A Waning Moon Gives Early Geminids, and We Tour Pretty Princess Andromeda!

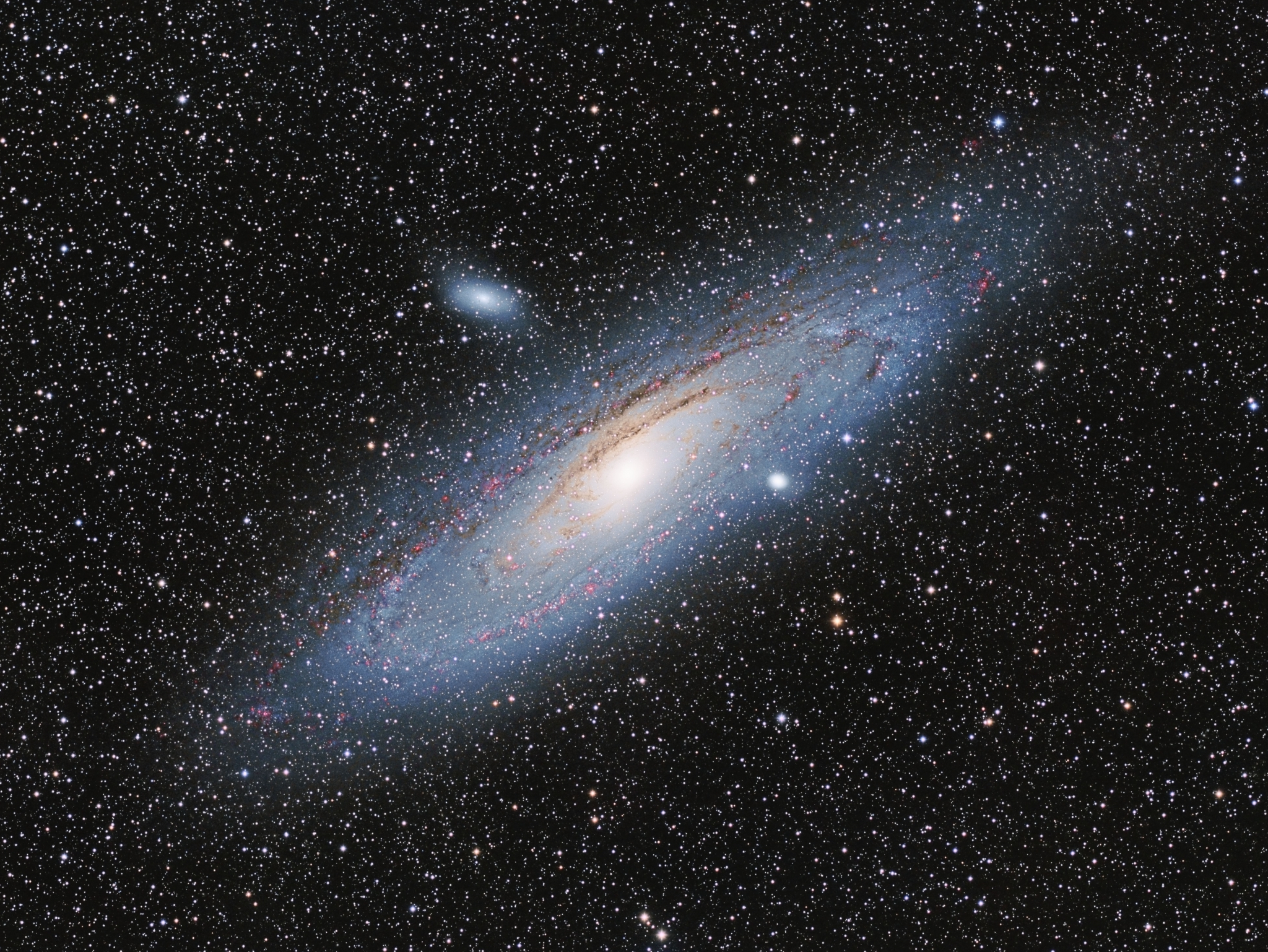

Ron Brecher captured this image of Messier 31, plus Messier 110 and Messier 32 on December 5, 2016. Ron’s original image is and more information are at https://astrodoc.ca/m31/

Hello, Evening Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 29th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

To begin this week, the moon will reach full and a penumbral lunar eclipse – then wane and rise later each day, leaving worldwide evening skies dark by week’s end. That’s a perfect excuse to tour pretty princess Andromeda. The bright planets Jupiter and Saturn continue to move closer together in the western early evening sky, while Mars shines on high and Venus gleams in the east before sunrise. Watch for early Geminids meteors on the coming weekend. Read on for your Skylights!

Meteor Shower News

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, runs from December 4 to 16 annually – so you can begin to watch for the occasional Geminids meteor from Friday onward. The number of meteors will ramp up to a peak before dawn on Saturday, December 14, when up to 120 meteors per hour are possible under dark sky conditions. Then the number will rapidly taper off. Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely coloured, and slower moving than average because they are produced by particles dropped by an asteroid designated 3200 Phaethon.

I’ll tell you more about them next week. In the meantime, my last Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy stream was all about meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

The Moon

Please forgive me for re-stating some of the full moon information I posted last week. At that time I wanted to give everyone a bit of advance notice about the full moon and penumbral lunar eclipse happening overnight tonight (Sunday)!

In the Americas, the moon will be precisely full before dawn on Monday, November 30 at 4:30 am EST, or 9:30 Greenwich Mean Time. Since it’s opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, the full moon rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. If you look closely at the rising moon on Sunday evening, you should be able to tell that it’s not quite full, yet. A thin sliver on its lower left edge will still be dark – making it look less than perfectly round. When the moon rises just after sunset on Monday evening, that missing sliver will have jumped to moon’s opposite, right-hand edge – because the moon’s angle from the sun has changed from less to 180 degrees, to slightly more than 180 degrees.

Sunday night’s moon will sit just above (to the celestial north of) the centre of of Taurus (the Bull). The bright, orange-tinted star Aldebaran, which serves as the bull’s southern eye, will sit below the moon in evening. Binoculars might show you the large open star cluster, known as the Hyades, that forms the rest of Taurus’ triangular face – if you keep the bright moon hidden just above your field of view. Meanwhile, the bright little Pleiades star cluster will be positioned above the moon. By dawn, the rotation of the sky will lift Aldebaran and the Hyades’ stars to the moon’s left.

The November Full Moon, traditionally known as the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Taurus and Aries. Full moons occurring during the winter months climb as high in the sky around midnight as does the summer noonday sun, and cast similar looking shadows from the trees and structures in your backyard.

Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this one Mnidoons Giizisoonhg, the “Little Spirit Moon”, a time of healing. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Kaskatinowipisim, the “Freeze Up Moon”, when the lakes and rivers start to freeze. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon. With this full moon occurring on the boundary between modern calendar months, which were not employed by indigenous groups, it might be more appropriate to use their December moon names. But I’ll wait until next month to share those.

The moon’s orbital motion while it’s full will carry through Earth’s circular outer shadow, producing a penumbral lunar eclipse that will be visible in its entirety across most of North and Central America, and northern Asia. The moon will first contact the Earth’s outer shadow at 2:32 am EST, or 07:32 GMT. At greatest eclipse at 4:44 am EST, or 09:44 GMT, approximately 83% of the moon’s disk will be within the Earth’s southern penumbral shadow. At that time, the moon will be sitting rather low in the western sky for observers in the Eastern Time zone.

Penumbral eclipses aren’t very obvious, at all – but they are perfectly safe to look at without eye protection. The subtle darkening of the moon’s right-hand (northern) limb will be noticeable only within about 30 minutes of greatest eclipse. The eclipse will end at 6:53 am EST, or 11:53 GMT. In the Eastern Time zone, the moon will be close to setting at that time. For observers in more westerly time zones, the eclipsed moon will sit higher in the western sky. South America and northern Europe will only see the early stages of the eclipse, while Australia, Southeast Asia, China, and parts of Russia will only see the latter stages. I posted a diagram of the event here. I won’t be getting out of bed for this one – but do let me know if you see it!

For the rest of this week, the moon will rise later each night and wane in phase – delivering darker evening skies around the world by the coming weekend. On Monday and Tuesday night, the moon will complete its trip through Taurus. By Monday morning, the moon will cross into Gemini (the Twins).

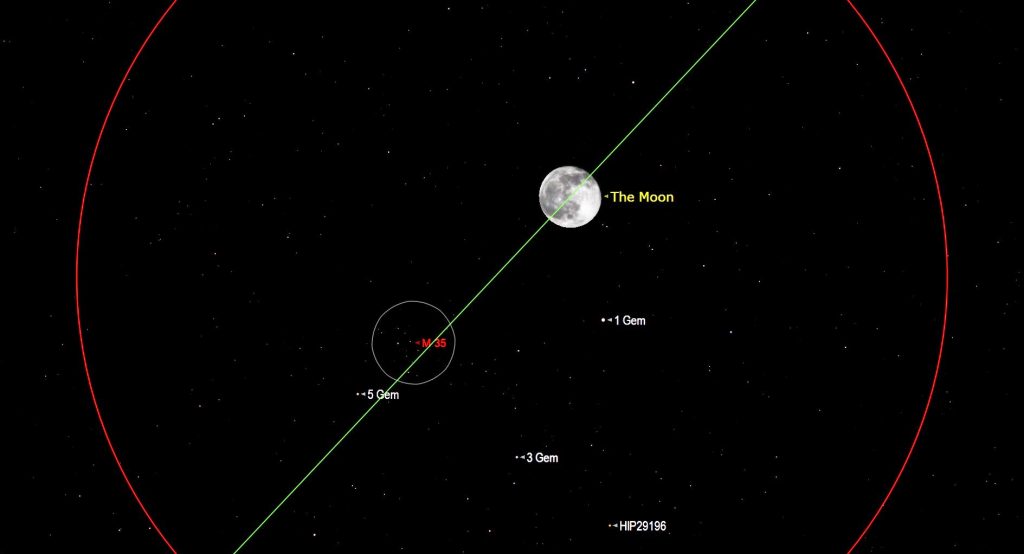

During the wee hours of Monday morning, observers in most of North America can see the orbital motion of the moon carry it in front of a large open star cluster known as Messier 35, or the Shoe-Buckle Cluster. While the moon climbs the eastern sky during Tuesday evening, it will be slowly approaching the cluster from the upper right, or celestial west. To best see Messier 35’s stars at that time, wait until they are higher after mid-evening, and then hide the bright moon beyond the upper right edge of your binoculars. The moon will obscure all or part of the cluster for about 2 hours centered on 3:40 am EST (or 8:40 GMT), and then it will depart from the cluster’s eastern edge while the moon and cluster descend in the western sky. The moon’s motion and the rotation of the sky will serve to put the cluster to the moon’s lower right before dawn.

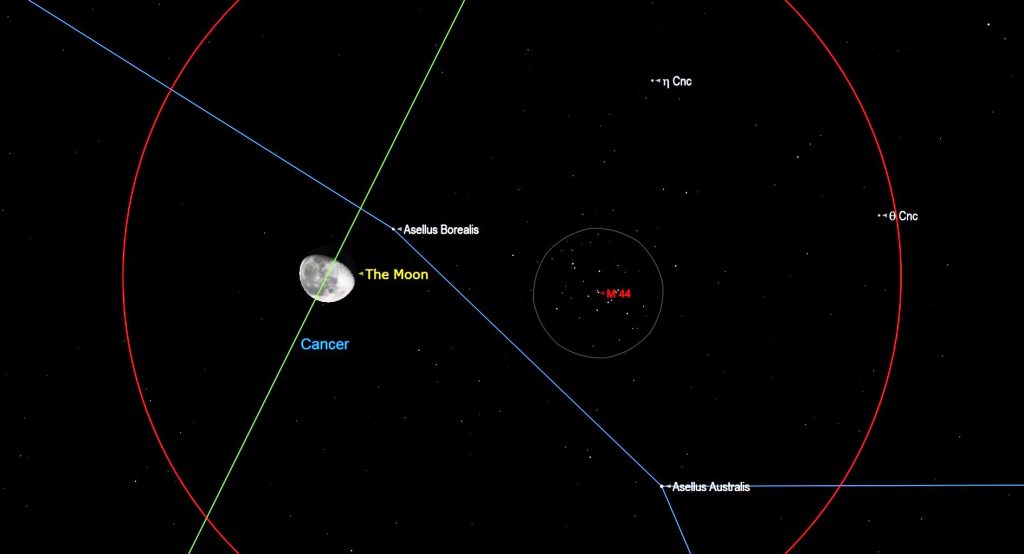

The moon will use Wednesday and Thursday to cross Gemini, and then it will slide into Cancer (the Crab) on Friday night. When the waning gibbous moon rises in the eastern sky in late evening on Friday, it will positioned only two finger widths to the left (or 2 degrees to the celestial north) of the large open star cluster known as the Beehive Cluster, or Messier 44, in Cancer. The cluster, which contains at least 1000 stars, extends for two full moon diameters across the sky. The moon and the cluster will fit together in the field of view of binoculars. To best see the cluster’s stars, hide the bright moon just outside the left edge of your binoculars’ field of view. During the rest of the night the moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry it farther from the Beehive and the rotation of the sky will drop the cluster to the moon’s lower right.

The moon will end the week rising in late evening among the stars of Leo (the Lion).

The Planets

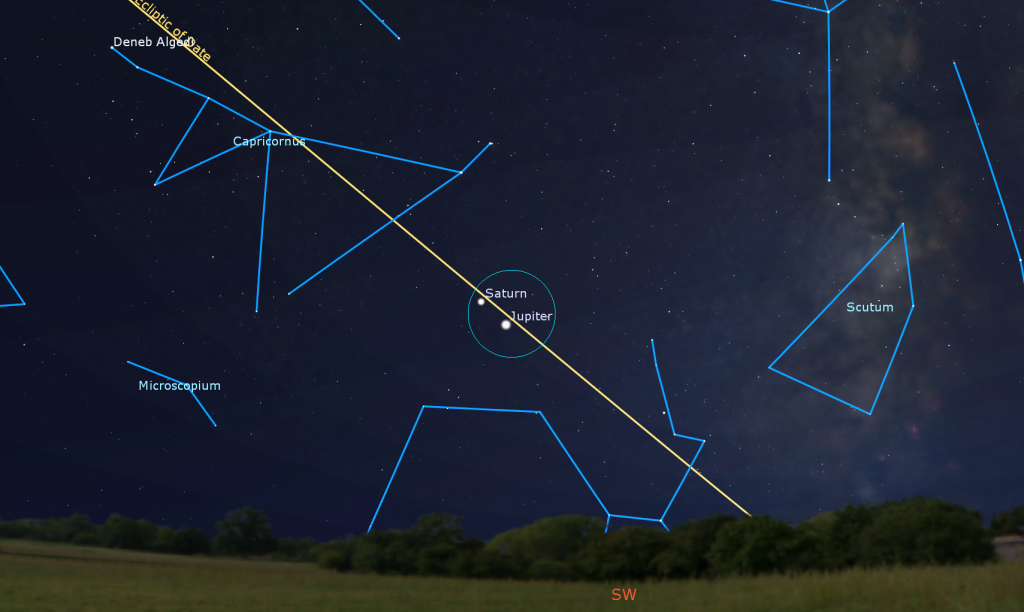

Have you noticed that Jupiter is getting closer to Saturn? Being closer to the sun, Jupiter is moving eastward faster than Saturn. It’ll catch up and then pass Saturn on December 21, when they’ll look like a single, bright ”Solstice Star” shining in the west! In the meantime, watch their separation decrease every week. As the sky begins to darken each night, look for very bright, white Jupiter shining in the lower part of the southwestern sky. Yellowish Saturn is smaller in size and farther from us than Jupiter. That makes it about 12 times dimmer than Jupiter – so it doesn’t become visible until the sky gets darker. This week, the yellowish ringed planet will sit less than two finger widths to Jupiter’s upper left (or about 2 degrees to the celestial east).

Our season of clear telescope views of those two planets is ending. After 6 pm in your local time zone, they will be getting very low in the southwestern sky, and shining through a much thicker blanket of Earth’s atmosphere. You might even see them twinkle a little bit before they set! Good binoculars should still show you the four large Jupiter moons that Galileo Galilei discovered in January, 1610. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, they dance around the planet from night to night – although one or more can be hidden by Jupiter at any given time.

Saturn is a spectacular sight. Any backyard telescope will show you Saturn’s rings. Your telescope should also reveal several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to above the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.)

Back in June and July, when they were moving retrograde westward, Jupiter and Saturn passed close to a globular star cluster named Messier 75 (or M75). Now that the two planets have resumed normal eastward motion, they are going to pass that cluster again. This week, in binoculars or telescopes, look for a faint fuzzy patch located about two finger widths to the left (or 2 degrees to the celestial southeast) of Jupiter. Try to see the globular cluster at about 6 pm local time – when it’s higher, and the sky has darkened fully. Use a low magnification eyepiece in your telescope, and scan around, keeping Saturn near the edge of the circular field of view. Messier 75 will appear at the same time as Saturn – but where it sits will depend on the way your telescope flips and/or inverts the view.

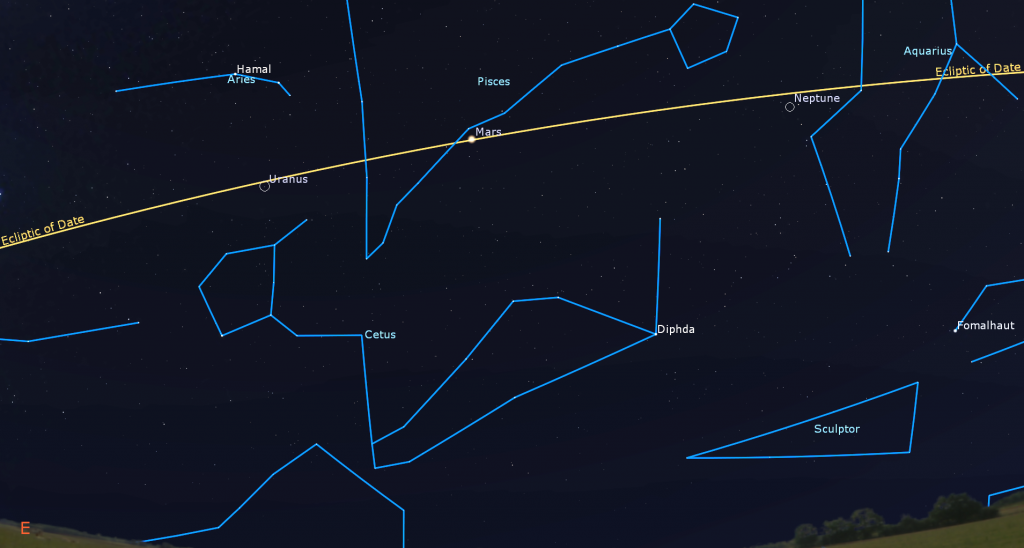

Mars is still a wonderful evening and late-night target! This week, the bright, reddish-tinted planet will already be shining in the lower part of the southeastern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point – and best viewing position, a bit more than half-way up the southern sky – at about 8:30 pm local time. Then it will set in the west well before sunrise. The planet is now moving slowly eastward toward the V-shaped stars of Pisces (the Fishes) on its left. Mars will be rapidly fading in brightness and size from this point forward – so view it at the earliest opportunity.

Blue-green Uranus is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. For context, that region of the sky is two fist diameters to the left (or 20° to the celestial east) of Mars. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is usually within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – especially once bright moon leaves the evening sky.

Deep blue Neptune is located about 2.9 fist diameters to the right (celestial west) of Mars – among the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The dim, magnitude 7.86 planet is sitting about two finger widths to the left (or 2 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, dim and distant planet will already be in the lower southeastern sky after dusk. Then it will climb higher until just 7:30 pm local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s almost halfway up the southern sky.

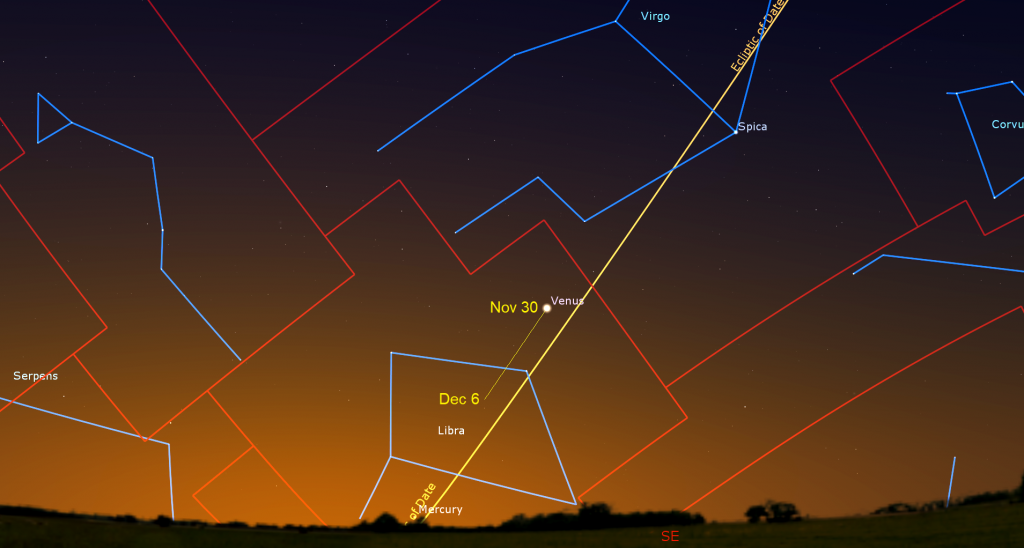

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now. It will rise at about 5:15 am local time this week, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a slightly less than round shape. This week, the planet will be traveling down (or celestial eastward) – through the stars of Libra (the Scales). Venus is shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will allow it to shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until later in December!

Princess Andromeda’s Treasure

During the fall, I began to showcase the constellations involved in the Greek mythology story of Perseus and Andromeda. In this September Skylights post, I toured Andromeda’s father Cepheus (the King), and in this October Skylights, I highlighted Pegasus (the Flying Horse). This week, I’ll tell you more about the princess herself. We’ll tour the other related constellations in future posts.

Once upon a time, Andromeda was the beautiful daughter of Queen Cassiopeia and King Cepheus of Ancient Ethiopia. Through no fault of her own, the princess became the centre of a hair-raising story. After her mother angered the Nerieds (Sea Nymphs) by boasting of Andromeda’s unrivaled beauty, the god of the sea Poseidon (aka Neptune) sent Cetus, the Sea-monster to ravage Ethiopia’s coast. An oracle told King Cepheus that his only solution was to sacrifice Andromeda to Cetus. So she was chained to rocks by the sea-shore. Just as Cetus was about to take Andromeda, the hero Perseus happened to be flying by on his weinged sandals. She must have been beautiful indeed, because he instantly fell in love with her, slew the beast, and cut her free from her chains. One drop of the beast’s blood mixed with the sea foam, and Pegasus the flying horse was born. After more adventures, including one where Perseus accidently killed his evil grandfather to fulfill a prophecy, the couple sailed to Argonis, where they raised a family of many children. Hercules is descended from them.

Andromeda is one of the original classical constellations, and is 19th largest by area (out of 88). Also known as the Chained Lady, she is depicted as laying prone with her body and legs extending to the east (left) formed by two chains of stars that diverge towards her feet. A row of dimmer stars that extends upwards toward the Milky Way represents her chains. A number of ancient cultures saw a woman’s figure in those stars. The ancient Chinese also envisaged legs – but used a different arrangement of stars. You can view a nice portrait of her here. (Parental discretion advised.)

A large part of Andromeda’s territory occupies the sky above Pegasus and below Cassiopeia. While modern star charts don’t draw lines between any of the modestly bright stars in that area, classical depictions of the princess use those stars as the rocky crag she’s chained to.

Andromeda is visible throughout the fall and winter, but in early December she is almost directly overhead, high in the southern sky, during mid-evening. She is connected to Pegasus on her western (right) side. Her brightest star, named Alpheratz “the Horse’s Shoulder”, marks her head, and is also serves as “third base” of Pegasus’ great square. Pisces (the Fishes) swim below her, with Triangulum (the Triangle) just to the left (east) under her feet. Her mother Cassiopeia is above her, and Perseus lies off to the east. He’s under her feet, but positioned to her upper left in the sky.

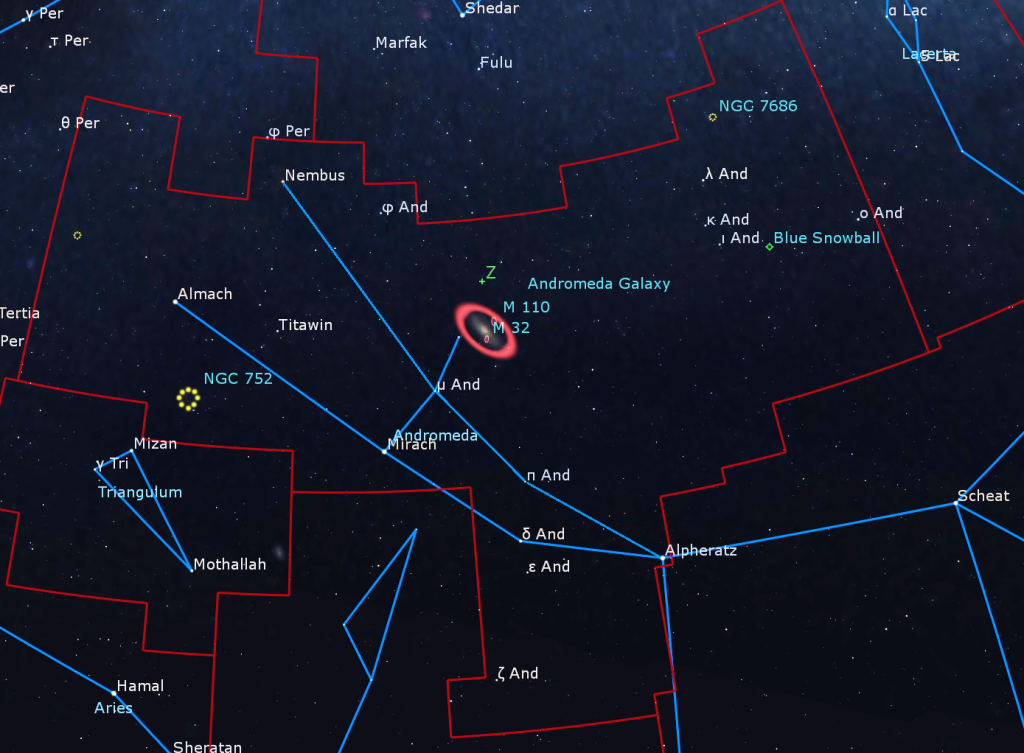

Let’s tour the best of Andromeda, starting at bright Alpheratz. It’s a hot, blue-white supergiant star located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal Mercury. To see the rest of her, look for two slightly bent, roughly horizontal, lines of three modest stars each extending off to the northeast (left). The two lines are longer than the great square’s diagonal, and the lower stars are brighter than the upper set. They diverge as you move away from Alpheratz, the way her gown would spread out towards her feet.

Tracing the lower line of three stars from Alpheratz, reddish Delta Andromedae (or δ And) sits roughly a palm’s width left of Alpheratz. The next star, another palm width along, is a bright reddish star called Mirach. This is a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years from Earth. It produces 1,900 times more light than our sun! Mirach happens to have a 10 million light-years-distant elliptical galaxy close above it called Mirach’s Ghost (or NGC 404) – but you’ll need a large telescope to see its fuzzy little patch. (Make note of Mirach – we’ll return to it later.)

Continuing left by a fist’s diameter, we reach one of Andromeda’s feet – the bright double star Almach “desert lynx”. Almach’s beautiful golden and sapphire duo easily is seen in a small telescope. The two stars differ in both brightness and colour.

About midway between Mirach and Almach, and a thumb’s width above the line connecting them, sits a medium-bright magnitude 4.1 star named Titawin (or Upsilon Andromedae). The main star is a binary system with a faint, orbiting companion. And it hosts four Jupiter-sized exoplanets discovered between 1996 and 2010! Three of the planets have been named after Andalusian scientists: Saffar, Samh, and Majriti. The magnitude 3.55 star that marks Andromeda’s higher foot is an orange-tinted star named Nembus.

Now, head back to Mirach and follow Andromeda’s chain upwards. Sitting about four finger widths above Mirach is a dimmer white star designated Mu Andromedae (or μ And). (It’s actually the centre star of Andromeda’s higher leg.) A few finger widths above that star sits another even dimmer star named Nu Andromedae (or v And). Look just above that one for a large fuzzy patch. That’s Messier 31 (or M31 for short), better known as the Andromeda Galaxy – one of the sky’s best sights! This massive twin to our Milky Way galaxy spans six full moon diameters across the sky. It has a bright core and dim oval halo that is oriented east-west (left-right). It’s easy to see with binoculars. Using a good sized telescope, more is revealed – including two smaller galaxies sitting just above and below it. One of these is closer than M31 – the other is farther.

Under dark skies, you should be able to glimpse the galaxy using unaided eyes only. At about 2.5 million light years away, it’s one of the farthest objects visible to unaided human eyes! We’re going to collide with it in about 5 billion years, but that’s another story!

Andromeda contains two more interesting deep sky objects. A large, loose open star cluster named NGC 752 is located below and between Almach and Mirach. Look for a tight little triangle of warm-tinted stars in its core. On the opposite end of the constellation, about 1.5 fist diameters above Alpheratz is the Blue Snowball (or NGC 7662). This magnitude 8.3 planetary nebula, the decaying corpse of a star of similar mass to our own sun, is fairly easy to see in backyard telescopes – but it’s tiny. In your telescope, look for a non-twinkling dot with a faint blue-green colour.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, December 1. We’re going to look closely at everyone’s favorite constellation – Orion! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!