A Full Worm Moon Visits Virgo, Ceres Skims a Spiral Galaxy, the Gems of Gemini, and Springing Forward!

This beautiful image of Gemini’s Messier 35 and the smaller, but denser open star cluster NGC 2158 (below right of centre) was captured by “Mr. Eclipse” himself, Fred Espenak. Two more small open clusters shine at the far right – squint to see them! The image spans two thumb widths, or 2.5 angular degrees, left to right, making this area a great target for binoculars and a backyard telescopes at low power. Explore more of Fred’s work at http://astropixels.com/

Hello, March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 5th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where the old editions are archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

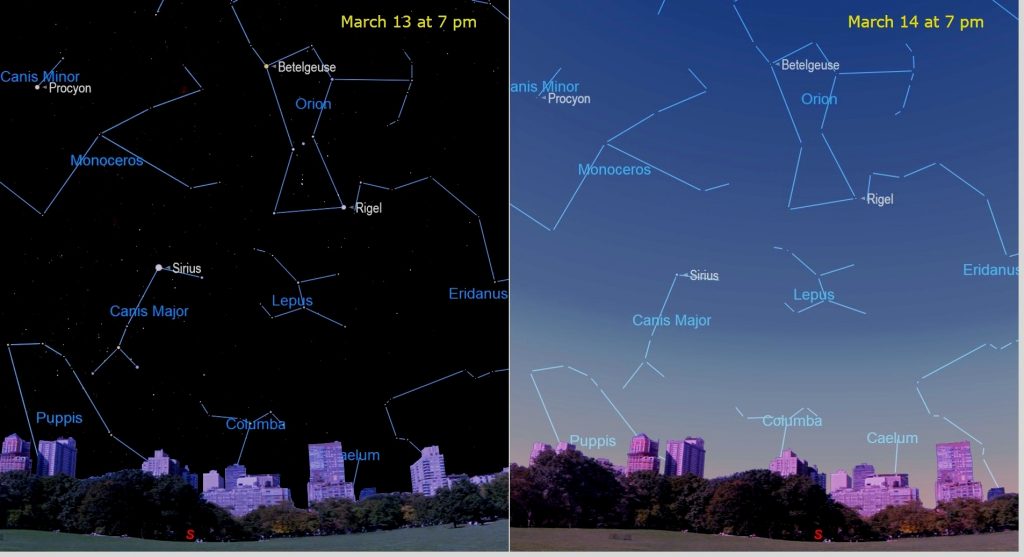

The bright moon will dominate the night sky worldwide this week as it reaches its full phase. After mid-week, its later rise time and waning illumination will allow for some evening stargazing, so I highlight the stars of Gemini. Brilliant Venus will separate from bright Jupiter in the western sky after sunset, leaving Mars shining on high in evening. And the clocks spring forward on the coming weekend. Read on for your Skylights!

Saving Daylight?

For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should be set forward by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday, March 12 – or before you go to sleep on Saturday night. In North America the “Spring Forward” will remain in effect until Daylight Saving Time reverts to Standard Time when we “Fall Back” on November 5, 2022.

For most of human history people woke with the sun and went to bed at dusk. At equatorial latitudes, where most people lived, hunted, and farmed, the number of hours of daylight through the year didn’t vary too much – so that approach worked well. But, as communities spread around the world and began to use standardize working hours – especially at latitudes farther from the equator where the days lengthened and shortened dramatically throughout the year – people were forced to use artificial light indoors when the sun wasn’t shining into windows.

Scientist/naturalist Benjamin Franklin, in a satire he published while living in Paris in 1784, proposed that Parisians get out of bed earlier to take advantage of the early sunrises in summer – and thereby save money on candles and oil in evening. For the same reason, during the 19th Century it became common for schools and businesses to adjust their operating hours with the seasons – but that practice wasn’t standardized.

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed what became Daylight Saving Time in 1895 – but he wanted the clocks to shift by 2 hours! The idea then spread to England where prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett, who was also an avid golfer, noted that more work (and golf) could be fit into the day if the clocks were advanced during the warm months. While the British parliament toyed with the proposal for years, it was Canada that led the way on Daylight Saving Time!

The first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908, was Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – followed soon after by Orillia, Ontario. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary adopted DST on April 30, 1916 as a way to conserve coal during World War I. Britain and most of its allies, plus many European neutrals soon followed. The USA adopted DST in 1918. Except for Canada, the UK, France, Ireland, and the United States, DST was abandoned after the war; but it was re-instated during World War II and then widely adopted as a result of the energy crisis of the 1970’s.

The inconvenience of twice-yearly clock changes has led to calls to abandon the practice. Some jurisdictions, including Ontario, Canada and the USA, are proposing to remain on DST year-round starting in November, 2023. I’d prefer to remain on Standard Time. For stargazers, advancing clocks by one hour, plus the fact that sunset occurs 1 minute later with each passing day near the March equinox, means that spring and summer star parties and dark-sky observing cannot begin until much later in the evening – usually after the bedtime of junior astronomers! Staying on DST will also mean that existing sundials will be permanently wrong because solar noon will always occur at 1 pm, and not at 12 pm.

The names and abbreviations for time zones change when DST is in effect. Eastern Standard Time (EST) becomes Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) – and so on. For those who deal with the timing of astronomical events, the difference between your local time and the international standard of Greenwich Mean Time (or GMT), and the astronomers’ Universal Time (UT), is reduced by one hour when DST is in effect.

One final thought. If your time zone is broad, covering many degrees of longitude, then, despite sharing the same time on the clock, the sunrise and sunset times can be radically different for locations on the eastern and western edges of the zone. The Eastern Time zone covers nearly two hours’ worth of longitude at the latitudes of Ontario and Quebec! If you want your summer sunsets to occur at the latest possible time, live in the western part of your time zone. If you prefer more daylight in the early morning, live as far to the east in your zone as possible. Trevor at Plateau Astro explained it very well on YouTube here.

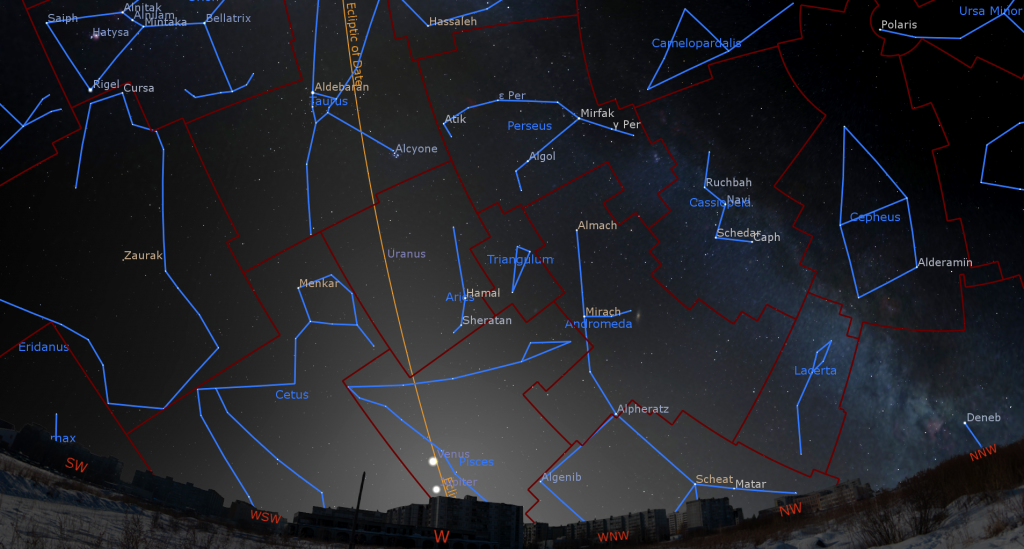

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light, which will appear during the two weeks that precede the new moon on Tuesday, March 21. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic above the planets Venus and Jupiter. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small dust particles that populate the plane of our solar system. Recent studies point to Mars as a major contributor to the dust! Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the winter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year.

The Moon

During the first part of this week, a bright moon will be shining during evening around the world. Since the moon will be rising about 65 minutes later each night, on the coming weekend we can squeeze in a couple of hours of stargazing before the bright moon rises.

Tonight (Sunday) the 98%-illuminated moon will shine near Leo the Lion’s brightest star, Regulus. Binoculars will show you a medium-bright star named Al Jabhah or Eta Leonis twinkling just above the moon. Observers in eastern and southern Africa can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) that star during the wee hours of Monday morning. The moon will spend Monday night in the sky between the lion’s feet stars.

The moon’s full phase will occur on Tuesday at 8:40 am EST, 5:40 am PST, or 12:40 Greenwich Mean Time. Full moons are, by definition, always opposite to the sun in the sky – so they rise in the east as the sun sets, and set in the west at sunrise. Since moon phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation, only observers in the Kolkata, India region will see this full moon rising at sunset. In the Americas, the moon will seem to be full on both Monday night and Tuesday night. But a magnified view of the moon on Monday will reveal that a thin strip along its left-hand (western) edge is in darkness. On Tuesday night, that dark strip will switch to the moon’s right-hand (eastern) edge because the moon has shifted from being west of the anti-solar spot in the sky to east of it.

Every culture around the world has developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon nowadays has one or more nick-names. The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call the March full moon Ziissbaakdoke-giizis “Sugar Moon” or Onaabani-giizis, the “Hard Crust on the Snow Moon”. For them it signifies a time to balance their lives and to celebrate the new year. The Cree of North America call it Mikisiwipisim, the “the Eagle Moon” – the month when the eagle returns. The Cherokee call it Anvyi, the “Windy Moon”, when the planting cycle begins anew. The March full moon always shines in or near the stars of Leo (the Lion) or Virgo (the Maiden). It is also known as the Worm Moon, Crow Moon, Sap Moon or Lenten Moon. This full moon will also launch Holi, the Hindu festival of colours, which will be celebrated on Tuesday night and Wednesday.

When fully illuminated, no shadows are cast by terrain – so the moon’s geology is enhanced, especially the contrast between the bright and ancient heavily cratered highlands and the younger, smoother, dark maria. Grab your binoculars and look for the many ray systems sprayed across the full moon’s face. The rays are straight lines composed of material that has been thrown radially outwards when objects that slammed into the moon created its more recent craters. The rays are particularly apparent when the moon is lit face-on, as it is around the full phase. Viewed in a telescope, major rays can be shown to be chains of small secondary impact craters excavated by the falling chunks of excavated rock (or ejecta), and by scattered debris itself. Impacts on the light-coloured lunar highland rocks tended to spread white rays over the surrounding darker mare regions – but sometimes the inverse happens.

Some ray systems are enormous – spanning half the moon’s disk! The ray system of the crater Tycho is a fine example. Tycho is the very bright crater located in the south central part of the moon. Its rays are largely missing on the left-hand (lunar western) side, suggesting that its impactor, an asteroid 8 to 10 km in diameter, arrived from the west at an angle less than 45° above the lunar surface, throwing the ejecta in front of it, mainly to the east. In a telescope, you can see that Tycho is encircled by an asymmetrical dark blanket of rubble that is about as wide as the crater’s 85 km diameter. The dark colour is probably basaltic rock excavated from deep below the crust. Tycho and its rays are bright because it is a relatively young crater – only about 109 million years old. The dinosaurs were walking the Earth when the violent event happened! It’s too bad they couldn’t tell us what they saw!

The small crater Proclus is located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). Proclus’ bright rays only extend toward the right-hand side of the crater, mainly onto Crisium. Look for symmetrical, but ragged ray systems around the big craters Copernicus and Kepler in Oceanus Procellarum, which covers the moon’s left-hand (western) side.

The bright moon will wane and rise later each night. It will spend Tuesday to Friday crossing the lengthy constellation of Virgo (the Maiden), and then it will pass in to Libra (the Scales) next Sunday. After about mid-week, early risers will be able to see the moon shining low in the south and western sky after the sun rises.

The Planets

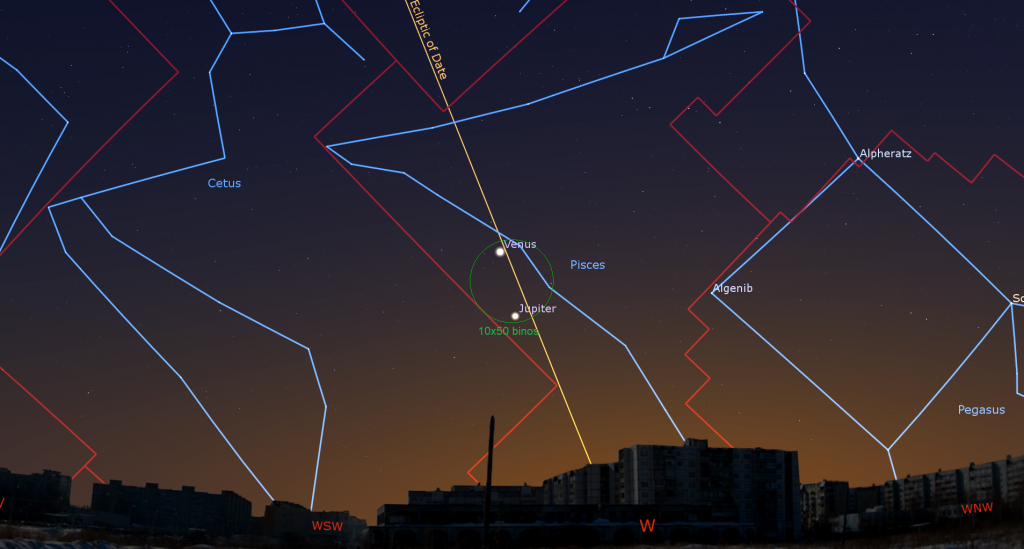

After their shared “kiss” last Wednesday, the very bright planets Venus and Jupiter will continue to dazzle us in the western sky after sunset this week. Every night Jupiter is being carried downward (sunward) along with the background stars while Venus’ eastward orbital motion is moving it upward in the opposite direction. Tonight (Sunday) magnitude -2.1 Jupiter will shine less than a palm’s width below (or celestial west of) five times brighter Venus. They’ll be cosy enough to share the view in your binoculars until about mid-week. Next Sunday night, they’ll have doubled their separation.

The daily descent of Jupiter is also ending our clear views of that planet. Since you’ll be able to see Venus pop out of the bright twilit sky first, you can use it to locate Jupiter and view it while it’s still high enough in the sky for clarity. You aren’t likely to see the Great Red Spot or any shadow transits, though. Binoculars and a backyard telescope will still show Jupiter’s Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. Jupiter will set around 8:15 pm in your local time zone.

Venus will put on a better show each night due to its increasing distance from the sun. It will be with us after sunset until well into summer. For now the planet will follow Jupiter down around 9 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will display a slowly waning, 84%-illuminated disk. To see its shape most clearly in a telescope, look at Venus as soon as you can put it into your optics, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Take care to avoid aiming near the sun.

Uranus will set next – at about 11:15 pm local time this week. Its magnitude 5.8 dot will sit close to the ecliptic, nearly halfway from Venus to Mars. You can also search a generous fist’s width to the left (or 13° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). The medium-bright stars Pi Arietis and Sigma Arietis, which are similar in brightness to Uranus, will flank the blue-green planet in the same binoculars field of view. The best time for telescope-viewing of Uranus is right after dusk, when the planet will be located halfway up the west-southwestern sky. It will become too low for good views after by 9 pm.

Mars continues to be easy to see starting after dusk each night – but it continues to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from the red planet. On a night with steady air (i.e., the stars aren’t twinkling too much) you can try using a high magnification eyepiece to see the largest dark markings on its ochre 7.8 arc-seconds-wide disk. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

Mars will be starting to descend from its highest point (and its absolute best telescope viewing time) right after dusk. Look for its reddish dot shining between the horns of Taurus (the Bull) and 1.4 fist widths to the upper left (or celestial east-northeast) of the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of the beast. The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling off to Mars’ right (celestial west). Each night you can watch Mars moving eastward, farther from Aldebaran and the Pleiades and towards the foot stars of Gemini (the Twins). Mars will descend the western sky through the night and set during the wee hours.

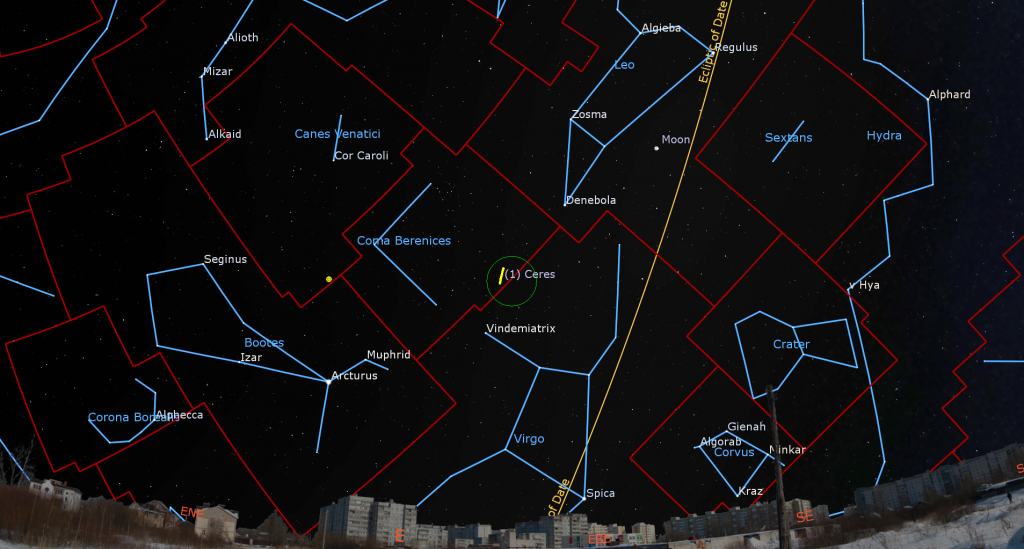

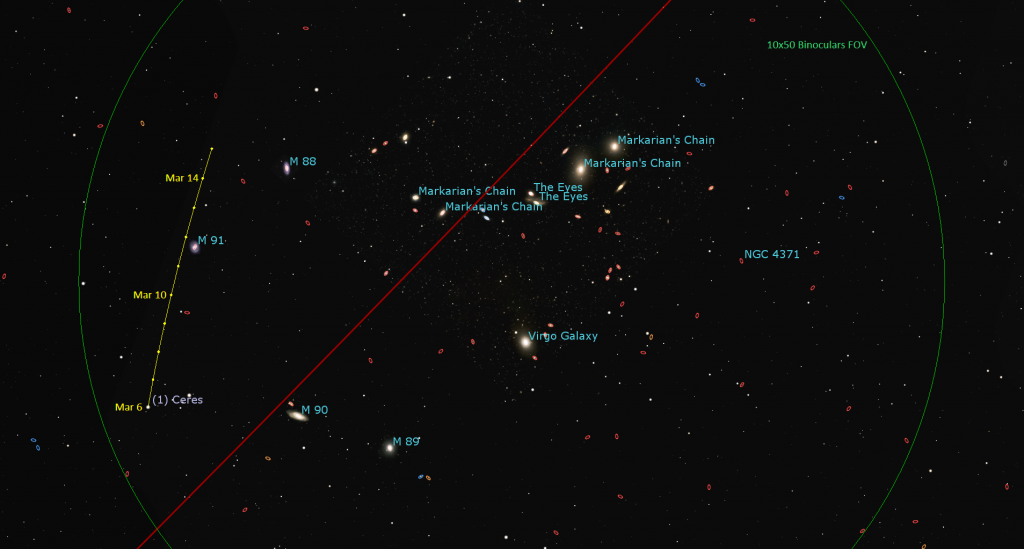

During March, the largest object in the main asteroid belt, named (1) Ceres, will perform a westerly retrograde loop that carries it through the northern edge of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies. That region of the sky is located about midway between the bright stars Denebola in Leo (the Lion) and Vindemiatrix in Virgo (the Maiden). It contains thousands of galaxies and quite a few larger ones that are visible in backyard telescopes under a dark sky.

On Saturday night, the 7th magnitude minor planet Ceres will pass a tiny distance to the left (or only 5 arc-minutes to the celestial north) of the prominent spiral galaxy named Messier 91. They’ll be close enough to view together in a backyard telescope for a week starting on Tuesday. Unfortunately the bright moon will be shining nearby on Tuesday, so look a few nights later if you can’t see the faint galaxy on Tuesday. Don’t forget to hunt around a little for more of the cluster members! They’ll look like oval fuzzy patches.

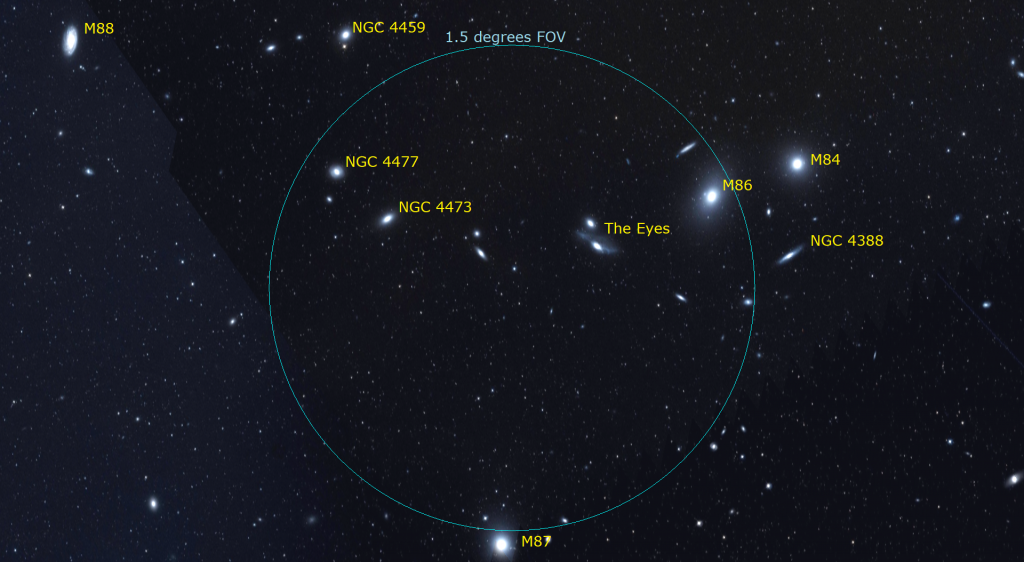

Ceres will clear the eastern rooftops by about 8 pm local time – but the pretty galaxy’s fainter form will be best viewed in late evening, when the duo will be halfway up the southern sky. Ceres will pass 0.5 degrees north of another galaxy named Messier 88 on March 14-15. By then the moon will not interfere. During the week, telescope-owners can check out Markarian’s Chain of galaxies, which arcs to the right (or celestial southwest) of both Messier 91 and 88. (I published an article about viewing Markarian’s Chain in the current issue of SkyNews Magazine, which is available at Canadian news stands.)

The Gems of Gemini

The moonless evenings toward the end of this week will be ideal for enjoying the best of the winter Milky Way – especially if you can escape the lights of the city. Even if you are limited to driveway stargazing, there is plenty to discover. I toured you through Orion (the hunter) here. Let’s highlight some gems to see in Gemini (The Twins) – with your unaided eyes, or in binoculars and telescopes.

In mid-evening during March, the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins) is positioned high in the southern sky, to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of Orion (the Hunter). They are bordered on the east by Cancer (the Crab) and on the west by Taurus (the Bull). The bright stars of Auriga (the Charioteer) shine to Gemini’s upper right (northwest). The faint constellation of Lynx borders Gemini to the northeast. Canis Minor (the Little Dog) and Monoceros (the Unicorn) shine to the south. Although the constellation is 24 degrees north of the celestial equator, it is visible from everywhere on Earth except Antarctica.

Gemini is one of the original 48 constellations that the ancient Roman astronomer Claudius Ptolemy recorded in his Almagest, which was published around 150 CE. The ancient Babylonians associated the twins with Plague and Pestilence, aspects of their god of the Underworld. In Greek mythology, the twins were half-siblings. Pollux was born when Zeus seduced Leda, the wife of the king of Sparta. She also bore the king a mortal son, Castor. The brothers became crew members on the Argo, which was captained by Jason in search of the Golden Fleece. When Castor died, Pollux asked Zeus to restore his life. Instead, he united the brothers in the stars. For the Romans, the stars were Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome.

The Inuit used the bright star Capella in Auriga (the charioteer) plus Castor and Pollux of Gemini to form the Collarbones or Quturjuuk. For the Dakota / Lakota of North America, Castor and Pollux marked part of the Sacred Hoop “Can fleska wakan”, an asterism Europeans call the Winter Hexagon. For them the rest of Gemini’s stars formed Mato Tipila, the Bear’s Lodge. Interestingly, that is also their traditional name for Devil’s Tower, the pillar of igneous rock in Wyoming made famous by the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The Mayas viewed Gemini’s rectangular shape as a celestial Ball-court. Astro-archaeologists have discovered that some of those structures featured alignments to the sun on the solstices and equinoxes.

In the sky Gemini is dominated by the bright stars Castor and Pollux, which mark the heads of the twins. At first glance, those two stars look alike – but they are somewhat different in brightness and colour – as implied by their diverse paternity. Castor is a white, magnitude 1.9 star of spectral class A1. A backyard telescope will resolve it into a pretty double star with a separation of 5.2 arc-seconds – but Castor is composed of six stars located 51 light-years from our sun. Castor is always on the right-hand (western) side of the constellation when the twins are standing upright.

Pollux, the star marking the head of the more easterly (left-hand) twin shines at magnitude 1.15, making it slightly brighter than Castor. Pollux is a yellow giant star located 34 light-years from the sun. It is known to be orbited by a large, hot-Jupiter-type exoplanet proposed in 1993 and confirmed in 2006 by astronomer Artie P. Hatzes. Formally known as Pollux b, in 2014 the planet was assigned the name Thestias, after the maternal grandfather of Pollux in Greek mythology. The colour differences in the twin’s stars reflect their different photospheric temperatures. A star’s photosphere is its apparent surface, the radius where it becomes opaque to visible light. The A-class star Castor “burns” hotter than K-class Pollux. The radiant point for the annual Geminids meteor shower, which peaks around December 13, is near Castor.

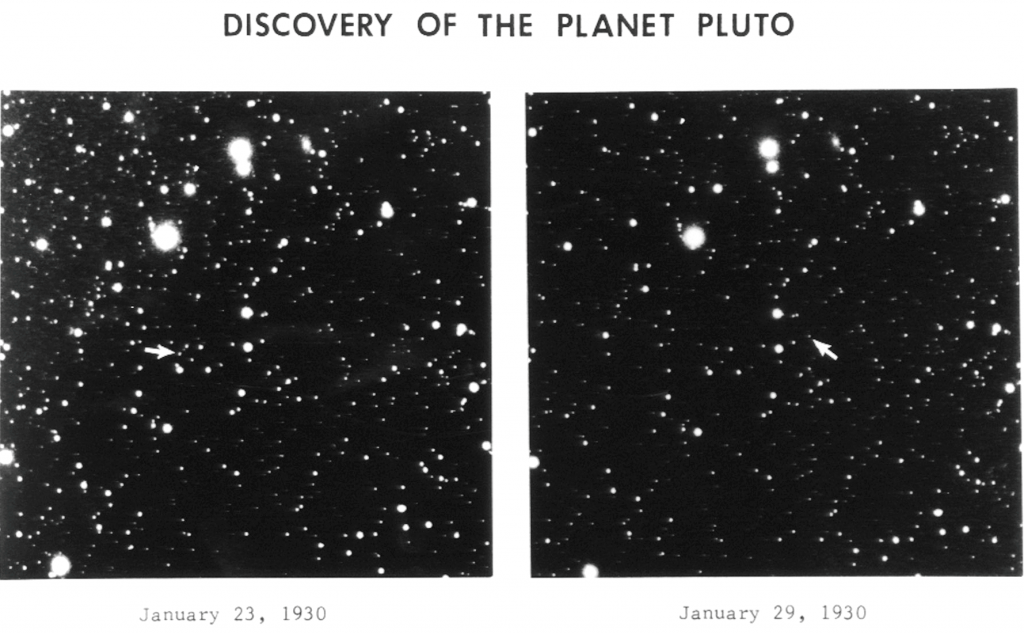

The very bright, orange star Betelgeuse in Orion (the Hunter) is located about three fist diameters to the lower right (or 33° to the celestial southwest) of Castor and Pollux. Two medium-bright stars sit about a fist’s width towards Betelgeuse from Castor and Pollux. On the east, the magnitude 3.5 star named Wasat, from the Arabic word for “middle”, marks Pollux’ waist. It’s also designated Delta Geminorum (δ Gem). The ecliptic passes only 0.15° north of Wasat, so it can be occulted by the moon and planets from time to time. When Clyde Tombaugh of Lowell Observatory compared photographs the sky he took just east of Wasat on January 23 and 29, 1930, he noted an object that had moved. He had discovered Pluto!

The yellowish, magnitude 3.1 star named Mebsuta or Epsilon Geminorum (ε Gem) defines Castor’s waist. Mebsuta used to be part of another Arabic star pattern. Its traditional names Mebsuta, Melboula, and Melucta all come from an Arabic phrase referring to the outstretched paw of a lion. The yellowish, medium-bright star below and between Wasat and Mebsuta, named Mekbuda or Zeta Geminorum (ζ Gem), was another part of that lion’s folded paw. Mekbuda marks Pollux’ western knee. A backyard telescope will split Mekbuda into a pair of stars. Pollux’ eastern knee is a slightly brighter, whiter star named Lambda Geminorum (λ Gem).

Have a look for the crooked line of five stars that forms the hands and arms of the twins. Running from left to right (or celestial southeast to northwest) below Castor and Pollux, they are Kappa, Upsilon, Iota, Tau, and Theta Geminorum. Spanning about 1.4 fist diameters, they are almost bright enough to see from the suburbs on moonless nights. Aim your binoculars above Iota and look for the nearby bright little duo of stars 64 and 65 Geminorum.

Another row of widely-spaced stars that occupy the sky below (south of) Wasat and Mebsuta represent the feet of Gemini. At lower left (southeast) is warm white Alzirr or Xi Geminorum (ξ Gem) from the Arabic exression al-zirr “the button”. Alzirr is surrounded by several nearby, fainter stars. Several finger widths to its upper right (celestial west) is the white star Alhena or Gamma Geminorum (γ Gem). Alhena is derived from the Arabic phrase al han’ah, “the brand (on the neck of the camel)”. Its alternate name Almeisan is from Al Maisan, “the shining one”. Those two stars, which mark Pollux’ eastern and western feet, are located 58 and 110 light-years from our sun, respectively.

Several finger widths to Alhena’s upper right sits dimmer Nucatai or Nu Geminorum (v Gem), an easy-to-split double star located 544 light-years away. The main star in that pair is a blue giant. Castor’s westerly foot is made from two reddish, M-class stars named Tejat Posterior and Tejat Prior – plus a fainter “toe” star to their right (west) designated 1 Geminorum. Tejat Prior is often called or Propus (η Gem), from the Greek term for “forward foot”, since it precedes the others across the sky. The gentle arc formed by the stars of both twins’ feet was also called “the Camel’s Hump” by ancient Arab astronomers.

Mekbuda is also a Cepheid variable star that varies in brightness every 10.2 days as the star swells and cools and then contracts and brightens. At its dimmest, it shines at about the same brightness as magnitude 4.1 Nu Geminorum. When brightest it shines almost as bright as Wasat.

Both twins of Gemini are cooling their toes in the Milky Way, so the southwestern realm of that constellation includes many deep sky gems. The sky to the upper right (northwest) of Propus hosts Messier 35, a beautiful, bright open star cluster composed of more than 100 brighter stars. Some star maps label it as the Shoe-Buckle Cluster. You can see Messier 35 with your unaided eyes if the sky is dark, and in binoculars or small telescopes in more marginal conditions. A fainter and more distant cluster designated NGC 2158 sits only a pinky finger’s width below (southwest of) Messier 35. A faint, but large nebula called the Jellyfish Nebula (or IC 443) is located between Tejat Posterior and Propus.

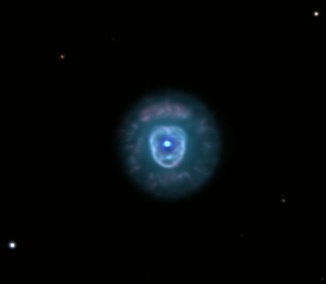

The Parka Nebula (also designated NGC 2392) is a spectacular planetary nebula visible in backyard telescopes – but use high magnification because it’s tiny, like a distant planet! This corpse of a former sun-sized star actually resembles a face surrounded by a fur-lined parka. The magnitude 9.1 object sits a little more than 2 finger widths to the left (southeast) of Wasat. Another lovely open star cluster designated NGC 2420, and sometimes called the Twinkling Comet Cluster, is located two finger widths to the left (or 2.25° to the celestial northeast) of the Parka. The easiest way to find it is to look 4 finger widths to the lower left (celestial east) of Wasat.

A brighter nebula called the Monkey Head (NGC 2174) is located two finger widths below (or 2° to the celestial south-southwest of) Propus, putting it within the boundaries of Orion. Several more bright clusters and nebulas are located a few finger widths to the lower right of Alzirr, in northern Monoceros (the Unicorn).

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Stargazers located near Oshawa, Ontario can join RASC members for a free public star party on Tuesday, March 7 from 6 to 7:30 pm at the Courtice Community Complex, 2950 Courtice Rd, Courtice, Ontario. If bad weather prevents stargazing, the event may be postponed to Wednesday, March 8 or Thursday, March 9. Check rascto.ca or the Clarington Public Library’s events page for a Go/No-Go decision based on the weather. More information is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, March 14 at 3:30 pm EST. Since it’s March Break, we’ll tour the early spring sky and showcase sights to see with unaided eyes, through binoculars, and in telescopes of any size. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!