The Waning Moon Moves Post-midnight, Leaving Lucky Aquarius and Plenty of Planets to Shine!

This image of the large, faint, and spectacular Helix Nebula was taken through the 16″ telescope owned by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and operated remotely from its location in Sierra, California. Ian Barredo re-processed the raw images to produce this award-winning result. The planetary nebula is the corpse of a star of mass similar to our sun located more than 500 light-years away. The image covers an area of the sky equal to the diameter of the moon. The star in the centre is the dead star’s hot core. the ring of gas are its expelled remains.

Welcome to October, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 1st, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

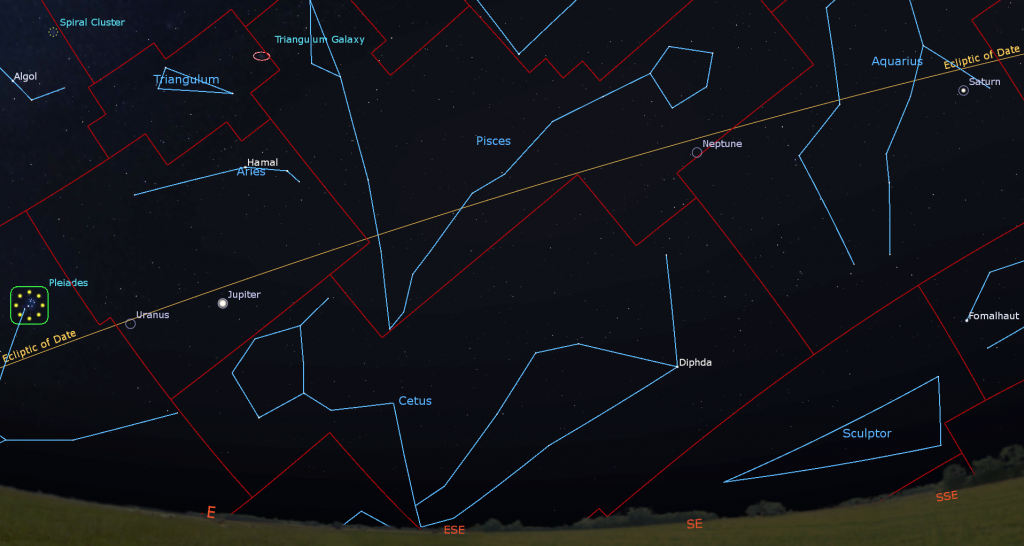

The bright harvest moon will steadily wane and rise later this week, eventually allow us to enjoy the faint lucky stars of Aquarius and the dim planets Uranus and Neptune, which are trailing bright Jupiter and Saturn across the sky every night. Mars and Mercury are lurking near the sun at dawn and dusk, while Venus will gleam every morning. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

Have you been enjoying the bright harvest moon this weekend? As I mentioned last week, the moon has been appearing above the eastern horizon only about 25 minutes later each night. But as our natural night-light wanes in phase over the course of this week its appearance will be delayed more and more. The earlier sunsets in the northern hemisphere will deliver dark skies before the bedtimes of junior astronomers, but the stars will be competing with moonlight until late in the week. So grab your binoculars and enjoy the shadowed craters along the curved terminator in the right-hand (eastern) half of the moon and the bright streaks of lunar ray systems around the craters on the broad western half.

Tonight (Sunday) skywatchers worldwide will be treated to a photo op when the bright, waning gibbous moon shines close enough to the very bright planet Jupiter for them to share the view in binoculars. The duo will rise in the east at around 8 pm local time and then cross the sky all night long, surrounded by the stars of Aries (the Ram) and the accompanied by the small, blue-green dot of planet Uranus. At sunrise on Monday morning, the moon and Jupiter will be positioned high in the western sky. By then the moon’s easterly orbital motion and the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift Jupiter to a palm’s width below the moon.

On Monday night the moon will hop eastward into Taurus (the Bull), where it will pose about a thumb’s width to the right (or ~2° to the celestial south) of the scattered stars of the Pleiades cluster, also known as Messier 45, the Seven Sisters, the Hole in the Sky, and Subaru. The cluster, which covers an elongated patch of sky several times wider than the moon, will be a challenge to see against the bright moon’s glare. Instead, hide the moon beyond the lower right edge of your binoculars’ field of view. Skywatchers viewing the scene later, or in more westerly time zones, will see the moon tucked in closer in below the cluster. The bright planet Jupiter will shine off to the moon’s upper right, while Uranus will be positioned about midway between the moon and Jupiter.

The moon will continue its trip through Taurus on Tuesday and Wednesday night. On Tuesday, the curved terminator on the moon will fall just to the right (or lunar east) of a large, curved escarpment on the moon known as Rupes Altai, making that feature especially easy to see with sharp eyes and through binoculars and telescopes. The cliff, which climbs up to 1 km above the lunar surface, is actually part of the rim of ancient Mare Nectaris. Its curve runs parallel to the edge of that large, dark basin, which will appear to its upper right (lunar northeast), though partly in shadow. Watch for the large crater named Piccolomini straddling the southeastern end of the cliff. Rupes Altai is highlighted every lunar month when the waxing moon is about five days past new and again when the waning moon is approaching third quarter.

On Thursday night the moon won’t clear the eastern treetops until nearly midnight. When it does, the large ring of stars forming Auriga (the Charioteer) will be sparkling above it, part of Orion (the Hunter) will be off to the moon’s right, and the constellation of Gemini (the Twins) will rise directly below the moon some time later. In just a month, you’ll be seeing those winter constellations climbing in the east at mid-evening!

The moon will officially complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Friday morning, October 6 at 9:48 am EDT, 6:48 am PDT, or 13:48 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will cross the sky for the rest of the night and then remain visible in the western daytime sky until early afternoon. The week of dark, moonless evening skies that follow this phase will be the best ones for stargazing, especially for observing fainter deep sky targets.

Early risers can enjoy the sight of the waning crescent moon dropping closer to very bright planet Venus in the eastern sky every morning from Friday until next Tuesday when they’ll pair up. Along the way the moon will cross through the rest of Gemini (the Twins) and then Cancer (the Crab). On next Sunday morning, the moon’s crescent will shine several finger widths to the upper left (or four degrees to the celestial north of) the large open star cluster known as the Beehive, Messier 44, and NGC 2632 – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. To best see the “bees,” which cover an area more than twice the moon’s diameter, hide the bright moon just beyond the upper left edge of your binoculars’ field of view.

The Planets

There are five planets in the evening sky nowadays – sort of. Mars is on the far side of the sun from us and looking about as small and as faint as it ever does. Although Earth’s orbital motion is shifting Mars closer to the sun every day, its own orbital motion is acting counter to that, delaying Mars’ conjunction with Sol until mid-November – like a salmon swimming against the current. For now, the red planet is lurking less than a palm’s width above the western horizon after sunset, heavily obscured by the increased intervening atmosphere and the bright twilight. If you live in the tropics, where Mars’ orbital plane will be close to vertical, you can spot the planet for a short time right after sunset. After it shows up in the eastern pre-dawn sky next spring, Mars will spend all of next year growing in splendor ahead of its next bright opposition in early January, 2025.

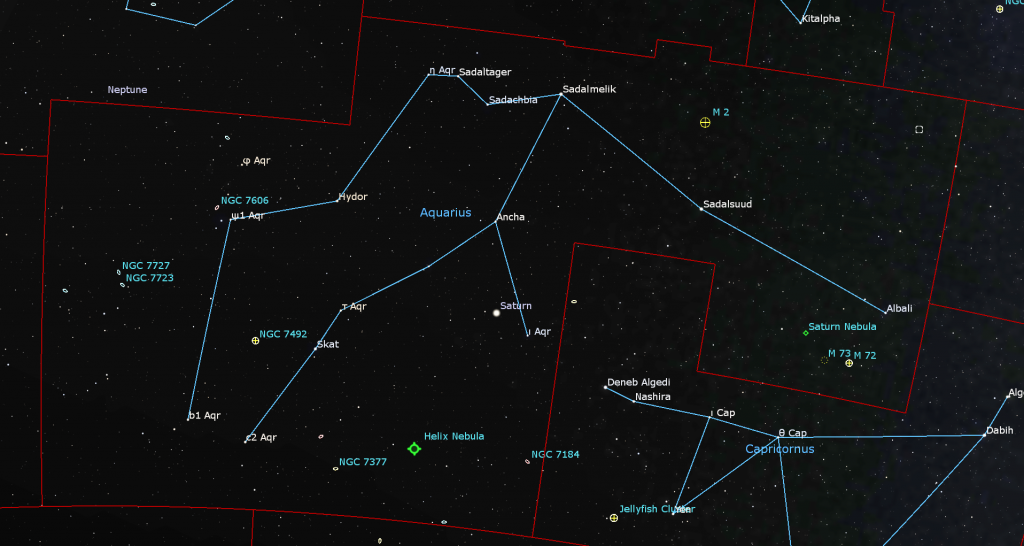

The rest of the planets will be easier to see. The medium-bright, yellow-tinted dot of Saturn will appear in the lower part of the southeastern sky during dusk, and then it will shine all night long as it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope while it is higher in the sky between 8 pm and 2 am local time. During evening, the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be shining to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle high above it, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be positioned a few fist diameters to the planet’s upper left. If you have an unobstructed southern view, the very bright star Fomalhaut or Alpha Piscis Austrini (the Southern Fish) will be shining two fist diameters below Saturn all year long.

Any size of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and faint belts of dark cloud that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from below Saturn (celestial southeast) tonight to the upper right of the planet (celestial west-northwest) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

This summer the ice giant planet Neptune, currently 795 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Recently past opposition for 2023, Neptune is still shining with a slightly enhanced magnitude of 7.8 and visible all night long in backyard telescopes. Good binoculars can show it, too, if your sky is very dark. Like Saturn, your best telescope views will come in the hours after 8 pm local time, when the blue planet is higher. Neptune’s star-like disk size is currently a mere 2.36 arc-seconds.

The very bright planet Jupiter, which currently outshines Saturn by about 21 times, will be rising around 8 pm local time this week. Good telescope viewing time will commence around 10 pm (and half an hour earlier than that with each passing week). Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will be shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. Jupiter will spend the night following Saturn across the sky and catching the eye of early birds while it gleams in the western sky at sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. Don’t forget that our moon will shine next to Jupiter tonight (Sunday).

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Monday, with Io’s black shadow on Thursday, and Saturday night. It’ll show in the wee hours of Monday, Thursday and Saturday morning. It’ll also appear before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday night, October 2, Europa’s small shadow will lead the Great Red Spot across Jupiter from 9:37 to 11:54 pm EDT (or 01:37 to 03:54 GMT on Tuesday). On Wednesday morning, October 4, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region with the spot from 3:24 to 5:30 am EDT (or 07:24 to 09:30 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again, behind the great red spot, on Thursday evening, October 5 from 9:53 pm to 11:59 pm EDT (or 01:53 to 03:59 GMT on Friday). (These times may vary by a few minutes.)

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus, which is following Jupiter across the sky this year, will be located a slim fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 8.6° to the celestial east), just inside Aries’ border with Taurus. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. This year, a pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (or Sigma and Zeta Arietis) will shine two finger widths above Uranus. Since they are easy to see in binoculars, they’ll be your guides.

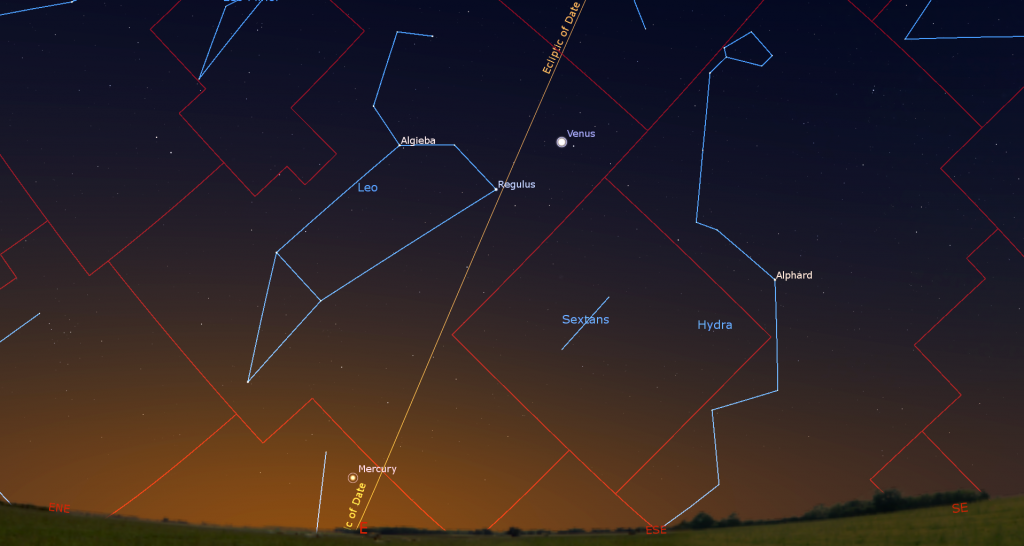

Venus will be blazing away in the eastern pre-dawn sky from now until January, climbing farther from the sun with each passing day. Viewed in a telescope this week, our sister planet’s disk will be shrinking in size and waxing in its crescent phase. Venus will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) at about 3:30 am local time. As I mentioned above, the moon will start dropping closer to Venus starting on the coming weekend.

Mercury will be shining just above the eastern horizon before sunrise this week, though it will be descending a little each morning as it swings sunward. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 90%-illuminated, waxing phase. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises. I’ll post sky charts for this week’s observable planets here.

The Water Constellations – The Lucky Stars of Aquarius

Autumn evenings feature a group of water-related constellations shining over the southern horizon. They aren’t very prominent – consisting mainly of dim stars – but the moonless skies later this week and next week will offer an opportunity to see them more easily. Despite their modest appearance, you will definitely have heard of them, because they straddle the ecliptic, and are therefore zodiac constellations.

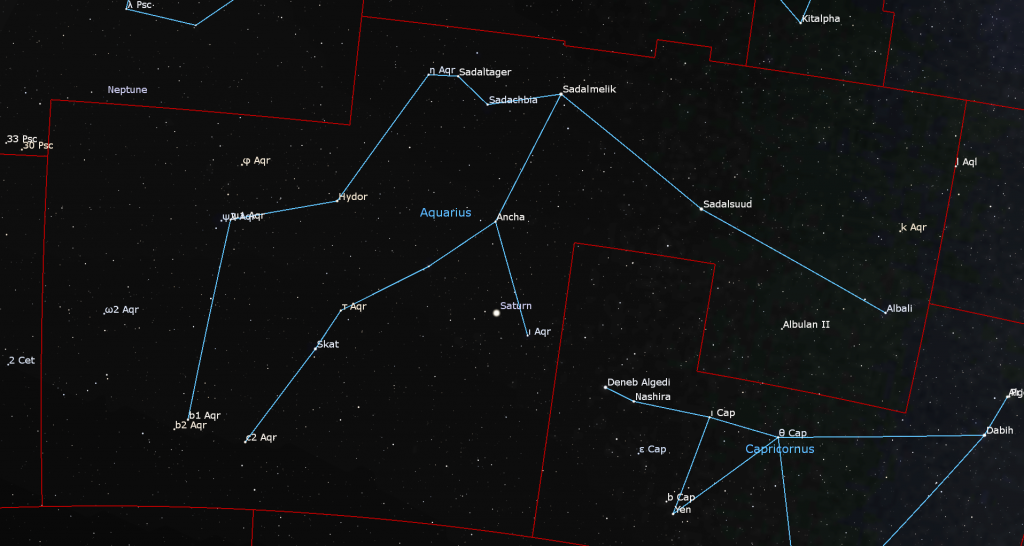

This year, Saturn has been the brightest feature of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), the second dimmest constellation of the heavens and the most westerly of the set, is Aquarius’ neighbour to the right (celestial west). Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) swims below (to the south of) Aquarius. On the left (east) you’ll find the fishes of Pisces perched (pardon the pun) above Cetus (the Whale).

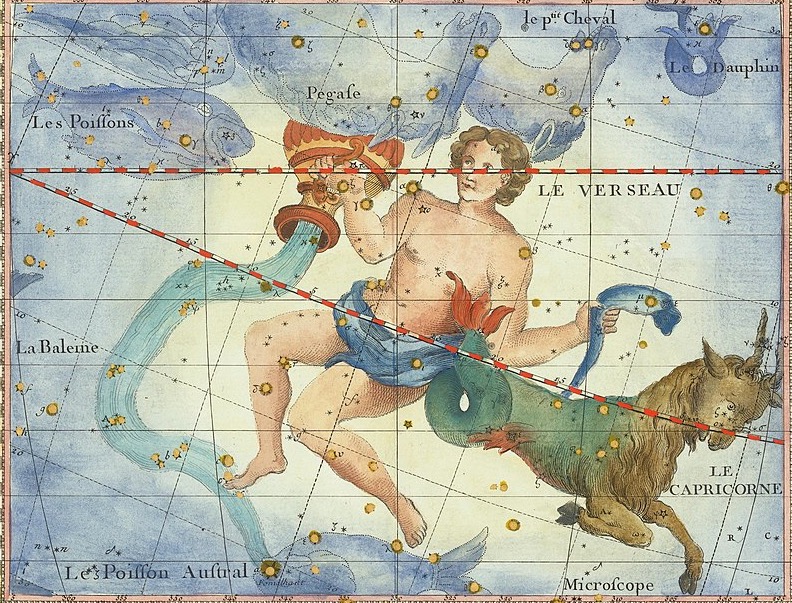

Aquarius is one of the oldest recorded constellations, probably because of its place on the ecliptic / zodiac and because it re-appeared in the morning sky at the time of year that brought the return of desperately needed rains and the flooding of the Nile in ancient Egypt. It certainly was not because of its stars. The constellation is composed of about 14 modestly-bright stars, most with visual magnitudes that are near the limit for suburban observers to see.

Aquarius spans an area that measures about 3.5 outstretched fist diameters wide by 2 diameters high (or 35 by 20 degrees). A section in its western half has been given over to Capricornus. Aquarius is traditionally depicted as a kneeling figure, facing east, who is pouring water from a vessel. A crooked horizontal string of stars represents his right arm outstretched towards the west. To their left are the stars of his bowed head and shoulders, and finally his left hand, which bears the jug. The jug is the most easily seen part of the constellation. Descending from that line is a loose chain of stars representing the flowing water and another chain representing his torso and legs. In some stories, those stars are Zeus pouring out the water of life upon the world. In others, the waters are those of the biblical flood, a story handed down from the Sumerians. The pre-Islamic Arabs envisioned the next-door Great Square of Pegasus as al Dalw, the water well. As we’ll soon see, the stars of Aquarius are “lucky”.

By the time the sky has darkened enough to see its stars in early October, Aquarius will be positioned in the lower part of the southeastern sky. For mid-northern latitude observers, Aquarius will reach its highest point due south, and centred midway between the southern horizon and the zenith, by 11 pm local time. Since it also touches the celestial equator, Aquarius will climb to nearly overhead for observers viewing it from near the Earth’s equator. That celestial real estate also means that Aquarius is visible from everywhere on Earth, except the northern polar region.

To help you find Aquarius, use the great square (or baseball diamond) of Pegasus, which sits much higher in the sky and to Aquarius’ left (i.e., to the celestial northeast). With Pegasus’ “home plate” as the bottom star, extend an imaginary line from third base to first base, and continue in the same direction by the same distance (about two fist diameters) to Aquarius’ highest and brightest star, Sadalmelik.

In a dark sky, up to 100 stars can be counted within Aquarius, but only a few are easily seen near city lights. Try to spot the four stars that extend a wide palm’s width from Sadelmalik eastward to the left. One of the four stars is a bit lower than the other three. At the eastern end of the foursome sits a modest star designated Eta Aquarii. The radiant of the springtime Eta Aquariid Meteor Shower is located close to that star.

Jumping 1.5 finger widths to the upper right of Eta brings us to a closely spaced double star (that splits in a telescope) named Sadaltager “Luck of the Merchant” that is only 91 light-years away from us. Two finger widths to the right of Sadaltager is the white star Sadachbia, which comes from the Arabic phrase sa’d al-akhbiya “Lucky Star of the Tents”. Then we hop higher to the right again (westward) to bright Sadalmelik, meaning “Lucky Star of the King”. Sadalmelik is a very mature, yellow supergiant star located about 520 light-years away from us. It’s a bit cooler than our Sun, but 60 times larger in diameter, making it much more luminous. Look for a fainter star named Omicron Aquarii shining about a thumb’s width to Sadalmelik’s lower right.

Ten degrees (a fist’s diameter) to the right of Sadalmelik, sits another of the constellation’s brighter stars, Sadalsuud “Luckiest of the Lucky”. Marking the water-bearer’s elbow, this is another yellow giant very similar to Sadalmelik and about as distant. Finally, Aquarius’ western hand is marked by a fainter, blue-white star named Albali “Good Fortune of the Swallower”, which sits a fist’s width to the right of Sadalsuud. A pair of fainter stars above and below Albali named Kappa and Nu Aquarii, respectively, may be his splayed fingers. Reddish Kappa also has the name Situla “water jar”.

The rest of the constellation, descending in two crooked lines from that chain of lucky stars, is fairly dim. About halfway along them, both lines take a jog to the left (east). The reddish, magnitude 3.7 star Hydor is named for the Greek word for “Water”, Hydro. Also known as Theta Aquarii, it sits where the eastern line jogs – a fat fist’s width below (or 8.6 degrees to the southeast of) Eta Aqr. Its western counterpart, below Sadalmelik, is yellowish Ancha “the Hip”. Aquarius’ western leg extends to the lower right from Ancha, passing Saturn and terminating at the white star Iota Aquarii.

Aim your binoculars to the lower left of Hydor and look for an up-down grouping of five medium-bright stars Psi, Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Psi, the lowest, is three stars spaced apart! The lower two are blue-white and the higher star Phi1 is orange. A generous palm’s width to their right (celestial west) you’ll see the star Tau Aquarii shining above Skat, the constellation’s third brightest star. The two descending lines end at the wide trio of stars named b1, b2, and b3 Aquarii (on the left, east) and the even wider split pair of c1 and c2 Aquarii on the right (west).

Aquarius contains only a few significant deep sky objects because it is situated away from the Milky Way, our galaxy’s central plane. The bright globular star cluster designated Messier 2, which can be spotted in binoculars or small telescopes, is only 4 finger widths above (or 5 degrees to the north of) Sadalsuud. It’s 37,000 light-years away!

A small planetary nebula named the Saturn Nebula (and also designated Caldwell 55) is located a similar span below Albali. At 650 light-years away, it’s among the closest such objects to us. The huge Helix Nebula (or Caldwell 63), another planetary, is located near the lower, southerly border of the constellation – about halfway between Saturn and Fomalhaut. The Helix is faint, but it’s almost the size of a full moon! Those two stellar corpses are visible in backyard telescopes on very dark nights. A second, dimmer globular cluster named Messier 72 sits below and between Albali and the Saturn Nebula.

For deep sky observers, Aquarius contains a handful of fine galaxies, including the NGC 7727 and nearby 7723, 7184, 7606, and 7721. Another globular star cluster named NGC 7492 is located between the two descending star chains some three finger widths to the left of Skat.

Saturn will shine with Aquarius’ bounds through next year and portions of 2025. Fittingly, the planet Neptune, named for the god of the seas, has been situated in Aquarius since 2011. Neptune won’t swim out of Aquarius permanently until 2024. At present, Neptune is located just on the Pisces side of its border with Aquarius, and less than a fist’s diameter to the left (east) of the Psi Aquarii trio of stars. On November 26, its westerly retrograde motion will carry Neptune back into Aquarius. I’ll post a sky chart for Aquarius and some photos of its splendors here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 3 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, telescope-building, planetary motions, and high school astronomy projects. Details are here.

If it’s sunny on Saturday morning, October 7 from 10 am to noon, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside the main doors of the Ontario Science Centre for Solar Observing. Come and see the Sun in detail through special equipment designed to view it safely. This is a free event (details here), but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!