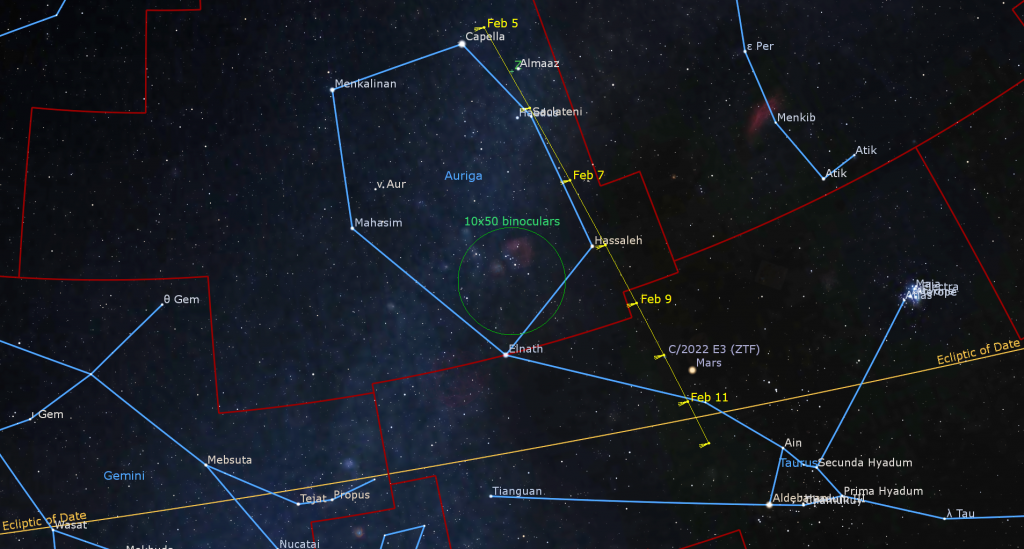

To find Comet E3 tonight (Sunday), take your binoculars or telescope outside after it gets dark and locate the very bright star that shines almost overhead. That’s Capella – the Goat-star in Auriga (the Charioteer). If you face east, the comet will be positioned about a thumb’s width above (to the celestial northwest) of Capella – in the direction of another very bright star Mirfak in Perseus (the Hero).

Comets are speedy! Every 24 hours the comet will glide almost a palm’s width (or 5°) southward – roughly in the direction of the bright reddish dots of Mars and the nearby star Aldebaran. On Monday night, February 6 the comet will travel close to the stars Haedus (Eta Aurigae) and Saclateni (Zeta Aurigae) – two of Capella’s three baby goat stars nick-named “the Kids”. Viewed in binoculars or the eyepiece of a backyard telescope at low magnification the comet will form a little triangle or crooked line with those two stars. On Wednesday night Comet E3 will pass telescope-close on the right-hand (celestial west) side of the bright star Hassaleh (Iota Auriga). Note that your astronomy apps and atlases might spell these star names slightly differently.

The comet will make for some nice astro-photos when it swings past Mars on Friday-Saturday, February 10-11. On Friday evening, the comet will located less than two finger widths above Mars when you face south, i.e., towards the celestial northeast. As the night wears one, Comet E3 will draw closer to Mars until they set below the northwestern horizon at about 3 am local time. On Saturday night, February 11 the comet will be positioned about a thumb’s width below Mars (or 1.6° to the celestial SSE). As Saturday night folds into Sunday morning, the diurnal rotation of the sky will swing the comet to Mars’ left while pulling its own motion will increase its distance from the red planet. Lucky observers in New Zealand, Australia, Eastern Asia, and the Pacific Ocean will see the comet pass only 1° from Mars on Saturday evening.

If you adjust the dates on the 3D orbit model link above, you’ll see that the comet will pass closest to Mars around mid-February. I wonder if the rover will get a photo of it. There’s no light pollution on Mars – and no bright moonlight! The comet will end this week positioned about midway between Mars and bright Aldebaran next Sunday night.

Another ZTF comet, named C/2020 V2 (ZTF), is in the northern sky, too – but on the opposite side of Polaris. It is travelling in the northwestern evening sky between the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the bright star Mirach in Andromeda (the Princess). Comet V2 is observable between dusk and late evening – but you’ll need a telescope and a relatively dark location. Unfortunately, the bright moon will limit its visibility until later this week. Comet V2 passed closest to Earth in early January. It will remain at about the same magnitude 10 brightness over the month as it dives through the plane of the solar system between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Its perihelion will be later this year. You can play with a nice interactive 3D model of its orbital path here.

This week Comet V2 will be travelling celestial southward – away from the star Ruchbah (Delta Cassiopeiae), which marks the peak in the shallower half of W-shaped of Cassiopeia (the Queen), and towards the bright star Sheratan in Aries (the Ram). Since the northern sky rolls around the celestial pole during the night, that motion translates to towards the left during evening – always in the direction away from Polaris.

This fainter comet is highest in the sky after dusk, and then it descends on the left-hand (western) side of Polaris during evening – so try to view it right after dinner. (Don’t forget to chill down your telescope, with its lens caps on, in a secure location for an hour or two ahead of viewing.) This comet is moving much more slowly – only about half an index finger’s width each night. The comet won’t be near any easy markers until the weekend, when it will be located below and between the medium-bright stars Nembus and Phi Persei. Images can try to capture the comet near the Little Dumbbell planetary nebula around mid-week.

I’ve seen reports that a third comet named C/2022 A2 (PanSTARRS) has brightened enough to see in a backyard telescope. It is descending the northwestern sky in early evening, travelling eastward along the border between Cepheus (the King) and Cygnus (the Swan). Observers located at mid-northern latitudes can alternatively view it in the lower part of the northeastern sky in the hours before dawn.

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light during the two weeks that precede the new moon on Monday, February 20. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic and the planet Jupiter. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year.

The Moon

For the first half of this week, a bright moon will shine in the evening sky worldwide. But we’ll get back to darker evenings by next weekend.

The Full Snow Moon occurred today (Sunday, February 5) at 1:28 pm EST, 10:28 am PST, or 18:28 GMT. Because this full moon will reach full only 33 hours after apogee, its greatest distance from Earth for this lunar month, it will look about 5% smaller than average – making it the opposite of a supermoon and the smallest full moon of 2023. When you see it on Sunday night, the moon will already have passed the anti-solar point on Sunday night in the Americas. Use your binoculars to detect that the craters along the moon’s left-hand (eastern) limb are partially in shadow – indicating the start of the lunar terminator’s slide westward as the moon wanes in illuminated phase. February full moons culminate very high in the night sky and cast shadows that are similar to the summer noonday sun. I wrote a lot about the February full moon and what to see on it last week here.

Tonight’s “full” moon will shine a short distance to the right (or celestial west) of the Sickle of Leo asterism. Its half-dozen medium-bright stars form the chest and head of the lion. They resemble a backwards question mark, with the very bright star Regulus at the bottom and the much less prominent star named Rasalas or Mu Leonis marking the top of the lion’s head about 1.4 fist diameters above Regulus. The sickle will be much easier to see from Tuesday onwards, when the moon will have moved away. Leo (the Lion) will dominate our evening sky in springtime.

On Monday night the 98%-full waning gibbous moon will hop east to form a triangle to the lower left (east) of Regulus and the star Al Jabhah or Mu Leonis, which marks the lion’s chest. Observers located in a swath of Earth that starts in the southeastern Arabian Peninsula and sweeps across southern Asia, part of Southeast Asia and most of Australia can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Al Jabhah around 05:30 Greenwich Mean Time on February 6.

The moon will continue in Leo on Tuesday night, and then slide along the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden) from Wednesday to Saturday. Use binoculars to spot the nice double star named Porrima twinkling above the moon on Thursday night. Observers in most of South America can watch the moon occult Porrima’s two close-together stars around 04:00 on February 10, which is late on Thursday evening local time. The bright whitish star Spica will shine to the moon’s lower right (or celestial south) on Friday night.

If you are an early riser, you can also look for the moon’s faded orb haunting the morning daytime sky all week long. Your binoculars might be strong enough to show you Spica in daytime on Saturday morning, when it will be positioned just a few finger widths to the moon’s lower right.

The Planets (and an aside about Brightness / Magnitudes)

The western evening sky this week will be dominated by the two brightest planets, magnitude -3.87 Venus and magnitude -2.17 Jupiter. Numerically, that’s a difference of 1.70. Visually, Venus will look 4.8 times brighter than Jupiter. Before we focus on the planets, let’s review what “magnitude” means.

The bright summertime star Vega is the reference point for the modern magnitudes or visual brightness scale. Magnitude values greater than 0.0 are fainter than Vega. Objects with negative magnitude values shine brighter than Vega. The measuring system is also logarithmic. A single integer jump in magnitude value (either up or down) translates to a 2.5 times difference in visual brightness. The reason for this rather non-intuitive system is that an ancient Greek astronomer named Hipparchus of Rhodes had assigned rankings to the 850 stars in a catalogue he published. His brightest ones were rank one, his less-bright stars rank two, and so on down to the limit of visibility with his unaided eyes, at rank six. Here’s an interesting online article about it from Sky & Telescope.

When modern astronomers began to measure stellar brightness numerically, it turned out that the brightest star was about 100 times more intense than the faintest star that human eyes can see (under ideal conditions). An astronomer named N.R. Pogson developed a mathematical formula where a magnitude 1.0 star shines 100 times brighter than a magnitude 6.0 star. After the magnitude -27 sun, the brightest night-time star Sirius has magnitude -1.45. Only solar system objects, the International Space Station, or a very rare local supernova, can outshine Sirius. Okay, back to the planet doings.

Venus will gleam above the rooftops immediately after sunset this week and remain in sight until after the sky fully darkens. The planet will be our “Evening Star” until July. In your telescope our cloud-shrouded sister planet will show a featureless, 90%-illuminated disk. To see its shape most clearly, look as soon as you can find it, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Venus will set around 7:45 pm local time. If the bright dot you are seeing is blinking or flashing, or shifting to the left or right, it’s an aircraft. Keep searching!

Next Tuesday, Venus will pass extremely close to 54,000 times fainter Neptune. In the meantime, the bright planet will decrease its distance below magnitude 7.95 Neptune from 11.5° tonight to only 3° next Sunday. This is happening because Neptune is being carried sunward with the rest of the sky while Venus’ eastward orbital motion is moving it the opposite direction. Venus will also kiss Jupiter on March 1.

Jupiter will pop into view in the lower third of the southwestern sky by the end of civil twilight (the sun 6° below the horizon). Your binoculars should be able to show the planet as a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another.

Jupiter will look best in a telescope as soon as you can spot it – while it is still reasonably high. It will sink lower through the evening and set in the west around 9:40 pm local time. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday, and during mid-evening on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Monday evening, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere between 4:45 pm and 7:05 pm EST. On Friday evening, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator with the GRS from 5:00 to 7:10 pm EST. The events are widely visible over the western hemisphere. Just adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

Tonight (Sunday), the tiny, blue speck of Neptune will be located midway between Jupiter and Venus. On each subsequent night, it will shift closer to Venus. Like Jupiter, try to view Neptune while it is higher right after dusk. The large asteroid named (4) Vesta, equal in brightness to Neptune, will be positioned about a palm’s width below Jupiter this week.

Since our closest approach back on November 30, the distance from Earth to Mars has increased dramatically. For that reason, the red planet has become dimmer in the sky and smaller in telescopes – but you can still use a small, but good quality telescope and a high magnification eyepiece to see the largest dark markings on its rusty, 10 arc-seconds-wide disk. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

During early evening Mars will be positioned high in the southeastern sky above the stars of Orion (the Hunter) – and just above the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of Taurus (the Bull). The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling a fist’s width to Mars’ upper right (celestial west). Over the next weeks, you’ll notice that Mars is shifting eastward above Aldebaran, and moving a bit farther away from the Pleiades each night. For now, Mars will climb very high in the south before 8 pm local time (its absolute best telescope viewing time), and then descend westward to set during the wee hours. Don’t forget that comet c/2022 E3 (ZTF) will pose next to Mars on Friday and Saturday.

The blue-green dot of Uranus is located nearly halfway from Mars towards Jupiter. You can also search a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or 12.5° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), Omicron Arietis, and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet – within the same binoculars field of view. Those faint stars mark the hooves of the Ram. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be ideally placed for telescope-viewing, high in the southern sky, after dusk this week. It will set around 1 am.

The main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas is currently shining with a visual magnitude of 7.8, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescope. This week Pallas will still be situated low in the southern sky, in southwestern Canis Major (the Big Dog), a few finger widths to the right of the line joining Sirius and the bright, rear paw star Adhara. Next Sunday, February 12, (2) Pallas will complete an oval retrograde loop that it began in November, 2022 and resume its regular eastward prograde motion, bringing it upwards (northwest) through the front legs of the dog and closer to Sirius. For the best views of it, wait until the asteroid has risen highest, at around 9:45 pm. While you are in the neighbourhood, seek out some of the many bright star clusters to the left (celestial east) of the big dog’s stars.

On Wednesday, the dwarf planet Ceres will cease its northerly motion across the stars of northern Virgo (the Maiden) and begin its own westward retrograde loop that will last until mid-May. In late evening on Wednesday, the magnitude 7.6 object will be located low in the eastern sky, several finger widths to the upper right (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial west) of the medium-bright star Vindemiatrix in Virgo. The bright, waning gibbous moon shining nearby from Wednesday to Friday will make finding Ceres harder, so consider waiting until the weekend for your search for this largest member of the Main Asteroid Belt. Imagers will be interested to know that Ceres will skirt the northern edge of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies this spring.

Mercury will be sliding sunward in the southeastern pre-dawn sky this week. Its position below the tipped-over morning ecliptic will make the planet harder to see for Northern Hemisphere observers, but a breeze if you live in the tropics or farther south. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will start around 6:45 am local time. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waxing, slightly gibbous phase.

Delving into the Dippers

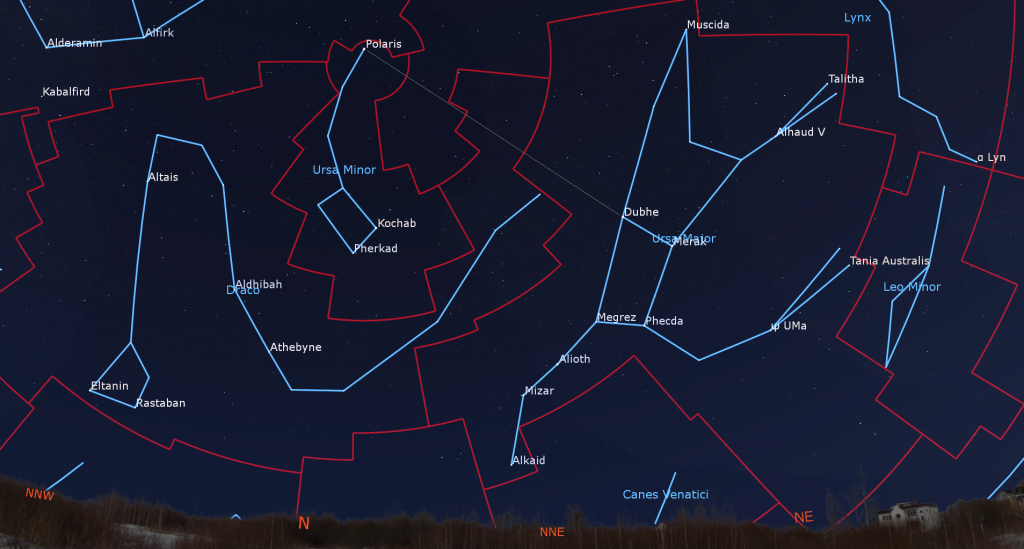

In the northeastern sky at this time of year, the Big Dipper is balanced upright on the tip of its handle in mid-evening. If you turn and face north, you’ll find it centred only a few fist widths above the horizon, and a little bit east (right) of north. By the wee hours, the dipper will climb to sit horizontal upside-down near the zenith.

The Big Dipper is not actually a constellation – it’s an asterism! In the UK, they call this star pattern The Plough. The ancient Chinese, who also saw a dipper in these stars, used the orientation of the Big Dipper to mark the seasons – when it stood upright at dusk, spring was around the corner.

The dipper’s seven bright stars are only a portion of a large constellation called Ursa Major (the Big Bear). Fainter stars located above and to the right of the dipper form the bear’s head and neck, and its front and rear legs. The bowl of the dipper looks a bit like a saddle on the bear’s back. The dipper’s handle doubles as the bear’s tail. But, wait a minute – real bears have stubby tails! Well, legends say the bear was swung into the night sky by its tail – stretching it!

On February evenings, the highest two stars mark the outer rim of the dipper’s bowl. Dubhe “doo-bee”, on the left, is a medium-hot, orange giant star located about 124 light-years from Earth. Hot, white Merak, to its right, is only 80 light-years from Earth. In the sky, the two stars are separated by 5.3°. Stretch your hand out in front of you and compare their separation to your palm’s width or various finger combinations. The name Dubhe is a shortened form of an Arabic expression that means “back of the Greater Bear”, while Merak means “the flank of the Greater Bear”.

Moving downwards, the star where the handle meets the bowl is named Megrez, which means “the root of the Greater Bear’s tail”. This star is the dimmest of the seven. It’s a medium-hot, white star located 81 light-years from us. The star at the lower right corner of the bowl is Phecda, from “thigh of the Greater Bear”. (Hmm – I think there’s a pattern here.) It, too, is a white star about 80 light-years away.

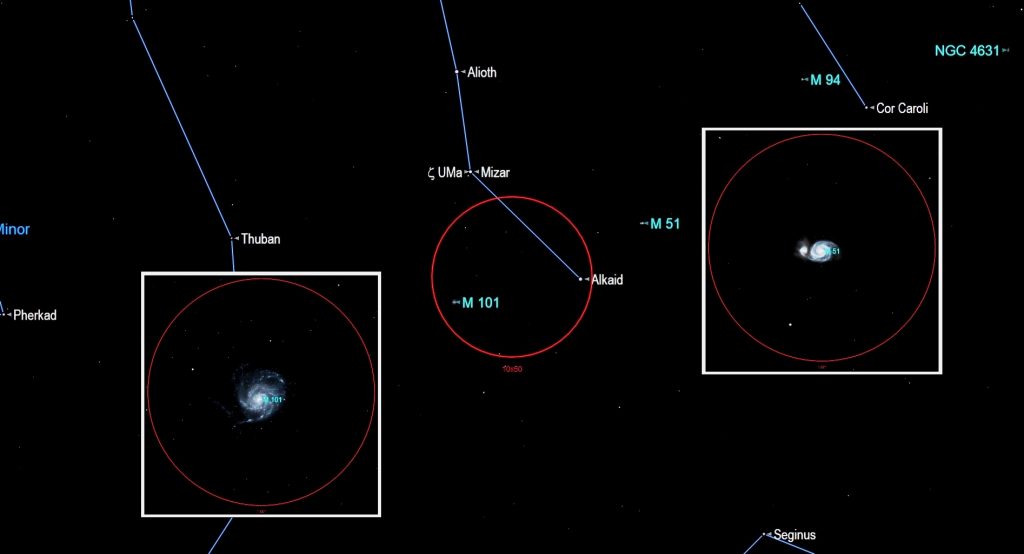

Astronomers believe that five of the stars in the dipper formed together about 300 million years ago, and are still travelling through space together as siblings – hence their similar distances from Earth. The three stars in the dipper’s handle (from highest to lowest) are Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid. Alioth is another of the “ bowl siblings”, while Alkaid is a slightly cooler, warmer coloured star located 104 light-years from Earth.

Mizar, the hot, white star at the bend in the handle, has a dim companion star named Alcor sitting just to the lower left of it. Most people can see Alcor without magnification. In ancient times, it was used to judge the eyesight of soldiers. In some cultures, Mizar and Alcor are called “The Horse and Rider”. In a small telescope, Mizar separates into a lovely double star with Alcor shining a short distance from them.

Ursa Major is located well away from the obscuring stars, gas, and dust of the Milky Way, allowing us to see into the distant universe in that part of the sky. The entire constellation is loaded with galaxies, including the spectacular Pinwheel and Whirlpool Galaxies.

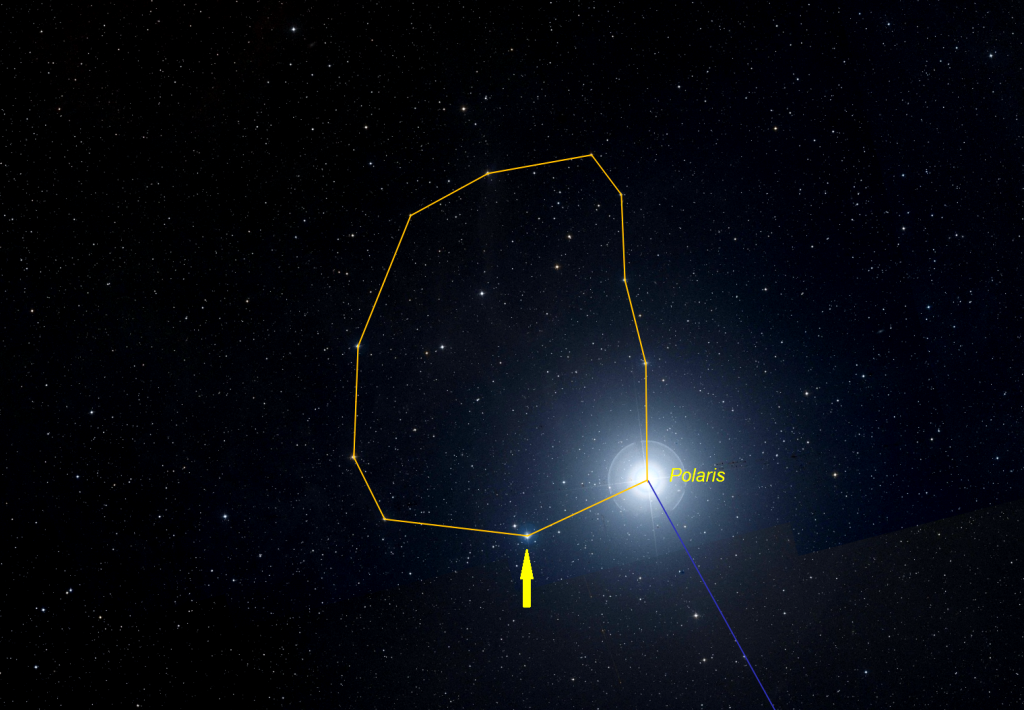

If you draw an imaginary line from Merak though Dubhe and extend it to the left (celestial north), the next major star you’ll encounter is Polaris, the North Star. Using your new sky angle measuring skills, you should come up with 29° from Dubhe to Polaris.

Polaris marks the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper. At this time of year at around 8 pm local time, the rest of the Little Dipper hangs downwards from Polaris, and curves strongly towards the Big Dipper. The two bowls pour into one another, with the tail stars of Draco (the Dragon), a large constellation that wraps around the Little Dipper, poking up between the dipper bowls.

The asterism of the Little Dipper also makes up the constellation of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). This little cub’s tail is stretched even longer than its larger parent. Other cultures have interpreted those stars as a dog or a wolf, which explains the lengthy tail much better! The indigenous Ojibwe people see the Big Dipper stars as Ojiig, the Fisher, which is a weasel-like animal. The Little Dipper is Maang, the Loon. There is a wonderful story about the way those animals saved the world!

The star at the outer edge of the Little Dipper’s bowl (and closest to the Big Dipper) is slightly dimmer than Polaris. This medium-cool, reddish star is named Kochab. The other five stars of the constellation may be too dim to see from the city, but binoculars will reveal them.

Polaris is located about one finger’s width from the north celestial pole – the point in space directly above the North Pole on Earth. As Earth rotates on its axis, all the stars rotate counter-clockwise (west to east) around Polaris. Polaris’ fixed location makes it especially useful for navigation – at least from the northern hemisphere, where it never sets. The point on the horizon directly below it is due north, and the star’s angle above the horizon gives you your latitude.

Contrary to popular belief, Polaris is a very modest looking star – it’s only 48th brightest in the night sky. Viewed through binoculars or a small telescope, Polaris also serves as the diamond in a crooked ring of dim stars. Coincidentally, the ring is a finger’s width across!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, February 14 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on sights to see along the winter Milky Way and some cold weather stargazing tips. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) is not visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!