Bright Moon Minors a Major Meteor Shower, Saturn Stuns, and Jupiter Sports Spots!

A detailed map of the lunar region around Copernicus, which is best viewed as the moon is within several days of full. (Stellarium)

Hello, August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 7th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will brighten skies worldwide this week as it becomes the fourth and final supermoon of 2022 when full on Thursday night. Unfortunately that moonlight will hamper views of the fantastic Perseids Meteor Shower that peaks on Friday-Saturday. As compensation, the planets are brightening and moving into evening, with Saturn peaking at opposition next Sunday and Jupiter sporting both the Great Red Spot and moon shadow transits. Read on for your Skylights!

Perseids Meteor Shower

The annual Perseids Meteor Shower is the one I look forward to the most. While December’s Geminids and January’s Quadrantids deliver more meteors per hour at their peaks (150 and 120, respectively), cloudy winter skies and bitter cold aren’t conducive to enjoying their displays. The Perseids shower, on the other hand, delivers 60 to 100 meteors per hour at its mid-August peak, which always arrives during the hot, dry part of summer at mid-northern latitudes. Perseids are famous for manifesting as bright, sputtering fireballs! Some leave “smoke trails” that dissipate in a few minutes. My friend Blake Nancarrow has prepared a very informative chart here that shows meteor shower counts throughout the year.

Unfortunately, moonlight obscures meteors by brightening the sky. For 2022, the Perseids shower will peak a day after the full moon, which will contaminate the night sky from dusk to dawn, and let only the fewer, brightest meteors stand out. (In 2023, we’ll be back to moonless sky conditions for the shower – so plan to holiday at a dark-sky site around August 12-13.)

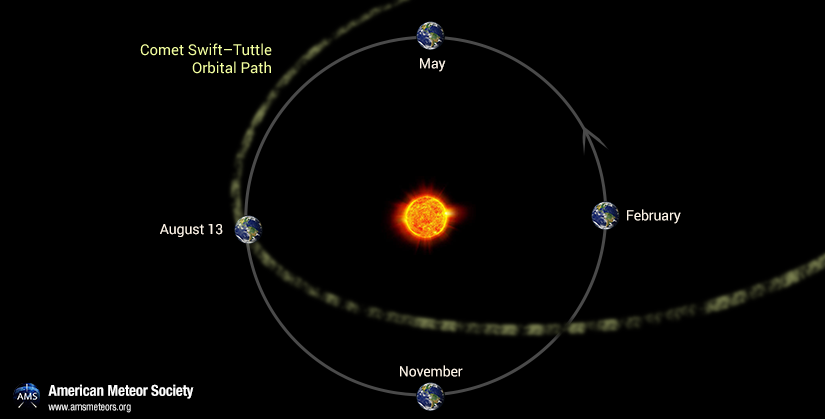

Meteor showers are events that re-occur on the same dates every year when the Earth’s orbit carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. (The analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty after the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over time, the dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into an elongated, tube-shaped cloud in interplanetary space. The source of the Perseids material is thought to be a large, 133-year-period comet named 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which was discovered by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862. When it last passed Earth in 1992, it wasn’t visible – but astronomers predict that its 2126 pass could be spectacular! Here’s a link to a fun 3D model of the comet’s path through the solar system.

When the Earth plows through the debris cloud, the particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air along its path – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud in space and the angle that we intersect it, i.e., how long Earth takes to pass through it. The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion of the debris field, or merely skirt the edges. Due to small variations in orbits any shower’s performance can vary from year to year, independent of the moon.

While visible anywhere in the night sky, meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The radiant for the Perseids sits in northern Perseus (the Hero) – near its brightest star Mirfak and that constellation’s border with Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). Meteor showers are strongest before dawn because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant is overhead, the entire sky down to the horizon is available for meteors. When it’s low, many of the meteors are hidden below the horizon. The Perseids’ radiant is low in the northeastern sky during mid-August evenings – and nearly overhead by dawn.

The active period for the Perseids shower is July 13 through August 26, ramping up towards the peak night and then tapering off. This year, you might be better off watching for Perseids before dawn on Wednesday or Thursday morning because the bright moon will be setting early. On the mornings after the peak, though, the moon will stick around past sunrise. Plan your viewing with an eye to the weather forecast. It’s better to see fewer Perseids on a clear night, than to not see any if it’s cloudy on the Friday-Saturday peak.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place about 100 km over your head and within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

To see the most meteors, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky is dark. That’s a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors in that part of the sky will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. When you see a meteor, try to trace its path backwards to see if it points to Perseus. Some of them won’t!

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use it, turn the brightness down, or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes have will not help you see meteors.

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, caused by the Earth passing through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic Comet 96P/Machholtz, will be tapering off until August 23. Those meteors will appear to travel away from that shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), which sits in low in the southeastern sky during evening. Good luck!

The Moon

Evenings during the first half of this week will continue to deliver terrific opportunities to see the moon’s terrain dramatically lit by slanted sunlight along the terminator – in binoculars or through any size of telescope. Today (Sunday) the waxing gibbous moon will rise in late afternoon and cross the daylit sky as a pale orb. When dusk arrives, the main stars of Scorpius will appear around the bright moon – particularly the bright, reddish star Antares twinkling a fist’s diameter to its right (or celestial west). Sunday night will be a great time to see the Golden Handle of Sinus Iridum that I described last week here.

On Monday and Tuesday night, the fuller moon will rise an hour later and hop from right to left of the teapot-shaped star pattern of Sagittarius (the Archer). On Wednesday the 98%-illuminated moon will rise shortly after sunset, shining to the right (or celestial west) of the faint constellation of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), while the creamy dot of Saturn accompanies that critter’s tail stars on the left.

The August full moon will officially occur on Thursday at 9:36 pm EDT and 6:36 pm PDT, which converts to Friday at 01:36 Greenwich Mean Time. This full moon, colloquially called the “Sturgeon Moon”, “Black Cherries Moon”, “Green Corn Moon”, and “Grain Moon”, always shines among or near the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) or Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The indigenous Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Manoominike-giizis, the Wild Rice Moon, or Miine Giizis, the Blueberry Moon. The Cree Nation of central USA and Canada call it Ohpahowipîsim, the Flying Up Moon. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of Eastern North America use Seskéha, the Freshness Moon.

The moon becomes fully illuminated when it is opposite the sun in the sky, causing the moon to rise at sunset and set at sunrise. Observers sharing longitudes with the eastern half of North America will see that scenario play out. Elsewhere on Earth, the moon will be slightly less or slightly past full when it rises. Magnified views will reveal a thin strip of darkness along the moon’s western or eastern limb. Since the sun is high in daytime during summer, full moons are low in the night sky. The reverse happens in winter.

Since this full moon will occur less than two days after perigee, the moon’s minimum distance from Earth, this will be the fourth and final supermoon of 2022. Since there are no shadows being cast by topographic features on a full moon, all the brightness variations are attributable to differences in lunar rocks. Watch for lighter and darker sections within the dark lunar maria, produced when basalts of different chemical composition flooded them across time. And seek out the many streaks surrounding the fresher craters – rays of ejected material.

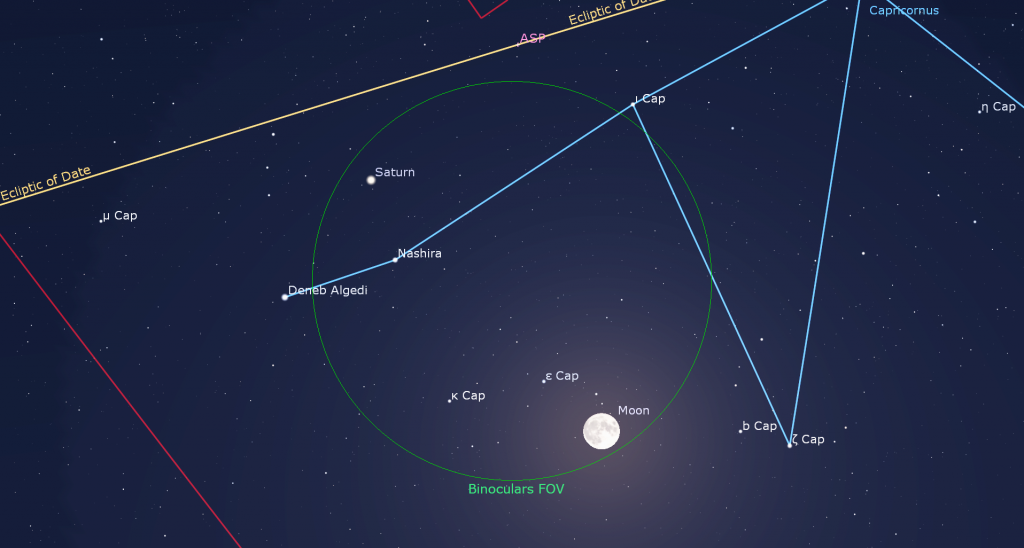

Thursday night’s moon will also be shining a slim palm’s width to the lower right (or 5 degrees to the celestial south) of a triangle of bright stars. The brightest and highest of the trio will be Saturn. The moon and Saturn will be cosy enough to share the view in binoculars. The grouping will cross the night sky together. As they do so, the diurnal motion of the sky will shift the moon to below Saturn around midnight, and then to Saturn’s left as they prepare to set in the west-southwest toward sunrise. (Saturn will remain part of that triangle on the following nights.)

From Friday to Saturday the bright, waning gibbous moon will travel across the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). By then its late rise time will see it linger into the southwestern morning sky.

The moon will sneak up on very bright Jupiter in Cetus (the Whale) on Sunday night – just close enough to be viewed together in binoculars. If you pay attention them, you’ll see the moon shift closer to the planet as revolve partway around it as the hours tick by.

The Planets

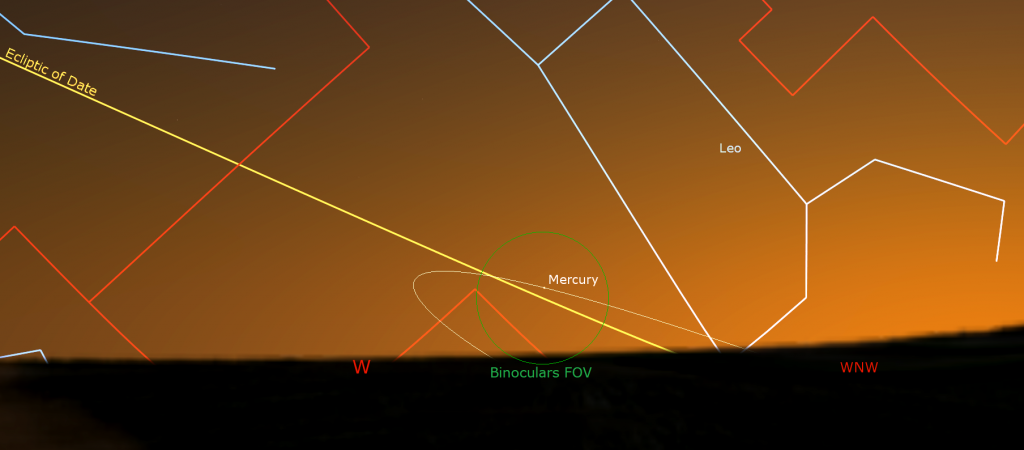

All eight planets will continue to be visible from dusk to dawn this week. Elusive Mercury will continue to swing away from the sun in the western sky after sunset. Although its greater angle from the sun would normally make it easier to see with each passing night, the low angle of the ecliptic will hold the planet very low in the sky for mid-northern latitude observers. Mercury’s show during August will be the best of the year if you live in the tropics or the Southern Hemisphere, where it will sink in a darker sky above where the sun sets.

For the rest of us, look for Mercury shining a few finger widths above the west-northwestern horizon, and less than a palm’s width to the left of where the sun sinks out of sight. Once the sun has completely disappeared, it’s safe to use binoculars for your search. The prime viewing window will fall around 9 pm local time. On each consecutive night, Mercury will shift to the left, farther from the sunset point. You’ll need a cloud-free, haze-free horizon to see it.

Saturn’s medium-bright, yellowish dot will already be shining just above the southeastern horizon by 9:30 pm local time, and then it will cross the lower part of the sky during the night (due south around 2 am local time and above the west-southwestern horizon at sunrise). This year Saturn is shining among the faintish stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). As I mentioned above, two small stars can be seen below Saturn. Those are Deneb Algedi on the left (east) and Nashira on the right (west). They represent the tail of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more to the right (or celestial west) above those stars over the next few weeks. Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the distant planets and asteroids “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars.

Saturn will have climbed high enough for reasonable telescope views by 10 pm – and this is the week to view it! On Sunday, August 14, Saturn will reach opposition for 2022. Objects at opposition are visible all night long – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise – because Earth is positioned between them and the sun. At opposition, Saturn will be at a distance of 1.325 billion km or 73.7 light-minutes from Earth, and it will shine at magnitude of 0.28 – its brightest for the year. While planets at opposition always look their brightest, Saturn will be intensified by the Seeliger effect, backscattered sunlight from its rings.

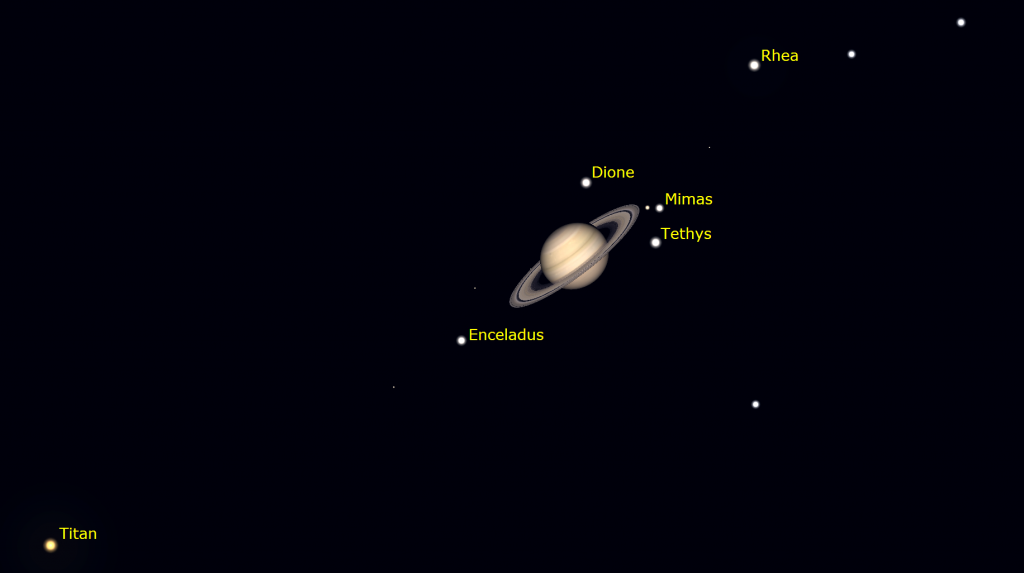

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s apparent disk diameter of 18.8 arc-seconds, and its 43.7 arc-seconds-wide rings. Saturn’s rings will become more edge-on to us every year until the spring of 2025. This year they have closed enough for Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond them. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

A small telescope will also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower left (celestial east) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the upper right (celestial west) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

The main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta is currently positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 12.6° to its celestial east-southeast). Vesta’s fairly bright, magnitude 5.9 dot is observable in binoculars and small telescopes – especially during the wee hours, when it has climbed highest in the sky. Look for Vesta a palm’s width to the right (or 6 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the medium-bright stars Skat (aka Delta Aquarii) and Tau Aquarii. Telescope owners should note that Vesta will be travelling just a few degrees to the upper left (or 2.5° to the celestial north) of the spectacular, but faint Helix Nebula, also known as NGC 7293. They’ll be closest next week.

This week, extremely bright Jupiter will appear over the eastern horizon shortly after 11 pm local time, and then spend the night following fainter Saturn across the sky. Jupiter will climb high enough to look good in a telescope from about midnight local time onward. Early risers can spot the planet halfway up the southern sky just before sunrise. Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons, which dance about the planet. If you see fewer than four, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow, or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

For observers in the Americas, the Great Red Spot will cross Jupiter’s disk late on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday night, and also during the wee hours of Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. On Monday night, August 8, telescope-owners viewing from northeastern North America and across to central Europe and Africa can watch the small black shadows of two of Jupiter’s moons cross the planet’s disk at the same time! At 9:34 pm Atlantic Daylight Time, which converts to 00:34 GMT on August 9, Europa’s small shadow will join Ganymede’s large shadow already crossing. The two shadows will appear together for 80 minutes until Ganymede’s shadow moves off the planet at 11 pm ADT, or 02:00 GMT, leaving Europa’s shadow to complete its transit at 11:44 pm ADT or 02:44 GMT. Observers in the Eastern Time Zone will barely have time to see those shadows finish crossing after Jupiter rises. The small round, black shadow of Europa will cross Jupiter’s disk on Saturday morning from 12:45 am to 3:15 am EDT.

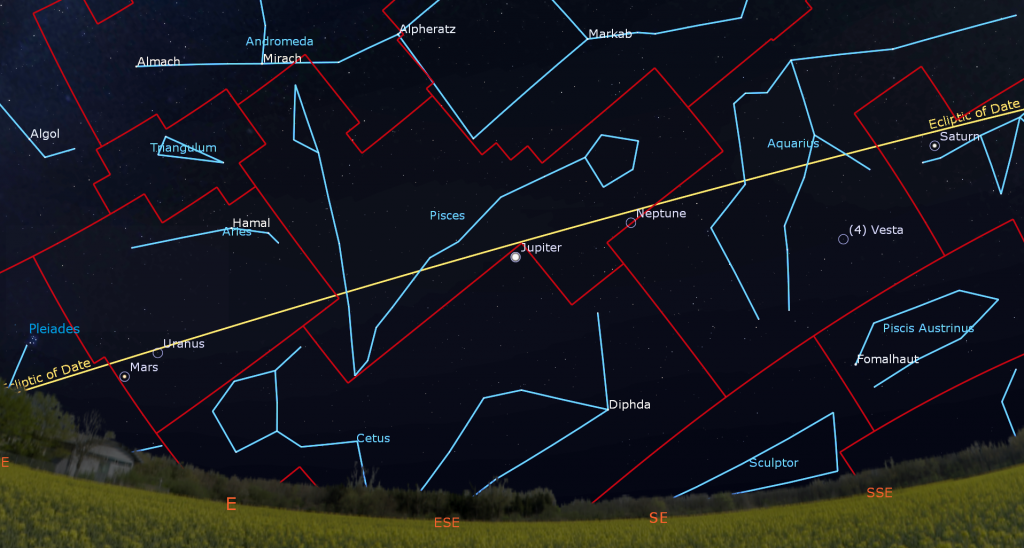

The faint blue speck of Neptune will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right, and a thumb’s width to the upper right (or 1.4° to the celestial west) of a small star named 20 Piscium, which sits on the line joining Jupiter to Saturn. Neptune has a large moon named Triton that is visible in large aperture telescopes, especially during the next couple of months when we’re closer to the planet.

Medium-bright, reddish Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon by 12:30 am local time and will clear the eastern rooftops, along with the Pleiades star cluster, about an hour later. Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit gradually draws us closer to it over the coming months. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. Mars recently passed close to Uranus. Today (Sunday), magnitude 5.76 Uranus will be shining a few finger widths to the upper right (or 4° to the celestial west) of Mars – but Mars is speeding away eastward. You’ll be able to fit both of them at once into binoculars only until about Thursday. Without Mars to help you, the brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis), which will appear several finger widths to Uranus’ left (or 3° to the celestial northeast). Uranus will be easiest to see when it’s higher in the sky, in the hours before dawn.

Extremely bright Venus will rise in the east at about 4:30 am local time this week – but it won’t climb very high before sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. The planet is slowly shifting closer to the sun. Venus will exhibit a waxing, nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. Early risers can look for the two bright stars Castor and Pollux shining above the planet, and the tilted form of Orion (the Hunter) off to their right.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Weather permitting, on Tuesday, August 9 from 8:30 to 10 pm, astronomers from RASC – Mississauga will hold a public star party at the Riverwood Conservancy, 4300 Riverwood Park Lane, Mississauga. Details and the ticket registration link are here.

On Thursday evening, August 11 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Hamilton Centre will live stream their Speaker Night Meeting on Zoom. The presenter is Professor Brad Gibson, Head of the Department of Physics & Mathematics, and Director of the E.A. Milne Centre for Astrophysics, at the University of Hull in England, presenting Liquid Mirror Telescopes: Wave of the Future (or just a ripple…?). Details and the Zoom link are here.

RASC’s Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Saturday night, August 13 from 9 to 10:30 pm EDT, the DDO Up in the Sky program will feature a Perseids Meteor Shower Special, in collaboration with York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory. There will also be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday August 10, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, August 14 from 11 am to noon EDT, join me for DDO Ask an Astronomer. During the family-friendly session, I’ll answer your questions about the universe and review what’s up nowadays. The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, August 10, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 16 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the GTA this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!