An Eye on Jupiter, Lunar LOVE, Maximum Mercury, Nearest Neptune, and Galaxy Gazing!

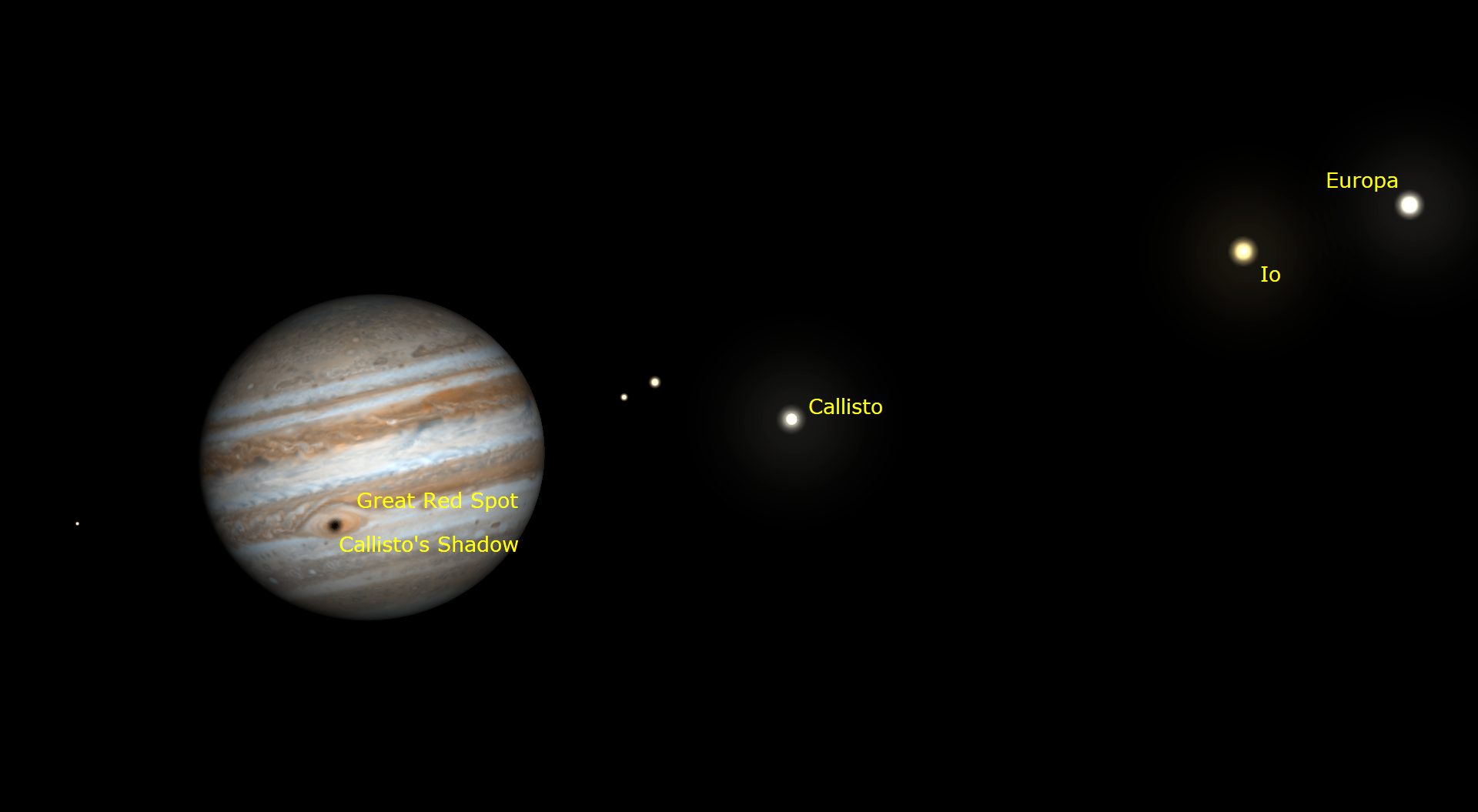

When Callisto’s round, black shadow crosses Jupiter on Friday night, September 17 between 6:15 pm and 11 pm EDT, it will be on, or near, the Great Red Spot – as shown in this simulated view for 8 pm EDT. The shadow will gradually slide to the left of the spot as Jupiter’s rotation outpaces it. The event will be visible anywhere on Earth where Jupiter is shining in a dark sky between about 22:15 GMT on September 17 and 03:00 GMT on September 18. (Stellarium simulated view.)

Hello, September Sky-watchers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 12th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read titled 110 Things to See With a Telescope (in paperback and hardcover) is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers.

The moon will shine in evening skies this week as it waxes from first quarter to next week’s full Harvest Moon. Monday evening’s moon will also feature L-O-V-E when the Lunar X forms. Callisto’s shadow will become the Great Red Spot’s pupil in Jupiter’s eye on Friday, and Neptune and Mercury will each peak in visibility. Use darker skies early in the week to look for the giant Andromeda Galaxy! Read on for your Skylights!

The Sun and the Moon

Once again this weekend, the sun is sporting groups of sunspots that will be visible in safely filtered binoculars and telescopes! They might even be big enough to see unmagnified through eclipse glasses! The spots should remain observable for most of this week as they are carried across the rotating sun. I wrote about sunspots and other solar features here.

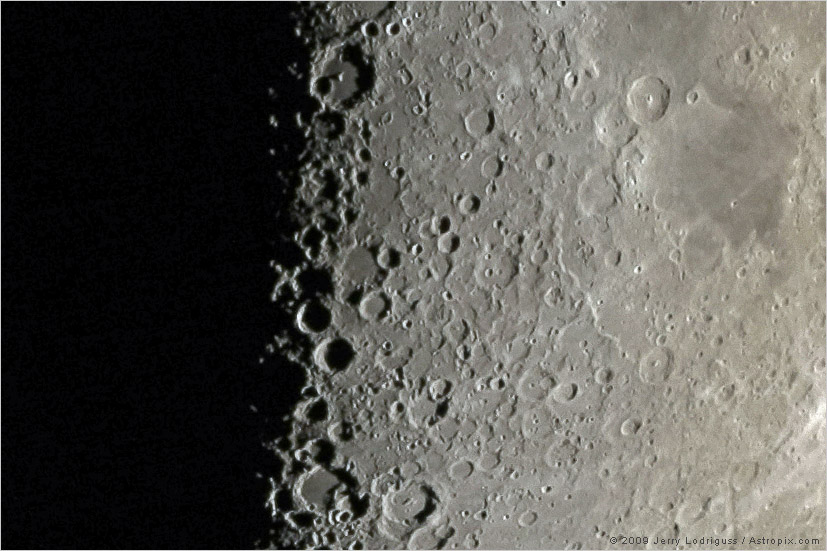

Except for far northerly latitudes, the moon will be shining in the evening sky all over the world this week – a terrific time to examine our celestial sibling through backyard telescopes, binoculars, or just your unaided eyes. While the moon is in its waxing phases, we see it fill with light each night as the terminator, the boundary between the lit and dark hemispheres, slides across the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere, from lunar east to lunar west. For locations on the moon along that pole-to-pole boundary, the sun is rising – so the sunlight arriving there casts long, deep black shadows from every bitty bump and majestic mountain peak. From Earth, it looks spectacular!

The moon’s phases change because it is traveling eastward in its orbit and it is increasing its angle from the sun – by about one moon diameter every hour. That’s why we see the moon hop across the sky and rise later night after night. (After full moon, it decreases its angle from the sun.)

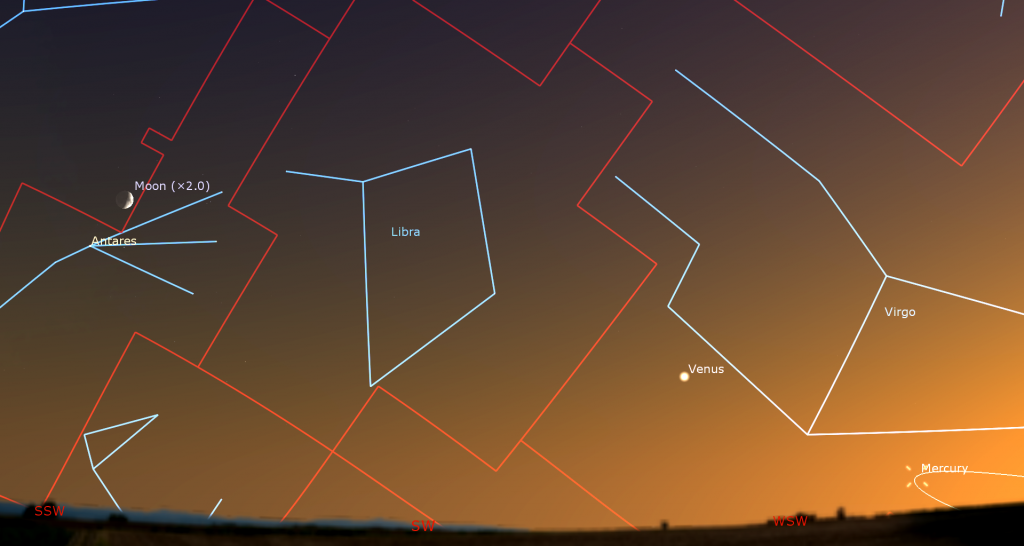

Tonight (Sunday) the almost half-illuminated moon will shine a few finger widths above the bright reddish star Antares, in Scorpius (the Scorpion). The moon will actually be visible faintly in the sky all afternoon, but Antares won’t pop into view above the south-southwestern horizon, until the sky begins to darken. Over the following few hours, they’ll sink toward the southwest.

On Monday afternoon at 4:39 pm EDT, or 20:39 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its First Quarter phase near the medium-bright star named 51 Oph. That star marks the eastern foot of the Serpent-Bearer, Ophiuchus. The term “first quarter” announces that the moon has completed 25% of its monthly trip around Earth – even though it will look 50% illuminated to us Earthlings. On Monday night only, the terminator will be a straight line – then it will increase its curve as the moon waxes gibbous for the rest of the week. Observing the changes in the terminator shape told ancient astronomers that the moon was spherical. There’s a Lunar X on Monday, too. More on that below.

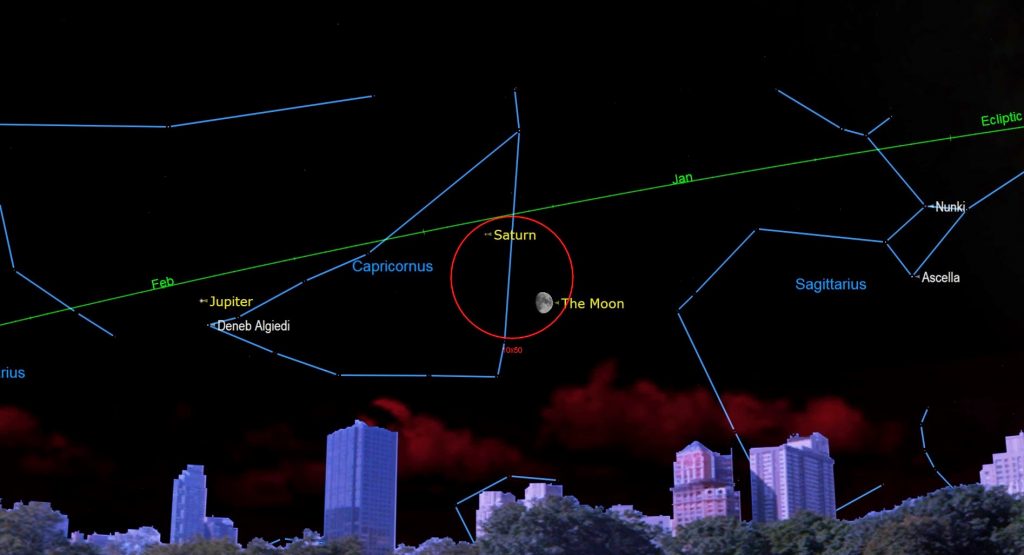

On Tuesday and Wednesday, the bright moon will pass through the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). On Thursday night, the moon will enter the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Luna will shine a slim palm’s width below (or 5 degrees to the celestial southwest of) the yellowish dot of Saturn – with much brighter Jupiter positioned well off to their left (east). While they cross the sky during the night, the moon and the ringed planet will just fit into the field of view of your binoculars. Meanwhile the diurnal rotation of the sky will raise the moon to Saturn’s left before they set together in the west-southwest, at about 2:30 am local time. Look for the giant, curving Apennine Mountains and Lunar Alps in the moon’s upper region on Tuesday-Wednesday, too.

On Friday night, the very bright moon will sit below and between Jupiter and Saturn. The trio will shine in the southeastern sky after dusk, and then cross the southern sky overnight. They’ll make a nice wide-field photo when composed with some interesting scenery – both immediately after dark and then again before Saturn sets, ahead of the other two, shortly before 3:30 am local time on Saturday morning. By that time the moon will be tucked a little closer on Jupiter’s lower left (celestial southwest). Thursday and Friday will also be ideal for seeing the curved Golden Handle shape – the Jura Mountains in the moon’s upper left region.

Finally, the nearly full moon will spend the coming weekend rising among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) at around 7:15 pm local time, just ahead of Monday’s full Harvest Moon.

Lunar X in Early Evening

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in powerful, tripod-mounted binoculars and any size of backyard telescope. When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle by the sun, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape.

The phenomenon is an example of pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent round crater named Werner sits to its lower right (or lunar southeast).

On Monday, September 13 the ‘X’ is predicted to start developing by about 5 pm EDT (or 21:00 Greenwich Mean Time). When the sun’s light first touches the crater rims the X will be indistinct. The shape will intensify to a peak at around 7 pm EDT (or 23:00 GMT), and then gradually fade out over the next hour or two.

Unfortunately, this Lunar X’s peak is during waning daylight for observers in the eastern Americas, and in a bright sky for observers in the west. But the sky will be darker by the time the show ends – and you can always safely observe the moon in binoculars or a telescope during daytime, as long as you take care to avoid the sun. This Lunar X will be visible anywhere on Earth where the moon is shining, especially in a dark sky, between approximately 21:00 on September 13 and 01:00 GMT on September 14.

During a Lunar X event, you can also look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater named Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus which, in combination, resemble Mickey Mouse’s head and ears. In some photographs, a backwards “E” shows above the “L”, allowing you to spell out “L-O-V-E” by using any round crater! I posted a photo of the “letters” here.

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same type of material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers above 60°N latitude miss out.

During this week, if your morning sky is clear and dark, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the twin stars Castor and Pollux. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture it. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

The Planets

Mercury has been lurking above the west-southwestern horizon for a couple of weeks now. With Mercury positioned well below the tipped over evening ecliptic, this appearance of the planet has been a poor one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but has offered excellent views for observers near the equator and in the Southern Hemisphere where Mercury (and Venus) are higher, and in a dark sky. After sunset on Monday, the speedy planet will be just hours away from its widest separation, 27 degrees east of the Sun, and its maximum visibility for the current apparition. On Tuesday evening Mercury will be almost as elongated. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes are around 7:45 pm local time.

This week, extremely bright Venus will emerge from the post-sunset twilight by 8 pm local time and then set at about 9 pm. Due to Earth’s motion around the sun, objects in the sky shift west, and set four minutes later each night. But Venus is holding its own because its eastern orbital motion is off-setting that. Venus will not be positioned much higher than the trees and rooftops, so you might need to walk around until you find an open view to the west-southwest.

Because the inner planets Mercury and Venus are closer to the sun than Earth, they show phases – just like the moon! When viewed in a backyard telescope Venus will exhibit a small, featureless, football-shaped disk because it’s only 67%-illuminated right now. (Mercury is at 55%.) It will grow in size and wane in phase every week. When Galileo saw how Venus changed in phase and apparent size over many months, it convinced him that Venus was a spherical planet orbiting the sun – not orbiting Earth! Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view.

As Venus descends the darkening west-southwestern sky, one-third as bright Jupiter will appear at about the same height towards the southeast. Not long after 8 pm local time, the yellowish dot of Saturn will show up less than two fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right (or 17° to the celestial west). The two gas giants will cross the night sky together amidst the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and then set in the southwest during the wee hours. Sadly, for telescope owners, the low position of the ecliptic on September evenings is keeping those planets in the lower third of the sky, where their light must punch through two to three times as much of Earth’s distorting atmosphere – reducing their crispness. They’ll both look their best at about 10 pm local time, when they’ll climb highest in the southern sky.

Saturn, adorned with its large and bright rings, is a thrilling sight in any telescope! The rings are about 2.4 times the diameter of Saturn’s globe. If your optics are good and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the outer and inner rings. Look for a faint dark belt encircling the planet, too. Take looooong looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. Much fainter Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other, so it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn, and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn (as it is this week). The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower right (celestial southwest) of the planet tonight to above (celestial north) Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Turning now to Jupiter, binoculars and small telescopes will show you the planet’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always appear to be strung like beads along a straight line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line tilts as Jupiter crosses the sky, and the moons’ arrangement varies from night to night.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter this evening (Sunday), late on Tuesday and Thursday evening, Friday evening, and next Sunday evening. It can also be observed during the wee hours on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday morning.

From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Callisto’s shadow will cross with the Great Red Spot on Friday night, from 6:15 pm (in twilight) to 11 pm EDT. For part of that time, the shadow should look like the pupil in the GRS’ “eye”.

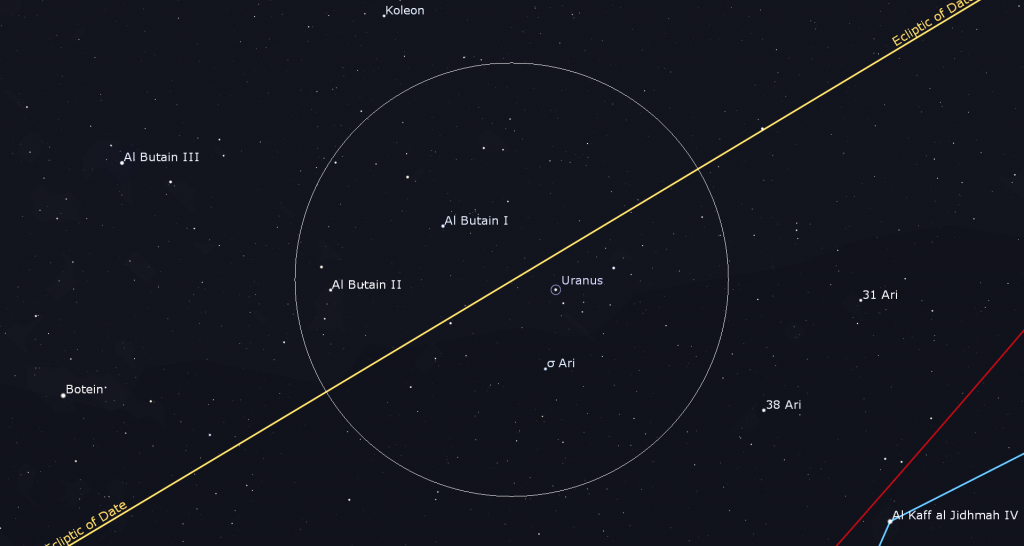

This week Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be observable nearly all night after it rises around 9:30 pm local time. But wait until it has climbed higher in late evening to view it. Uranus is spending all of this year parked below Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram). The blue-green planet is currently surrounded by the moderately bright (5th magnitude) stars Sigma, Omicron, Rho, and Pi Arietis – creating a distinctive asterism for anyone viewing Uranus in binoculars.

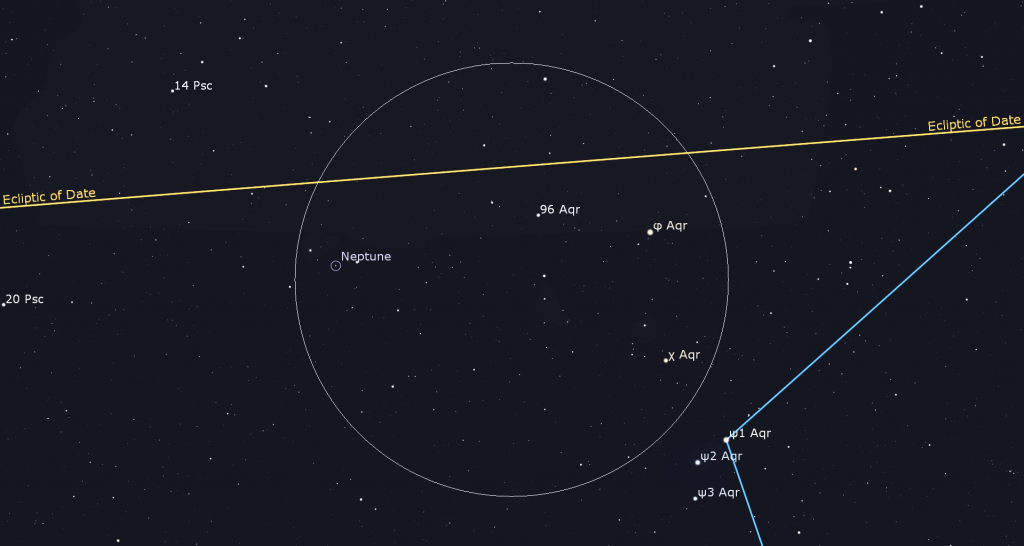

On Tuesday, Neptune will reach opposition. At that time the blue planet will be closest to Earth for this year – a distance of 4.33 billion km, 4 light-hours, or 28.9 Astronomical Units. (1.0 AU is the average Earth-to-sun distance.) Neptune will shine with a slightly brighter magnitude 7.8. Since it’s directly opposite the sun in the sky, it will be visible all night long in good binoculars if your sky is very dark, and in backyard telescopes. Your best views will come after 9 pm local time, when the blue planet has risen higher. Around opposition, Neptune’s apparent disk size will peak at 2.4 arc-seconds and its large moon Triton will be most visible. Neptune will rise at about 7 pm local time and reach peak visibility, halfway up the southern sky, around 1 am local time. Throughout September, Neptune will be located near Aquarius’ (the Water-Bearer) border with Pisces (the Fishes), several finger widths to the left (or 4 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii (φ Aqr). The distinctive three-star grouping named Psi Aquarii (ψ Aqr) will shine to Neptune’s lower right (celestial southwest).

On Saturday, September 11, the main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas reached opposition and its minimum distance from Earth for this year. On the nights near opposition, Pallas rises at sunset and sets at sunrise, and shines with a peak visual magnitude of 8.55. That’s within reach of backyard telescopes – but wait until the asteroid has risen higher for the best view of it, at 9 pm local time or later. This week Pallas is situated in western Pisces (the Fishes), several finger widths to the right (or 4 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the medium-bright star Gamma Piscium.

Giant Galaxy Gazing

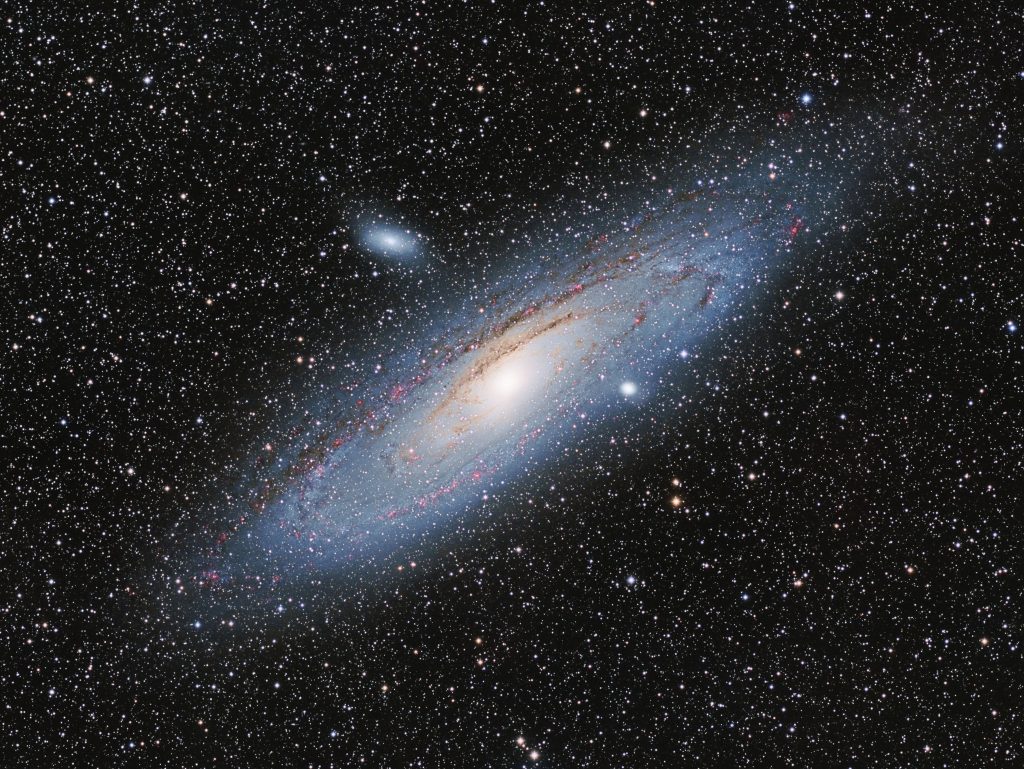

‘Tis the season to look for the farthest object a human eyeball can see without help* – the Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31. This large spiral galaxy is a sister to our own Milky Way galaxy. It sits 2.5 million light-years away from our sun, meaning that its stars’ light has been journeying for that length of time. And, if there are alien astronomers there looking at us, they are seeing our solar system as we were 2.5 million years ago!

Under dark skies, using unaided eyes only, you should be able to see a faint fuzzy patch that is elongated left to right. The galaxy spans six full moon diameters across the sky, but only its bright core and the surrounding, inner halo are usually seen visually. The galaxy is quite easy to see with binoculars. (It will become harder as the moon brightens during this week – so look sooner than later. Or wait for the moonless period in a couple of weeks.)

Because telescopes have fields of view that are too narrow to see the entire galaxy, they’ll generally only show you Andromeda’s bright core. While looking, see if you can see M31’s two small, fuzzy-looking companions, the small elliptical galaxies designated M32 and M110. M32 is closer to the main galaxy’s core and it situated just to the lower right (or to the celestial south). M110 is above (or northeast of) the main core and is slightly farther away. At 2.49 million light-years, M32 is closer to us than the Andromeda Galaxy; while M110 is 200,000 light-years farther away. (Your telescope will probably flip and/or mirror image those directions.)

In mid-September, the Andromeda Galaxy is less than halfway up the east-northeastern sky at 9 pm local time – and higher later on. To locate it, you can first find the medium-bright star Mirach. It’s the second star when hopping left (celestial east) from Alpheratz, which marks the eastern corner star of the Great Square of Pegasus. Then look for a dimmer star a few finger widths above (or 4° NE of) Mirach. The Andromeda Galaxy is higher again by that same distance. Alternatively, you can use the highest three stars of the W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). They form an arrow that points directly at M31. The giant galaxy is a cool object to see! Let me know if you view it.

*Another large galaxy, called Messier 33 in Triangulum (the Triangle), is 2.75 million light-years away. Observers with very keen eyes under very dark sky conditions can sometimes see it, too – setting the record. This galaxy is tougher because it is oriented nearly face-on to Earth – so its light is spread across a large patch of sky (equal to 1.5 full moon diameters), making it dimmer overall. It sits only 1.3 fist diameters below M31, a palm’s width below the star Mirach.

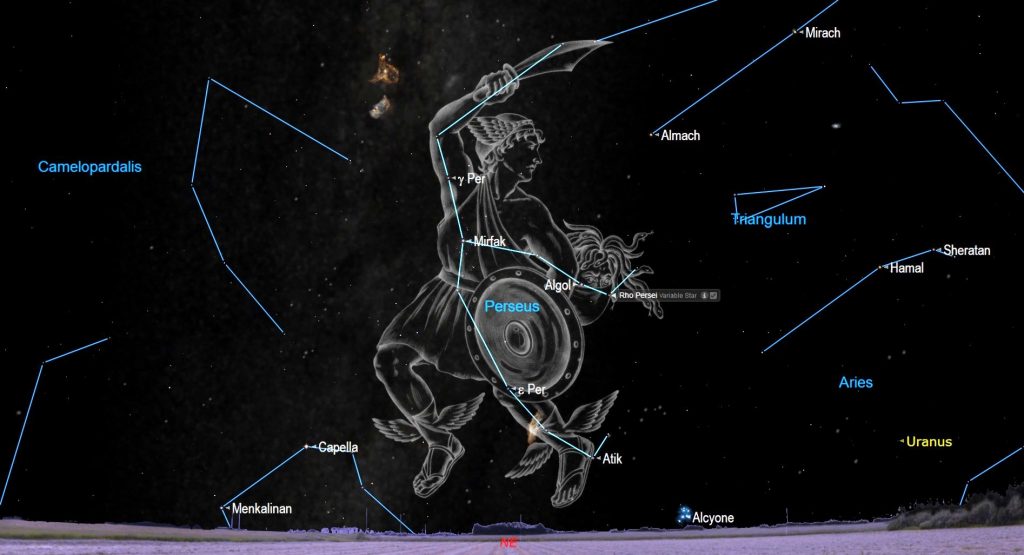

Watch Algol Brighten

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol’s visual brightness dims and re-brightens noticeably. This happens because a companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae). But at maximum eclipse, Algol’s magnitude 3.4 is almost the same brightness as Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star sitting just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south). On Wednesday, September 15 at 9:40 pm EDT (or 01:40 GMT on September 16), Algol will be at its minimum brightness, and sitting low in the northeastern sky. Five hours later Algol will shine at full brightness from a point nearly overhead in the eastern sky.

Soaring with Cygnus

If you missed last week’s flight into Cygnus (the Swan), I posted it here. You can still enjoy many of its treats this week.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns this week! On Tuesday, September 14 we’ll cover our recommended astronomy and space books. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here. Note: If you registered for the Zoom series last year, you will have received an email asking you to please re-register before Tuesday. (We’re cleaning out older unused registrations to make room for new viewers from libraries across Canada this fall.)

Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but we are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Sunday afternoon, September 19 from 1 to 2 pm EDT, join me for Ask an Astronomer. During these family-friendly sessions, I’ll answer your questions about the universe and review what’s up nowadays. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., September 8, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!