Bright Giants in Evening, The Young Moon Veers Past Venus, and Pegasus Flies High!

This image of the bright globular cluster Messier 15 in Pegasus was taken by Ron Brecher in February, 2015. This image spans about one degree of the sky. Ron’s galleries of fine astro-images can be enjoyed at his website www.astrodoc.ca

Hello, October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 3rd, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read titled 110 Things to See With a Telescope (in paperback and hardcover) is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers.

Until the coming weekend, which the young crescent moon will spend passing Venus after sunset, the moon will mainly be out of the evening sky this week – allowing us to enjoy the Great Square of Pegasus. Meanwhile, the bright planets Jupiter and Saturn will catch your eye in evening, and the ice giants Uranus and Neptune will be observable in telescopes all night long! Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will begin this week swinging sunward in the eastern pre-dawn sky. On Monday morning before dawn, its very slim crescent will shine near the tail stars of Leo (the Lion). On Tuesday morning, you might catch a final glimpse the old moon sitting just above the eastern horizon before sunrise.

The moon will pass its new phase on Wednesday at 7:05 am EDT or 11:05 Greenwich Mean Time. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon will be unobservable from anywhere on Earth – until its very slim young crescent appears just above the west-southwestern horizon on Thursday after sunset.

From Friday to Sunday, the crescent moon will share the western post-sunset sky with the very bright planet Venus. The moon will sit to the right of Venus on Friday. On Friday and Saturday, look for Earthshine, sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the dark hemisphere of the moon. The moon will be a little larger than average on Friday evening because it will be at perigee, its minimum distance from Earth for this month.

As the sky darkens after sunset on Saturday, the orbital motion of the moon will have shifted its slim crescent just above (or 2 degrees to the celestial north of) Venus – easily close enough for them to share your binoculars’ field of view. Sharp-eyed skywatchers who can spot the moon in late afternoon can also try to see Venus’ bright speck below it in daytime, even without binoculars! After the sky darkens at about 7:30 pm in your local time zone, the fainter claw stars of Scorpius will appear around the moon and Venus. Finally, on Sunday, the moon will be poised to the east of Venus. Take pictures of them!

With the moon absent in the first half of the week, and then barely illuminated and setting early in the second half of the week, skywatchers around the globe will enjoy dark skies. More on that below!

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same type of material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers above 60°N latitude miss out.

If your location favors it, between now until the full moon on October 20, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below Leo’s brightest star Regulus. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture it. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

The Planets

As I mentioned above, this week will see the crescent moon dance past Venus in the western sky after sunset. The extremely bright planet should emerge from the post-sunset twilight by 7 pm local time and then set around 8:30 pm. Venus will not be much higher than the trees and rooftops, so you might need to walk around until you find an open view to the west-southwest. Once the sky has darkened more, the bright, reddish star Antares will appear twinkling to Venus’ left.

When viewed in a backyard telescope Venus will exhibit a small, featureless, football-shape. That’s because it’s only 60%-illuminated right now – due to its position well east of the sun. Venus will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. Or, use the nearby crescent moon to see Venus in daytime on Saturday (as I described above)!

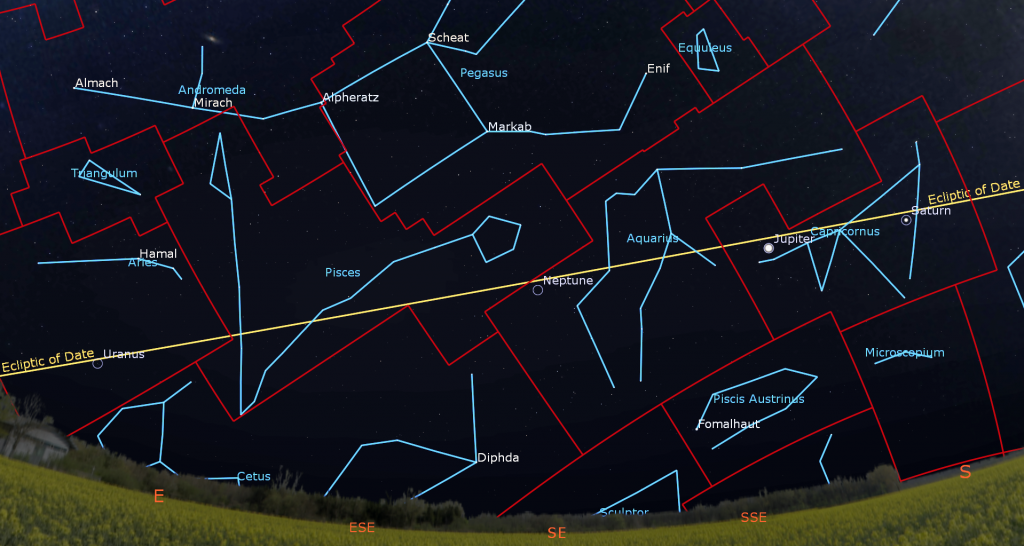

While Venus descends the darkening west-southwestern sky, one-third as bright Jupiter will show up in the southeastern sky. After 7:30 pm local time, the yellowish dot of Saturn should also appear, shining less than two fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right (or 16° to the celestial west). The two gas giants will cross the night sky together amidst the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and then set in the southwest between 2 and 3 am. Sadly, the low position of the ecliptic on September evenings is keeping those planets in the lower third of the sky this year, where their light must punch through two to three times as much of Earth’s distorting atmosphere – reducing their crispness in telescopes. Starting next year, the eastward orbital motion of the two planets will shift their best viewing months from summer into autumn, when they’ll sit be able to shine higher in the sky.

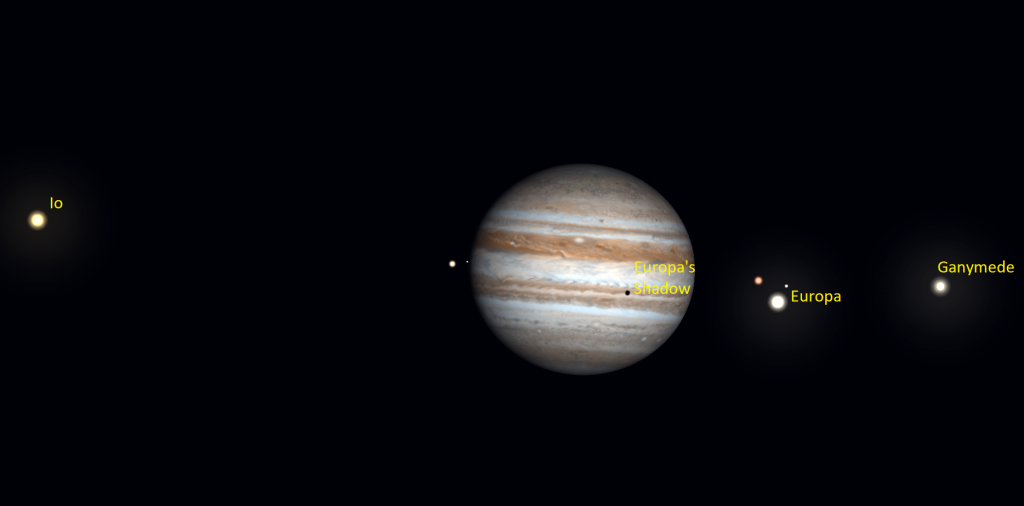

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always appear to be strung like beads strung in a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line tilts as Jupiter crosses the sky, and the moons’ arrangement varies from night to night.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday after dusk, and in late evening tonight (Sunday), Wednesday, and Friday. It can also be observed after midnight tonight, Tuesday, and next Sunday night.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Europa’s small shadow will cross from 6:45 to 9:25 pm EDT on Thursday night.

Saturn’s thrilling rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings. Look for a faint, dark belt encircling the planet, too. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. Much fainter Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other, so it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn, and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn (as it is this week). The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the lower left (celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Distant, blue Neptune is in the sky all night long, near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes) – and roughly three fist diameters to the left (or celestial east) of Jupiter. This moonless week will be a good time to observe the magnitude 7.8 planet. To help you find it, use binoculars to locate the up-down grouping of five medium-bright stars Psi, Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). (Psi Aquarii is a triple star!) The little blue dot of Neptune will sit several finger widths to the left (or 4 degrees to the celestial NNE) of the top star, Phi. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is near those stars, too – a palm’s width to the upper right (northwest) of them, near the brighter star Hydor. (2) Pallas is still shining at close to peak brightness for 2021.

This week Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be observable from late evening onward – especially after midnight, when it will have climbed almost halfway up the southeastern sky. Slow-moving Uranus is spending all of this year parked below Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram). It’s also positioned about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial WSW) of the Pleiades star cluster. The blue-green planet is amidst the moderately bright (5th magnitude) stars Sigma, Omicron, Rho, and Pi Arietis – creating a distinctive asterism for anyone viewing Uranus in binoculars. This is a good week to seek it out, since the bright moon will be away.

Both Mercury and Mars are out of sight nowadays. They both pass solar conjunction at week’s end. Mercury will soon re-appear in the eastern pre-dawn sky, and Mars will join it in early November.

Pegasus Flies on High

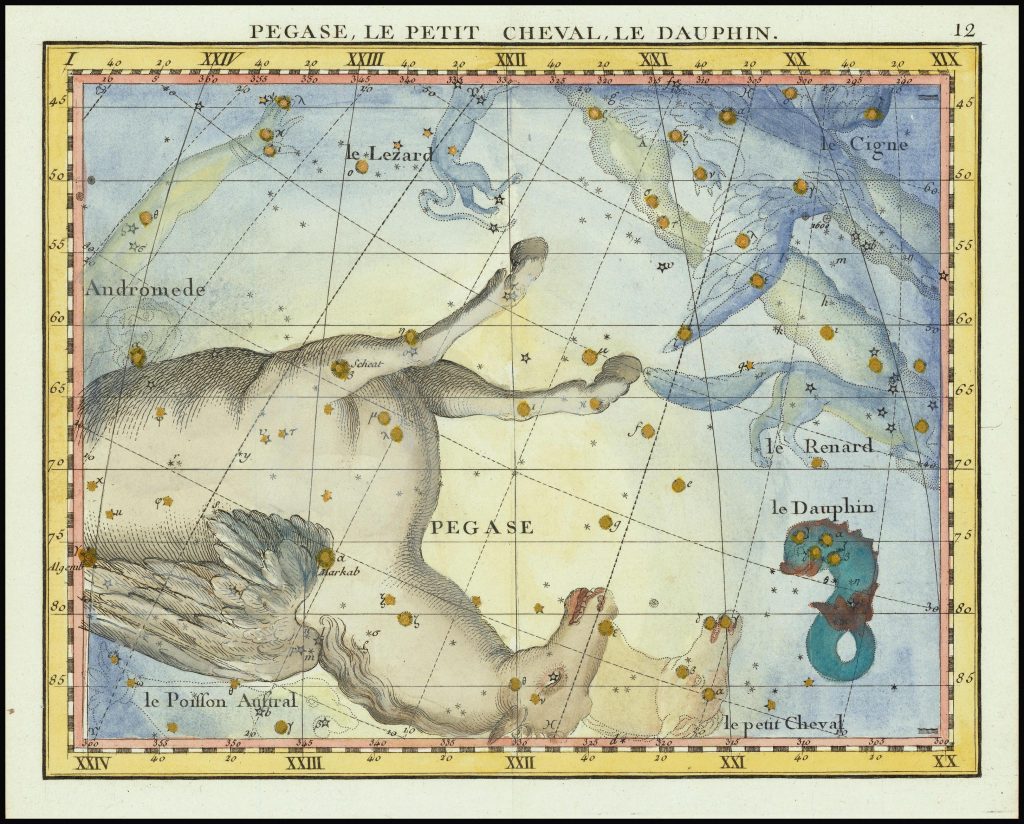

Fall and winter evening skies feature a group of easy-to-see constellations that are characters in a grand story from Greek mythology – the tale of Princess Andromeda and her rescue by the hero Perseus. I’ll relate that tale in a future Skylights. This week, we’ll look at Pegasus – the westernmost constellation in the myth. But, first, let’s flesh out that story a little more…

Before hunting the Gorgon Medusa, Perseus was given some magical gifts to aid him in his quest, including winged silver sandals called the Shoes of Swiftness. Immediately after slaying the snake-haired Medusa by cutting off her head, he flew into the air to avoid Medusa’s angry sisters. While hovering there, some of the gorgon’s blood dripped onto the seashore below. Poseidon, god of the Sea, mixed the blood with some sea foam, and the magical flying horse Pegasus, whose name is related to the Greek word for wellspring “pegai”, sprang from the sea.

Pegasus has traditionally been associated with beauty, wisdom, and poetry. In some stories, the majestic, wild, white stallion was tamed by the warrior Bellerophon, the most successful hero of ancient Greece (until Hercules came along later). After many heroic deeds astride Pegasus, Bellerophon felt that the he was worthy of living in Olympus with the gods, and attempted to ride Pegasus there. But the Olympians denied him – sending a bee to sting Pegasus, who bucked and tossed Bellerophon from his saddle. The hero died from the fall to Earth, but he has an interesting role among the stars – as we’ll cover below. Zeus then added Pegasus to his stables, using him to transport thunderbolts. As a reward for his service, at the end of the horse’s days, he was granted a place among the stars.

The constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse) appears in the eastern evening sky in September, becomes well placed for evening astronomy, high in the southern sky from October to December, and then gradually sinks into the western twilight by February. It is one of the largest and oldest of the 88 modern constellations – 7th by area. Since it occupies a place in the sky just north of the celestial equator, it is visible from almost everywhere on Earth. Only Antarctica never sees it rise.

Pegasus has traditionally been depicted upside-down, with stars representing his wings, and chains of stars extending westward forming his head and neck, and two front legs. The stars where the rest of him should be are occupied by the water constellation of Pisces (the Fishes) – with Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) situated to the right (west), below Pegasus’ head. According to some scholars the ancient Phoenicians envisioned Pegasus as a bridled horse affixed to the prow of their ships – explaining his missing hindquarters and the nautical theme of the surrounding constellations.

To the right (or celestial west) of Pegasus’ head is a tiny and dim constellation composed of four stars called Equuleus (the Little Horse). Some cultures referred to Pegasus as the Second Horse, because Equuleus rose first and led the way across the sky. Beyond Pegasus’ forelegs sits the prominent constellation of Cygnus (the Swan), with its bright Summer Triangle star Deneb. Between Cygnus and Equuleus swims tiny Delphinus (the Dolphin). Lacerta (theLizard) scampers to the north of Pegasus – “under” the horse’s front feet. Finally, adjoining Pegasus on the left-hand (eastern) side, and sharing one major star with him, is Andromeda (the Princess).

Pegasus contains one of the most obvious asterisms in the sky. (An asterism is a shape or pattern made up of prominent stars, and it can use some of the stars in a single constellation, or combine stars from adjacent constellations. The Big Dipper is an example of the former case, since the dipper uses only part of the large constellation Ursa Major.) Pegasus’ asterism is a giant square of four equally bright stars called the Great Square of Pegasus. The shape will probably remind you of a baseball diamond when you see it, because it’s usually tilted with one corner downwards.

For the Lakota people, the square represented the great shell of Keya, the Turtle. The Anishinaabe of the Great Lakes region view the square as the torso of Mooz, the Moose. Using unaided eyes only, from the suburbs, the Great Square appears empty. Look carefully for two dim stars offset slightly from the centre of the square – they represent the moose’s heart. Hunting of the moose is only allowed while Mooz is visible in the night sky. That way, the young can be safely born in spring.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Pegasus make up the Black Tortoise of the North, one of the four legendary Benevolent Animals in the stars. The nomadic Arabs saw the square as “Al Dalw”, the “Water bucket” of Aquarius. To draw water from a deep well, desert travelers would take a water skin and prop the mouth open using crossed sticks lashed to each corner, forming a square opening. When empty, the water skin could be stowed flat or rolled up on the flanks of a camel. The square may also have been, “Al ‘Arkuwah”, the well in which such a bucket was used.

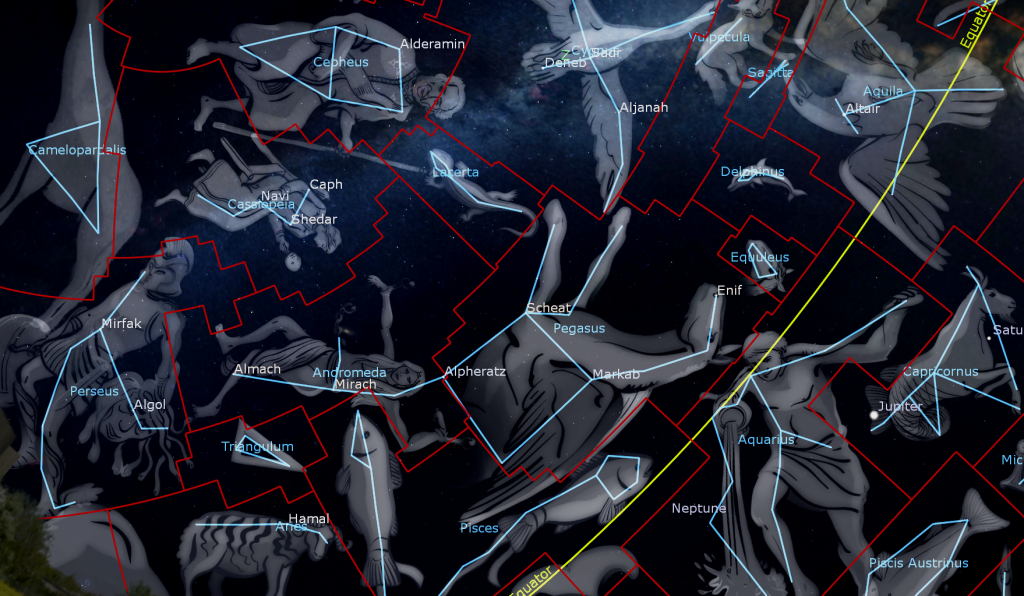

Let’s tour Pegasus. After it gets dark, face the southeastern sky. The square’s edges are about 16° long (or 1.6 fist widths when held at arm’s length), and about 20° from corner to corner. In early October at 9 pm local time, the square’s centre is halfway between the horizon and the zenith. It’s highest in the southern sky at midnight. It will set in the west by dawn.

The star at the southeast corner (bottom) of the diamond is Algenib, derived from the Arabic for “the Side”. It’s a very hot blue-white star of moderate brightness that sits about 350 light-years away from us, and actually emits 4,000 times more light than our sun! Moving counter-clockwise, the white star at the right-hand corner is Markab “the Saddle”. This star appears slightly brighter than Algenib – it emits less light, but it is only 140 light-years away.

From Markab, look right (west) for the dimmer stars that trace the horse’s neck and head. A palm’s width from Markab is blue Homam “Man of High Spirit”, then another fist’s width further on sits Biham. Both are about equal in brightness. A somewhat fainter star named Al Fum al Faras “the mouth of the horse” is located a thumb’s width to the right (celestial southwest) of Biham.

From Biham look a palm’s width higher to the right for bright star Enif “the Nose”. Enif is a cool, orange supergiant star located 670 light-years away from us. It is nearing the last stages of its life cycle. You should be able to perceive that its colour is tinted. Enif is huge! Were it to replace our Sun, it would span 40° of Earth’s sky, eighty times wider than the Sun or Moon! Enif is just at the lower mass limit for dying in a supernova explosion. Use binoculars to scan the sky about four fingers widths to the west of Enif. You’ll find a small, dim, but pretty, fuzzy patch of stars designated Messier 15. That globular star cluster is 33,000 light-years away from us.

Returning to the square, the fairly bright, magnitude 2.4 star at the northwest (top) corner is Scheat “the Foreleg”, the second brightest star in the constellation. It’s a cool, red giant star located 200 light-years away from us. Pegasus’ two front legs start at Scheat and extend upwards to the right. Five degrees to the right of Scheat is the dim yellow star Matar “Lucky Star of Rain”, and the leg terminates a palm’s width farther in the same direction at a double star designated Pi Pegasi or π Peg. Using binoculars you should be able to see that Pi consists of two close-together, yellow-white stars.

The second foreleg takes a jog to the lower right before bending back up parallel to the first one. A well-spaced pair of yellowish stars named Sadalbari “Luck Star of the Splendid One” and Lambda Pegasi or λ Peg marks the knee. The foreleg extends to a faint white star a fist’s width to the upper right, and ends at a dim white star an additional 5° away.

There’s a dim yellow star sitting a thumb’s width just outside of the baseball diamond, midway between the top and right corners. This is the sunlike star designated 51 Pegasi. It hosts the first exoplanet ever discovered, in 1995! Informally dubbed Bellerophon, and now named Dimidium, it is a Jupiter-sized planet that orbits 51 Pegasi every 4.23 days at a distance much closer than Mercury does in our solar system. Planets like this are called hot Jupiters. Take a look at the star in your binoculars and let your imagination soar, like Bellerophon!

The final star of the square, at the northeastern (left-hand) corner, is called Alpheratz “The Horse’s Shoulder”. It’s another hot, blue-white supergiant star, but located only 97 light-years away from us. The spectrum of this star’s light indicates that it is highly enriched in the metal Mercury. In actuality, Alpheratz does not belong to Pegasus. It’s the brightest star in Andromeda, and marks the princess’ head – but that’s a tour for another day!

Referring back to the water bucket concept, in Arabic astrology, the westerly stars of the Great Square, Markab and Scheat, were together called Al Fargh al Mukdim, the fore-spout (of the bucket). The eastern two stars, Algenib and Alpheratz, were called Al Fargh al Thani, the rear spout. Those two fainter stars inside the square are Tau Pegasi and Upsilon Pegasi, or Salm “a Leather Bucket” and Al Karab “the Bucket-rope”. They may also represent the intersection of the lashed-together sticks holding the bucket open!

For Skylights readers with good-sized telescopes, Pegasus is loaded with galaxies! This is because the constellation sits well away from the obscuring gas and dust of our Milky Way, allowing us to peer deeper into the Universe. One of my favorite sights is NGC 7479, also designated Caldwell 44, an S-shaped spiral galaxy that resembles Superman’s sigil. In fact – the galaxy’s nickname is the Superman Galaxy!

A few finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial north of) the midway point along the line joining Matar to Eta Peg, you’ll find a particularly busy assortment of galaxies! The Deer Lick Group is composed of the large, magnitude 9.48 spiral galaxy named NGC 7331, plus a number of minor satellite galaxies, the “Fleas”. Although discovered in 1784 by William Herschel, the unusual name was apparently coined by astronomer Tomm Lorenzin, co-author of “1000+ The Amateur Astronomers’ Field Guide to Deep Sky Observing”, who observed it from Deer Lick Gap in the mountains of North Carolina.

Just half a degree below (south) of the Deer Lick you’ll find the tight little Stephan’s Quintet – a gravitationally bound set of five galaxies. Both sets will all appear together in the field of view of a large aperture telescope at low magnification.

Before you call it a night, take a moment to seek out the Andromeda Galaxy. It is climbing the northeastern evening sky. An all-night target, this large spiral galaxy, also designated Messier 31, is only 2.5 million light years away from us, and subtends an area of sky measuring 3 by 1 degrees – that’s six full moon diameters by two! Under dark skies, the galaxy can be seen with unaided eyes as a faint smudge located 1.4 fist diameters left (or 14 degrees to the northeast) of the square of Pegasus. The three westernmost stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen) – namely Caph, Shedar, and Navi, also conveniently form a triangle that points downwards towards Messier 31. Binoculars will reveal the galaxy better. In a telescope, use low magnification and look for M31’s two smaller companion galaxies, the foreground Messier 32 and more distant Messier 110.

Cepheus the King of the Pole

If you missed last week’s tour of the circumpolar constellation of Cepheus (the King) I posted it with photographs here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Tuesday, October 5 at 7:30 pm EDT, iREx – Institut de recherche sur les exoplanètes and McGill Space Institute (MSI) will present a free online YouTube program entitled An Evening with Webb: Canadian Astronomers Using the Next Great Space Telescope. It will feature four Canadian woman astronomers. Details are here.

On Wednesday afternoon, October 6 at 2 pm EDT, the Ontario Science Centre will live stream Ask an Astronaut with Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut Joshua Kutryk. Learn about Joshua’s education, training and his aspirations to explore outer space. Plus, discover more about Canada’s role in the upcoming NASA-led Artemis missions, which are sending humans back to the Moon. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 6 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include the Sky This Month, observing asteroidal occultations, and a star party experience. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 6 at 7 pm EDT, the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics will live stream a free talk by Kurahashi Neilson, an associate professor at Drexel University and the recipient of a CAREER award from the National Science Foundation. The topic is A New View of the Universe from the Earth’s South Pole. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, October 12 when we’ll cover multi-wavelength astronomy and the James Webb Space Telescope. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!