A Puny Blue Blood Halloween Moon marks Mid-Autumn, and Bright Planets on View from Evening to Dawn!

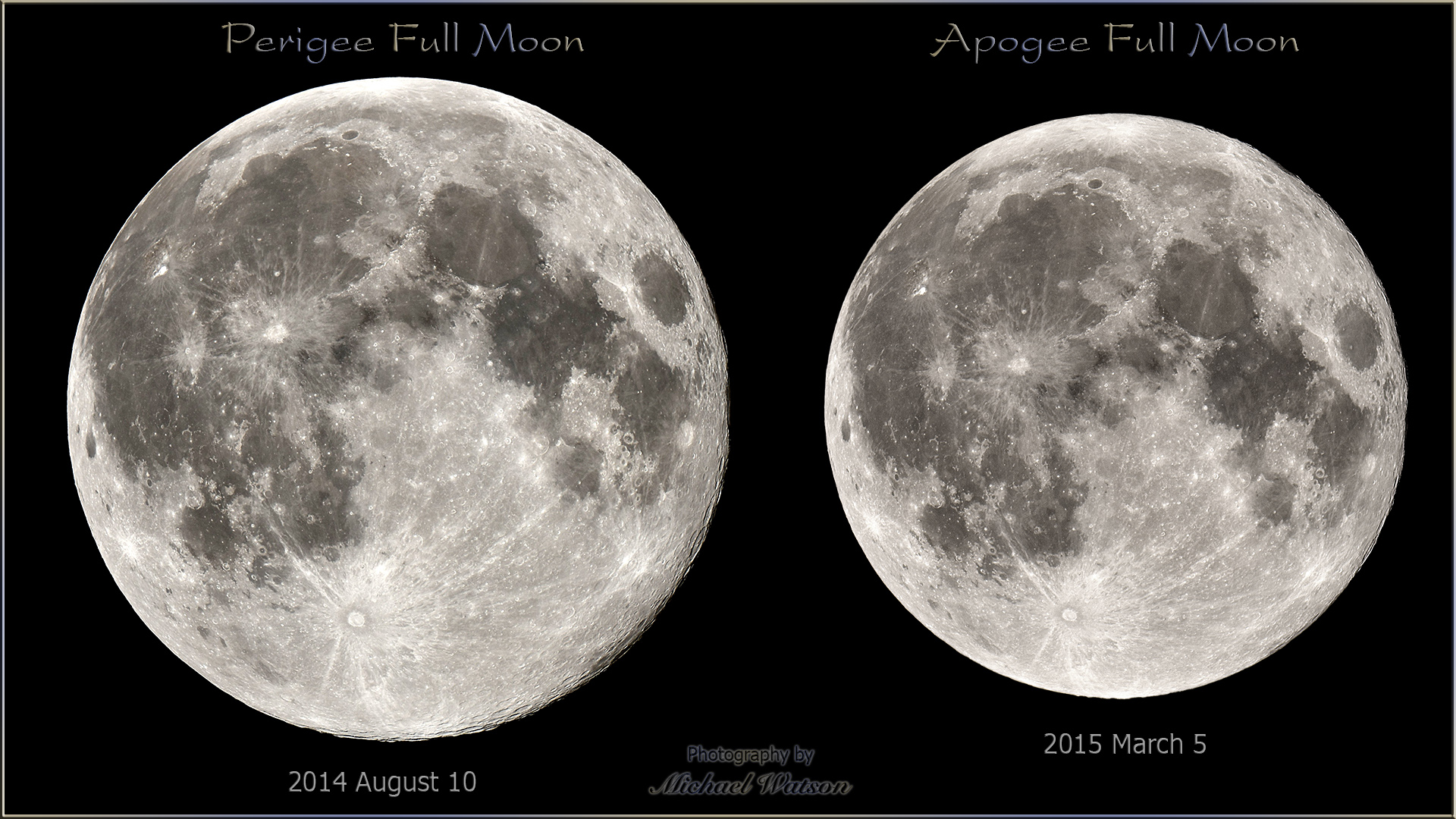

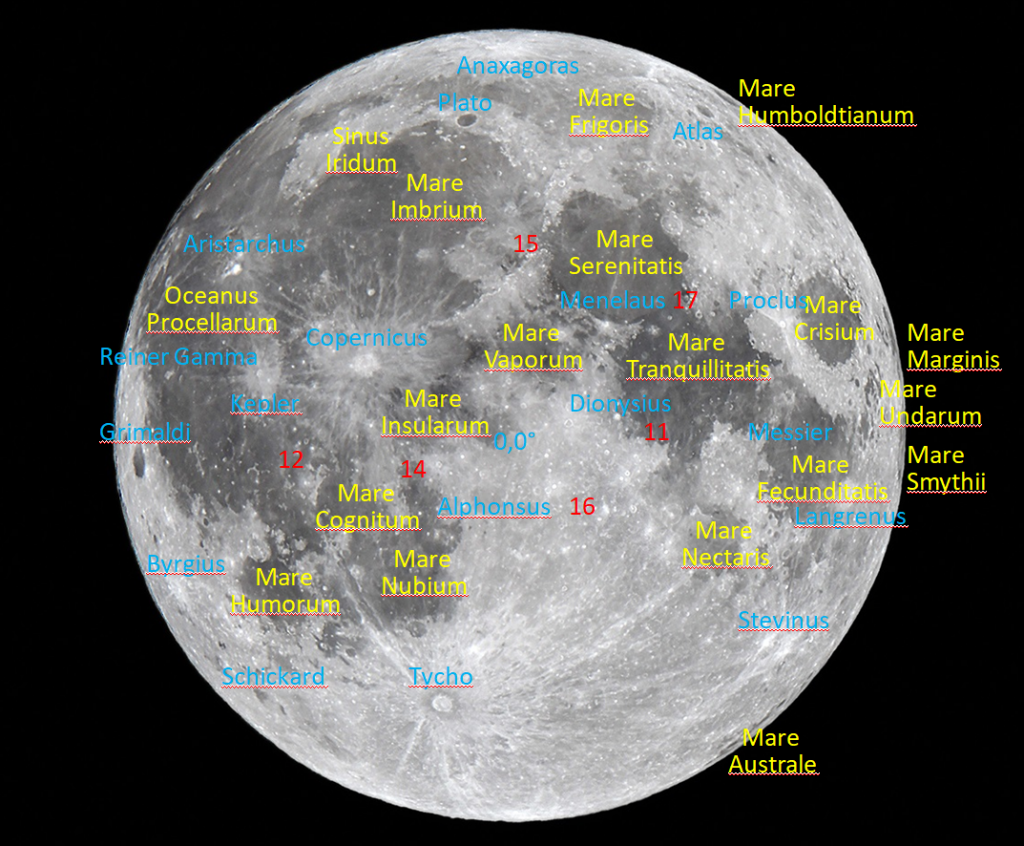

These images of the full moon by Michael Watson of Toronto perfectly illustrate the size difference between a perigee “supermoon” and an apogee “punymoon”. The image on the right will very closely conform to the appearance of the full moon on Halloween night – when the moon will actually be about 10 hours past full – causing the craters along the eastern (right-hand) limb to exhibit some shadows. Michael’s Flickr galleries of wonderful astro-images can be viewed online here.

Hello, mid-Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 25th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To see the pictures more clearly, right-click and save them to your computer, and to subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

With mid-autumn arriving, the evening moon will take centre stage around the world this week as it waxes from first quarter to a full blue punymoon on Halloween. I highlight some sights to see on it. Meanwhile Mars continues its splendid evening showing, Jupiter and Saturn shine during early evening, and Mercury joins Venus before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

Don’t forget to set your clocks back an hour next Sunday, November 1!

It’s Mid-Autumn!

Halloween, or All Hallows’ Eve, has been pinned to the date of October 31 every year. It actually originated from Samhain, a festival observed by the ancient Celts and Druids to mark the end of harvest season and the beginning of winter weather – pagan Thanksgiving, if you will. Astronomically speaking, samhain is one of the four cross-quarter days, the season midpoints that occur halfway between each solstice and equinox.

In modern times, observers of Samhain celebrate on November 1 – but the true mid-point of autumn will occur on November 7. At that time, the ecliptic longitude of the sun will be 225° – extremely close to the double star Zubenelgenubi in Libra (the Scales). The other three cross-quarter days are Groundhog Day (or Imbolc) on February 2, May Day (Beltane) on May 1, and Lughnasath or Lammas on August 1.

You can’t merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day seasons and then count half that many days to reach the cross-quarters. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving slower at aphelion in July, summers in the Northern Hemisphere are about five days longer than winters!

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when our celestial dance partner will shine brightest in the evening sky worldwide. After Friday’s last quarter phase, the moon will continue to wax fuller and rise later each night while it wades eastward through the modest stars of the water constellations – first Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and then Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes). Keep your binoculars and telescopes handy – because for most of this week, the lunar terrain will be dramatically lit by low-angled sunlight, especially along the pole-to pole terminator that divides the lit and dark hemispheres. Below, I’ll describe some highlights to look for on the moon.

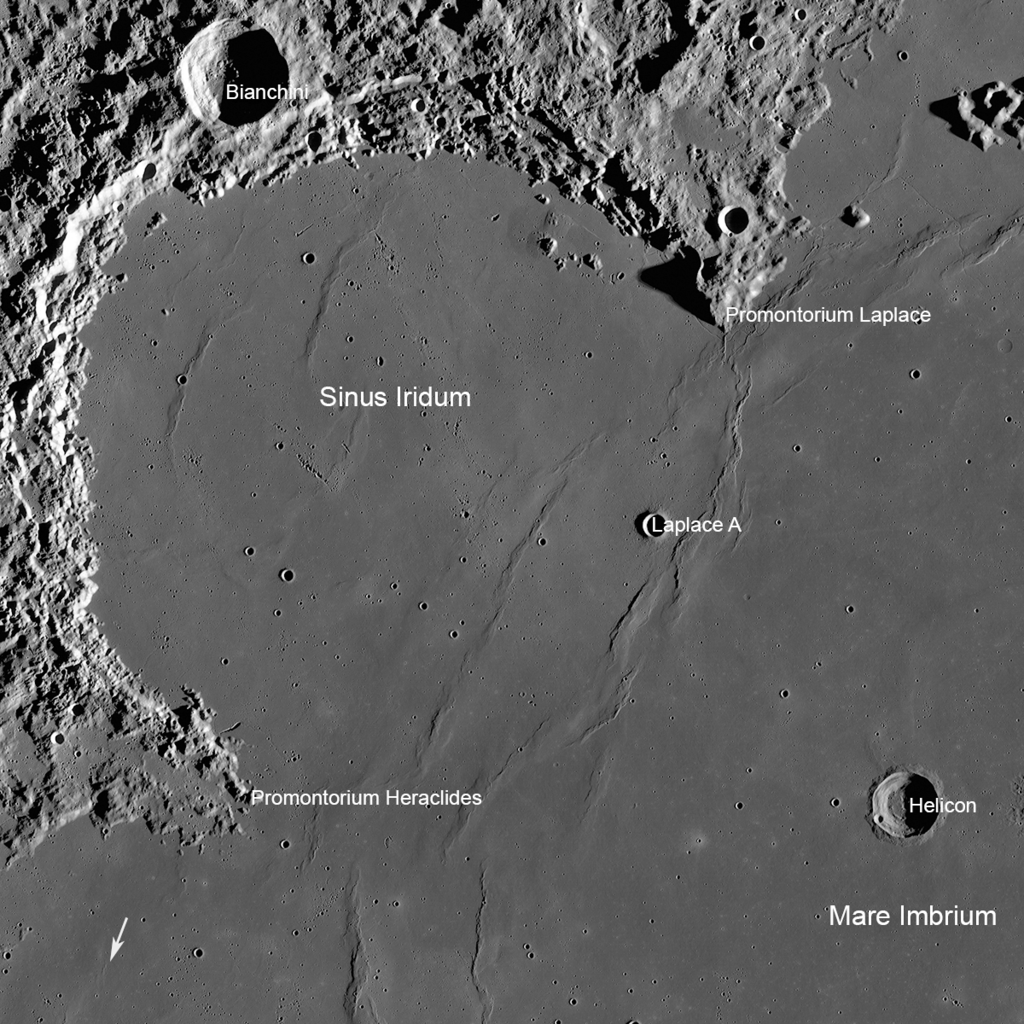

On Tuesday night, terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it easily with sharp eyes and binoculars. The “Golden Handle” effect is produced by the way slanted sunlight brightly illuminates the eastern side of the prominent Montes Jura mountain range that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west), and by a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace to the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed in a telescope at this phase.

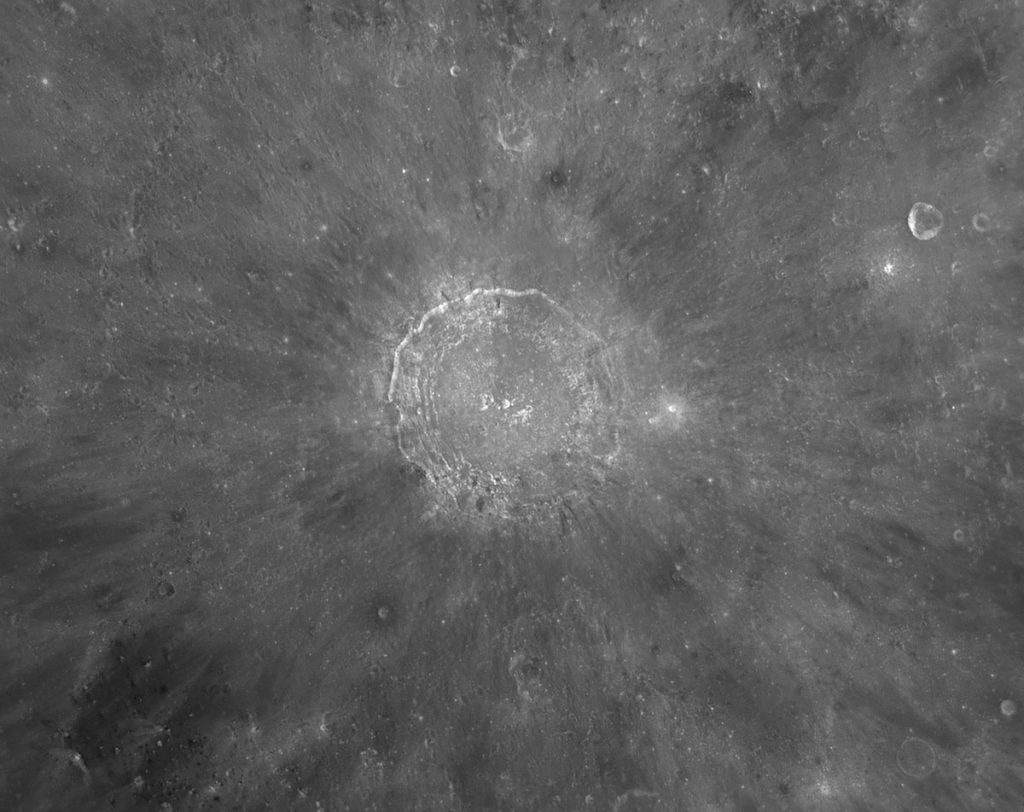

Look for the prominent crater Copernicus in eastern Oceanus Procellarum. It’s well below the Golden Handle and Mare Imbrium, and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. This 800 million year old feature is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus will exhibit heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – caused by impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

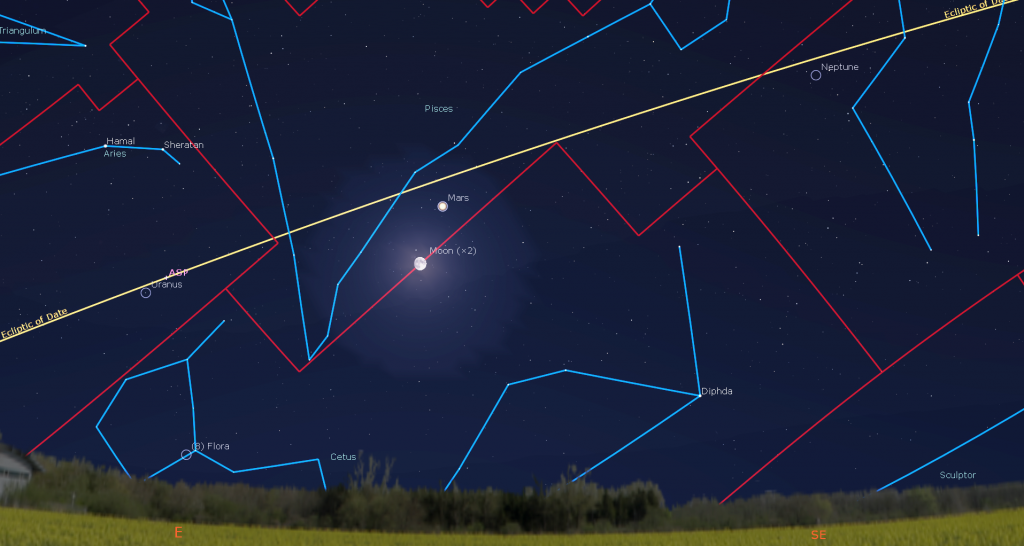

In the eastern sky after dusk on Thursday evening, the nearly full moon will be positioned several finger widths below (or 4 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Mars – close enough for them to appear together in most binoculars. As the duo crosses the sky together during the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky, and the moon’s eastward orbital motion, will combine to shift the moon clockwise around Mars – placing it a generous palm’s width to the upper left of the red planet in the western sky by sunrise on Friday morning.

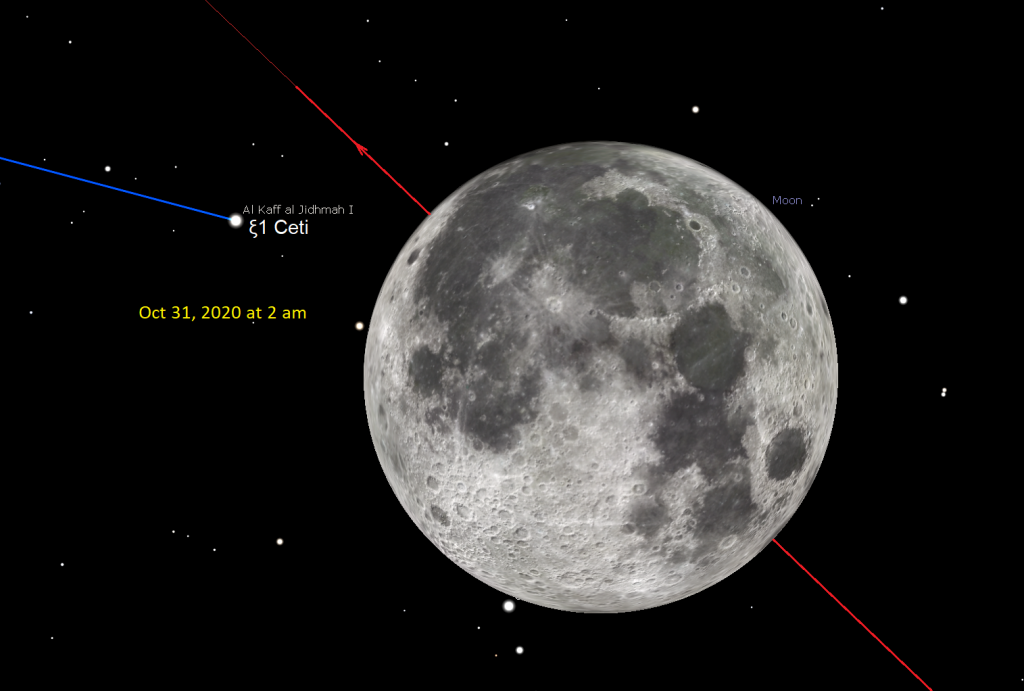

After midnight on Friday, October 30, observers using binoculars and backyard telescopes in most of North America can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) the medium-bright star designated Xi1 Ceti (or ξ1 Ceti). That magnitude 4.35 star, which some apps call Al Kaff al Jidhmah I, marks the top of the head of Cetus (the Whale). In the Great Lakes region, the thin strip of darkness along the leading edge of the nearly full moon will move over the star at approximately 2:37 am. The star will emerge from behind the lit side of the moon, near the moon’s bottom, at about 3:27 am EDT. Ingress and egress times vary based on your latitude, so start watching a few minutes before the times quoted above – or use a planetarium app to look up the exact times for your town.

On Saturday at 10:49 am EDT, the second full moon of October will occur. Since the full phase will occur on Saturday morning in the Eastern Time Zone, folks there will see that the moon is slightly less than full on Friday night, and slightly past full on Halloween night. Use your binoculars or telescope to look for some texture in the craters along the moon’s left-hand (western) rim on Friday and along its right-hand (eastern) rim on Saturday. Only people living in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Eastern Africa will see the moon rise when it’s exactly full.

This full moon is traditionally called the Hunter’s Moon and, appropriate for Halloween, the Blood Moon, or Sanguine Moon. Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the October moon Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon – the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

This full moon will occur only 20 hours after reaching its greatest distance from Earth, or apogee – producing the smallest full moon of 2020. The opposite of a Supermoon – perhaps this one should be called a Punymoon! Because the last full moon occurred on October 1, this second one during the month will be a “Blue Moon” – but the moon will not sport any unusual coloration.

When you face a full moon, the sunlight shining on it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on the full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! Now you can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then later infilled with dark basaltic rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon. There are smaller ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters punched into the maria have ejected dark rays on to white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock below, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enrichment in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to that location.

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than a lunar module descent stage. Only the cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment.

The Planets

Before 7 pm local time this week, very bright, white Jupiter will pop into view in the lower part of the southern sky. A short time after that, dimmer, yellowish Saturn will appear a palm’s width to Jupiter’s left (or 6 degrees to the celestial east). Faster Jupiter is chasing slower Saturn and will pass it in spectacular fashion on December 21! For now, our season of clear views of those two planets is closing. After 9 pm local time, they will be getting low in the southwestern sky, and shining through a much thicker blanket of Earth’s atmosphere. You might even see them twinkle a bit in late evening! Thankfully, the earlier sunsets are allowing us to start viewing them earlier each night.

Good binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. Even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short) – if the air is steady. Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour period of rotation, the GRS will appear every second or third night at your location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday.

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. On Sunday, November 1 from 5:35 pm (dusk in the Eastern Time Zone) to 9 pm EDT, Ganymede’s large shadow will travel across Jupiter. The event will be visible anywhere on Earth where Jupiter is above the horizon during the time windows (adjusted to your local time zone). Other places will see different transits.

Saturn is a spectacular sight in any backyard telescope. Even a small one will show you Saturn’s rings. In a telescope, the rings are almost as almost as wide as Jupiter’s disk. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

Your telescope should also reveal several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. The trick for seeing more moons is to watch continuously for a minute or two, and let the dimmer, closer-in moons appear whenever the air stabilizes. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the right of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.) Fun fact: There’s a Mount Doom on Titan!

Mars is still a great evening target! This week, very bright, reddish-tinted Mars will be rising in the east before 6 pm in your local time zone. It will climb to its highest point – a bit more than half-way up the southern sky at about midnight local time, and then set in the west before sunrise. Viewed in a telescope this week, Mars will display the dark Acidalia Planitia, Terra Sirenum, and Aurorae Planum regions, and the bright Tharsis region. The latter hosts the giant volcano Olympus Mons and the solar system’s largest canyon, Valles Marineris.

Because Earth is passing Mars on the “inside track” of the solar system, Mars is moving retrograde, causing the planet to appear to travel westward compared to the narrow “V” of modest stars at the bottom of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). You won’t see that motion unless you carefully note the positions of Mars and the surrounding stars changing over several nights.

By the time the sky is fully dark, the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune will be above the horizon, too. Blue-green Uranus will cross the sky among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram). It is located a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. That region of the sky is two fist diameters to the lower left (or 20° to the celestial east) of Mars. Uranus will reach opposition on Saturday. On that night it will be closest to Earth for this year at a distance of 2.81 billion km, or 156 light-minutes. Its minimal distance from Earth will cause it to shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.7 and to appear slightly larger in telescopes for a few weeks. Try for Uranus after 9 pm, when it will be higher in the sky. I posted a detailed star chart for Uranus here.

Neptune, which rises in late afternoon, is located among the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), about two finger widths to the left (or 2 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, Neptune will already be in the lower southeastern sky after dusk. Then it will climb higher until 10 pm local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s almost halfway up the southern sky. I posted a detailed sky chart for Neptune here.

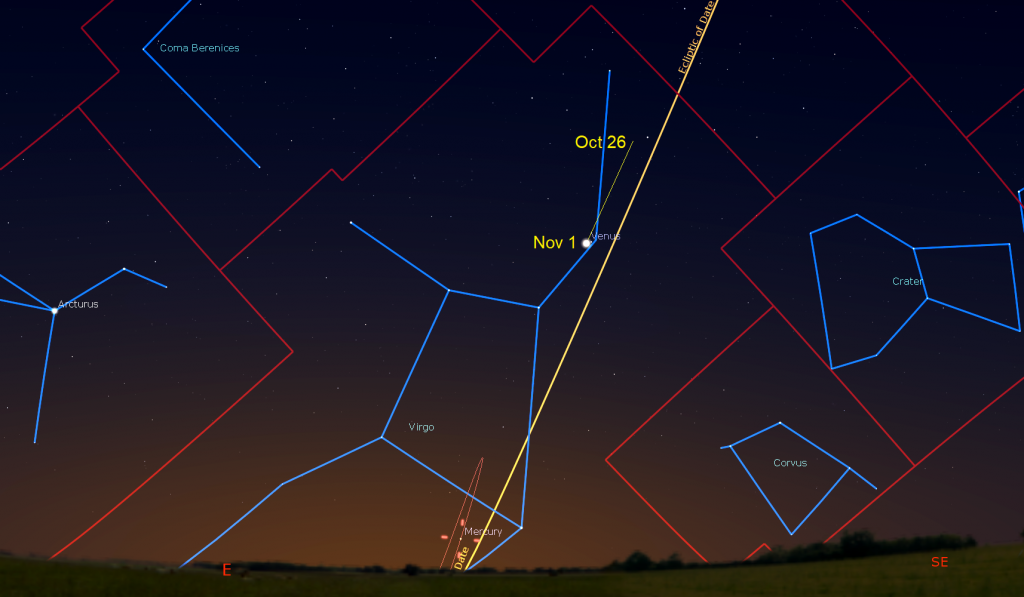

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now. It will rise at about 4:45 am local time this week, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a gibbous, 80%-illuminated shape. This week, the planet will be traversing the stars of Virgo (the Maiden). Venus is shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will allow it to shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until early December! And while you’re taking in the show, enjoy a view of the extremely bright star Sirius, and the winter constellation of Orion (the Hunter) sitting well off to Venus’ upper right.

By next weekend, you can start looking for speedy little Mercury sitting just over the east-southeastern horizon before dawn. It’s the beginning of an excellent Mercury-viewing window for everyone at mid-northern latitudes.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 28 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature the fantastic Paul A. Delaney, University Professor, Allan I. Carswell Chair for the Public Understanding of Astronomy, York University. His talk, entitled Water, water everywhere?, will address how we search for water in the solar system. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here. The RASC Toronto Centre has an archive of their past meetings and guest lectures on their YouTube Channel here.

On Wednesday evening, October 28 at 6 pm EDT, U of T’s Astronomy & Space Exploration Society (ASX) will host a free public Zoom broadcast called The New Era of Radio Astronomy. Details and the Zoom link are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, November 17 – with the topic TBD. (Send us suggestions!) You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here. Don’t forget to tune in to Jenna and John Reid’s final RASC Explore the Universe certificate livestream on Thursday, October 29 at 3:30 pm EDT.

On Saturday night, October 31 from 8 to 10 pm, join me as I co-host the Ontario Science Centre’s bewitching and spell-binding Halloween Virtual Star Party on YouTube here. We’ll have live views of the moon, planets, and spooky deep sky objects. More details are here.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!