Moon Moves to Morning, Easy Evening Planets, and Celestial King Cepheus!

This image of the Iris Nebula in Cepheus was captured through a RASA 11-inch f/2.2 Astrograph telescope and a ZWO ASI294MC Pro CCD camera by Gary Colwell at the North Frontenac Dark Sky Preserve northeast of Toronto, Canada. It shows both the reflection nebulosity and the surrounding dark dusty regions. The image spans 1.5 degrees left-right, with celestial north to lower left.

Hello, late-September Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 26th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read titled 110 Things to See With a Telescope (in paperback and hardcover) is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers.

The moon will clear out of the evening sky this week, allowing us to see autumn’s deep sky treats, such as the King of the Pole, Cepheus. Meanwhile, the bright planets Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn will catch the eye in evening, and the ice giants Uranus and Neptune will beckon telescope-owners over night! Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will vacate the world’s evening skies during this week and next – allowing us to better see autumn’s deep sky delights after dinner. At the latitude of Toronto, the sun is now setting about 2 minutes earlier every night and rising 1 minute later at dawn – providing stargazers with 20 minutes of extra viewing time each week! Speaking of the sun – don’t forget to use your eclipse viewers and safe solar filters to see the sunspots that are currently crossing the sun’s disk. I frequently check www.spaceweather.com for the latest picture. Click the sun thumbnail image to embiggen it!

Tonight (Sunday) the 68%-illuminated, waning gibbous moon will rise among the stars of Taurus (the Bull) at about 10 pm local time. Early risers can see that same moon in the southern sky before dawn, near the bull’s bright, reddish star Aldebaran. Or, turn your gaze upwards in the morning daytime sky to see our planet’s partner shining prettily in the southwestern sky.

As the week winds on, the moon will rise later and linger longer into daytime morning. It’s perfectly safe to look at the moon in daytime with binoculars or telescopes, as long as you take care not to aim them anywhere near the sun. Parental supervision is a must for junior moon-gazers.

The moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 9:57 pm EDT on Tuesday (which corresponds to 01:57 Greenwich Mean Time on Wednesday, September 29). At third quarter our natural satellite always appears half-illuminated, on its western side – towards the pre-dawn sun. The name for this phase reflects the fact that the moon has completed three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measuring from the previous new moon. Also on Tuesday, the moon will be passing through the stars of Gemini (the Twins). Observers in eastern Asia and the western Pacific Ocean can see the moon while it passes just a few finger widths from the big Shoe-Buckle Cluster aka Messier 35, which sits near the toe-stars of Castor. (That meeting will occur in daytime for the Americas.)

On Wednesday morning from 4:54 to 5:52 am EDT, observers with tracking telescopes in the Great Lakes region can watch the moon pass in front of (or occult) a magnitude 11.5 asteroid named (22) Kalliope. The leading edge of the moon will cover Kalliope first. An hour later it will pop out from behind the moon’s dark limb. Be sure to start watching a few minutes before each of the times quoted.

The crescent moon will depart Gemini for Cancer (the Crab) on Friday morning. When the moon rises over the east-northeastern horizon during the wee hours, it will be positioned several finger widths above (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial northwest of) the large open star cluster known as the Beehive Cluster and Messier 44. By the time the sky begins to brighten before dawn, the scene will be higher and the moon’s orbital motion will have carried it slightly closer to the cluster. To better see the “bees”, hide the moon beyond the edge of your binoculars’ field of view.

The moon will finish this week in Leo (the Lion). On Saturday morning, the slim crescent of the old moon will temporarily become the heart of Leo when it shines between the bright stars Regulus (to the moon’s right) and Algieba (to its upper left). The stars that form the lion’s neck and head are arranged in a fist-sized curve that extends upward from Algieba. The rest of the beast will extend downwards to the lower left (or celestial east), ending at his tail star, Denebola.

The Planets

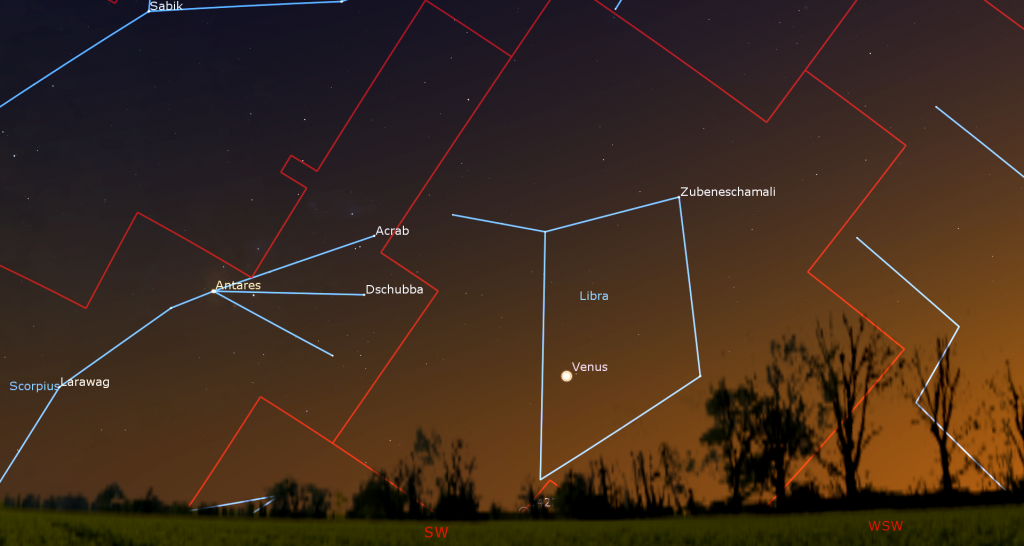

This week, extremely bright Venus will emerge from the post-sunset twilight shortly after 7 pm local time and then set by 8:30 pm. Venus will not be much higher than the trees and rooftops, so you might need to walk around until you find an open view to the west-southwest. Because the inner planets Mercury and Venus are closer to the sun than Earth, they show phases – just like the moon! When viewed in a backyard telescope Venus will exhibit a small, featureless, football-shaped disk because it’s only 63%-illuminated right now. It will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view.

While Venus descends the darkening west-southwestern sky, one-third as bright Jupiter will be about the same height in the southeastern sky. By 7:30 pm local time, the yellowish dot of Saturn should also become visible shining less than two fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right (or 16° to the celestial west). The two gas giants will cross the night sky together amidst the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and then set in the southwest during the wee hours. Sadly, for telescope owners, the low position of the ecliptic on September evenings is keeping those planets in the lower third of the sky, where their light must punch through two to three times as much of Earth’s distorting atmosphere – reducing their crispness. They’ll both look their best at about 10 pm local time, when they’ll be at their highest, 27° up in the southern sky.

Saturn’s thrilling rings are visible in any size of telescope. (Even good quality binoculars can show it as a oval shaped dot!) If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the outer and inner rings. Look for a faint dark belt encircling the planet, too. Take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. Much fainter Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other, so it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn, and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn (as it is this week). The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower left (celestial southeast) of Saturn tonight to the upper right (celestial northwest) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always appear to be strung like beads strung in a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line tilts as Jupiter crosses the sky, and the moons’ arrangement varies from night to night.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter on Monday and Wednesday after dusk, and in late evening tonight (Sunday) and Friday. It can also be observed during the wee hours of Wednesday and Friday morning.

From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Io’s small shadow will cross from 8:25 to 10:35 pm EDT on Monday night.

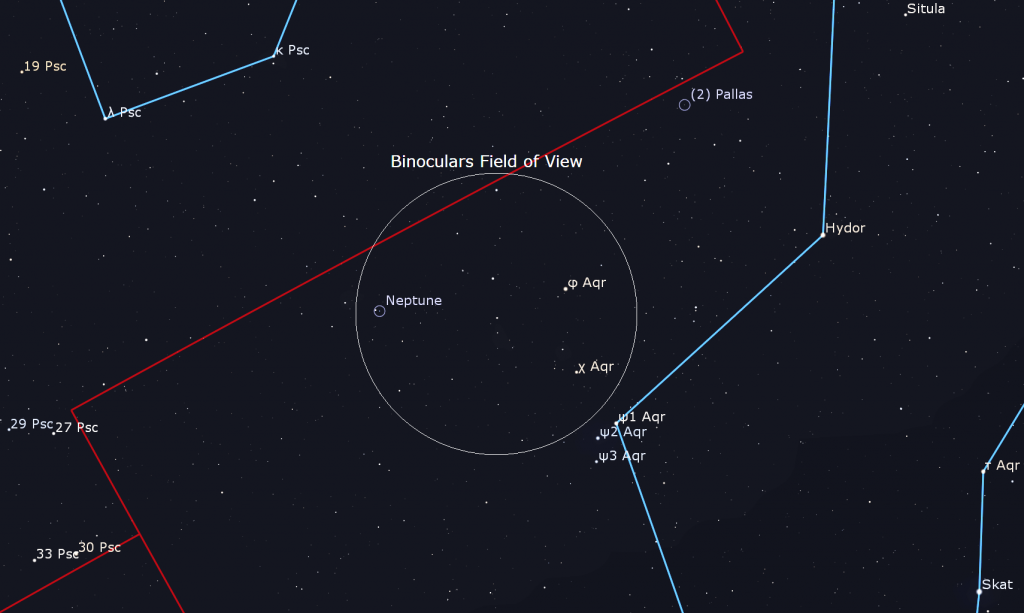

Distant, blue Neptune is in the all-night sky, near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes) – roughly three fist diameters to the left (or celestial east) of Jupiter. This moonless week will be a good time to observe the magnitude 7.8 planet. To help you find it, use binoculars to locate the up-down grouping of medium-bright stars Psi, Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). The little blue dot of Neptune will sit several finger widths to the left (or 4 degrees to the celestial NNE) of the top star, Phi. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is near those stars, too – on the right-hand (western) side. It’s still shining at close to peak brightness for 2021.

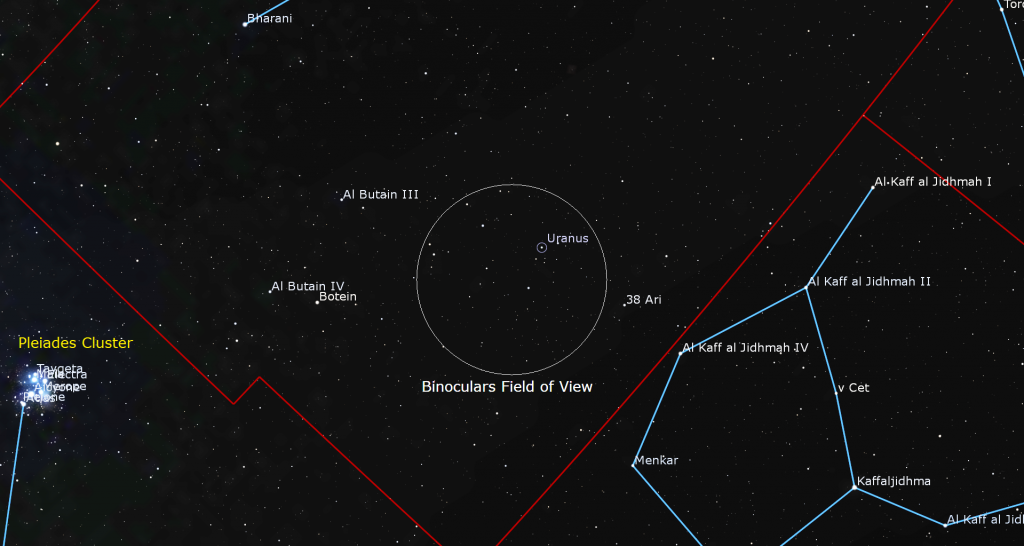

This week Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be observable nearly all night after it rises around 8:30 pm local time – but wait until it has climbed higher in late evening to view it. Uranus is spending all of this year parked below Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram). It’s about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial WSW) of the Pleiades star cluster. The blue-green planet is currently surrounded by the moderately bright (5th magnitude) stars Sigma, Omicron, Rho, and Pi Arietis – creating a distinctive asterism for anyone viewing Uranus in binoculars. This is a good week to seek it out, since the bright moon will be gone.

Cepheus the King

For observers living at mid-northern latitudes around the world, the constellations that circle the north celestial pole stay above the horizon at all times – day and night. But that doesn’t mean they are always visible. The circumpolar Big Dipper is part of the large constellation Ursa Major (the Big Bear). During evening in autumn every year, Ursa Major sits so low over the northwestern horizon that the stars of the famous dipper are often hidden behind buildings or trees. Six months later, that constellation is nearly overhead during evening – the best position for exploring its deep sky treats.

From September to December, the circumpolar constellation of Cepheus (the King) sits nice and high in the northern sky during evening, perfectly positioned for viewing – and it contains some fascinating sights because it’s located close to the Milky Way. Let’s explore the king of the North Pole!

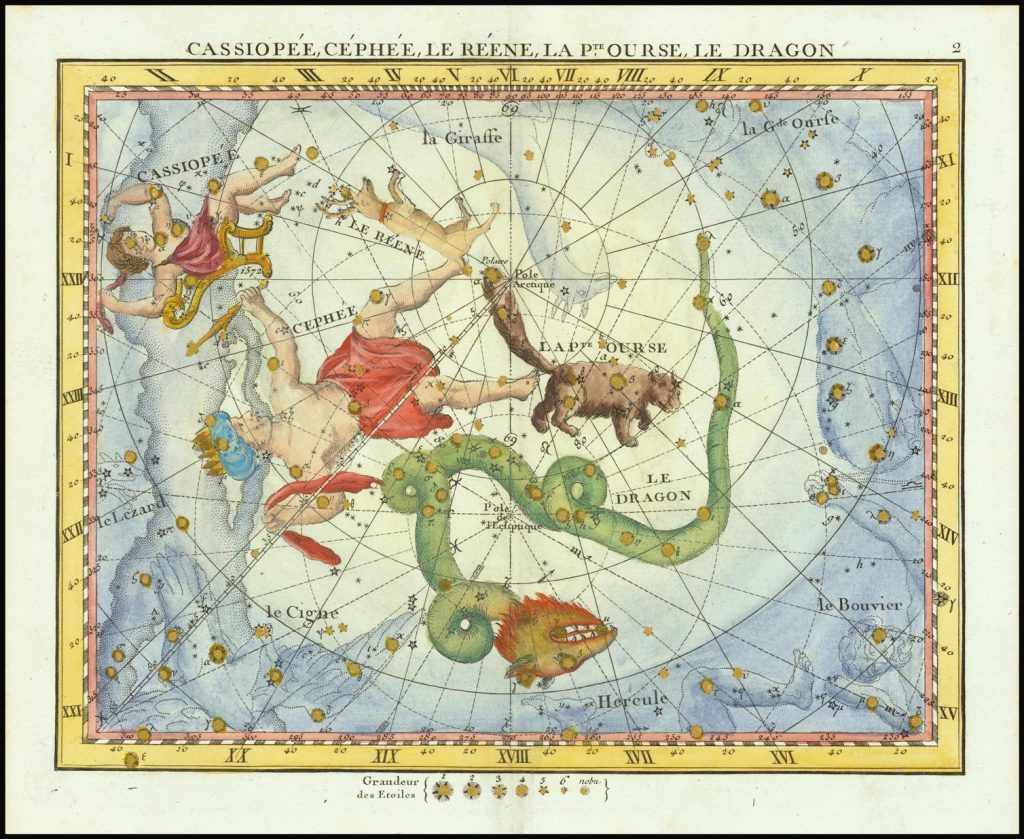

In Greek mythology, Cepheus was the king of ancient Ethiopia. He was married to Queen Cassiopeia. Their daughter Andromeda was the princess who was rescued by the hero Perseus, astride his winged horse Pegasus. Each of those characters is represented by a constellation in the northeastern sky during autumn. I’ll relate their tale in a future Skylights. In Arabic tradition, Cepheus was named Al-Multaheb. In ancient China, the stars of Cepheus were divided amongst the Black Tortoise of the North (北方玄武, Běi Fāng Xuán Wǔ) and the Three Enclosures (三垣, Sān Yuán), part of the Heavenly Purple Palace that occupies the region around Polaris. Other ancient cultures incorporated Cepheus’ brightest star, Alderamin, into their own star pictures.

For those of us who have been using the three bright stars of the Summer Triangle to navigate the sky, Cepheus is easy to find. Just face southwest and extend the line joining Altair to Deneb upward by about two fist diameters. I prefer to view him by facing north – in which case he’ll be located about two fist diameters directly above Polaris at 10 pm local time. For observers living in the tropics, this is only time of year when Cepheus is visible, low over the northern horizon in evening.

In form, Cepheus is little more than a triangle affixed to one edge of a square – like a crooked house with a tall pointed roof. From classical star atlases, the peak of the roof marks the king’s feet, and the stars forming the base of the house mark his head and shoulders. Because he circles the pole, you might see him right-way up, upside-down, or sideways – depending on the time of year and time of night. This month, he’ll be head-up and feet-down during evening – but the “house shape” will be oriented so the roof points down.

The brighter stars of Cepheus span or 21° (about two fist widths) of sky from his toes to his crown by 9°, the width of his hips and shoulders – but the constellation’s territory is twice both of those dimensions. It extends from Polaris southward – between Cassiopeia and Draco (the Dragon) – to the borders of Cygnus (the Swan) and Lacerta (the Lizard). Viewed while facing north, the bright, W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia is to the king’s right (celestial west), and the curved neck of the dragon is on his left (east). Bright Deneb sits high over his left shoulder, and the lizard is creeping downwards towards his right shoulder – although he seems to fending it off with an upraised staff. Some star maps connect a pair of stars to his left shoulder – as if his arm is extended.

Cepheus’ brightest star is magnitude 2.45 Alderamin, from the Arabic expression for “the Right Arm”. (Since he’s facing you, his right is on your left.) Bright enough to see even in light-polluted skies, Alderamin is a white, A-class star located about 49 light-years from our solar system. It’s somewhat hotter than our sun and about twice the size. It also appears to have a very high rotation rate of 12 hours, versus our own sun’s 27 days!

Eta Cephei (or Kebalfird or η Cep), the medium-bright star sitting about four finger widths to the left of Alderamin, marks the king’s elbow. A dimmer star designated Theta Cephei (or θ Cep) sits two finger widths to the lower left of Eta. It marks the king’s right hand.

Starting back at Alderamin, look a bit less than a fist’s diameter below, and slightly to the right of it, for a moderately bright star named Alfirk (“the Flock”) or Beta Cephei (or β Cep). Alfirk, which marks the king’s hip, is a pulsating variable star located 690 light-years away from us! This hot, blue-white star is more than ten times the mass of our sun, and has at least two companion stars that are too close to it to see visually. The star varies slightly in brightness every 4 hours and 34 minutes, due to the effects of iron enrichment in the star’s interior.

Errai (“the Shepherd”), also designated Gamma Cephei (or γ Cep), sits a generous fist diameter to the lower right of Alfirk – at the “peak of the house’s roof”. It’s an orange, K-class star that shines as brightly as Alfirk – although it is only 44 light-years away from us. This star, which marks the king’s feet, is a binary star system that includes a faint, red dwarf star. In 1988 Canadian astronomers detected the signal of an extra-solar planet around Errai. It would have been the first one confirmed – but their data wasn’t definitive enough. That honour went to the star 51 Pegasi a few years later. Newer, better data confirmed Errai’s planet in 2002, now named Tadmor – the ancient Semitic name for the city of Palmyra in Syria.

The star Iota Cephei (or i Cep) completes the triangle of lower Cepheus. That orange-tinted, K-class star shines about as brightly as Errai below it and Alfirk to its left. A fist’s diameter above Iota, and a generous palm’s width to the upper right of Alderamin, is Zeta Cephei (or ζ Cep). It’s another orange giant star that shines at magnitude 3.35, about the same brightness as the other corner stars.

A little star named Epsilon Cephei (or ε Cep) sits just a finger’s width above Zeta. It shines at a modest magnitude 4.2, about half as bright as Zeta. But the really interesting star is the one located about two finger widths to Zeta’s lower right. That’s Delta Cephei (or δ Cep). Delta Cephei varies in brightness by more than a factor of two every 5 days and 9 hours. At its peak, it’s as bright as Zeta. At its minimum, it’s as bright as Epsilon. So you can tell at a glance which part of its cycle it’s in! Delta is also a nice double star when viewed in telescopes – splitting into a brighter yellow star and a dimmer blue star.

Delta Cephei is a giant, pulsating supergiant star located about 900 light-years from our sun. Its variability occurs because it has consumed its core hydrogen, and it is entering old age. There are many of these stars in the sky – including Polaris! They are now known as Cepheid variable stars. In 1912, Henrietta Swan Leavitt of Harvard discovered that the time they take to cycle in brightness (their period) relates directly to their maximum brightness. Knowing that, she and other astronomers have been able to use them as “Standard Candles” to measure distances in the Universe, as follows: Find a Cepheid-type variable, measure its period, calculate its expected maximum brightness, and compare how bright it is with how bright it looks. (It’s similar to estimating how far away a motorcycle is at night by how bright its headlight appears.) Cepheid variables have been used to estimate the size of our Milky Way, and to work out the distances of other galaxies, like the Andromeda Galaxy.

Our last stop in the tour of Cepheus’ stars is Mu Cephei (or μ Cep), also known as Herschel’s Garnet Star. It’s one of my favorite objects. It’s located midway between Alderamin and Zeta Cephei, and just above the line connecting those two stars. You can see it with unaided eyes in a dark sky. And that’s amazing because this star is a whopping 2400 light-years away from us! (Actually, we’re not that sure about the distance – it could be farther.)

Mu Cephei is visible at such a distance because it is huge – about 1400 times the size of our sun. If it traded places with our star, the orbits of all the planets out to Jupiter would be inside the star! What makes it truly amazing to look at is the colour. It’s among the reddest bright stars in the sky. It’s an M-class star nearing the end of its life – similar to the much closer-to-Earth Betelgeuse in Orion (the Hunter). One day it will explode in a supernova.

I’ll devote a future story to the deep sky objects in Cepheus – but you will certainly see rich star fields, star clusters, and nebulas if you sweep the constellation with binoculars or a backyard telescope. For example, Mu Cephei is on the northern edge of a great cloud of pink hydrogen gas known as the Elephant’s Trunk Nebula. It’s four times the width of the full moon, and it will extend upward from Mu Cephei during September evenings. Other smaller nebulas include the Wizard Nebula (NGC 7380) near Delta Cephei, and the Iris Nebula (NGC 7023) near Alfirk.

There is an open star cluster between Zeta and Delta (NGC 7261), another two finger widths to the upper left of Eta Cephei (NGC 6939), and one more in the centre of the large square, near the king’s heart called the Swimming Alligator Cluster (NGC 7160). Way down near Polaris is the Polarissima Star Cluster (NGC 188). That dense cluster of small stars is half the width of the full moon, and is object number 1 in the Caldwell list.

As a final thought – Cepheus is truly the king of the North Pole. Errai will replace Polaris as Earth’s pole star around 4000 AD. Alfirk will take that honour around 6500 AD. And then Alderamin will take over in 7500 AD! Let me know how your audience with the king goes!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns this Tuesday, September 28 when we’ll cover the life cycle of our sun and other stars, including examples that you can see yourself on an autumn evening. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday, September 29 at 7:30 pm EDT, the Arthur B. McDonald Canadian Astroparticle Physics Research Institute at Queen’s University will present the free, online 2021 Harold M. Cave Memorial Lecture, featuring the terrific author Dava Sobel. Her talk is titled Women’s Work at the Dawn of Astrophysics. Details and the Eventbrite registration link are here.

On Thursday, September 30 at 7 pm EDT, local science outreach superstars Misha Gajewski and Sara Mazrouei will host The Story Collider: Toronto’s Online Story Hour – Indigenous in STEM. The free online program will feature three indigenous storytellers: Hilding Neilson, an astronomer at the University of Toronto; Yotakahron Jonathan, a Mohawk, Bear clan woman from Six Nations of the Grand River; and Taylor Morriseau (Cree/English, Peguis First Nation), a PhD Candidate at the University of Manitoba in the Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Details and links are here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!