Evening Mars near Uranus, Suppertime Mercury Swings Sunward, and the Full Wolf Moon Meets the Winter Hexagon!

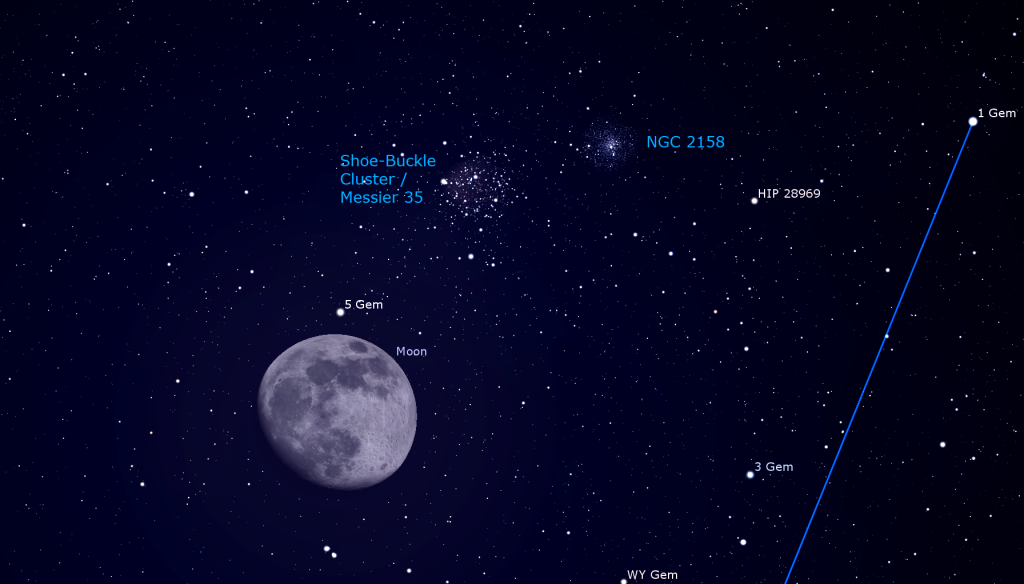

This image of Messier 35, also nick-named the Shoe-Buckle Cluster, was captured by Fred Espenak on March 29, 2011 from his home in Arizona. He affixed his Canon EOS 550D camera to a Takahashi 180mm Astrograph telescope. The photo spans about a thumb’s width top to bottom. Messier 35 is about 2800 light-years away from us. The smaller, dense group of stars to the lower right is the even more distant cluster NGC 2158. Fred’s gallery of astro-images are posted at http://www.astropixels.com/main/photoindex.html

Hello, late January stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 24th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

A bright moon will shine in the evening sky all over the world this week. It will sit close to the Shoe-Buckle Star Cluster on Monday night, and then reach its full phase on Thursday afternoon – all while passing through the huge Winter Hexagon asterism, so let’s talk about the stars that form that shape. The planets are beginning to gather in the eastern pre-dawn sky where we can’t easily see them. In the meantime, the red planet Mars still shines during evening – not too far from blue-green Uranus – and Mercury will be visible in the southwest after sunset. Read on for your Skylights!

Sirius and the Winter Football!

If you’ve been out under clear skies lately, you can’t have missed the sprinkling of incredibly bright and colourful stars in the eastern evening sky. Some of the brightest stars form a huge six-sided star pattern (or asterism) called the Winter Hexagon (or Winter Football, for NFL fans).

By 8 pm local time, all of the stars that we’ll need to make the asterism are visible. The very bright, white star hugging the southeastern horizon is Sirius, nicknamed the Dog Star, in the constellation of Canis Major (the Big Dog). After our sun, Sirius is the brightest star in all the sky. It is not only about 25 times more luminous than our sun, but is also only a mere 8.6 light-years away! On top of that, it is actually heading towards us, and will brighten over the next millennia!

Sirius is famous for exhibiting flashes of intense colour as it twinkles. This is due to combining its brightness with the extra blanket of air it must shine though when it is low in the sky. The ancient Egyptians linked their calendar to the arrival of Sirius in the pre-dawn sky because it signaled the onset of the Nile floods around the beginning of summer. In China, Sirius is called Tiān Láng天狼, aka “the Celestial Wolf”. Many First Nations cultures saw a dog’s shape in Canis Major’s stars and called Sirius the Moon Dog Star (Inuit), the Wolf Star (Pawnee), and the Coyote Star.

Moving counter-clockwise, look above and to the right of Sirius for the bright, bluish star Rigel, which marks the foot of Orion (the Hunter). The constellation of Canis Major is very obviously a dog shape – with the head upwards, tail to the lower left, and feet to the west (right). Can you see the dim stars of the constellation Lepus (the Rabbit) below Rigel? The big dog is chasing it!

Almost three fist diameters above (or 26° to the celestial north of) Rigel is the orange star Aldebaran in the constellation of Taurus (the Bull). Aldebaran is an old, red-giant star more that forty times the diameter of our sun.

Three fist diameters to the upper left (or 31° north) of Aldebaran sits the bright yellow star Capella, the Goat Star, in the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer). The form of Auriga is a crooked ring of medium bright stars with Capella at the top as the “diamond”. Moving three fist diameters down and to the left (or 32° southeast) of Capella we encounter a pair of bright stars – the twins Castor (higher) and Pollux (lower) in the zodiac constellation of Gemini. Castor is a pretty double star in a small telescope. The bodies of the twins extend sideways towards Orion.

On our way to completing the circle, look about midway between the twins in Gemini and Sirius for the bright blue-white star Procyon in Canis Minor (the Little Dog). At only 11 light-years away, it’s practically in our neighbourhood, too! Unlike his big brother, the constellation Canis Minor has only two significant stars – Procyon, and a dim, but visible star named Gomeisa that sits four finger widths to the upper right of Procyon.

The surface temperature of stars varies depending on their size, composition, and age, and this affects what colour we see them as. Our sun is a yellow star burning at about 5,500 degrees Celsius. Orange and red stars’ surfaces are cooler, with Aldebaran estimated to be at 3,600 degrees. White and blue stars are hotter. Sirius’ temperature is estimated to be nearly 10,000 degrees! One thing they all have in common – the cores inside the stars are at temperatures of millions of degrees! This is where the nuclear fusion that makes them shine is happening.

We can turn our football into a capital letter “G” by connecting Rigel to the bright, reddish star Betelgeuse (many pronounce it as “beetle juice”), which marks the eastern shoulder of Orion. This star is a true giant – believed to be more than 600 times the size of the sun! It’s also nearing the end of its days – when it will explode as a tremendous supernova; but we’re in no danger when it does. Notice that Betelgeuse is not quite as strongly coloured as Aldebaran.

The Winter Hexagon is visible on the same dates and times every year, and will remain in view until about mid-April. The Winter Milky Way rises up through it – and the moon and planets wander through those stars as they travel along the Ecliptic. The nearly full moon entered the hexagon last night (Saturday), and will take three nights to cross it.

The Moon

The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. At some point, early people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve or thirteen full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night; lighting the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and workers in the fields devoting extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The Indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call the January full moon Gichi-manidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirit Moon”. (You might recall that name from hearing or singing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.) For the Ojibwe people January is a time to honour the silence, and recognize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures.

The Algonquin of the Great Lakes call it Squochee Kesos, “the sun has not strength to thaw” moon. The Haida’s of western Canada and Alaska use Táan Kungáay, the Bear Hunting Moon. The Cree of North America call the January full moon Opawahcikanasis, the “Frost Exploding Moon”, when trees crackle from the extreme cold temperatures. For Europeans, the January full moon is commonly known as the Wolf Moon, Old Moon, or Moon after Yule. The Wolf Moon name might be derived from North American First Nations traditions, although some think it has an Anglo-Saxon origin. In either case, it’s likely that the hungry wolves calling to one another in the dead of winter would leave an impression on anyone before our modern era.

On Thursday afternoon, January 28 at 2:16 pm EST (19:16 UT or Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will reach its full moon phase. While already starting to wane, the moon will still look full when it rises several hours later. Full moons in January always shine in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins) or Cancer (the Crab). Since they are, by definition, opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, full moons are always fully illuminated – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes climb as high in the sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

This will be another terrific week for viewing the moon worldwide. Early in the week, our planet’s partner will already be shining in the eastern sky before sunset, allowing even the youngest stargazers to see its sights before bedtime! And next weekend, it will be rising at sunset and shining all night long. Don’t forget that you can safely view the moon in your telescope in daytime, too – as long as you take care not to let anyone aim the telescope near the sun. Parental supervision is a must.

Today (Sunday) the moon will rise after lunch in its waxing gibbous (i.e., more than half-illuminated) phase, and set at 10 pm local time. Once the sky darkens, you’ll see that the moon is tucked between the horns of sideways Taurus (the Bull).

Once the sky darkens on Monday, skywatchers can look for the large open star cluster known as Messier 35, or the Shoe-Buckle Cluster, sitting just to the upper right (celestial west) of the moon in Gemini (the Twins). During the night the moon’s orbital motion will draw the moon farther from the cluster, and the diurnal rotation of the sky will lift the moon higher compared to the cluster. To best see Messier 35’s stars, hide the bright moon just beyond the left edge of your binoculars’ field of view.

After crossing the Winter Hexagon and passing its full phase, the moon will spend Wednesday and Thursday in Cancer (the Crab), but that constellation’s stars aren’t bright enough to see next to the bright moon using unaided eyes.

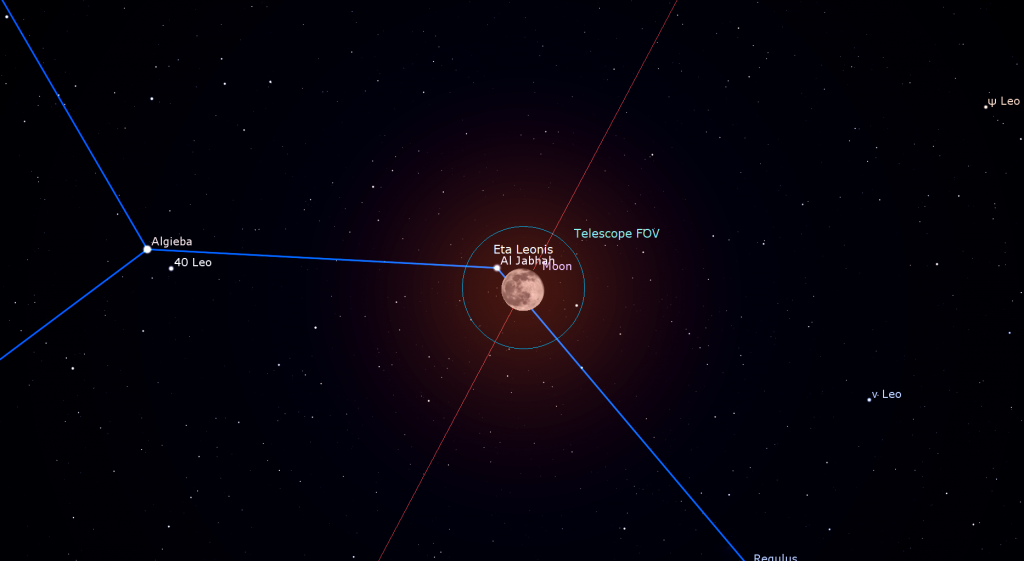

On Friday night, the still very bright moon will pass very close to the bright, magnitude 3.45 star Eta Leonis (η Leo and Al Jabhah), which marks the lion’s chest. Observers across the southern half of the continental USA, Mexico, Central America, and northern South America can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) the star. In the GTA, we will see the moon closest to the star at about 10:50 pm EST. To see the moon orbiting Earth in real time, glance at the moon and the star every now and again on Friday night and note how their positions change. (While the entire sky is being carried east to west, it’s the moon that’s sliding eastward continuously compared to the fixed star.)

The waning moon will end the week in Virgo (the Maiden), and sitting about a fist’s diameter to the lower right of the bright star Denebola, which marks the tail of the lion.

The Planets

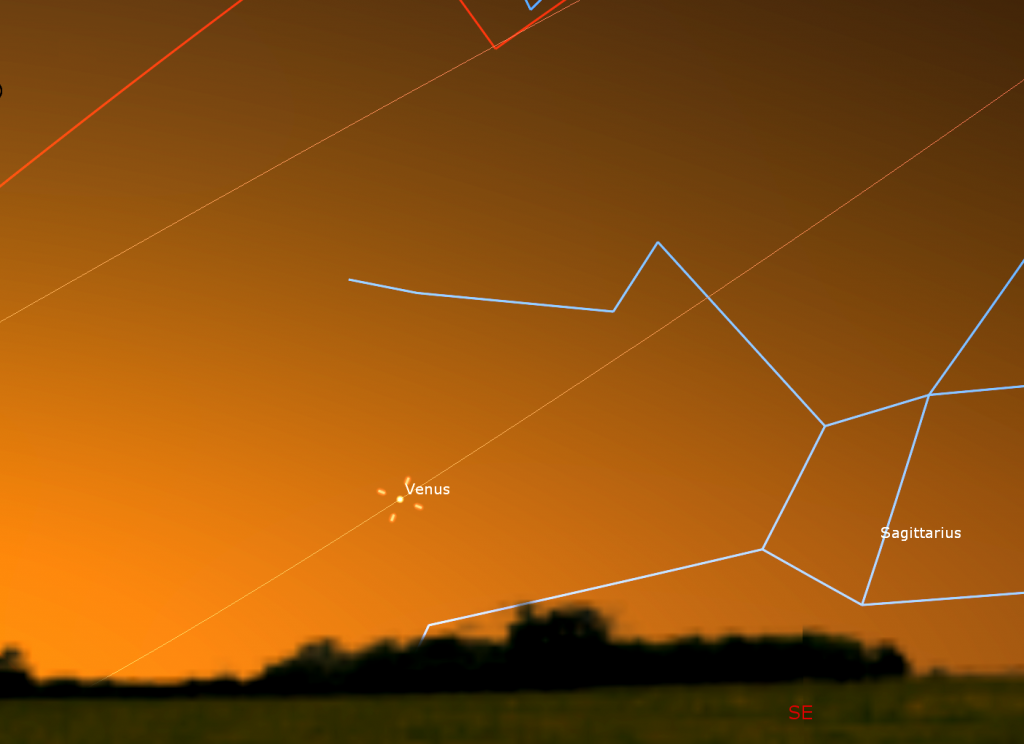

We’re about to enter a planet-viewing drought because nearly all the planets will be gathering in the eastern predawn sky – and too close to the sun to easily see them. Venus will return to view in the western sky after sunset from late April onwards – but Jupiter and Saturn won’t return to the evening sky until June.

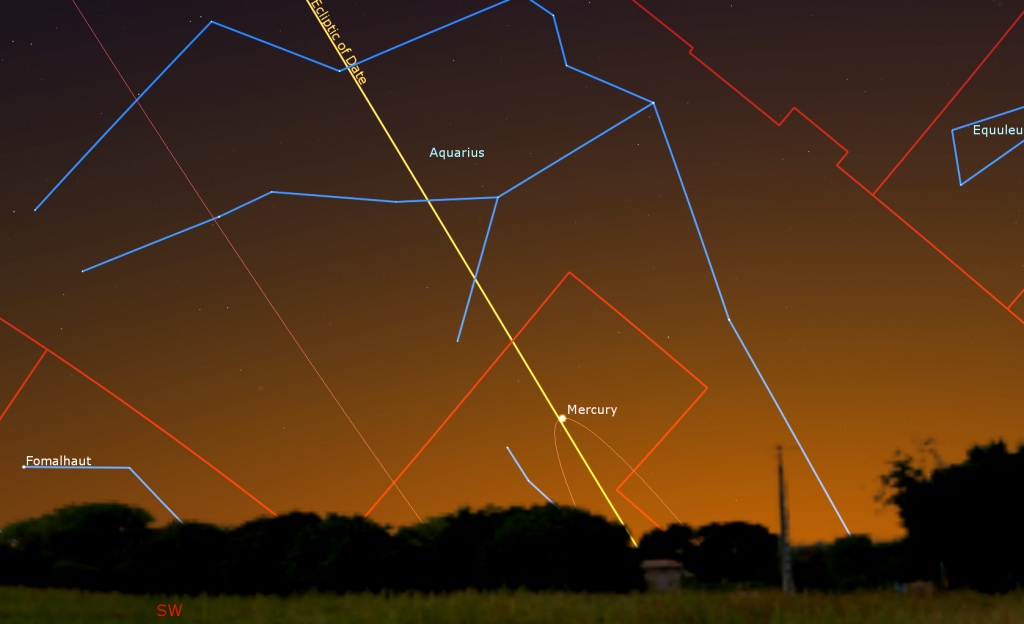

After reaching its maximum visibility yesterday (January 23) for the current evening appearance, Mercury will still be fairly easy to see after sunset this week – but you’ll need an unobstructed view of the southwestern horizon, and no clouds. Tonight (Sunday) you can start looking for the speedy planet at about 5:40 pm in your local time zone, when it will sit about a fist’s diameter above the horizon. The best viewing time, with the sky darkening, but the planet brightening while it descends, will be the minutes up to 6 pm local time. You can continue to look for Mercury every night this week, but the sky around it will be brightening as the sunsets arrive later. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. Be sure that the sun has completely disappeared below the horizon before you search for Mercury with binoculars and telescopes.

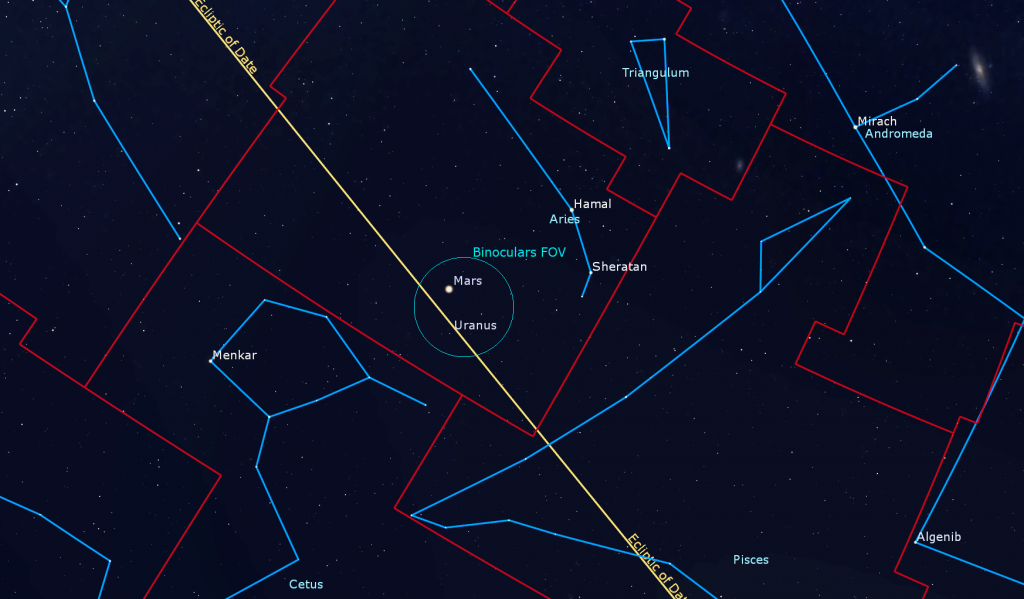

Mars is still available for evening viewing after dusk every night, but it is far fainter, and smaller in telescopes, than it was last fall. Mars will be highest in the southern sky at dusk and then it will descend all evening and set at about 1 am local time. Look for the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) to the upper right (8.5 degrees to the celestial north) of Mars. Hamal is brighter, at magnitude 2.0, and Sheratan is a bit fainter at magnitude 2.6.

Mars recently sped past dim Uranus, and continues to leave it in its red dust! Tonight (Sunday), the fainter, distant planet will sit about two finger widths below Mars. By next Sunday, that will increase to nearly a palm’s width (6°). View Uranus earlier in the evening when it’s higher in the sky and seen through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. In a telescope, Uranus will resemble the stars near it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much as they do, and it will show a blue-green colour.

This week, you might be able to glimpse bright Venus sitting low over a low and cloudless southeastern horizon after the planet rises at about 7 am. The sun rises about 20 minutes later. Venus has been sliding towards the sun for some time now, and only its intense magnitude -3.9 brightness has kept it visible within the dawn glow.

The Bright Stars of January

If you missed last week’s guide to the many bright stars you can pick out with your unaided eyes in the evening sky over the next month or so – even when the moon is around – I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday afternoon, February 2 at 3:30 pm EST. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

On Sunday afternoon, February 8 from 1 to 2 pm I’m hosting an online session for RASC called Ask an Astronomer in support of the David Dunlap Observatory! We’ll explore the night sky together and answer your astronomy and space-related questions in simple language – using pictures, illustrations and planetarium software. The deadline to register is Friday February 26 at 3:00pm. Registration is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!