A Mostly Morning Moon, Venus nears Neptune as Mercury Moves up, and Touring Awesome Orion!

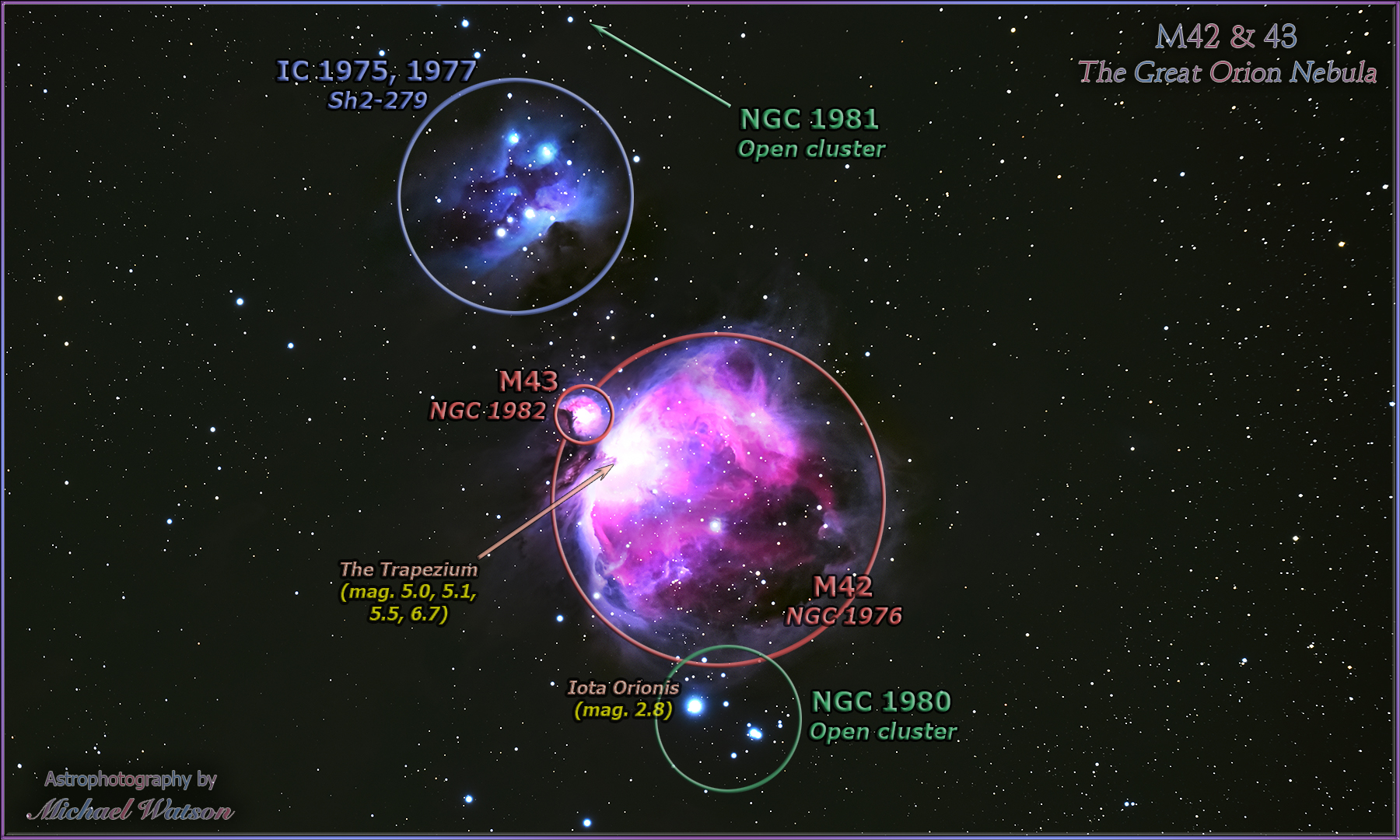

This spectacular astrophotograph of Orion’s Sword by Michael Watson of Toronto has been annotated to highlight the many and varied deep sky objects in this part of the sky. The colourful Messier 42 nebula is glowing by the light of young stars formed within it. The area shown here covers about 2 finger widths of the sky. Michael’s gallery of other beautiful images is here.

Hello, late January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 19th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where all the old editions will be archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The moon will be missing from nighttime skies the world over this week – so skies will be perfect for hunting the comet in Perseus as it flies past some beautiful clusters and nebulas. We take a look at Orion’s treats, too. After sunset, lovely Venus will shine brightly in the western sky, with Mercury joining the fun – and Mars will slide away from its rival in the pre-dawn east. Here are your Skylights!

The Moon and Planets

The moon starts this week in the eastern pre-dawn sky, heading towards its monthly meeting with the sun. In the southeastern sky during the hours preceding dawn on Monday, the waning crescent moon will be positioned less than four finger widths above (or 4 degrees to the celestial northwest of) Mars. The duo will fit nicely together into the field of view of binoculars.

On Tuesday morning, the very slim, old crescent moon will be lower in the sky, but it will remain a pretty sight in the southeast before sunrise. For Wednesday, look for the bright speck of Jupiter sitting a generous palm’s width to the lower left of the moon, which will be sitting very low indeed. Approximately fifteen hours later, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will produce an occultation of Jupiter for observers in Madagascar, the Kerguelen Islands, southern and eastern Australia, New Zealand, southern and eastern Melanesia, and southwestern Polynesia!

The moon will officially reach its new moon phase, when it will be completely hidden from view beside the sun, on Friday at 4:42 pm EST (or 21:42 GMT). This new moon will also kick off the Chinese New Year and the Spring Festival 春节, or Chūn Jié, which runs until the full moon in two weeks. Happy Year of the Rat! No one on Earth will see the moon easily again until Saturday, when it will appear as young crescent sitting very low in the southwestern sky just after sunset. Sharp eyes might also spot Mercury lurking only two finger widths to the right of the moon on Saturday. Finally, on Sunday night, the moon will be higher in the sky, and will make a pretty sight sitting below Venus.

Speaking of Venus, our sister planet Venus will continue its lengthy winter appearance this week – shining as an extremely bright point of light in the southwestern sky among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Venus will set at about 8:30 pm local time, in a dark sky. Viewing Venus in your telescope now and during the upcoming weeks will reveal that its shape is less than fully round because the sun is starting to shine on it from the side. Venus will continue to wane in phase as it swings wider from the sun between now and the end of April. Use your telescope on Venus while the planet is higher in the sky, and after the sun has completely set – starting at about 6 pm local time. That way, you’ll reduce the amount of distorting air you will be looking at Venus through.

Mercury is in the early days of a fantastic evening appearance for Northern Hemisphere observers. It will reach peak visibility on February 10 – but for now, you can hunt for it very low over the south-southwestern horizon right after sunset. It will climb a little higher every day. By the coming weekend, the optimal viewing time will be just before 6 pm local time.

Only the harder-to-see ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune are available for evening viewing once Venus and Mercury drop toward the horizon. Despite their relatively dim visual brightness and small disk sizes, the delightful colours of those two remote planets make them worthy of a look in backyard telescopes – especially while the moon is away.

This week, distant and dim, blue Neptune will become too difficult to see well in the hour before it sets at about 10:15 pm local time. You should try to observe Neptune as soon as the sky darkens, when the planet is higher – and sitting a bit less than a third of the way up the southwestern sky. Slow-moving Neptune has been situated among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) for months, and is positioned less than a finger’s width to the lower right (or 1 degree to the celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. I posted a detailed finder chart here.

Both blue Neptune and golden-coloured star Phi Aqr will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at low magnification. Find Phi Aqr first and then locate nearby Neptune. Remember that binoculars will display the true relative positions of the objects, but a telescope will flip and/or mirror-image the view. (To find out what your telescope does to an image, see how it changes the view of the moon, and make a note of the result.) Venus is going to “kiss” Neptune next week. That meeting will let you find and see Neptune easily. Stay tuned!

Blue-green Uranus is observable from dusk until about midnight (it sets at 1 am local time). It is located a generous palm’s width above (or 7° to the celestial east of) the modest stars that form the V-shaped constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Uranus is actually located within the boundary of Aries (the Ram) – positioned below (or to the celestial south of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Sheratan and Hamal. The planet is also a fist’s diameter to the upper right of the ring of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Sea-Monster).

Shining at magnitude 5.7, Uranus is bright enough to see under dark sky conditions with unaided eyes and with binoculars – or through small telescopes under less-dark conditions. To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here. If you view Uranus after about 6:15 pm local time, it will be highest in the southern sky – and you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

Mars continues its show in the southeastern pre-dawn sky. It will remain there for several months to come. The red-tinted planet will rise at about 4:40 am local time and remain visible until dawn. The relative positions and combined orbital motions of Earth and Mars are causing Mars to appear in roughly the same place in the sky at the same time every morning. However, the planet is actually moving rapidly eastward in front of the distant background stars because they rise four minutes earlier every morning – while Mars does not.

This week, Mars will move to the lower left (celestial east) of its nearby stellar rival, the bright, ruddy-tinted star Antares, which will appear a palm’s width to the lower right of the planet. In a few months, Mars will start to appear larger and brighter as it gears up to next autumn’s opposition.

Awesome Orion

Annually in mid-January, the southeastern evening sky is dominated by the eye-catching constellation of Orion (the Hunter) and his famous three-starred belt. Orion contains some of the sky’s most spectacular sights – whether using your unaided eyes, binoculars, or telescopes of any size! Orion’s spectacular stars and the bright nebulas in his sword and belt make cold winter nights much more rewarding for skywatchers. So let’s bundle up against the winter chill and take a tour of the hunter.

Orion has traditionally been depicted as kneeling, or standing. His eastern arm is raised and bears a club. His western arm is outstretched and holds a lion’s pelt, or a shield. Orion is a medium-sized constellation measuring about 30° (three outstretched fist widths) from his upraised club to his toes/knees, and 20° from his eastern elbow to the lion’s pelt. In early evening, after 7 pm local time, Orion is low in the southeast, his head tilted a little to the east (that’s to the left for observers in the Northern Hemisphere). As the evening wears on, Orion climbs higher and rotates fully upright, culminating in the south at around 10 pm. Then he leans the other way as he sinks into the west to set about 4 am local time.

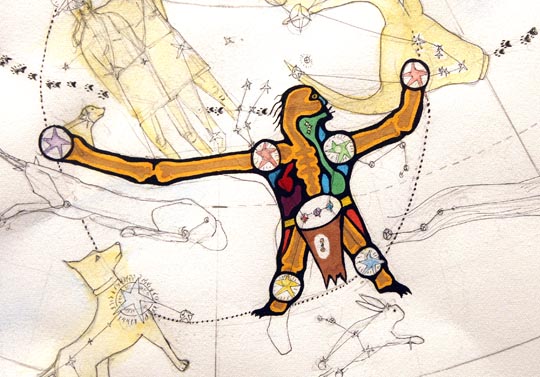

The indigenous groups of North America associate Orion’s stars with the constellation of Biboonikeonini, the Winter-Maker. They lengthen his arms so that his hands hold the bright star Procyon on the east and Aldebaran on the west.

Not surprisingly, many cultures have also assigned meanings to the distinctive row of three equally spaced stars that mark Orion’s Belt. Scandinavian countries have seen a distaff, a scythe, and a sword. Predominantly Catholic countries referred to it as The Three Mary’s (as featured in the New Testament). In the Middle East, it has been identified as The Three Kings or Magi. In China, it is known as The Weighing Beam and the Three Stars. In fact, the top portion of the Chinese character, 參 (shēn) has three identical symbols representing the three stars. The Lakota people called it the Bison’s spine – with surrounding stars and nearby constellations forming the rest of a great bison in their winter sky. When viewed from the Southern Hemisphere, Orion is upside-down – and his belt and sword combine to form a frying pan!

From left to right (or east to west in the Northern Hemisphere), the three belt stars are named Alnitak, Mintaka, and Alnilam. In a telescope, Alnitak (“the Girdle”) is revealed to be a double star. The larger, main star of Alnitak’s pair is a blue supergiant star located about 820 light-years from us. It emits tremendous amounts of ultraviolet light – its surface temperature is a scorching 31,000 Kelvin (which is pretty much the same as 31,000 Celsius at those extremes)! For comparison, our gentle yellow sun is a mere 6,200 K! Astrophotographers love the area around Alnitak because it sits just to the right of the Milky Way, and is loaded with gorgeous gas clouds and nebulae.

The belt’s middle star, Alnilam (“String of Pearls”), is another large and very hot, blue-white star. It’s located about 1.5 times farther away from us than the two other belt stars. Aging rapidly and nearing the end of its hydrogen supply, Alnilam is expected to become a red supergiant – the pre-cursor to a supernova, at any time. Since it’s more than 1,300 light years away – that explosion may already have happened!

The third and westernmost star, called Mintaka (“Belt”), is also a double star when viewed in a telescope. In fact, there are at least four stars making up what we see as Mintaka. The brightest one has a partner that orbits it every 5.73 days in an eclipsing binary configuration that makes the star vary in brightness. The dominant stars in Mintaka’s family gathering are also hot, blue giants. The group is located about 900 light years away. If you look carefully, Mintaka is actually somewhat dimmer than Alnitak and Alnilam. Look for a large upright letter “S” composed of dim stars in the sky between Alnilam and Mintaka.

The bright, orange-coloured star named Betelgeuse (usually pronounced “BEE-tel-jews”) marks Orion’s eastern armpit or shoulder. That funny-sounding name comes from the Arabic expressions “Ibṭ al-Jauzā”, meaning “the armpit of Jauza”, or “Yad al-Jauzā”, “the hand of Jauza”. Jauza was the Arabic name for the person depicted in Orion constellation. In Chinese, Betelgeuse is called 参宿四 Sānsù Sì, “The Fourth Star of the constellation of Three Stars”.

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant star located about 500 light-years away. Placed in our Solar System, all the inner planets out to Mars would be inside the star! Despite an age much less than our Sun (it is of a type that matures dramatically faster), astronomers think it is approaching the end of its life and is massive enough to explode as a Type II Supernova.

Normally, Betelgeuse ranks as the ninth brightest star in all the night sky. But in the past weeks it has dimmed dramatically. While Betelgeuse has been known to dim and brighten throughout the many years that astronomers have been recording its brightness, this recent dimming is far below what’s typical. We might be seeing a signal that the end is near. Or it might just return to normal. We can’t say. Since it takes about 500 years for light to reach us from Betelgeuse, it could already have exploded! If it does go supernova, we’re in no danger. We’ll just be treated to a spectacularly bright point of light for days or weeks.

To the lower right of Orion’s belt sits the hot blue star Rigel. It is (usually) approximately the same visual brightness as Betelgeuse, despite being located much farther away from us – meaning that it emits considerably more light. Rigel, too, is a supergiant star burning with a surface temperature of 11,000 K! In a good telescope, a small companion star can be spotted very close to Rigel. In Arabic, Rigel means “the Foot of the Great One”. In China, Rigel is known as 参宿七 (Sānsù Qī, “The Seventh of the Three Stars”).

Orion’s western shoulder is marked by the bright star Bellatrix, which translates as “Amazon Star”, after the warrior women of legend. Bellatrix is about 240 light years away from us, and burns at a blistering hot 21,500 K – among the hottest stars known. It, too, is well along in its life cycle, and is expected to soon enter its next phase of evolution – and turn an orange colour.

Above and between Orion’s shoulders is an open cluster of stars, 1305 light-years distant, that form his head. The brightest star is named Meissa (“the Shining One”). Use binoculars or a telescope to enjoy them better, and see how many stars you can count.

Completing our circuit of Orion’s main body, the western foot or knee of Orion is the mis-named star Saiph or “Sword of the Giant”. Another hot, blue white star with a surface temperature of 26,500 K, Saiph is also nearing the transition to creaky, old red supergiant.

The lion’s pelt, or shield that Orion is holding is composed of a crooked line of about nine stars that run up-down off to Orion’s western side. The brightest star, in the middle of the string, is named Tabit (“the Endurer”). On the opposite side of the constellation, Orion’s upraised club dips into the Milky Way. As you move up the club, the pairs of stars that define it sit wider apart. Binoculars will nicely reveal the rich star fields there.

We can use Orion’s stars as pointers to other ones. Extending the belt stars to the west leads to the bright orange-ish star Aldebaran in Taurus (the Bull). Heading two fist diameters in the opposite direction leads you to the Dog-star Sirius, the brightest star in the entire night sky. A line drawn from Bellatrix to Betelgeuse points to Sirius’ bright puppy, Procyon. And the line from Rigel up through Betelgeuse leads to the two matched stars Castor and Pollux, the heads of Gemini (the Twins).

Orion’s spectacular sword is one of winter’s true astronomical treats. The sword is located a few finger widths below Orion’s belt. Unaided eyes can generally detect three patches of light in Orion’s sword, but binoculars or a telescope will reveal that the middle object is not a single star at all, but a bright knot of glowing gas and stars known as The Orion Nebula (or the Great Nebula in Orion, Messier 42, and M42).

The Orion Nebula is one of the brightest nebulae in the entire night sky and, at 1,400 light-years from Earth, it is one of the closest star-forming nurseries to us. It’s enormous. Under a very dark sky, the nebula can be traced over an area equivalent to four full moons! When you see knots of pink color in photos of other galaxies, you are seeing objects like M42.

Buried in the core of the nebula is a tight clump of stars collectively designated Theta Orionis (Orionis is Latin for “of Orion”), but better known as the Trapezium – because the brightest four stars occupy the corners of a trapezoid shape. Even a small telescope should be able to pick out this four-star asterism – but good seeing conditions and a larger aperture telescope will show two additional faint stars. The trapezium stars are hot young O- and B-type stars that are emitting intense amounts of ultraviolet radiation. The radiation causes the gas they are embedded in to shine brightly, by both reflecting off gas and dust as blue light and also by energizing Hydrogen gas, which is re-emitted as red light. That is why there is so much purple and pink in colour images of the nebula.

Within the nebula, astronomers have detected many young (about 100,000 years old) concentrations of collapsing gas called proplyds that should one day form future solar systems. These objects give us a glimpse into how our sun and planets formed.

Stargazers have long known about the stars in the nebula’s core, but detection of the nebulosity around them required the invention of telescopes in the early 1600’s. In the 1700’s, Charles Messier and Edmund Halley (both famous comet observers) noted the nebula in their growing catalogues of “fuzzy” objects. In 1880, amateur Henry Draper imaged it through an 11-inch refractor telescope, making it the first deep sky object to be photographed.

In your own small telescope, you should see the bright clump of Trapezium stars surrounded by a ghostly grey shroud, complete with brighter veils and dark gaps. More photons would need to be delivered to your retina before colour would be observed, so try photographing it through your telescope, or using a camera/telephoto lens on a tripod. Visually, start with low magnification and enjoy the extent of the cloud before zooming in on the tight asterism. Can you see four stars, or more? Just to the upper left of M42, you’ll find M43, a separate lobe of the nebula. It surrounds the unaided-eye star nu Orionis (or ν Ori).

While you’re touring the sword, look just below the nebula for a loose group of stars, located 1,300 light-years away from Earth, called Nair al Saif “the Bright One of the Sword”. The main star is a hot, bright star expected to explode in a supernova one day. It is surrounded by faint nebulosity, too. Astronomers believe that this star was gravitationally kicked out of the Trapezium cluster in Taurus about 2.5 million years ago.

Sweeping down the sword and toward the left (east) brings us to the star named Mizan Batil ath Thaalith (or d Orionis) at the tip of the sword. This magnitude 4.7 star is near the limit for visibility in moonless suburban skies. About two finger widths to its right is another star of similar brightness, named Thabit, “the Endurer”.

Moving upwards towards Orion’s belt, half a finger’s width (30 arc-minutes, or the moon’s diameter) above the Orion Nebula, you’ll find another clump of stars dominated by c Orionis and 45 Orionis. A larger telescope, or a long-exposure photograph, reveals a bluish patch of nebulosity around them that contains darker lanes forming the shape of a figure, called the Running Man Nebula. This is another case of gas reflecting light from the two stars mentioned.

Just above the Running Man sits a loose cluster of a few dozen stars best seen in binoculars. Then we jump higher – most of the way towards Alnitak the eastern-most (left-hand) belt star, to check out a beautiful little grouping of stars collectively called Sigma (σ) Orionis. What makes this a special treat is that, in a small telescope, we find four or five stars crammed together. Check it out with your telescope – trust me, it’s pretty! It’s a bit more than a finger’s width to the lower right of Alnitak. Let me know what shape you see!

Treats in Taurus

If you missed last week’s tour of Taurus (the Bull), I posted it here.

Binocular Comet Update

A relatively modest comet is traversing the northeastern evening sky this winter – and this week will be ideal for hunting it! Designated C/2017 T2 (PanSTARRS), after the robotic telescope it was discovered with, the comet is currently shining at magnitude 8.4. That means that it is conveniently positioned for evening viewing in good binoculars or a backyard telescope. I posted a sky chart showing its path over the next month here.

The comet is very high up the northern sky after dusk – and it moves even higher in mid-evening as the Earth’s rotation carries the sky east to west. Comets move across the background stars faster than planets wander. This week, the comet will be just inside the northern boundary of Perseus (the Hero). If you face north, the comet will be located to the lower left of Mirfak, Perseus’ brightest star, and a fist’s width to the upper right (or 10° to the celestial northwest) of the star Ruchbah in Cassiopeia (the Queen). Ruchbah marks the top of the shorter peak of Cassiopeia’s “M”-shape.

Over the next seven nights the comet will move a distance of less than two finger widths of sky, in the direction of Cassiopeia. At the same time, the comet will pass less than a finger’s width (1°) below the famous Double Cluster. That close-together pair of clusters is visible to unaided eyes under dark skies and is very easy to spot in binoculars from the city – making finding the comet very easy to find all week.

When viewed in binoculars and telescopes, Comet PanSTARRS will appear as a dim, fuzzy patch that might exhibit a faint greenish centre. It’s a bit early to see a tail, but the comet is expected to brighten much more in the coming months. Stay tuned for updates!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Taking advantage of dark, moonless evening skies this week, astronomers with the RASC Toronto Centre will gather for dark sky stargazing at Long Sault Conservation Area, northeast of Oshawa on (only) the first clear evening (Monday to Thursday) this week. You don’t need to be a RASC member, or own any equipment, to join them. Check here for details and watch the banner on their homepage or their Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Registration and details are here.

This winter, spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday, February 9, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 2 pm, and repeat from 2 to 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older. The Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible, but everyone else sits at floor level. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!