A Spotty Sun, Morning Luna’s Silver Sliver, Dotted Jupiter and Ringed Saturn Ride the Sea-Goat, and Looking at Lyra!

This full-disk image of the sun in visible wavelengths was taken by the Solar Dynamics Observatory satellite on August 29, 2021. It shows the huge sunspot group designated AR2860 that is currently visible by anyone using safely filtered telescopes, pinhole projectors, and eclipse viewers. That active region is emitting strong M-class flares. Visit Spaceweather.com and click on the Daily Sun image in the left-hand column.

Hello, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 29th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read titled 110 Things to See With a Telescope (in paperback and hardcover) is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers.

The world will have moonless nights this week as Luna swings sunward in the pre-dawn sky, and that warrants a tour through Lyra the Harp. I suggest you grab your eclipse viewers and solar telescopes and enjoy the sun’s spots, and I update you about the surprise nova outburst in Ophiuchus. Enjoy the bright planets Venus in evening, and Saturn, Jupiter, and Neptune all night long – and check out the many moon transits on Jupiter this week! Read on for your Skylights!

The Sun is Spotty!

The sun is getting more and more interesting nowadays! There’s a huge group of spots on the sun this weekend. Pull out your eclipse glasses!

The intense fusion reactions inside the sun and the flow of ionized particles (mainly Hydrogen atoms split into their components of one proton and one electron) combine to give the sun an intense magnetic field. Since the sun is a sphere of compressed gases, and not a solid ball like Earth, its rotation is differential. A point on the sun’s equator will circle the star once in 24.47 Earth days, but a point close to its northern or southern pole will take almost 38 days! The sun’s average rotation period of 28 days closely matches our moon’s orbital period – but that’s a mere coincidence of nature.

The differential rotation causes the sun’s global magnetic field to wind up tighter over time. Magnetic fields can’t merge or cross one another. (That’s why it’s difficult to push the same poles of two magnets together.) As the sun’s field tightens up, small regions within it develop tangles of magnetism that prevent the heat beneath them from flowing out of the sun. Those cooler areas are visible from Earth as sunspots. Astronomers formally call them active regions, and number them.

Sunspots can develop, grow, and fade in hours and days – or persist for weeks. Viewed from Earth, they take about two weeks to cross the sun’s disk – allowing us time to view the changes. Scientists have also placed satellites on the far side of the sun to watch the solar hemisphere that we can’t see. That’s because, from time to time, the buildup of energy in those tangles gets violently released as solar flares, and as eruptions of matter into space called coronal mass ejections. Those events, which happen in minutes, cause the auroras at Earth’s polar regions to grow stronger. They also endanger orbiting astronauts and satellites with intense radiation – if Earth happens to be in the line of fire. The flares vary in intensity. They are ranked by class, from weak A-class to extreme M- and X-class. During a flare, the magnetic field lines are snapping and re-connecting into simpler configurations.

For a period of time, more and more spots appear, and more and more violent events occur. Eventually, the sun sheds its excess energy, the magnetic fields smooth out, and the sun settles into a quiet period with no, or very few, sunspots and flares. Over the years, astronomers have been able to view the sun through filters, count the sunspots, and record their number in a log. It turns out that the sun needs about 11 Earth-years to build up and then wind down. Even more interestingly, the polarity of the magnetic field reverses with each sunspot cycle, producing a 22-year period between true cycles. There are lots of online sources showing graphs of the counts, including this page of recent ones and this one. I posted a 400-year-long sunspot count graph on Astrogeo.ca here.

The round disk of the sun we see (through proper filters) is not the sun’s surface. Instead, it’s the radius where its gases cease to be opaque to visible light. (I like the analogy of the visible edge of a cumulus cloud in the sky. An airplane can still fly through the cloud.) This “visual surface” of the sun is called the photosphere. There, the temperature is about 5,500 degrees Celsius, or 5,777 K. That’s hot – but cool enough for non-ionized Hydrogen to survive, temporarily.

When a positively ionized Hydrogen nucleus grabs a passing electron, the atom settles down and emits a photon with a wavelength of 656.3 nanometres. That’s in the red part of the visible spectrum. Astronomers call that light HII (“H-two”) or Hydrogen-alpha light. Solar telescopes are designed to throw away all the other colours in the sun’s bright white light and pass only the H-alpha band to the eyepiece or camera.

The sun was almost completely blank for much of the last three years. People with solar filters for their telescopes were disappointed. Fortunately, the sun still sported occasional solar prominences that were visible in H-alpha telescopes. Prominences are elongated, narrow zones where the local magnetic field is enhanced just enough to lift some plasma off the sun and suspend it – allowing it to cool a little. Prominences look like darkened, curved lines when they’re on the sun’s disk – and as fuzz, flags, trees, pyramids and other shapes when seen in cross-section on the sun’s edge. Some people call them flares – but they aren’t. Prominences last a long time, and only change shape on a timescale of hours.

When the spots are large enough or clumped together, they become visible through eclipse viewers without a telescope! Remember to never look at the sun without using proper solar filters on your eyes and your binoculars or telescopes! Your eyes do not have pain receptors, and will not warn you that they are being permanently damaged. In a future post, I’ll share some tips for safe sun viewing.

If you’ve obtained eclipse glasses at a public sun session, a science shop, or in an astronomy magazine, dig them up and use them on the sun today. Yesterday, I checked the current sun picture on Spaceweather.com to see if any spots were present – and there were! Lots of them! A big curved group called AR2860 is in the sun’s lower southern hemisphere. Several smaller spots are elsewhere. Let me know if you are able to see them.

Outburst of RS Ophiuchi – Update

The outburst, or intense brightening, of the recurrent nova star RS Ophiuchi is still underway. It’s worth trying to see it, and show your kids, because they might be grownups when it next happens!

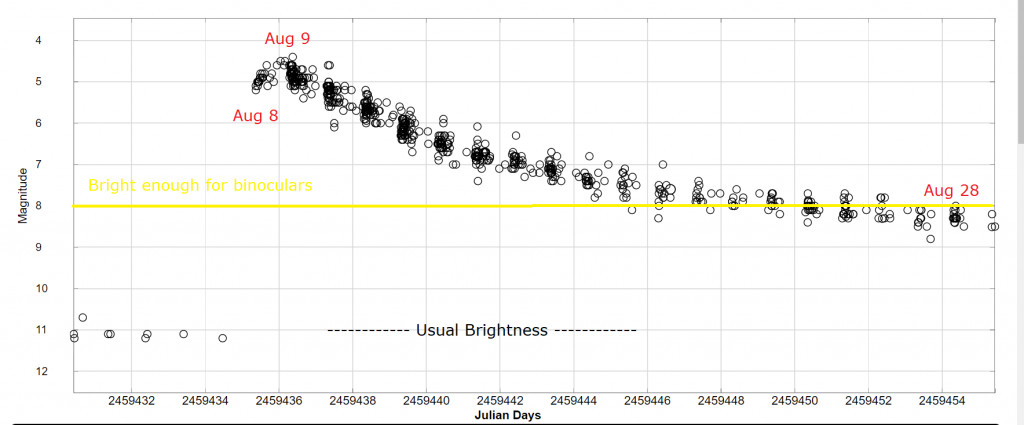

To recap – on August 8, an amateur astronomer in Ireland named Keith Geary observed that a faint 11th magnitude red giant star named RS Ophiuchi had suddenly flared to 400 times brighter – to magnitude 5. That’s bright enough to see without a telescope or binoculars – like a new star or nova – that wasn’t there before! RS Oph (for short) has a habit of doing that. Astronomers have recorded about eight of its outbursts since 1898 – but it hadn’t flared since 2006. I discussed why and showed sky charts here. There’s a great article from Sky & Telescope here.

Other astronomers immediately starting reporting to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) their own estimates of its brightness. It brightened a little more, to magnitude 4.8, on August 9, and then started to fade, as expected, following an exponential curve. In the past, this star has taken 6-8 weeks to return to its normal.

Surprisingly, the rate of RS Oph’s dimming has slowed down (the curve has flattened sooner than expected). Its latest reported brightness of magnitude 8.5 is still just within reach of big binoculars, and will be no problem for any backyard telescope. The star is in the south-southwestern sky at 9 pm local time. It’s a few finger widths above and between the two medium-bright stars v Oph and Mu Oph – or you can search for its reddish dot sitting a slim palm’s width to the left of the middle of the line connecting the bright stars Cebalrai and Sabik.

The Moon

This week will deliver one final dark and moonless period for skywatchers around the world in summer of 2021. Tonight (Sunday) our natural night light will rise shortly before midnight local time and then linger into the morning daytime sky as a faint echo of the night. If you stay up late or rise before dawn, look for the bright little Pleiades star cluster shining a palm’s width above the moon, with the rest of Taurus (the Bull) below it.

The moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 3:13 am EDT or 07:13 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday. At third quarter our natural satellite always appears half-illuminated, on its western side – towards the pre-dawn sun. It rises in the middle of the night and remains visible in the southern sky all morning. The name for this phase reflects the fact that the moon has completed three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon.

For the rest of this week, the moon will wane in phase as its angle from the sun decreases. It will also rise later and later. On Wednesday morning it will depart Taurus for Gemini (the Twins). When its waning crescent rises at about 1 am local time, it will be positioned a finger’s width to the upper left (or 1 degree to the celestial north) of the large open star cluster named the Shoe-Buckle or Messier 35. The two objects will share the view in binoculars and telescopes until the dawn twilight overwhelms the stars. To better see the cluster, which is nearly as wide as the moon, try hiding the moon just outside the upper left edge of your binoculars’ field.

The moon will remain within Gemini until Friday morning. For about an hour before dawn on Saturday morning, the slim crescent moon will shine several finger widths to the left (or 3 degrees to the celestial northeast) of the huge open star cluster in Cancer (the Crab) known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44. The moon and cluster will be close enough to share the field of binoculars, but you’ll see more of the “bees” if you tuck the moon just out of sight on the left. Hours earlier, observers in Europe will see the pair somewhat closer together.

To end this week, the silver sliver of the old moon will shine low in the eastern pre-dawn sky near the heart of Leo (the Lion).

The Planets

At about 8 pm local time this week, the very bright planets Venus and Jupiter will mirror the sky, each sitting about a fist’s diameter above the WSW and ESE horizon, respectively. Extremely bright Venus will emerge from the post-sunset twilight by 8 pm local time then set at about 9 pm. You might need to walk around until you find an open view to the west because Venus will not be much higher than the trees and rooftops. When viewed in a backyard telescope Venus will exhibit a smallish, featureless disk and a football shape because it’s only 73%-illuminated right now. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view.

On the evenings surrounding next Sunday, September 5, the orbital motion of Venus will carry it closely past Virgo’s brightest star, Spica. At closest approach Venus will shine only a thumb’s width above (or 1.5 degrees to the celestial north of) Spica, allowing them to appear together in binoculars and low power telescopes. Venus will pop into view first after sunset – but you’ll need to let the sky darken more to see 100 times fainter Spica with your unaided eyes. Start looking at about 8 pm local time. The pair will be binoculars-close from September 3-8, but ensure that the sun has fully set before using optical aids to view them.

Much fainter Mercury will be shining to Venus’ lower right, just a few finger widths above the western horizon after sunset – but the twilight and clouds or haze will make it tough to see. It will be visible for a short time around 8 pm. Observers who live in the tropics or the Southern Hemisphere will see Mercury (and Venus) easily – higher, and in a dark sky.

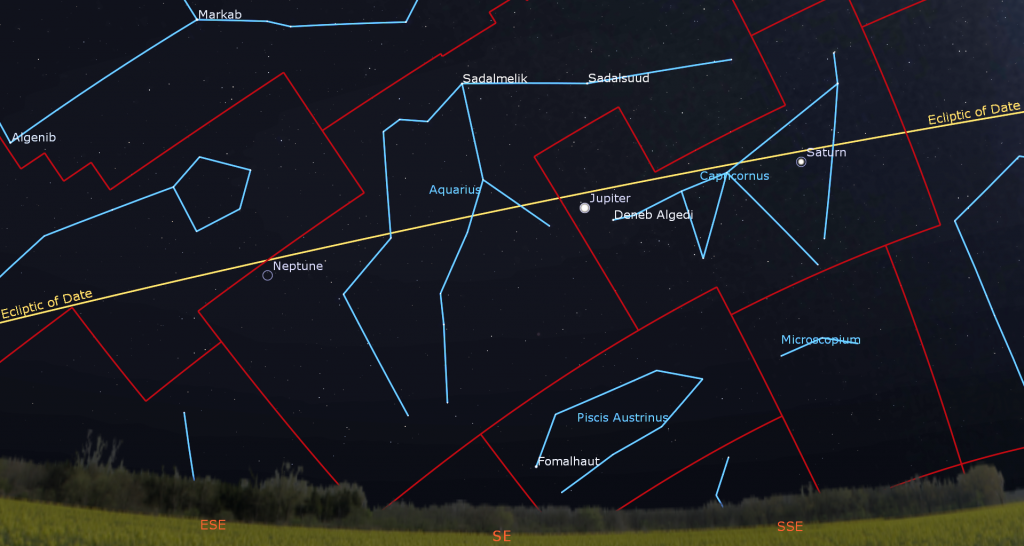

Once the sky darkens a little more, the yellow dot of 16 times fainter Saturn will appear less than two fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right (or 17 ° to the celestial west). They’ll cross the night sky together while riding the stars of the Sea-Goat, Capricornus. The low position of the ecliptic on September evenings is keeping those planets from climbing more than a third of the way up the sky.

From our vantage point on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. During this week, Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the left (celestial east) of of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.)

Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. Much fainter Iapetus can stretch to twelve times the ring width. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other. So it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn (as it is this week), and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn (as it will be during the middle of September). The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas stay within one ring width of Saturn. How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons are always strung like beads along a straight line that passes through the planet and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible crossing Jupiter this evening (Sunday), Tuesday, and next Sunday evening, late on Thursday and Saturday night, and before dawn on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning.

From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Ganymede’s shadow will transit, with the Great Red Spot, on Sunday evening, August 29 from dusk until 10:20 pm EDT, and again next Sunday night from 10:45 pm to 2:15 am EDT. Callisto’s shadow crosses on Wednesday morning from 12:30 am to 4:40 am EDT. Io’s shadow will be visible on Friday morning between 1:40 am and 3:55 am EDT, and on Saturday evening from 8:10 pm to 10:25 pm EDT. Europa’s shadow will cross next Sunday evening from dusk until 9:50 pm EDT.

Dim, blue Neptune is located near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Pisces (the Fishes) – almost three fist diameters to the left (or 27° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. Neptune rises at about 8 pm local time and reaches peak visibility halfway up the southern sky at 1:30 am local time. It will rise and culminate about half an hour earlier each week.

This week Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be observable nearly all night after it rises at about 10 pm local time. It will spend all this year parked below Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram). Uranus is currently surrounded by the moderately bright (5th magnitude) stars Sigma, Omicron, and Pi Arietis – creating a distinctive asterism for anyone viewing Uranus in binoculars.

A Look at Lyra

Once the sky has darkened, tilt your head back and look waaay up – or set out a blanket, gravity chair, or chaise. Point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith – the point of the sky directly above you. During the night, various stars and constellations will pass through that patch of sky as the Earth’s rotation carries them from east to west. While objects occupy that position, they will always appear at their best. That’s because you are looking through the thinnest blanket of intervening air. (Light from objects near the horizon has to pass through as much as ten times more air – making the objects a blurry mess due to increased atmospheric turbulence!)

In early evening during September every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), Hercules, and Draco (the Dragon) occupy the zenith. Let’s tour Lyra, pointing out some objects you can look at with binoculars and small telescopes. In Greek mythology, Lyra was the musical instrument created from a turtle shell by Hermes and later used by Orpheus in his ill-fated attempt to rescue his lost love Eurydice from the underworld. We Canadian astronomers call Lyra the “Tim Hortons Constellation” because it contains both a doughnut and a double-double coffee!

Facing south and looking just to the lower right of the zenith, you’ll easily spot the very bright star Vega, also known as Alpha Lyrae – the brightest star in the constellation. Vega is the fifth brightest star in the entire night sky – partly because it is only about 25 light years away from us, and partly because it is a very hot, luminous star. The name Vega arises from the Arabic “Al Nasr al Waqi”, or the “swooping eagle”. (Pronounce the “W” with a “V” sound.) In traditional star maps, the Lyre was grasped in the talons of a flying eagle.

Vega is moving towards our sun and will continually brighten over time, becoming the brightest star in the night sky a few hundred thousand years from now. Meanwhile, the wobble of the Earth’s axis will also cause Vega to displace Polaris as the northern Pole Star around 14,500 AD. It was previously the pole star around 12,000 BC. This star is a star!

Vega is also the brightest, highest, and most westerly of the three beautiful, blue-white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism. Moving clockwise, Altair is about three fist widths below and to the left (or 34° to the celestial south) of Vega. The star Deneb, slightly dimmer than the other two, completes the large triangle at the upper left. The separation between Deneb and Vega is shorter, only 24°, or 2.5 fist widths.

Chinese culture celebrates a love story in which a Cowherd named Niú Láng (牛郎) is the star Altair. Long ago, the Cowherd and his two children, (β and γ Aquilae, the stars that flank Altair) were separated from their mother Zhī Nǚ (織女) the “Weaving Girl” (Vega) – banishing her to the far side of the river, which is represented by the Milky Way. As the story goes, each year, on the seventh day of the seventh month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, magpies make a bridge across the Milky Way – so that the family can be together again for a single night. Some astronomers believe that the magpies are actually Perseid meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

Look for a medium-dim star about a finger’s width to the left of Vega. A similarly dim star sits about a finger’s width below Vega. Those three stars form a neat little triangle with Vega on the right. Binoculars or a small telescope will reveal that the triangle’s star to the left of Vega, designated Epsilon Lyrae (ε Lyr), is actually a close pair of stars. A really good telescope will reveal that each of the pair of stars is itself a very close together pair! This quadruple star system, or “double-double”, is about 162 light-years from Earth. Even more interesting, each little pair is circling one another, and the two pairs may also be bound gravitationally – in a neat little square dance that takes thousands of years to complete! And that’s your Tim Hortons coffee!

The other corner of our little triangle is the star Zeta Lyrae (ζ Lyr), and it, too can be split into a double star with binoculars. Both are white, and one is slightly brighter than its partner. These stars are about 152 light-years away from us, and they themselves have partners that are too close together to split visually.

Zeta is also the top right star of a narrow, upright parallelogram about two fingers wide and four fingers tall that forms the rest of the constellation – the body of the harp itself. Moving clockwise, the other three stars are Sheliak, Sulafat, and Delta Lyrae. Sheliak, meaning “Harp”, is the brightest of a tight little grouping of stars visible in a telescope. Sheliak is a variable star. It has a close-in, dim partner that orbits the main star so that, every 12.94 days, like clockwork, the brighter star is blocked, and the total brightness we see drops by half (from magnitude 3.5 to 4.4). Astronomers call this an eclipsing binary system.

Next, at the bottom of the parallelogram, sits Sulafat, meaning “Turtle”, and named for the shell forming the body of the Lyre. Sulafat is a hot, blue giant star located 620 light-years away. Similar in colour to Vega, Sulafat is much larger – an old star on its way to becoming an orange giant many years from now.

Finally, at the upper left of the parallelogram is Delta Lyrae (δ Lyr). Sharp eyes and binoculars will easily reveal that this is yet another pair of stars – one blue (upper) and one red (lower). The two are not related – the blue star is several hundred light-years farther away than the red one. They just happen to appear close together along the same line of sight. You can see Sheiak’s changes in brightness yourself! At its peak, Sheliak shines as brightly as Sulafat. At its minimum, it’s as dim as Delta Lyrae. Have a look on any clear night!

Above and between Sulafat and Sheliak sits a gorgeous coloured double star with the dull name of HIP92833 or HR7140. You should be able to make it out with your unaided eyes at any dark sky location. Viewed in a telescope, the star splits into a fantastic yellow and blue pair. A similar, but dimmer pair named HIP92932 sits only 19 arc-minutes to the southeast. That’s about half a pinky finger width to the lower left.

So, where’s our doughnut? Train your telescope midway between Sheliak and Sulafat, and look for the little, dim, grey smoke ring known as the Ring Nebula (also known as Messier 57). This little bubble of gas in space is the remnant of a dead star of a similar mass to our Sun. These common objects are called planetary nebulae because they exhibit a little round disk, like a planet. Finally, using binoculars or a telescope, sweep to the lower left the line that joins Sheliak to Sulafat. At about twice their separation (from Sulafat) is a globular star cluster called Messier 56. It will appear as a dim fuzzy patch – a Timbit!

With a telescope, check out the magnitude 7.5, very red carbon stars T Lyrae and HK Lyrae. They form a triangle two finger widths below Vega – one to the left, the other to the right.

Let me know how your exploration of Lyra goes.

The Eagle and the Dragon

Last week I wrote about the Summer Triangle asterism’s star Altair, the head of the great eagle Aquila, and the northerly constellation of Draco (the Dragon). I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, September 14 with our recommended astronomy and space books. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here. Note: If you registered for the Zoom series last year, you will have received an email asking you to please re-register before Tuesday. (We’re cleaning out older unused registrations to make room for new viewers from libraries across Canada this fall.)

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!