A Northerly Rise for the Full Frost Moon, a Meagre Maximum for Mercury, Lots of Spots Cross Jupiter, and a Couple of Comets!

A rotating model of Saturn’s moon Iapetus. Its variation in surface brightness causes it to change in apparent brightness as it travels around Saturn over 80 days. On November 29, 2023, Iapetus will appear brighter as its reaches it western elongation. (Wikipedia)

Hello, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 26th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will reach its full phase tonight and continue to flood the evening sky worldwide with light until the coming weekend. Making lemonade of that, I share some interesting sights to see on the moon. The moon will also rise at its farthest north azimuth in almost 20 years. Once the moon leaves evening, a couple of interesting comets will be available for viewing. Venus will gleam before dawn, Mercury will stretch farthest from the sun after sunset, evening Jupiter will be frequently crossed by the shadows of its moons, and Saturn’s moon Iapetus will peak in brightness. Read on for your Skylights!

Comets Update

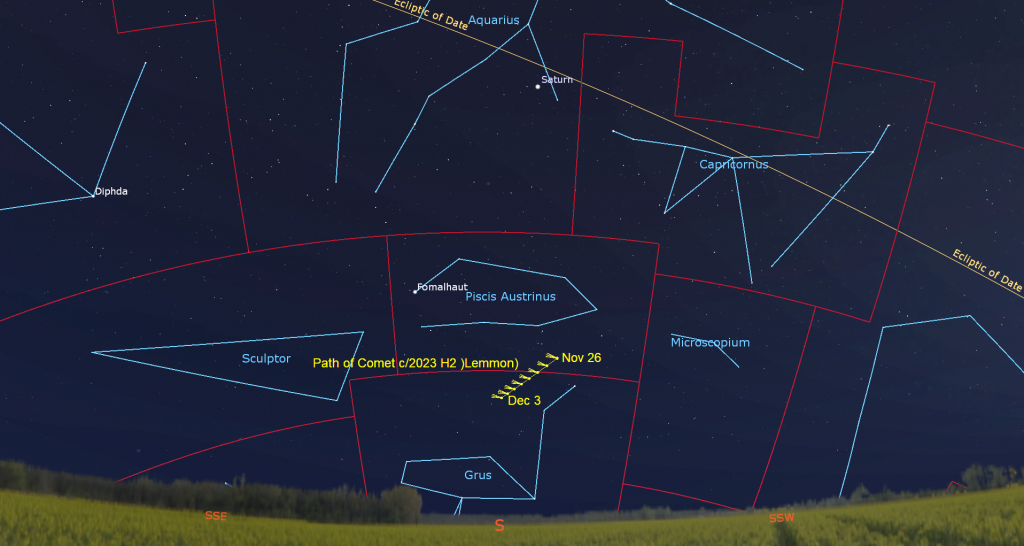

Comet c/2023 H2 (Lemmon) peaked in size and brightness around November 10, but it is still within reach of backyard telescopes under dark skies for another week or so. Unfortunately, it’s too low in the southern sky for clear views from Canada and the northern USA (and similar latitudes worldwide). This week it will be travelling well below Saturn, along the border between the constellations of Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish) and Grus (the Crane). That part of the sky only climbs nice and high for observers living near the tropics or Southern Hemisphere.

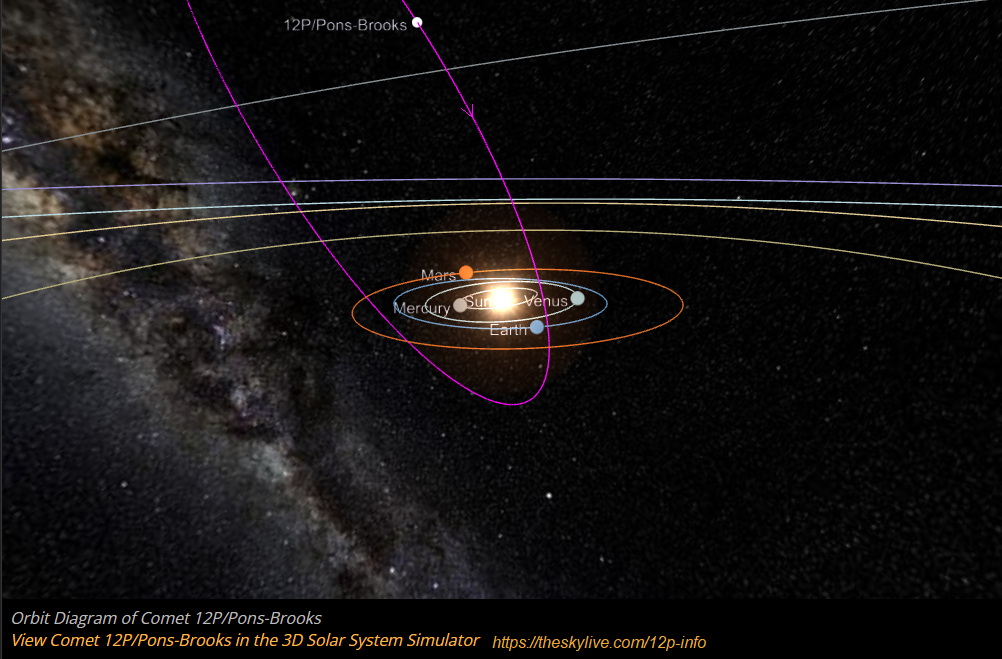

Another comet named 12P/Pons-Brooks was discovered by Jean-Louis Pons in 1812 and then rediscovered by William Robert Brooks in 1883. Similar to Halley’s comet, it ventures into the inner solar system and passes just inside the orbit of Earth every 71.3 years. Then it heads out beyond the realm of Neptune and Pluto for decades. Its orbit is nearly at right angles to the plane of our solar system, so it would be an excellent candidate for a spacecraft to hitch a ride on, allowing us to sample space around the planets and view the sun and planets’ polar regions, albeit slowly. I’ll post a diagram of that geometry here.

Comet Pons was forecast to become brightest next spring. It will get closer to Earth starting in mid-February, reach maximum out-gassing activity while near the sun at perihelion on April 21, and then become largest in the sky when it passes closest to Earth on June 2. During that window of time, it might become visible to our unaided eyes in the evening sky.

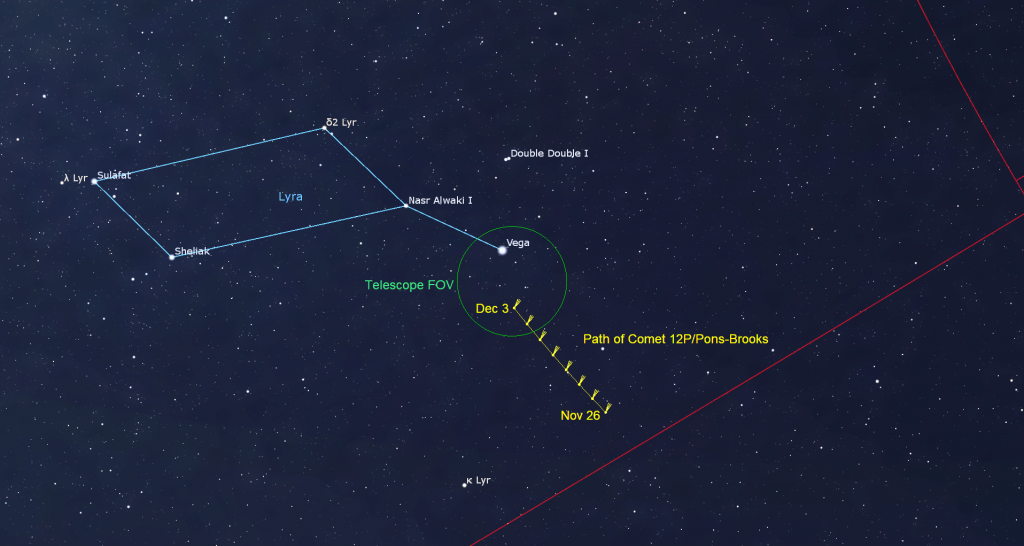

The comet has unexpectedly brightened ahead of schedule, in what astronomers call outbursts. Reports have come in that its visual magnitude has jumped to around 9.5, allowing us to see it as a faint, fuzzy smudge in backyard telescopes under dark skies. We don’t know if it will fade again or maintain its appearance. The comet is very easy to find! This week, it will be travelling toward the very bright star Vega, which dominates the western sky every evening. I’ll post finder charts for both comets here. You’ll want to wait a few nights for the bright moon to leave the early evening sky.

The Moon

The moon will brighten our nights for the first part of this week while it passes its full phase. By the time we get to next weekend, though, the December dark sky viewing period will be upon us. Hello, Orion Nebula!

The moon will look full at a glance tonight (Sunday night) in the Americas, but binoculars or your telescope will reveal that a sliver along its left-hand (lunar western) edge is “missing” and that the craters there will show some texture. The moon will reach its precisely full phase at 4:16 am EST, 1:16 am PST, or 09:16 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday morning, November 27.

Since it’s opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, the moon becomes fully illuminated, and rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes reach as high in the midnight sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows from the trees and structures in your backyard. Lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation, so they can happen at any time of the night or day. For this full moon, only folks living at longitudes near France or Ghana will see the moon exactly full when it rises.

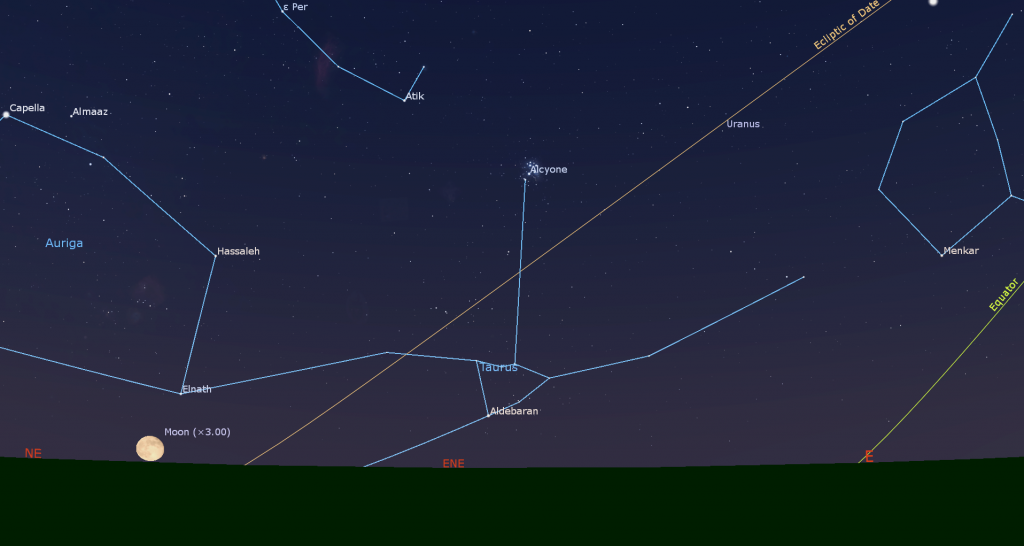

The November full moon, traditionally known as the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Taurus (the Bull) and Aries (the Ram). Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizisoonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Freeze Up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon. With this full moon occurring on the boundary between modern calendar months, which were not employed by indigenous groups, it might be more appropriate to use their December moon names. But I’ll wait until next month to share those.

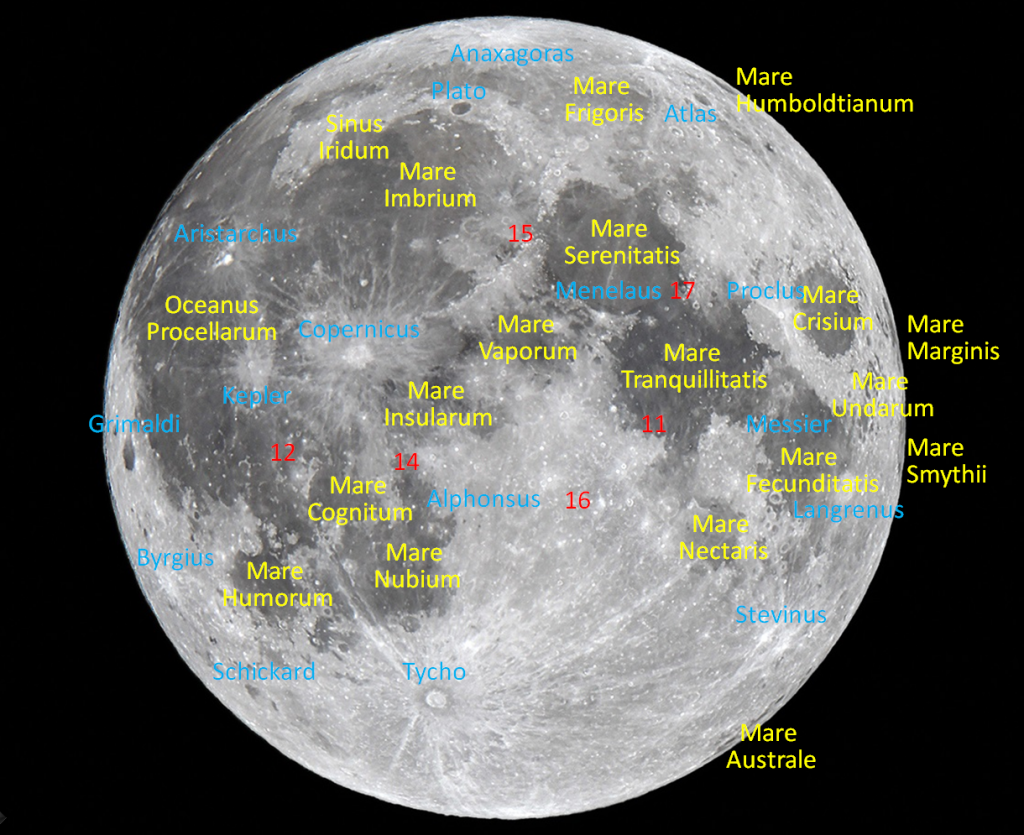

When the moon is fully illuminated, no shadows are cast by its topography – so the moon’s geology is enhanced, especially the contrast between the ancient bright and heavily cratered highlands and the younger, smoother, dark maria (Latin for “seas”). The maria are basins that were excavated by large impactors early in the moon’s history. They only cover about 16% of the moon’s entire surface area – but almost all of them are on the Earth-facing hemisphere. Some planetary scientists theorize that the Earth’s surface was molten for an extended period of time after the violent collision that formed the moon. Shortly after the moon coalesced into a sphere, the stronger tidal force of Earth’s gravity slowed the moon’s rotation to its present once-a-lunar-month rate, making it keep the same face towards Earth at all times. The heat of Earth then “cooked” the moon’s near side, allowing the lunar crust to remain soft and permeable so that dark magma could leak out from the depths and fill in the basins.

The terms “maria” and “terra” were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope around 1610. The rest of the moon’s naming system was developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli. In 1651 he published a labeled moon map with names that modern maps are based upon. He used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together.

The maria are all named for weather and states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers after Riccioli’s time, and Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical (to him) proponents of the heliocentric theory of the solar system, Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler, in the Sea of Storms. He honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters.

Grab your binoculars and look for the many ray systems spreading across the full moon’s face. The rays are composed of material that has been thrown radially outwards when objects that slammed into the moon created its more recent craters. The rays are particularly apparent when the moon is lit face-on, as it is around the full phase. Viewed in a telescope, major rays can be shown to be chains of small secondary impact craters excavated by the falling chunks of excavated rock (or ejecta), and by the scattered debris itself. Impacts on the light-coloured lunar highland rocks tended to spread white rays over the surrounding darker mare regions – but sometimes the inverse happens.

Some ray systems are enormous – spanning half the moon’s disk! The ray system of the crater Tycho is a fine example of that. Tycho is the very bright crater located in the south central part of the moon. Its rays are largely missing on the left-hand (lunar western) side, suggesting that its impactor, an asteroid 8 to 10 km in diameter, arrived from the west at an angle less than 45° above the lunar surface, throwing the ejecta in front of it, mainly to the east. In a telescope, you can see that Tycho is encircled by an asymmetrical dark blanket of rubble that is about as wide as the crater’s 85 km diameter. The dark colour is probably basaltic rock excavated from deep below the crust. Tycho and its rays are bright because it is a relatively young crater – only about 109 million years old. The dinosaurs were walking the Earth when the violent event happened! It’s too bad they couldn’t leave us a record of what they saw!

The small crater Proclus is located at the lower left edge of Mare Crisium, the round grey basin near the moon’s upper right edge (northeast on the moon). Proclus’ bright rays only extend toward the right-hand side of the crater, mainly onto Crisium – again due to a very shallow impact trajectory. Many of the dark maria have a single white ray crossing them. Can you trace them back to their origin?

When the moon rises a while after sunset on Monday night, it will still look full – but now a narrow arc along its right limb will be darkened and the bordering craters highlighted. As the moon’s orbit carries it sunward again after the full moon, it will rise about 45 minutes later each night and wane in phase. On Tuesday evening, the still nearly full moon will be positioned near the point on the ecliptic that is farthest north of the celestial equator. (That’s where the sun always sits at the June solstice.) On the same night, the moon will be an additional 4.3° north of the celestial equator. It can do that because the moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5° compared to Earth’s orbit. All that will combine to make the moon rise on Tuesday at a point on the horizon that is about as far north of east as it ever does, and then climb very high in the sky in the middle of the night. The phenomenon repeats about every 19 years, so it’s worth a peek.

After completing its passage through Taurus’s stars on Monday and Tuesday, the gibbous moon will spend Wednesday and Thursday crossing Gemini (the Twins). The moon will pose near Gemini’s brightest star Pollux on Thursday night. The other “twin”, the excellent double star Castor will shine above them. As the trio crosses the sky together during the night, the moon will drift farther from Pollux and make a bent line with Castor in the southwestern sky before dawn on Friday. If you have difficulty seeing the stars, position the bright moon beyond the left edge of your binoculars field of view. Once the sun rises, the stars will disappear, leaving the pale moon to haunt the morning daytime sky like an echo of the night.

On Friday evening, the 77%-lit moon won’t clear the eastern treetops until about 9:30 pm local time, so you can squeeze in a little moonless stargazing right after dinner. That night, the bright moon will overwhelm the relatively faint stars of Cancer (the Crab) that surrounds it. The moon will end the week by charging into Leo (the Lion). By the time we reach next Sunday night, the football-shaped moon will be shining near Leo’s brightest star Regulus when they rise towards 11 pm local time. I’ll focus on some nice treats for moonless evenings next week.

The Planets

The planet Mercury has been positioned over the southwestern horizon right after sunset for the past week or two, but its position below a very slanted ecliptic has held it too low to be seen easily from mid-northern locales. On Monday, Mercury will extend to its widest separation of 21 degrees east of the Sun, and give it maximum visibility for its current evening apparition. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes then will start around 5 pm local time, but the magnitude -0.44 planet will still pose a challenge. Don’t worry, though. Mercury returns to view every 45 or 73 days, so there will be fine chances to see it in January and March. If you live in the southern USA, or in the tropics or the Southern Hemisphere, you can seek out Mercury’s brightening speck above the sunset point on the horizon after the sun has completely set this week – but don’t search with binoculars or a telescope until the sun is gone from view. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waning gibbous phase.

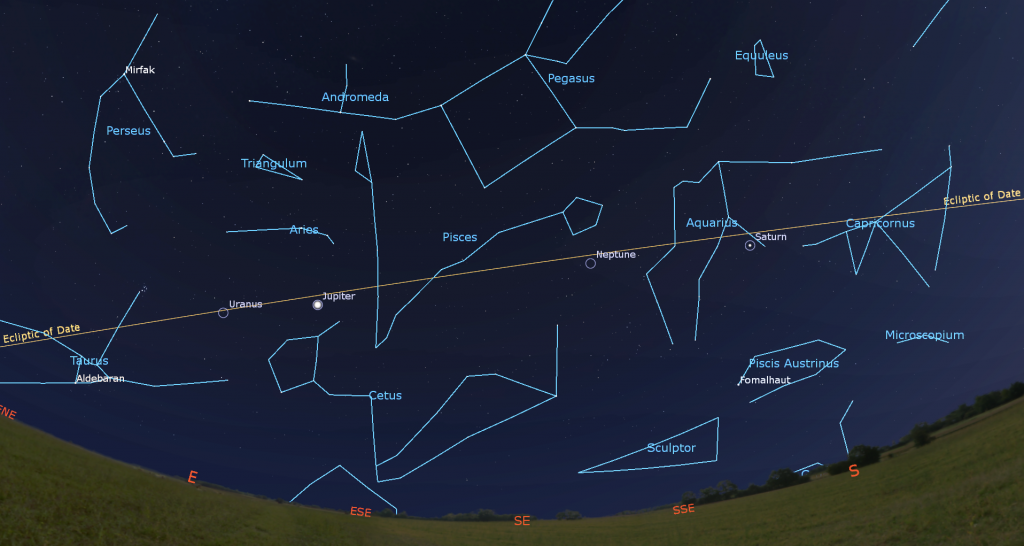

Don’t go indoors after you’ve finished with Mercury. Look well up the western sky to see the summer’s brightest star Vega and make a wish! Next, turn to the southeast and look for Saturn’s warm-white dot positioned about one-third of the way up the southern sky, then bright, white Jupiter gleaming lower over in the east.

Saturn will climb to its highest point, or culminate, in the south around 6 pm local time (its best telescope viewing time) and then sink westward to set after 11 pm. This week’s bright moon will interfere with seeing the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) arrayed to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east) and the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) to Saturn’s lower right (or west). Saturn will remain within the bounds of Aquarius until early April, 2025.

Good binoculars can show that Saturn has rings, but any size, style, or brand of telescope will show their beauty. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady (we call that good seeing), try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the large outer A Ring from the large inner B Ring. I wrote more about the rings here.

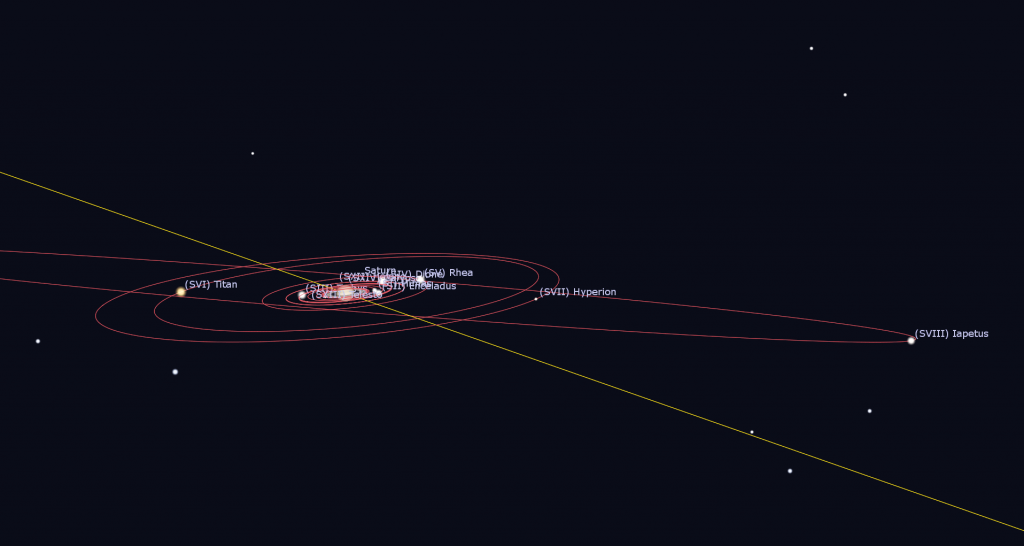

From Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. Half of Iapetus is coated with dark soot, so it alternatively brightens and dims every five weeks as those two hemispheres take turns pointing toward Earth. Iapetus appears brightest when it is farthest to the west of Saturn, which will happen on Wednesday.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from just to the upper right of Saturn (or celestial northwest) tonight to a position farther left of the planet (or celestial southeast) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

The far fainter ice giant planet Neptune is following Saturn across the sky each night, but the bright moonlight will make finding it and seeing it difficult.

As I mentioned above, the giant planet Jupiter will gleam above the eastern horizon at sunset and then catch your eye while it crosses the sky all night long. Jupiter will climb to a position relatively high in the southern sky around 10 pm local time and then set in the west by 5 am local time. The big planet will look best in a telescope while it is higher, between dusk and 2:30 am each night. After the bright moon departs the scene late this week, the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) named Hamal and Sheratan, can be spotted shining a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter.

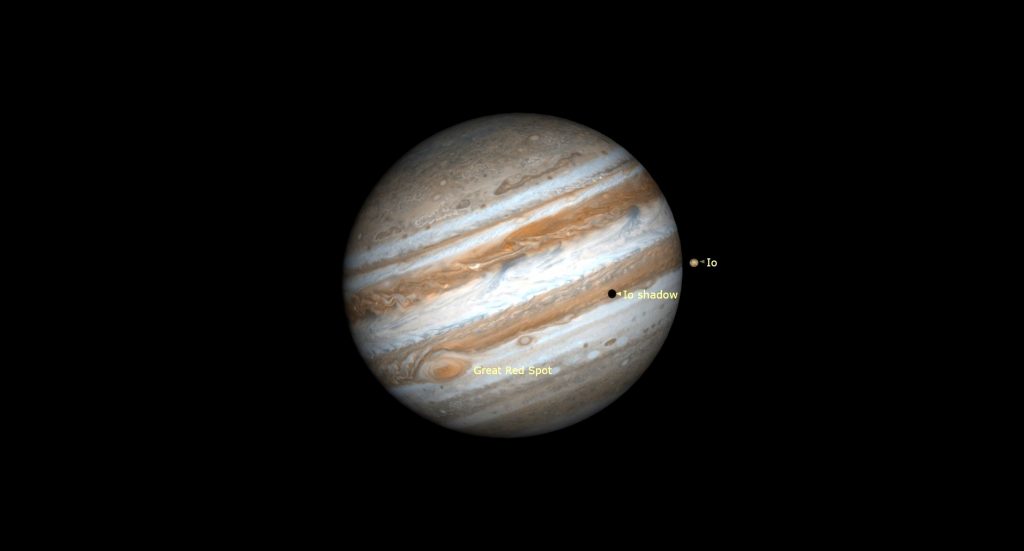

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line flanking the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will be gathered to Jupiter’s left next Sunday.

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday. It’ll appear late night Tonight (Sunday), Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday, and also before dawn on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday night, November 27, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 11:13 pm to 1:20 am EST (or 04:13 to 06:20 GMT on Tuesday). Europa’s tiny shadow will cross on Tuesday evening, November 28 from 5:21 pm to 7:38 pm EST (or 22:21 to 00:38 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again on Wednesday evening, November 29 from 5:41 to 7:49 pm EST (or 22:41 to 00:49 GMT). Ganymede’s large shadow will travel across Jupiter’s southern latitudes on Saturday morning, December 2 from 1:13 am to 2:42 am EST (or 06:13 to 07:42 GMT). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Like Neptune and Saturn, Uranus has been following Jupiter across the sky every night this year. This week the blue-green ice giant planet will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s lower left (or 13° to the celestial east) in eastern Aries. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus to the same height as Jupiter around 10:15 pm local time and then higher still later on. At magnitude 5.63, Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes – some people have even been able to spot the planet with their unaided eyes. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will also be located a fist’s width to Uranus’ left (or 10° to the celestial northeast), but the bright moon this week will hinder seeing much other than Jupiter.

Venus, the brightest planet of them all, will be rising among the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) at about 3:40 am local time this week. If you head outside by about 6 am on a clear morning, Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, will be sparkling in the southwestern sky, a mirror to Venus’ “Morning Star”. Due to its swing sunward, Venus will drop a little lower each morning. Over the course of this week, it will descend through Virgo, passing her brightest star Spica on the left. Viewed through a telescope, our next-door planet will show a waxing gibbous disk spanning 17.9 arc-seconds.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!