Stargazing Time Stretches, a Super Full Harvest Moon, and Bright Planets Pose Morning and Night!

This image of the morning planet Venus showing its current crescent phase was captured through RGB and UV filters on a Celestron C11 telescope on September 22, 2023 by my friend Andrea Girones of Ottawa. Follow her as andrea_girones on Instagram and as @AndreaGirones on X/Twitter to see more of her fantastic images.

Hello, end-of-September Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 24th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The nights are lengthening in the Northern Hemisphere. The moon will shine brightly worldwide this week while it passes bright planets and waxes to a full Harvest Moon and the final supermoon of 2023. Saturn holds court in evening before Jupiter joins it later, and the inner planets shine before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Longer Nights

During this period around the September equinox, which happened yesterday (Saturday, September 23), the amount of daylight hours is diminishing at its maximum rate for the year in the Northern Hemisphere (and increasing at its maximum rate down under). At the latitude of Toronto, we’re losing 2 minutes and 58 seconds of daylight this week, but gaining the same amount of stargazing time!

That rate that we exchange of day for night will continue well into October, so you’ll see darkness falling about 20 minutes earlier with each passing week. Dust off the backyard telescope!

The Moon

After Friday’s first quarter moon phase, our natural nightlight will spend this week waxing toward a full moon on Friday, filling evening skies around the world with bright moonlight. That full moon will also be the last of the supermoon series for 2023.

Today (Sunday) the waxing gibbous moon will rise in late afternoon and then obscure the nearby faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) during evening. The curving pole-to-pole terminator boundary on the waxing gibbous moon will be falling across Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km-wide feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded “handle” on the western edge of that mare.

The “Golden Handle” effect is produced by way the rising sun lights up the peaks of the prominent curving Montes Jura mountain range surrounding Sinus Iridum on the north and west, while the floor of the bay at their feet remains unlit. Watch for a pair of promontories named Heraclides and Laplace that poke into Mare Imbrium to the south and north of the bay, respectively. Your telescope will show you that Sinus Iridum is almost craterless – so we know that it is geologically young. But it does host a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are nicely revealed at this lunar phase. Don’t fret if you miss seeing the Golden Handle. The effect returns every few months a few days before full moon.

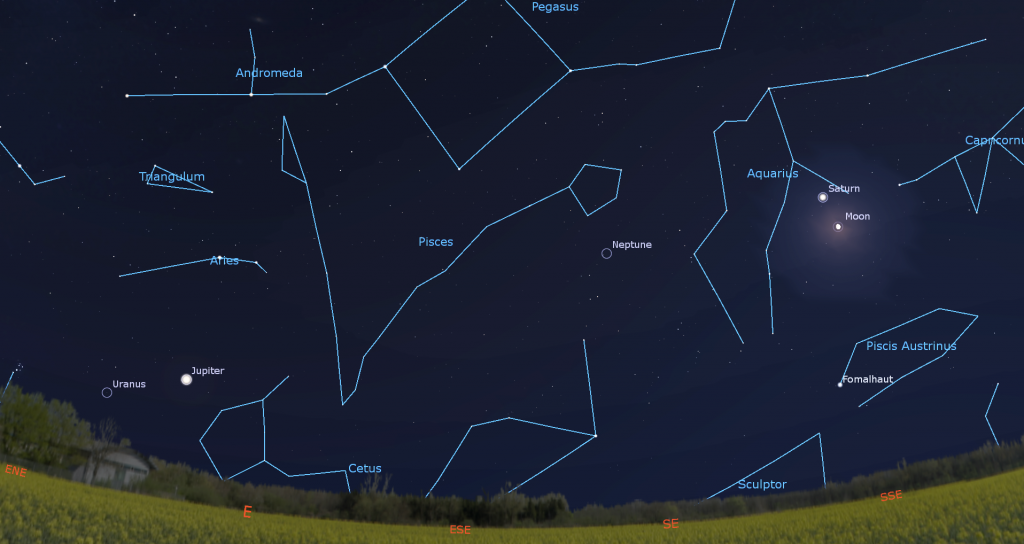

At sunset on Tuesday, the bright moon will rise over the southeastern rooftops a short time before sunset. Once the sky darkens more, the bright, creamy-yellow dot of Saturn will appear shining several finger widths to the moon’s upper left (or 4 degrees to its celestial north). The pair will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars as they cross the sky together all night long.

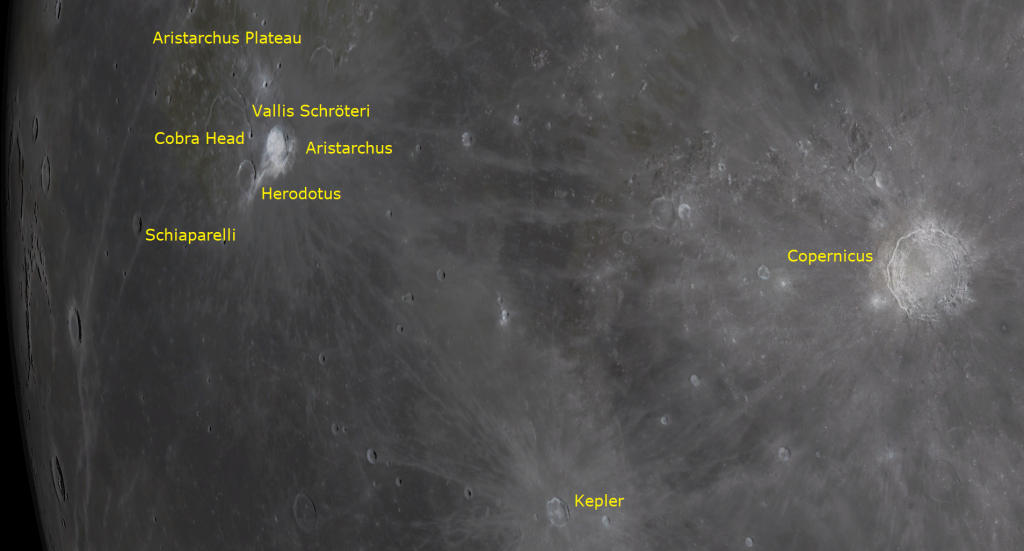

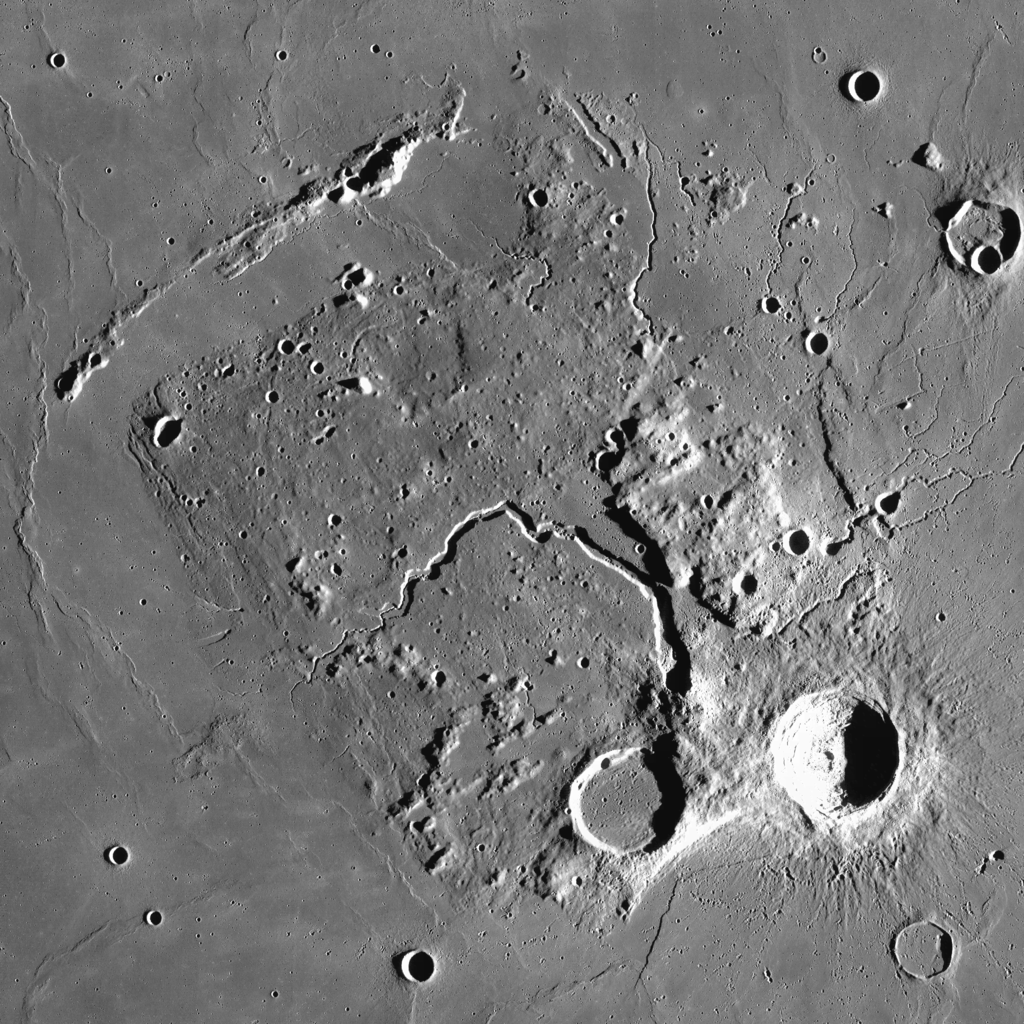

From Tuesday onwards, use your binoculars or telescope to look at the very bright spot of crater Aristarchus gleaming within a sea of dark grey rock near the moon’s left-hand (western) rim. It occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door crater Herodotus and slithers across the plateau. I never tire of looking at it! The large craters Copernicus and Kepler to Aristarchus’ lower right are surrounded by large, ragged ray systems – ejecta from their formation. The straight arcs of Tycho’s rays, which sits in the moon’s lower (southern) region, spread far across the moon.

From Wednesday to Friday, the moon will grow in illuminated phase and brightness, all but washing out the surrounding stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Pisces (the Fishes).

On Friday morning at 5:57 am EDT or 2:57 am PDT (or 09:57 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will officially reach its full phase, when it will be opposite to the sun in the sky. The September full moon, traditionally known as the Corn Moon and Barley Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Pisces (the Fishes). The indigenous Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Waatebagaa-giizis or Waabaagbagaa-giizis, the “Leaves Turning Moon” or “Leaves Falling Moon”. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the September full moon Nimitahamowipisim, the “Rutting Moon” – when the bull moose scrapes the velvet from his antlers as a sign that mating shall begin. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of Eastern North America call it Seskehko-wa, the “Time of Much Freshness Moon”.

Because this is the full moon occurring closest to the autumnal equinox in 2023, it is also the harvest moon. On the evenings around its full phase, the moon normally rises about 50 minutes later than the previous night. But around the equinox the shallow slope of the evening ecliptic (and the moon’s orbit) causes harvest moons to rise at almost the same time each night – only delayed by as little as 10 minutes, depending on your latitude. For Toronto latitudes, the delay is about 20 minutes.

The harvest moon phenomenon traditionally allowed farmers to work into the evening under bright moonlight – hence its name. It also means that if you arrive home from work, get the mail, or walk the dog at the same time every evening, you might notice the “full” moon for several days in a row. The effect is stronger the farther from the equator you live. The moon behaves the same way for Southern Hemisphere dwellers – but six months later, near their own autumnal equinox in March.

With no shadows anywhere, the light and dark areas on the full moon correspond to different rock types on the moon’s surface. The bright areas are the ancient, heavily-cratered lunar highlands composed of crystalline anorthosite rock, and the dark areas are younger maria, iron-rich basalts that have filled the oldest deep basins and which have fewer craters. The nights around full are also the best ones for seeing the bright ray systems surrounding the younger craters on the moon – material that was blasted out during the impact that formed the crater, and by the secondary impacts of the excavated chunks of rock.

A sure sign of autumn is that full moons rise majestically in the east well before bedtime, whereas the late sunsets of summer delay the full moon’s appearance until midnight. If you want to complete one of the lunar observing programs offered by the Royal Astronomical society of Canada or the Astronomical League of the USA, it’s better to tackle them in spring or autumn. During the summer months you’ll need to stay up until the wee hours to spend time exploring the moon. Winter moons are nice and high – but it’s so cold!!

The waning gibbous moon will end the week by venturing into Aries (the Ram). On Sunday night, October 1, the bright moon will shine close enough to the very bright planet Jupiter for them to share the view in binoculars. The duo will rise in the east at around 8 pm local time and then cross the sky all night long. By sunrise on Monday morning, the moon and Jupiter will be positioned high in the western sky. By then Jupiter will be positioned a palm’s width below the moon.

The Planets

Saturn will continue to draw our prime attention after dusk for the next month – until brighter Jupiter begins to steal its thunder. The ringed planet’s yellowish dot will appear above the southeastern horizon shortly after sunset, then shine all night long as it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope when it is higher in the sky – say after 8:30 pm local time. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be shining to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle well above it, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be found off to the planet’s upper left. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn all year long.

Saturn’s beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from close in on Saturn’s left (celestial northeast) tonight to the below the planet (celestial southeast) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

This summer the ice giant planet Neptune, currently 825 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Last Tuesday Neptune reached opposition for 2023. It is still shining with a slightly enhanced magnitude of 7.8. Since it is opposite the sun in the sky, Neptune will be visible all night long in backyard telescopes. Good binoculars can show it, too, if your sky is very dark – but this week’s bright moon will make it tough. Your best telescope views will come after 9 pm local time, when the blue planet has risen higher. Around opposition, Neptune’s apparent disk size will be 2.4 arc-seconds and its large moon Triton will be the most visible in telescopes.

Brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 21 times brighter than Saturn, will be clearing the eastern rooftops by 10 pm local time this week. Good telescope viewing time will start around 11 pm. That prime viewing window will commence half an hour earlier with each passing week. Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will be shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. Jupiter will spend the wee hours of the night following Saturn across the sky. It will definitely catch your eye while it gleams high in the southwestern sky before sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will gather on Jupiter’s right (or celestial west) on Saturday night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Monday, (with Io’s black shadow) on Thursday, and Saturday night, in the wee hours of Thursday and Saturday. It’ll also appear before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Wednesday morning, September 27, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 1:30 to 3:35 am EDT (or 05:30 to 07:35 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again, this time with the great red spot, on Thursday evening, September 28 from 8:00 pm to 10:05 pm EDT (or 00:00 to 02:05 GMT on Friday), best seen by viewers in western time zones. (These times may vary by a few minutes.)

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week Uranus will be located a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s lower left (or 7.9° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look, and when the moon isn’t too bright. I’ll get more specific in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

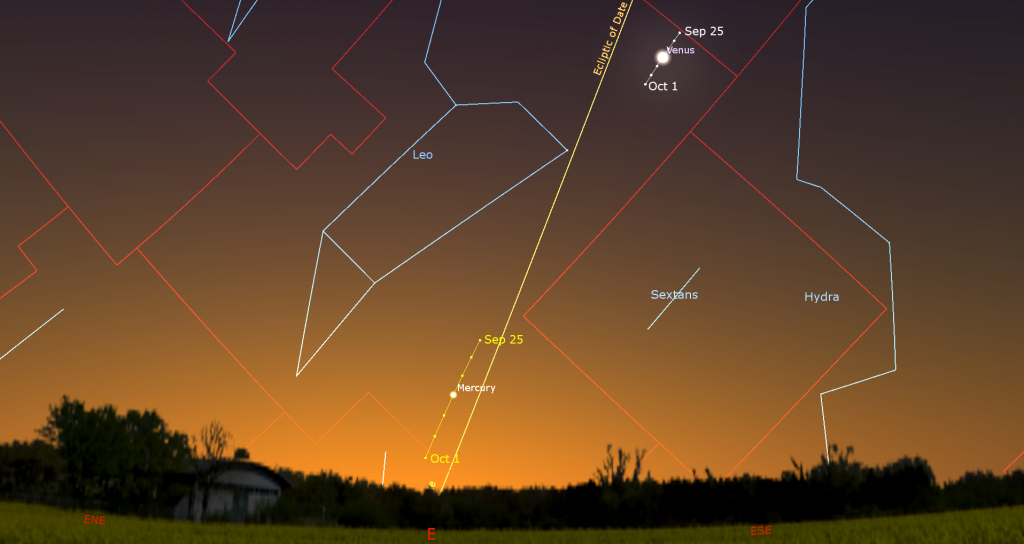

Early risers will see the brilliant beacon of Venus blazing in the eastern pre-dawn sky from now until January. It’ll be climbing farther from the sun with each passing day. Our sister planet will exhibit a large disk and a very slim waxing crescent phase in a telescope this week. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises. Venus will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) at about 3:30 am local time. The very bright star Sirius, which will be shining off to Venus’ right, will have risen around 2:45 am local time – joining the winter constellations Orion, Taurus, Gemini, and Auriga above it.

On Friday morning, the planet Mercury reached its maximum angle from the sun, and peak visibility, for its current morning apparition. You can still look for the innermost planet shining brightly to the lower left of Venus while it shifts lower in the eastern pre-dawn sky until almost 7 am in your local time zone. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 75%-illuminated, waxing phase.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On the first clear weeknight this week (Sept 25 to Sept 29) the public are invited to Binoculars Stargazing on the lawn at the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, and then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

On Friday, September 29 from 7:30 to 9:30 pm EDT, the in-person DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Quinton Weyrich, the outreach coordinator for the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada at the David Dunlap Observatory. He will speak on Taking Back the Night Sky: What We Can Do About Light Pollution.After the presentation, participants will tour the observatory and see a demonstration of the 74” telescope pointed to an interesting celestial object for the visitors to view (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy YouTube video about satellites is here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!