Bright Stars Battle with the Full Sturgeon Supermoon While Mercury Mounts and Saturn Shines by Night!

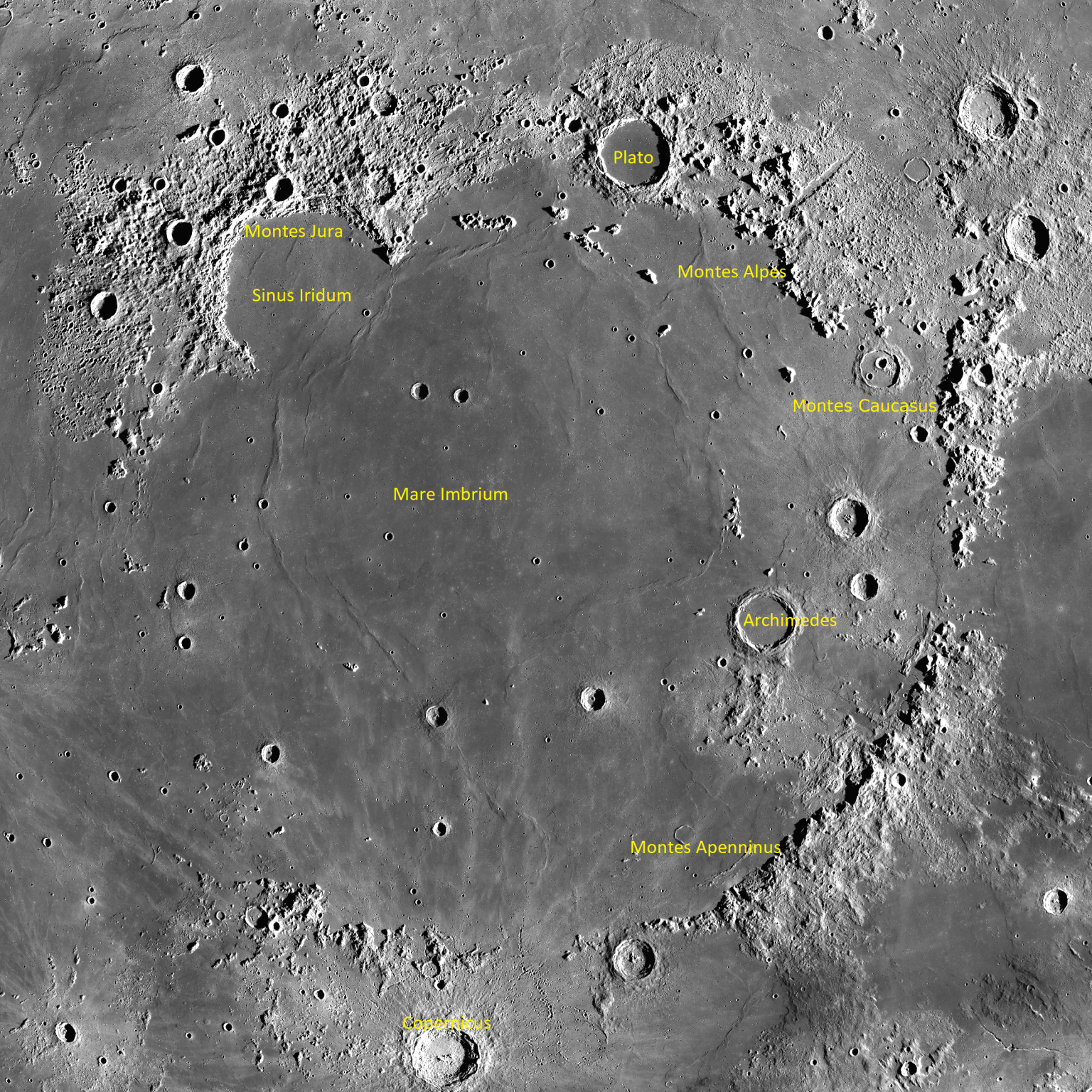

This Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter image shows the major features of Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Rains. Oceanus Procellarum mare material appears along the far left side of the image.

Welcome to August, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 30th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will dominate night skies worldwide for much of this week, especially when Tuesday’s largest supermoon of 2023 arrives. Later, the waning moon will visit Saturn and occult some stars in Aquarius. Mercury and faint Mars are lurking above the western horizon after sunset, Jupiter shines with Saturn overnight, and I tour you through some stars that are bright enough to withstand the moonlight. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will continue to dominate the overnight sky worldwide for most of this week. Even though sunset is arriving around 8:45 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes, our best stargazing time, when the stars grace a dark sky, doesn’t really begin until much later. The bright stars are twinkling overhead by 10 pm, but the minor celestial diamonds won’t be sparkling until almost 11 pm. Unfortunately for some, the moon will be rising at or soon after sunset and filling the overnight sky with bright moonlight every night until next weekend. Dark moonless skies for Milky Way and Perseids meteor shower lovers will return around August 8. In the meantime, there will be lots of moonlight for evening strolls since this week will deliver the first of two super full moons during August!

Today (Sunday) the moon will rise in the southeast a little while before the sun sets in the west. After dusk, the moon will be gleaming in the lower part of the sky inside the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). You might be able to see some of those stars if you block the bright, 95%-full moon with your thumb and close one eye, or use binoculars.

When the moon reaches its highest point in the sky, due south around midnight, it will only be a short distance above the horizon. While summer full moons are always low by virtue of being opposite the high noonday sun, this moon will be even lower. The moon’s orbit is inclined or tilted by 5° (almost a palm’s width) with respect to the ecliptic, and it ranges north and south of that imaginary circle while it rolls around Earth through each lunar month. It happens that this week the moon is at nearly its maximum distance below (or to the celestial south of) the ecliptic, further reducing its elevation.

On Sunday, the pole-to-pole lunar terminator will be westerly enough to allow the broad, grey expanse of Oceanus Procellarum, which spreads across much of the moon’s western Earth-facing hemisphere, to be bathed in sunlight. That “Ocean of Storms” covers about 4 million square km, equal to about the western half of Canada. Early in the moon’s history, a large object smashed into the moon at high speed, excavating a shallow bowl 3,000 km wide into the moon’s still-cooling crust. Later, dark, iron-enriched magma leaked out of the interior of the moon and flooded that basin with the grey rock we see today.

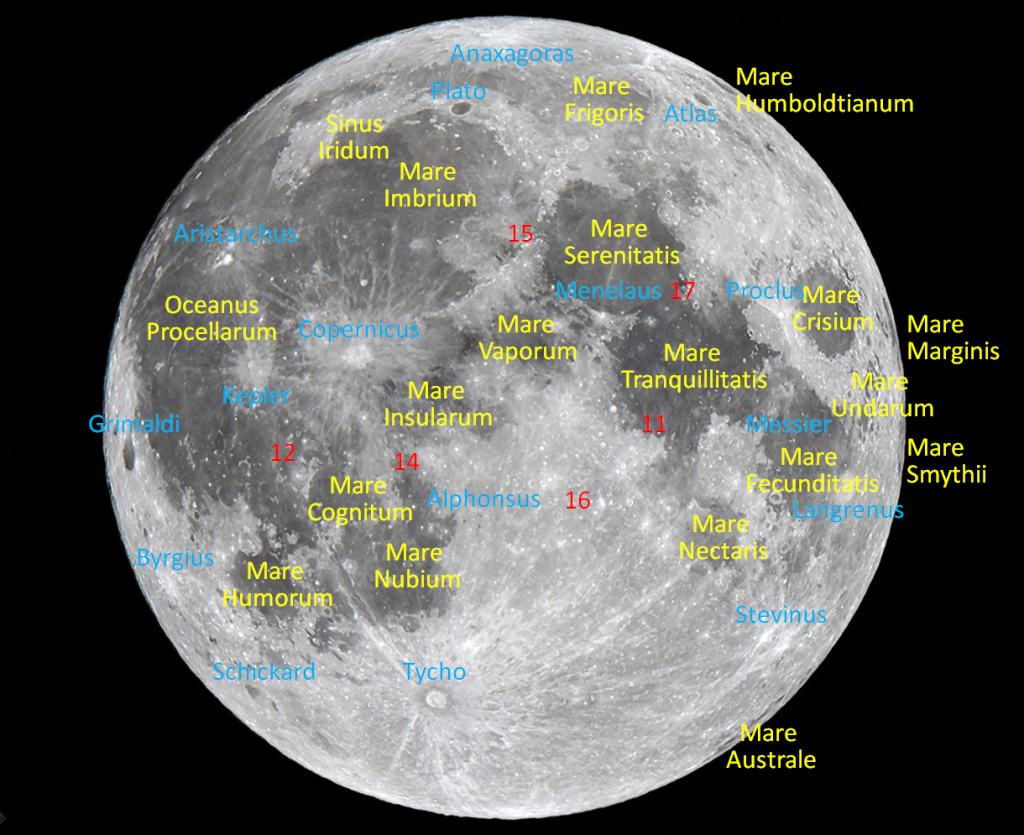

Early astronomers coined the term maria (Latin for “seas”) for the dark patches on the moon. Later, telescopes revealed that they were actually not wet at all! The very large, round, dark mare filling the northwestern part of the moon is Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Showers”. The maria to its south are patchy and interconnected. Mare Insularum “the Sea of Islands” is located directly south of it. Mare Cognitum “Sea that has Become Known” sits to its south. Small Mare Humorum “Sea of Moisture” and larger Mare Nubium “Sea of Clouds” are southernmost, to the left and right, respectively.

The terms maria and terra (the heavily cratered bright regions) were coined by Galileo Galilei after he began to view the moon in his little telescope starting in late 1609. The rest of the moon’s naming system was largely developed by Jesuit priest Giovanni Riccioli, who published a labeled moon map in 1651 that modern maps built upon. Riccioli used the names of living and dead scientists and philosophers for the craters, assigning ancient notables to the north of the moon and “modern” (to him, anyway) personages in the south. He placed teachers and their famous students together. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has continued that policy.

The maria are all named for weather and human states of mind, except for Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii, who were famous explorers, and for Mare Cognitum and Mare Moscoviense, which were discovered later on the moon’s far side. Fittingly, Riccioli placed the radical proponents of the heliocentric theory, the scientists Copernicus, Aristarchus, and Kepler, within the Ocean of Storms – and he honoured fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters. Grimaldi’s big, dark crater will be visible right along the moon’s terminator on Sunday night and then farther from it on Monday.

In the time since the basins were formed, several large (and many small) craters have been punched into them. The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. Copernicus’ 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around each full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts punched through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

Now, let’s get back to the moon-doings. On Monday and Tuesday night, the even fuller and brighter moon will be traversing the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) – but there’s little chance you’ll see those stars without binoculars.

For observers in the Western Hemisphere the moon will look full on Monday night – but about 1% of it along its western limb, will still be dark. That’s the left-hand edge for folks viewing the moon from the Northern Hemisphere, and the left-hand edge for southerners. Craters there will still cast shadows while the rest of the moon will look less dramatic under magnification. The moon only appears full when it is opposite the sun in the sky, so full moons always rise in the east as the sun is setting, and set in the west at sunrise. Since sunlight is hitting the moon face-on at that time, no shadows are cast. All of the variations in brightness you see arise from differences in the reflectivity, or albedo, of the lunar surface rocks, making the moon look less arresting under magnification.

The first of two full moons in August will occur on Tuesday, August 1 at 2:32 pm EDT, 11:32 am PDT, or 18:32 Greenwich Mean Time. When the moon rises hours later in the Americas, it will be already be starting to wane very slightly. Only observers at longitudes of the western Pacific Ocean will see it rise while it’s exactly full.

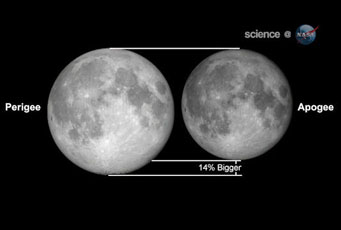

This full moon will occur only 9.5 hours before lunar perigee, the point in the moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth, making this a supermoon. Supermoons occur in consecutive groups or three or four – about every 14 months. During those periods, the moon’s 27.32-day sidereal orbital period that causes perigees and apogees temporarily synchs up with the 29.53-day synodic period that produces the moon’s phases. An astrologer named Richard Nolle appears to have coined the supermoon term in 1979, and has refined it since then. His “definition” requires that the moon be full while it is also within 90% of its closest approach to Earth – or within about 359,000 km. Supermoons look about 16% brighter and 7% larger than average. The world will experience higher perigean tides due to this full moon’s proximity to Earth. The August 30 full moon will be the largest supermoon of 2023, and the one on September 29 will be super, but slightly smaller.

The astronomical term for a supermoon is lunar perigee-syzygy, but unlike the media, astronomers don’t typically pay extra attention to the moon at that time. Don’t forget that any moon, even a supermoon, can easily be covered by a pinky fingernail held at arm’s length and one eye closed. That even applies to little children’s tiny fingers!

The August full moon, colloquially called the “Sturgeon Moon”, “Black Cherries Moon”, “Green Corn Moon”, and “Grain Moon”, always shines among or near the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) or Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The indigenous Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Manoominike-giizis, the Wild Rice Moon, or Miine Giizis, the Blueberry Moon. The Cree Nation of central USA and Canada call it Ohpahowipîsim, the Flying Up Moon. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of Eastern North America use Seskéha, the Freshness Moon.

After Tuesday night, the moon will wane in phase and rise about 30 minutes later each night. That half-hour increment will slow the moon’s departure from the evening sky. Grrr! On Wednesday it will shift east into Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). When the very bright, very full moon clears the rooftops in the southeastern sky in late evening, it will be shining a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of the bright, yellowish planet Saturn. While the duo won’t be cosy enough to share the view in binoculars initially, the moon’s steady eastward orbital motion, by about its own diameter every hour, will carry it closer to Saturn for those viewing them late at night or in westerly time zones.

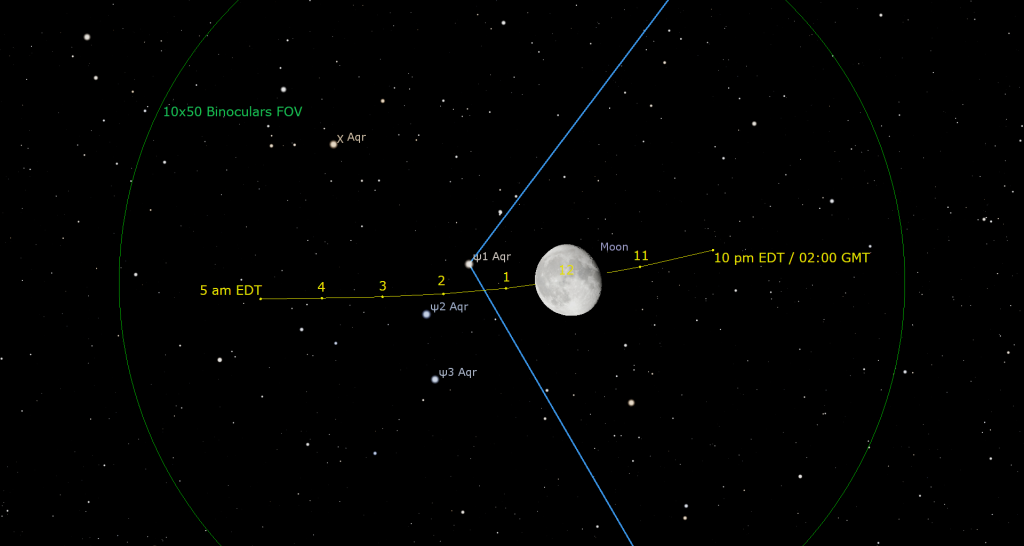

The group of three stars that mark the lip of the water-bearer’s tipping amphora have all been assigned the name Psi Aquarii, but astronomers use the numerals 1 to 3 to distinguish one from another. All three stars are bright enough to see with your unaided eyes when the bright moon isn’t nearby, or in binoculars and backyard telescopes. On Thursday night, August 3, observers in much of North America can watch the bright, waning gibbous moon pass in front of (or occult) in succession the higher (more westerly) stars of the trio.

The timing varies by location so use an app like Stellarium to look up the circumstances where you live. In Toronto the bright, leading limb of the moon will cover the star Psi1 at 1:10 a.m. and then Psi2 at 1:48 a.m. Eastern Time. Psi1 will emerge from behind the unlit, upper right edge of the moon at 1:55 a.m. EDT, while Psi2 will pop out from the lower right edge of the moon at 2:48 a.m. EDT. The moon will miss Psi3 altogether. For best results, use binoculars on a tripod or a backyard telescope and start to watch a few minutes before each predicted time. Watch for bright Saturn shining to the moon’s right (celestial west).

The waning moon will spend from Friday to next Sunday swimming along the crooked border between Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale). A while after the two-thirds lit moon clears the eastern treetops late on next Sunday night, the very bright planet Jupiter will appear to its lower left (or celestial northeast).

Sights for Moonlit Nights

While the bright moon ruins our views of summertime nebulas, stars can still entertain us – be they bright stars for unaided eyes or treats we see in binoculars.

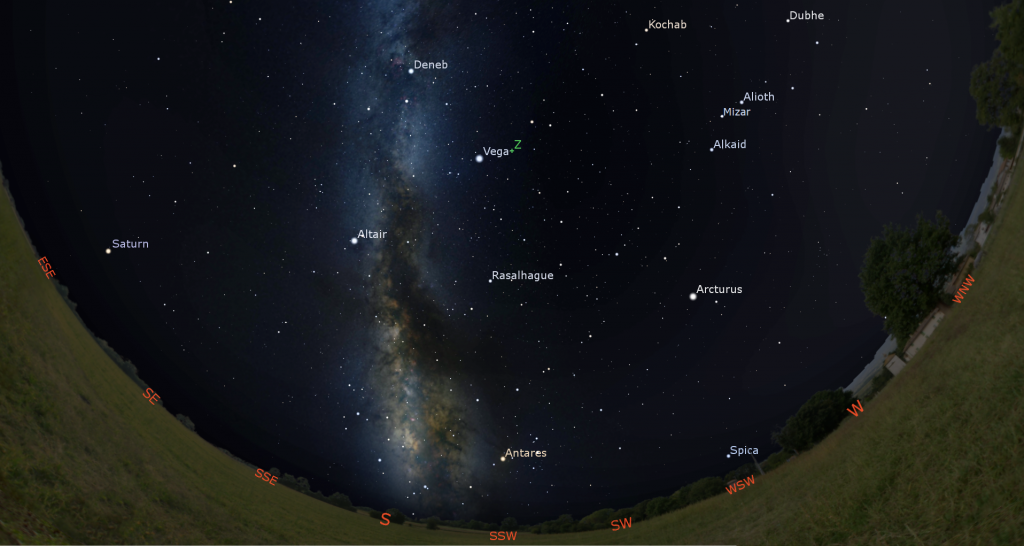

The first stars to appear on early-August evenings include the bright, white stars of the Summer Triangle. This asterism is an unofficial pattern formed using the brightest stars of three different constellations. (Anyone can make up their own asterism!) After dusk, the triangle is high in the eastern sky below the zenith. When you face east, Vega is topmost and first to appear. Less-brilliant Deneb sits two fist diameters to Vega’s lower left (or 23° to the celestial east). Altair sparkles three fist diameters to Vega’s lower right (or celestial south) – so the triangle is taller than wide. Despite its name, the asterism appears every summer and remains visible until the end of December!

At magnitude 0.03, Vega is the brightest star in the summer sky, mainly due to its relative proximity to the sun of only 25 light-years. Altair is only 17 light-years from the sun, but Deneb is a staggering 2,600 light-years away. It’s appears bright despite its greater distance because of its far greater inherent luminosity at visible wavelengths.

Keen eyes might reveal that the star Epsilon Lyrae, located just one finger’s width to the lower left (or celestial east) of Vega, is a double star. Binoculars or a small telescope will certainly show you two close-together stars. Examining Epsilon at even higher magnification will reveal that each of those stars is itself a double – hence its nick-name, “the double-double”. Epsilon Lyrae was given its name long before astronomers could see its extra stars using telescopes. The quartet, plus a fainter fifth companion star, are bound together by their mutual gravity, and are slowly orbiting one another in a “cosmic square dance”!

Stars shine with a colour that indicates their surface temperatures, and this is captured in their spectral classification. Our sun is a yellowish G-class star with a surface temperature of 5,800 K. The stars of the Summer Triangle are A-class stars that appear blue-white to the eye and have higher temperatures, in the range of 7,500 to 10,000 K. (Being massive balls of gas, stars don’t have a surface. But they do have a radius where they become opaque to visible light, effectively given them the appearance of having a spherical surface.)

The very bright and orange-tinted star Arcturus shines all evening long over in the western sky, in the kite-shaped constellation of Boötes (the Herdsman). Arcturus is a K-class giant star with a temperature of only 4,300 K. It was once whiter, but it has swelled up and cooled down in old age. Arcturus’ name is derived from Arabic for “follower of the bear”, referring to Ursa Major (the Big Bear). The Big Dipper asterism, made from part of Ursa Major, stretches across the northwestern sky during evening. The dipper’s curved handle “arcs to Arcturus”. Look closely at Mizar, the star where the dipper’s handle bends. A little star named Alcor is close to it. In a telescope, Mizar itself splits into a double star.

Reddish Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion), which sits low in the south-southwestern sky, is an old M-class star with a surface temperature of 3,500 K. If you stay up way past midnight, you’ll see bright yellowish Capella peeking over the northeastern horizon. It’s a sun-like G-class star located only 42 light-years away from us. By comparing these stars colours’ to other stars, you can estimate those stars’ temperatures. The classification letters, from hottest to coolest are: OBAFGKM. Can you think up a mnemonic phrase to remember the order? I’ll tell you mine when next we meet!

Here’s another trick to see star colours. Aim your telescope or binoculars at a star and unfocus the view so that the point-like star swells into a disk. You should be able to see that star’s colour better.

Meteor Shower Update

The annual Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, peaked last night, Saturday-Sunday, July 29-30, but it tends to be especially active for a week surrounding that date – so keep an eye to the sky for “shooting stars” early this week, despite the bright moon. The prolific Perseids meteor shower, which runs annually between July 17 and August 26, has begun, too! That shower will peak on the moonless night of August 12-13.

The Planets

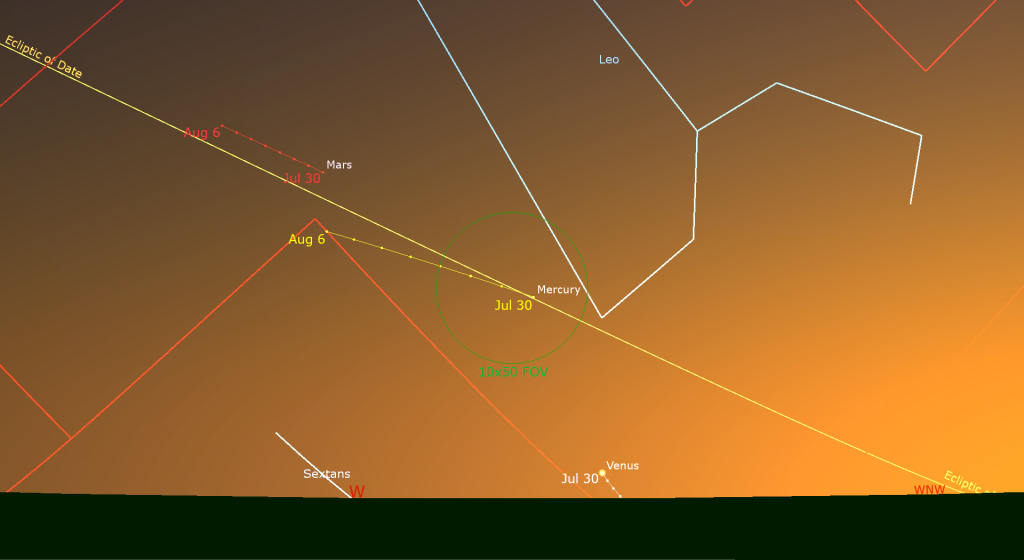

For observers at mid-northern latitudes around the world, Mercury will be the easiest planet to see after sunset this week. Brighter Venus will shine nearby, but it’ll be very low above the western horizon and obscured by twilight. Mars will be higher than Mercury, but very tough to spot due to its faintness. For the first few days of this week, all three planets will be fairly easy to see if you live south of about 30° N latitude, including the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere. But Venus’ daily descent sunward will hide it, even for viewers there, after mid-week. After passing well south of the sun in mid-August, Venus will return to grace the eastern pre-dawn sky in early September.

Mercury‘s easterly prograde motion through southern Leo will extend its distance from the sun and brighten the planet a little a bit more each night. Once the sun has set, look for Mercury’s dot positioned less a generous palm’s width above the west-northwestern horizon. The speedy planet’s current evening apparition will be the best one of the year for Southern Hemisphere observers, but its position just north of a very tilted evening ecliptic will keep the planet very low in the sky after sunset for mid-northerners – making this a lengthy, but poor quality showing for us. In a telescope, Mercury will show a waning, slightly gibbous phase.

Mars is moving eastward through Leo in the western sky, too – delaying its conjunction with the sun for a while yet. But its great distance from Earth (currently 2.4 times farther than the sun) has reduced its brightness to far below Mercury. You can try using binoculars to see its faint, reddish speck located about a fist’s width to the upper left (or celestial east) of Mercury. The two planets will cozy up a little next week.

This week, Saturn‘s yellowish dot will rise in the east-southeast at about 9:45 pm local time. It’ll climb high enough to clear the rooftops about an hour later – but the best time to view Saturn in a telescope will be between the wee hours and dawn, when it will be located a third of the way up the southern sky. If you head outside by about 5 am, you’ll still be able to see the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) shining around Saturn, and the bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars shining well off to its upper right. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn during this year.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from just below the planet (celestial south) on Monday morning (a very cool sight) to Saturn’s upper right (celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue planet Neptune, 600 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 21° to its celestial northeast.

Bright, white Jupiter, which shines about 16 times brighter than Saturn, will rise at about 12:20 am local time this week. Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. Jupiter will be easy to see until almost sunrise, when it will shine more than halfway up the southeastern sky. Jupiter will be rising in late evening from the second week of August onward, and will pose for after dinner star party views until March, 2024.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the east of Jupiter next Sunday morning.

Jupiter will climb high enough for good telescope views after about 1:30 am local time. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on early on Tuesday, Friday, and Sunday morning, and before dawn on Thursday and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Thursday morning, August 3, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 4:46 to 6:55 am EDT (or 08:46 to 10:55 GMT), though part of that will be in daylight for eastern time zones.

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week it will be located less than a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or celestial east). The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster will be located the same distance to Uranus’ left. The magnitude 5.8 planet is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look, especially in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 1 at 3:30 pm EST. Since August will feature two full supermoons, we’ll focus on moon doings. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday evening, August 2 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, A Visit to the Perth Observatory, and how to forecast smoke that will affect stargazing. Details are here.

If it’s sunny on Saturday morning, August 5 from 10 am to noon, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside the main doors of the Ontario Science Centre for Solar Observing. Come and see the Sun in detail through special equipment designed to view it safely. This is a free event (details here), but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!