An Evening Moon for Viewing, a Christmas Constellation and Asterism, and All Planets After Sunset!

Merry Christmas to those who celebrate! This wonderful object, known as the Christmas Tree Cluster or NGC 2264, is located in the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn), which occupies the winter sky between Orion and Gemini. The red glows are hydrogen gas being energized by the clump of hot, young stars recently born in the centre. Blues arise from starlight reflecting off surrounding dust, and the dark patches are more dust that is obscuring light behind it. The image by Rolf Geissinger of southern Germany, was NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day for April 10, 2012. It spans about one finger’s width of the sky.

Hello, end of 2022 Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 25th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will shine in evening worldwide this week, joining all the bright planets in the sky at once after sunset. I highlight some sights to see on the moon and share some yuletide celestial sights. Read on for your Skylights!

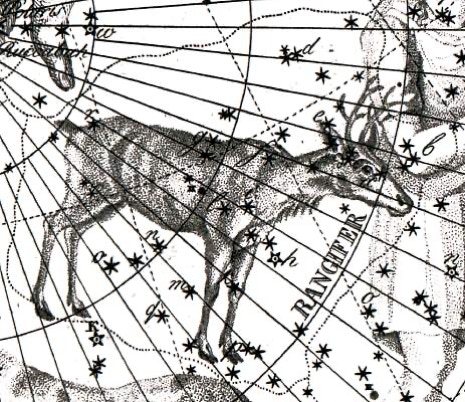

A Christmas Constellation – Rangifer (the Reindeer)!

According to astronomer Ian Ridpath, French astronomer Pierre-Charles Le Monnier (1715–99), in a star chart published in his 1743 book La Théorie des Comètes, created a faint, far-northern constellation close to the north celestial pole between Cepheus (the King) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). When illustrating the track of the Comet of 1742 through the north polar region of the sky, Le Monnier envisioned a reindeer on the comet’s course!

Labelled in various old charts as Rangifer and as Tarandus, he connected up some of the modest, magnitude 4 and 5 stars sitting between the “W” of Cassiopeia and Polaris. You have probably not heard of this star pattern because it is not one of the IAU’s official 88 constellations. Ian’s story about the reindeer is here. I think I’ll have to look for the critter on the next clear night!

The Christmas Goose

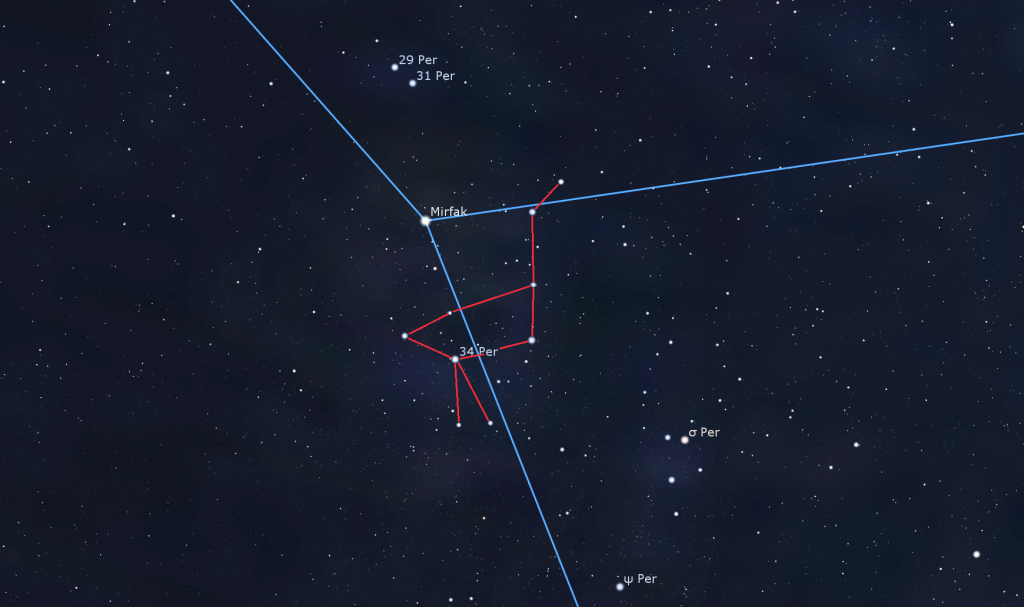

The brightest star in Perseus (the Hero) is Mirfak or Alpha Persei (α Per). On the evenings surrounding Christmas every year, Perseus can be found climbing the eastern sky above the very bright star Capella and below the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen). Grab your binoculars! Mirfak’s golden light sparkles at the upper left (northwestern) edge of a large and loosely scattered cluster of about 100 hot, bright, blue-white B and A-class stars known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group, the Perseus OB Association, and Melotte 20. Those stars are siblings of Mirfak – born from the same molecular hydrogen cloud about 41 million years ago – and now travelling through the galaxy together with Mirfak. The open star cluster, which is sprinkled across 3 degrees of the sky, can be seen with unaided eyes, and looks wonderful in binoculars.

In his book Binoculars Highlights, astronomer Gary Seronik suggested that the brightest stars in Mirfak’s cluster resemble a goose, so those stars are now nick-named the christmas Goose asterism.

The Moon

The moon will be perfectly placed for evening viewing worldwide this week. Having risen in the afternoon daytime sky, it will be sweeping east through the early evening stars and waxing fuller as it flees the sun – letting even the younger astronomers enjoy views of it around dinner time.

Use your binoculars or telescope to view the terrain along the pole-to-pole lunar terminator that divides its dark and lit hemispheres. The terminator is the zone where the sun is rising on the moon. Sunlight arriving there is nearly horizontal, producing severe shadows to the lunar west of every bump, ridge, mountain, and crater rim. With no atmosphere on the moon to scatter light, the edges of those shadows are sharp and the interiors are inky black, producing spectacular vistas in binoculars and in any size of telescope.

During a romantic date on Earth, you can pause your dinner to watch the sun set. It only takes a few minutes. On the moon, the restaurants have no atmosphere, and the sun takes hours to rise or set. In as little as a few hours you can note differences in the way lunar features are lit and shadowed. Watch craters fill with light, initially at their central peaks. Or, note whether the shadows in partially illuminated craters are smoothly curved (indicating a bowl-shaped depression) or have straight sections (showing that the crater resembles a pie-pan).

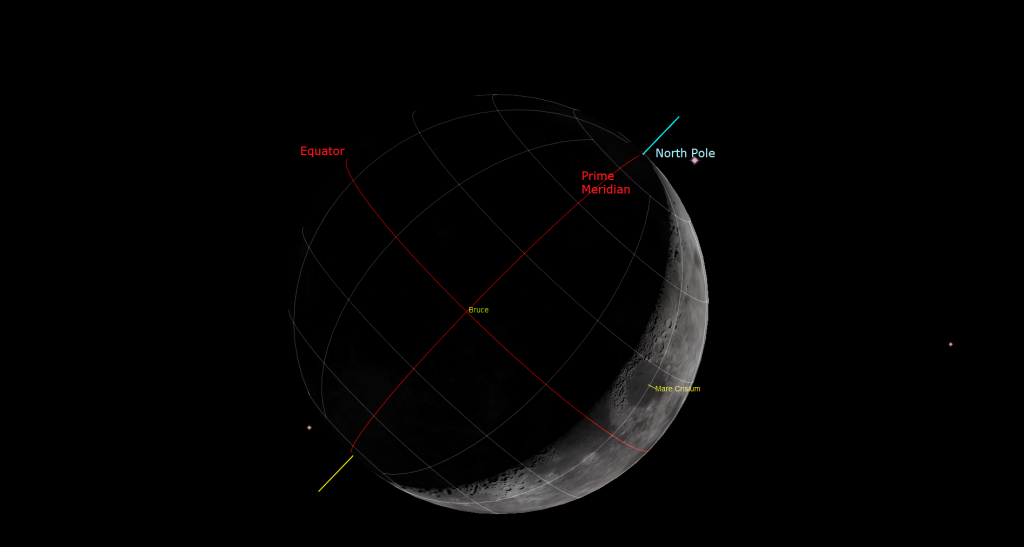

Due to the moon’s 1.5° axial tilt and its orbital inclination (or tilt) and ellipticity (or out-of-roundness), the moon nods up-and-down by up to 7° and twists left-to-right up by to 8° while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth. Over time, this lunar libration effect lets us see an extra 9% of the moon’s total surface without having to leave the Earth! Lunar features that are normally smeared along the moon’s edge or completely hidden can rotate into clearer view for a few nights. The librated sector of the moon’s limb migrates clockwise around the moon over a lunar month – but librated features can only be observed if their sector happens to be bathed in sunlight at the same time.

For the first few nights of this week, you can see libration’s effect on the moon at a glance by watching Mare Crisium “the Sea of Crises”. That’s the isolated, dark, round feature located near the lower right-hand (eastern) edge of the moon, just north of the moon’s equator. Mare Crisium becomes fully illuminated starting about four days after new moon each month. That will be Monday night this week. Whenever the waxing crescent moon is descending in the western sky after sunset, Mare Crisium is the most noticeable dark blob within the illuminated crescent. Because the moon’s northeastern edge will be rotated toward Earth during the next few days, Mare Crisium will sit nearer the centre of the moon’s crescent and extra far from the moon’s edge.

Tonight (Sunday) the moon’s slender crescent will grace the southwestern sky after sunset – perched between the yellow dot of Saturn to its upper left and the planets Venus and Mercury gathered to its lower right. You might see Earthshine, too. Sometimes called the Ashen Glow or the Old Moon in the New Moon’s Arms, the phenomenon is visible within a day or two of new moon, when sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon slightly brightens the unlit portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. As the sky darkens the inner planets will sink out of sight and the modest stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will appear above the moon.

After dusk on Monday evening, the slightly thicker moon will shine prettily beside Saturn in the southwestern sky, with the tail stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), magnitude 2.85 Deneb Algedi and half-as-bright Nashira, twinkling between them. The yellowish ringed planet will be positioned several finger widths to the upper right (or 5 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the moon – close enough for the moon, the planet and the two stars to share the view in binoculars. By the time the group drops below the west-southwestern horizon after 8 pm local time, the moon will have been rotated to Saturn’s left.

The moon will spend Tuesday and Wednesday crossing the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). On Wednesday evening, the moon will shine near very bright Jupiter and the faint speck of distant Neptune. Magnitude -2.39 Jupiter will be positioned a generous palm’s width to the moon’s upper left, or approximately 8 degrees to the celestial northeast, while Neptune will be located several degrees to the moon’s upper right (celestial north). The 38%-illuminated moon’s light will making seeing magnitude 7.9 Neptune harder – but good binoculars and backyard telescopes can reveal the blue planet – if you hide the moon outside of your field of view.

On Thursday night, the moon will hop to Jupiter’s upper left (or celestial east). They’ll still be close enough to share binoculars after dusk, but those viewing them later, or from farther west, will see them more widely separated. As the moon and Jupiter sink towards the horizon in late evening, the diurnal rotation of the sky will lift the moon above the planet. Thursday’s moon will be half-illuminated, on its eastward side – towards the sun. That’s because the moon will complete the first quarter of its monthly journey around Earth at 01:20 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday, December 30, which translates to 8:20 pm EST and 5:20 pm PST on Thursday, December 29. The straight line of the terminator at first (and third) quarter told ancient astronomers that the moon was a round ball.

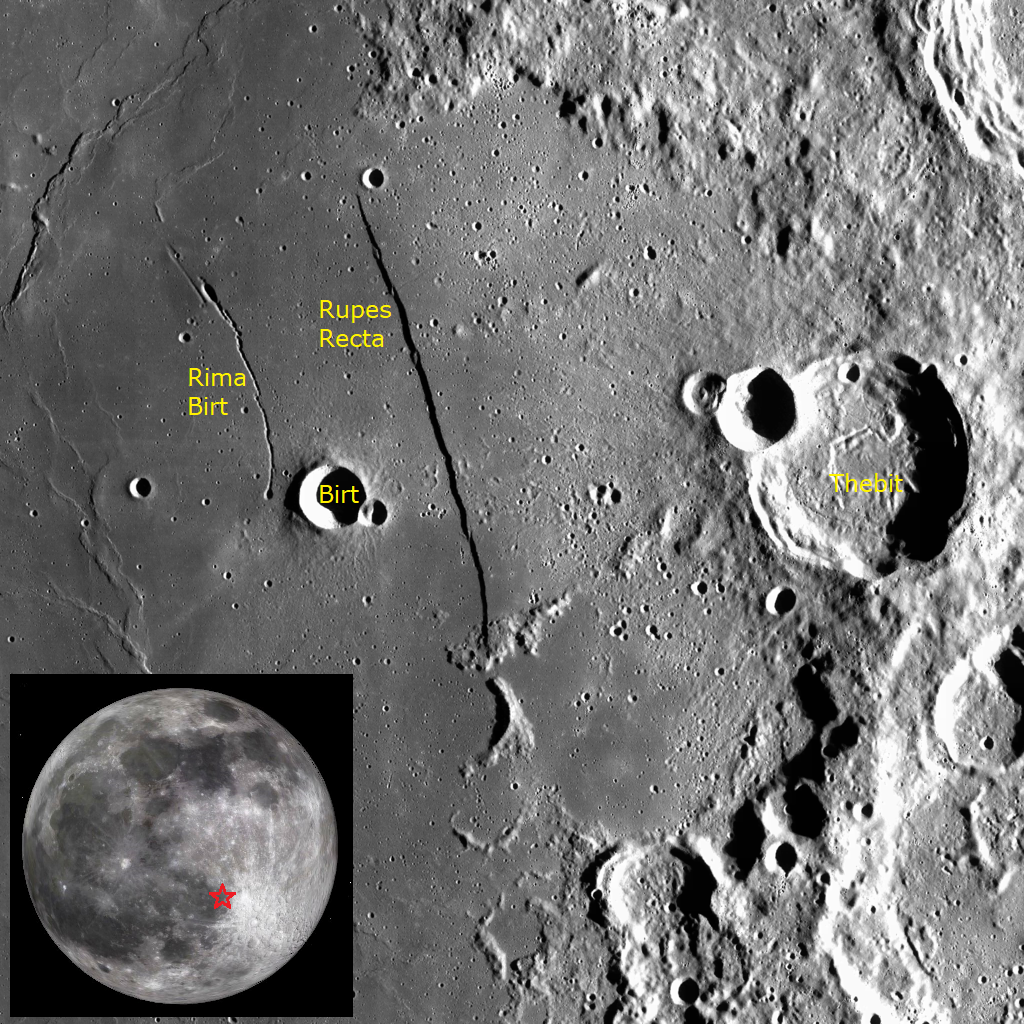

The increasingly gibbous moon will swim along the crooked boundary between Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale) until Saturday. On Saturday night, the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium, the Sea of Clouds. That’s the dark patch sitting in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The wall, which is very easy to see in good binoculars and backyard telescopes, is located above the very bright crater Tycho.

To kick off 2023, on Sunday, January 1, the waxing gibbous moon will rise after mid-day and then linger into the night sky until well beyond midnight amidst the stars of Aries (the Ram). For observers in the Americas, the moon will have just completed an occultation of the magnitude 5.7 planet Uranus. Once the sky darkens in the Eastern Time zone, look for Uranus shining less than a lunar diameter to the moon’s right (or celestial west), allowing the moon and the planet to share the field of view in binoculars and backyard telescopes. In more westerly time zones, Uranus will be 3-4 lunar diameters from the moon. Observers in the Canadian Maritimes and eastward across Greenland, Iceland, most of northern Europe, and most of northern and western Russia can observe the occultation starting around 21:00 GMT.

The Planets

For most of this week, observers with an unobstructed, cloud-free sky to the southwest at dusk can see the moon and every bright planet in the sky at the same time! That’s because the inner planets Mercury and Venus will be shining just above the southwestern horizon after sunset, while the rest of the gang will make their stately way across the celestial stage during the night. Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus will form a 107 degrees-long arc across the sky, tracing out the plane of our solar system. Uranus, Neptune, and a couple of major asteroids will be strung between them.

Tonight (Sunday) Venus will be positioned just a few finger widths to 41 times less dazzling Mercury’s lower right (or 3.3° to the celestial west). Be sure to wait until the sun has completely disappeared before searching for them in binoculars. Venus will show a nearly complete disk in telescopes. It is swinging away from the sun and climbing higher each evening. We’ll enjoy views of it all winter – but Mercury will be descending sunward. By about Thursday or Friday, only observers living at southerly latitudes will be able to see Mercury easily. Once it’s gone, our bright planet party will be missing a member. On Wednesday and Thursday night, Mercury will pass only a thumb’s width to the right (celestial north) of Venus – cozy enough for them to share the view in your telescope.

Don’t fret if you missed Mercury. More opportunities will return soon. In the meantime, the creamy-coloured dot of Saturn will become visible in the lower part of the southwestern sky after about 5:30 pm local time. Take a look at magnitude 0.8 Saturn as soon as you can find it in your telescope because it will look less crisp as it drops into thicker air during mid-evening. Saturn will set at about 8:30 pm local time. As I mentioned in the previous section, on Monday the moon will join Saturn near the medium-bright tail stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Over the next couple of weeks, you’ll be able to use binoculars or your sharp eyesight to see Saturn’s easterly prograde motion shift the planet past them. I plotted Saturn’s long-term path here.

On a night with steady air, quality 10×42 binoculars (and larger) should show Saturn and its rings as a tiny oval. Even a small telescope can show the planet’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings. See if you can make out the Cassini Division, a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring (named B) from its bright outer ring (named A). Any telescope should show that a segment of Saturn’s rings adjacent to the eastern limb of the planet is in shadow. That dark wedge is getting a little smaller every night. Where it sits will depend on how your telescope flips the view.

A small telescope can also pick up several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. (In contrast with Saturn, Jupiter’s axis is only tilted by 3°, so Jupiter’s moons show in a line running through that planet’s equator.)

Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the rings’ width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (or celestial northwest) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the left (or celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Extremely bright, magnitude -2.5 planet Jupiter, which will look about 20 times brighter than Saturn, will become visible in the south around 5:30 pm local time. Jupiter will look best in a telescope when it climbs highest (or culminates) due south around 6 pm, and then it will set in the west at midnight.

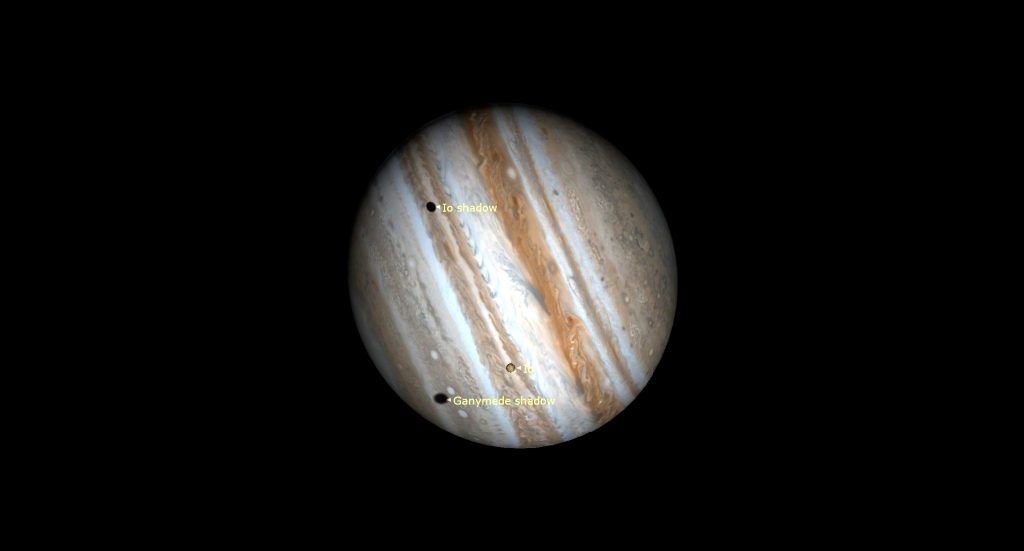

Your binoculars should be able to show you Jupiter as a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. The moons’ arrangement varies each night. On Friday night all four moons will form a short line to the west of Jupiter!

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Thursday and Saturday, and late on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Monday evening, December 26 the small shadow of Io will cross the equator of the planet, from 4:28 pm to 6:35 pm EST. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone. On Friday evening, December 30, sky-watchers located in eastern Asia, Southeast Asia, and Australia / New Zealand can watch two shadows crossing the southern hemisphere of Jupiter at the same time – for about 45 minutes. At 7:27 pm Japan Standard Time or 10:27 GMT, the small shadow of Io will join the larger shadow of Ganymede, which began its own crossing of the planet 90 minutes earlier. Ganymede’s shadow will leave Jupiter at 8:15 pm JST or 11:15 GMT, leaving Io’s shadow to continue on alone until 9:34 pm JST (or 12:34 GMT).

In mid-evening this week, magnitude 7.9 Neptune will be located a generous palm’s width to the lower right (or 7.7° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter, about two-thirds of the way towards the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii. Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.3 arc-seconds (20 times smaller than Jupiter’s). Try to view Neptune while it is highest, around 5:30 pm. The large asteroids designated (4) Vesta and (3) Juno are currently following Jupiter. They are on either side of the eastern knee star of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), named Psi1 Aquarii.

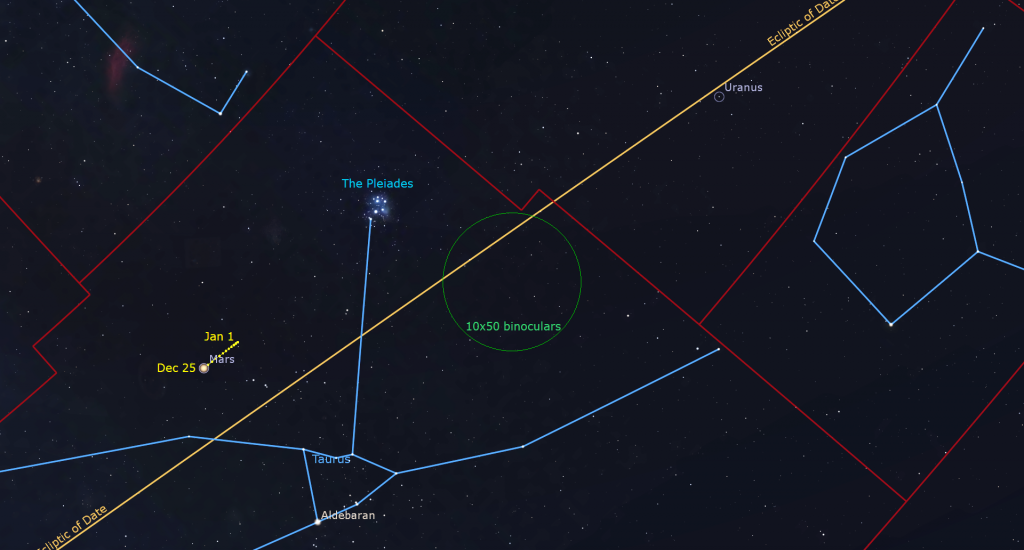

Mars, the red caboose of the celestial train, will continue to be visible all night long. Although it has already started to diminish in brightness after the December 7-8 opposition night, its bright, magnitude -1.5 reddish dot will catch your eye in the eastern sky after dusk. It will climb very high in the south around 10:30 pm local time, then descend westward. Early risers can spot Mars above the western horizon before sunrise. Mars will be positioned above the very bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks Taurus the bull’s eye, and to the lower left of the Pleiades star cluster, which is the prominent little clump of stars above Aldebaran. Until mid-January, Mars will travel towards the Pleiades.

In backyard telescopes this week, Mars will show an apparent disk diameter of 15 arc-seconds (Jupiter’s disk spans about 42 arc-seconds and the full moon is 1,800 arc-seconds wide). Mars’ Earth-facing hemisphere this week will display its bright northern polar cap – visible as a small bright spot along the planet’s edge, and some dark regions. To identify them, you can use a terrific Mars mapping tool created by Ade Ashford at http://www.nightskies.net/skyguide/mars/mars.html. Use the drop-down menu to select from two views of Mars, labelled or not. Mars takes about 20 minutes longer than Earth to rotate once fully on its axis. So viewing the planet at the same time on consecutive nights will show roughly the same view of it – but with its surface markings shifted by about 5°. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

The distant blue-green planet Uranus is located about 35% of the way from Mars towards Jupiter, and about 1.5 fist widths to the upper right (or 15° to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will already be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the middle part of the eastern sky, after dusk this week. It will climb to its highest point in the southern sky just before 9 pm local time.

A Peek at Perseus

Fall and winter evenings host the constellations involved in the Greek mythology story of Perseus (the Hero) and Andromeda (the Princess). Last month I told part of Andromeda’s story and toured her stars and deep sky objects here. Two weeks ago, I described her mother, Queen Cassiopeia’s constellation here, and last week I looked at the Hero Perseus here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Most organizations are taking a well-earned break.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 17 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll select a fun topic in astronomy, and we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!