Autumn Stars Approaching, the Waxing Moon and Planets in Evening, and Northern Crown Jewels a-Shining!

On Saturday, September 3, 2022, the moon will reach its first quarter phase. (Starry Night Pro)

Hello, September Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 28th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will return to shine in the evening sky worldwide this week, but we can still enjoy double stars and variable stars, such as the ones in Corona Borealis. All the planets are observable from dusk to dawn. Although Venus and Mercury are becoming a challenge, the rest of the bright planets will be easy in binoculars and telescopes. Read on for your Skylights!

Welcome to September! We’re only three weeks away from the equinox. At this time of year, the sun is rising about 1 minute later and setting about 1.5 minutes earlier at mid-northern latitudes, giving us three more minutes of darkness each day. Astronomers also appreciate that those earlier sunsets allow the summer constellations to remain visible in the west after dusk while we transition to the autumn sky overhead. Meanwhile, night owls will see the winter stars of Auriga (the Charioteer) and Taurus (the Bull) peeking over the eastern horizon at midnight!

The Moon

Tonight (Sunday) you might catch a glimpse of the young crescent moon’s sliver floating a few finger widths above the western horizon for about half an hour after sunset – but the post-sunset twilight, and any clouds or haziness, could make seeing it a challenge. The closer to the equator you live, the easier it will be.

Unlike our Western Gregorian calendar, a lunisolar calendar uses the 29.53-day cycle of the moon’s phases (its synodic period) to define the months of the year – usually starting each month on the day when the young crescent moon is first glimpsed after sunset. Nowadays, we use astronomy apps to tell us when that will happen, whether one can see the moon or not.

The placement of those months is anchored to a solstice or equinox. Since solstices and equinoxes are Earth-Sun phenomena, and completely independent of the moon’s phases, lunisolar calendars drift compared to our Gregorian system. Since the moon runs through its cycle 12.37 times per year, every second or third lunisolar year requires an extra 13th intercalary or “leap” month. Seeing the youngest possible moon is a bucket-list item for many astronomers.

The moon will become easier to see each evening this week as it slides farther from the sun – shifting by its diameter every hour. That change in angle from the sun will allow the moon to set 20 minutes later each day, and will increase the amount of the moon we see illuminated, i.e., its phase. Tonight, the moon will also be accompanied by the medium-bright dot of Mercury shining about a fist’s diameter to the moon’s left (or 10° to the celestial SSE). On Monday evening, the moon will shift to sit a palm’s width above Mercury. Take care to avoid using binoculars or telescopes to find them until the sun has completely set.

The moon will spend Sunday through Wednesday traversing the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden). On Tuesday, look for the bright white star Spica twinkling to the moon’s lower left in a darkened sky – around 9 pm local time.

Wednesday evening and onward will be the best nights to view the moon in binoculars or a backyard telescope. (The moon will be higher and in a darker sky, giving you crisper views.) As the pole-to-pole terminator, the boundary that separates the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres, sweeps westward across the moon, the lunar terrain along the terminator will be dramatically lit by nearly horizontal rays of sunlight, casting long shadows from every peak, crater rim, and ridge. Many craters will have bright rims and black floors, some with bright central mountain peaks. The terminator slowly shifts hour-by-hour and night after night, so check in regularly!

On Thursday the 31%-lit crescent moon will be shining among the medium-bright stars of Libra (the Scales). Watch for the bright star Zubenelgenubi, meaning “the southern claw of the Scorpion” shining a few finger widths to the upper right of the moon. Even the low magnifying power of binoculars will reveal that Zubenelgenubi is actually two close-together stars. The stars of Libra used to considered part of Scorpius!

In the southwestern sky after dusk on Friday, the nearly half-illuminated moon will shine in western Scorpius jus to the right of the up-down row of small white stars that form the scorpion’s claws. From top to bottom, the stars are named Jabbah or Nu Scorpii, Graffias or Acrab, Dschubba, Fang or Pi Scorpii, and Rho Scorpii. Graffias, Dschubba, and Fang are the brightest. A backyard telescope at high magnification will reveal that Nu Scorpii, Graffias, and Dschubba are close-together double stars.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its trip around Earth on Saturday at 2:08 pm EDT or 11:08 am PDT and 18:08 Greenwich Mean Time. Its 90° angle away from the sun will cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side. The terminator is a straight line on a first quarter moon, proof to the ancients that the moon was a sphere. At first quarter, the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky, too. On Saturday night, the moon will be sitting to the upper left of the bright reddish stars Antares, the heart of the scorpion. Watch for plenty of twinkling from that low-in-the-sky star.

On next Sunday night, the then waxing gibbous moon will sit several finger widths to the upper right (or 3.5° to the celestial northwest) of the medium-bright star named Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii), which marks the tip of the spout of the tilted Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

You’ll be able to enjoy the moon until it sets towards midnight local time, so take the fine opportunity to view the spectacular, mountain chains (actually segments of the old basin’s rim) that encircle the rim of Mare Imbrium, the large, dark, circular feature located above the moon’s equator. The most northerly arc of mountains is the Lunar Alps, or Montes Alpes. Good binoculars or any telescope will reveal a slash cutting through them called the Alpine Valley, or Vallis Alpes, where the moon’s crust has dropped between parallel faults. To the lower right (lunar southeast) of the Alps are the Caucasus Mountains, or Montes Caucasus. That mountain range disappears under a lava-flooded zone connecting Mare Imbrium with Mare Serenitatis to the southeast. The southeastern edge of Mare Imbrium is bordered by the lengthy Apennine Mountains, or Montes Apenninus. They sink out of sight near the prominent crater Eratosthenes. The Montes Carpatus ring the south, near crater Copernicus, which will sit along the terminator.

The Planets

We’ll still be able to see all the planets between sunset and sunrise this week, but the two innermost planets will be challenging unless you are viewing them from tropical latitudes. Mercury will lurk just above the western horizon after sunset all week long, but its position below a very slanted ecliptic will keep the speedy planet too low for easy viewing from mid-northern latitudes as it drops a bit lower each night. Don’t forget that the young crescent moon will shine a fist’s diameter to Mercury’s right on Sunday, August 28. Meanwhile, extremely bright Venus will rise in the east by about 5:30 am local time this week – but it won’t climb very high before sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. Venus, too, is slowly descending toward the sun, so we’ll lose sight of it completely around mid-September.

Look for the medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn shining above the southeastern horizon after dusk. Saturn will look best in a telescope when it’s high in the southern sky around midnight, but you can certainly start viewing it as soon as you like. It will set in the west-southwest before dawn. Saturn’s peak viewing window will shift earlier by half an hour with each passing week.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings encircling its little globe. The rings will close up, i.e., become more edge-on to us, every year until the spring of 2025. This year Saturn’s southern polar region has extended well beyond them. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one. Over the coming weeks, Saturn’s slide to the west of the anti-solar point will cause the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the planet. Where it sits will depend on how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from below (celestial south of) the planet tonight (Sunday) to above (celestial northwest of) the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

This year Saturn is shining among the faint stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The two small stars shining a thumb’s width apart to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial southeast) are Deneb Algedi on the left (east) and Nashira on the right (west). They represent the tail of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Since Saturn is moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more into a line with those stars every week. (Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the distant planets and asteroids “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars.)

The minor planet designated (4) Vesta orbits the sun in the main asteroid belt. Just recently opposite the sun in the sky, Vesta will be visible all night long this week, and shine at nearly its brightest for the year (magnitude 5.7) – well within reach of binoculars and small telescopes. Look for the asteroid in southwestern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), approximately midway between Saturn and the bright star Fomalhaut. This week, Vesta will be shifting west from nearby the medium-bright stars named 41 Aquarii and 47 Aquarii.

This week, extremely bright, white Jupiter will rise above the eastern horizon around 9 pm local time, and then spend the night chasing 17 times fainter Saturn across the sky. Jupiter will climb high enough to look good in any telescope around 11 pm local time – and will look sharpest during the wee hours. Early risers can spot the planet a third of the way up the southwestern sky before sunrise. Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, which complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four of them, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter – or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth hours, we can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pale-looking Great Red Spot cross the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday evening, and also during the wee hours of Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday morning. The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. Io’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter on Wednesday evening from 9:45 am to 11:55 pm EDT.

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is positioned between Jupiter and Saturn nowadays. It’s theoretically observable in binoculars, but a good telescope will make it easier. This month, the distant planet’s faint, blue speck will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right, and a thumb’s width to the upper right (or 1.8° to the celestial west-southwest) of a small star named 20 Piscium. Neptune has a large moon named Triton that is visible in large aperture telescopes, especially during the next couple of months when we’re closer to the planet.

The medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon around 11:30 pm local time and will be decent views in a backyard telescope by about 1 am local time. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. Watch for the bright little Pleiades star cluster shining a palm’s width above the planet. Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. We’re 150 million km from it now.

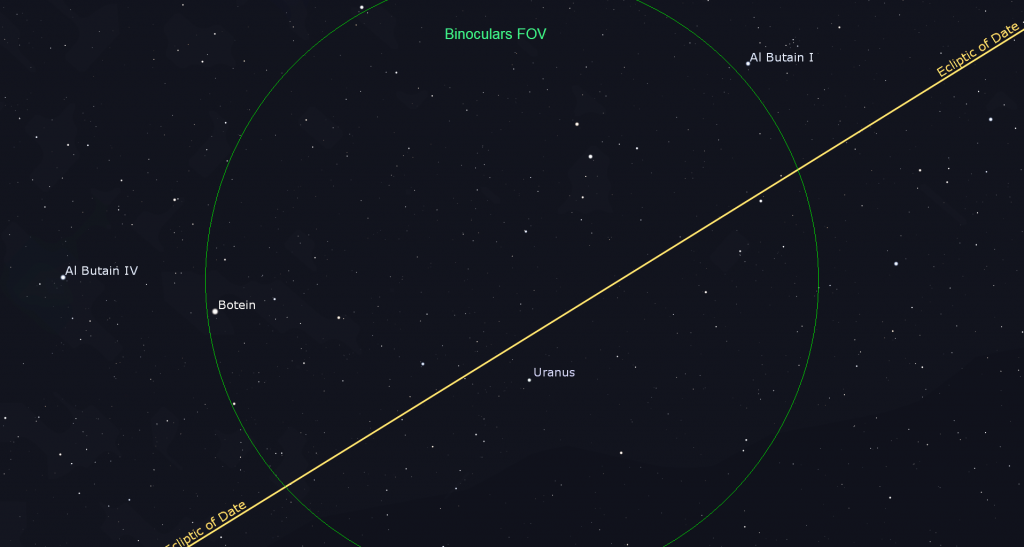

Magnitude 5.72 Uranus will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, after about midnight local time this week. The blue-green speck of the planet is located nearly two fist widths to the upper right (or celestial west) of Mars. Since Mars is speeding away eastward, their separation will grow from 16° to 20° over this week. Without Mars to help you, the brightest guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Ram. I’ll post a star chart here. Uranus will be easiest to see when it’s higher in the sky in the hour before dawn.

The Northern Crown is in the West

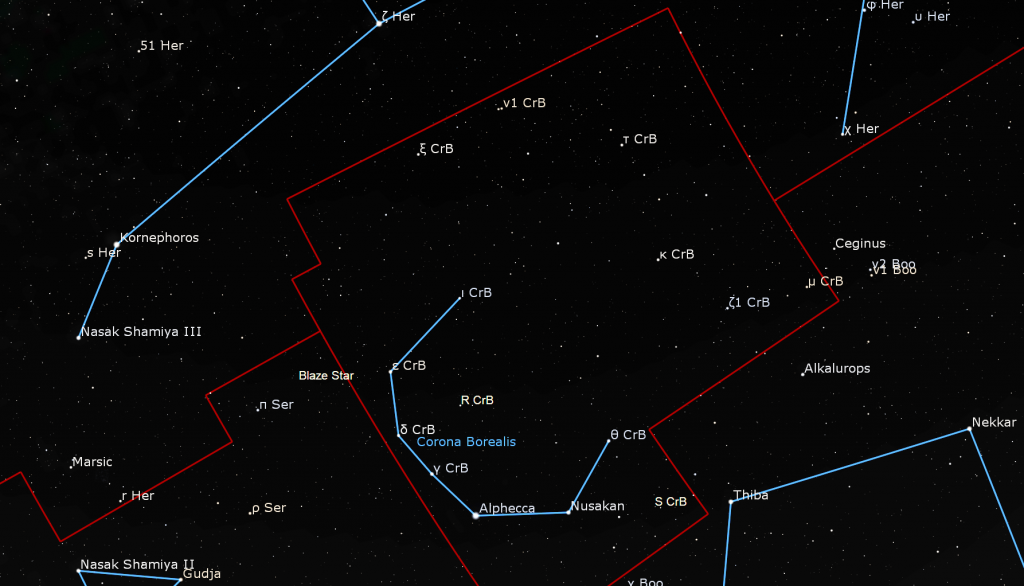

Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown) can be spotted halfway up the western evening sky in early September. The constellation actually sits about midway along the imaginary line that joins the two very bright stars Vega, which shines nearly overhead, and Arcturus, which is lower in the west. The earlier autumn sunsets extend our opportunity to explore Corona Borealis. This incomplete circlet of medium-bright stars is roughly 7 degrees across (a generous palm’s width). It is both a constellation and an asterism (an informal star pattern). Corona Borealis’ brightest star Alphecca is a white, A-class star located 75 light-years from the sun. Alphecca’s placement in the constellation is reminiscent of a diamond in a ring. The star’s name derives from the Arabic expression for “broken”, referring to the incomplete ring.

While the Northern Crown is poor in deep sky objects, it contains several interesting jewels that are tolerant of some moonlight – double stars and variable stars. The side-by-side pairs of stars named Nu1 and Nu2 Coronae Borealis (or ν1,2 CrB) are easily seen in binoculars and any telescope. They are located 4 finger widths to the lower right (or 4.5° to the celestial WNW) of the bright star Zeta Herculis, which sits at the lower corner of Hercules’ keystone-shaped body. The two stars of Zeta 1,2 CrB can be split apart using any telescope. To the unaided eyes they look like a single medium-bright star located a slim palm’s width above the star Thiba in Boötes, or a fist’s width to the upper right of Alphecca. A slightly closer-together double star named Struve 1964 will share their eyepiece view, if you don’t zoom in too much. Scan around and look for more!

Alphecca itself is an eclipsing binary system that varies in brightness by a tiny amount every 17.36 days, similar to the behavior of the star Algol in Perseus (the Hero). Variable stars of the eruptive type were first recognized as being like the star R Coronae Borealis, which is located about three finger widths above (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial northeast of) Alphecca. R Corona Borealis is a hydrogen-deficient and carbon-rich supergiant star. From time to time, it’s usual visual magnitude of 5.8 drops to as little as magnitude 14, effectively vanishing – possibly due to the formation of opaque carbon dust that blocks visible light, but continues to pass infrared wavelengths. Hello, James Webb Space Telescope!

Another star named S Coronae Borealis exhibits the same range of variability as R CrB, but with a 360-day period. The Blaze Star (or T Coronae Borealis) is a cataclysmic variable star, also called a recurrent nova-type star. Normally shining between visual magnitude 10.2 and 9.9, on rare occasions it has brightened to magnitude 2 in a period of hours, caused by a nuclear chain reaction and the subsequent explosion. During those times, this normally hidden star becomes bright enough to see even in light-polluted skies!

Aquila the Eagle

If you missed last week’s tour of the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle), I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Thursday, September 1 at 8 pm EDT, the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics at the University of Toronto will stream their AstroTour. The live, free event will feature Dr Mubdi Rahman, the Founder and Principal of Sidrat Research, a Research Associate at the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, and an Assistant Research Scientist at the Johns Hopkins University. He will discuss Rediscovering our Scientific Heritage: A Journey through Classical Islamic Astronomy. Details and the YouTube link are here.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, September 2, from 6 pm to 11 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, September 13 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll learn about variable stars! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!