Good Views of the Full Moon after Yule, Double Stars Don’t Mind Moonlight, and Planets Will Dance at Dawn and Dusk!

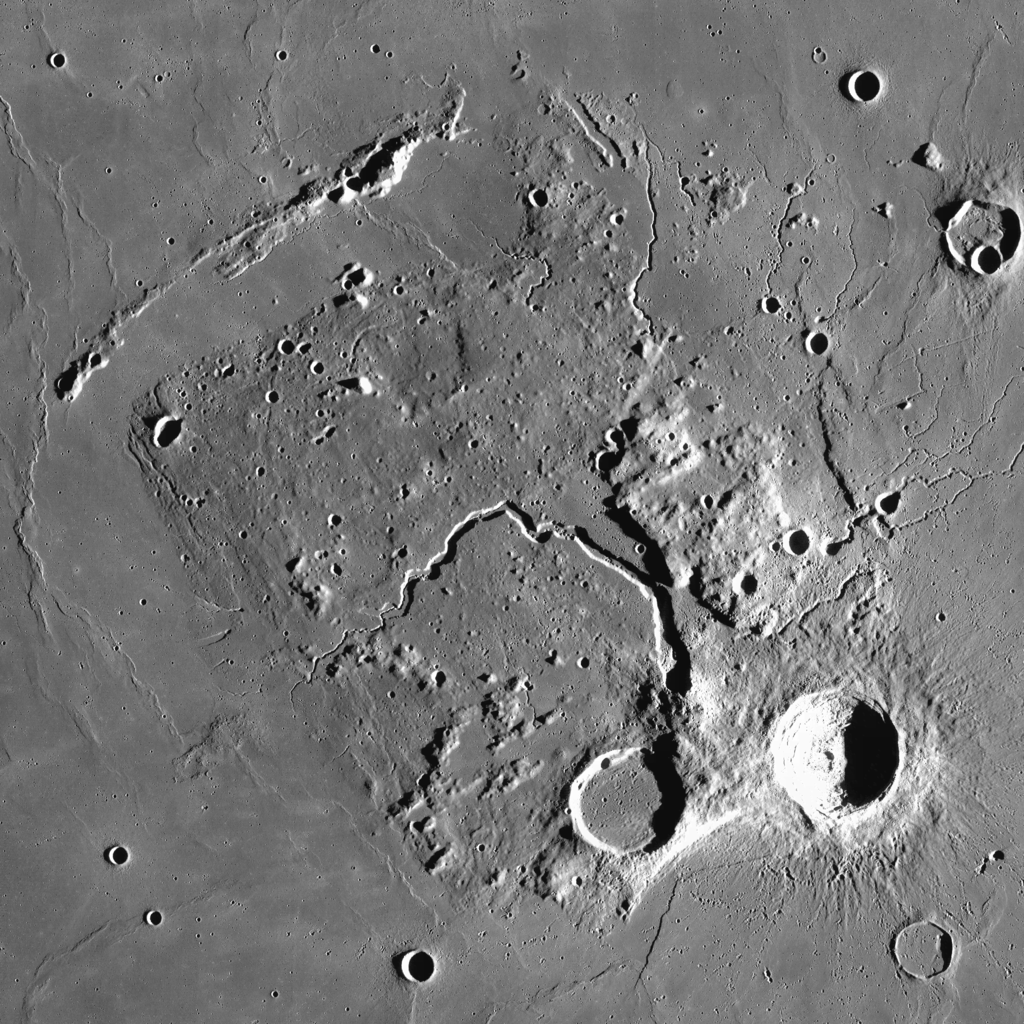

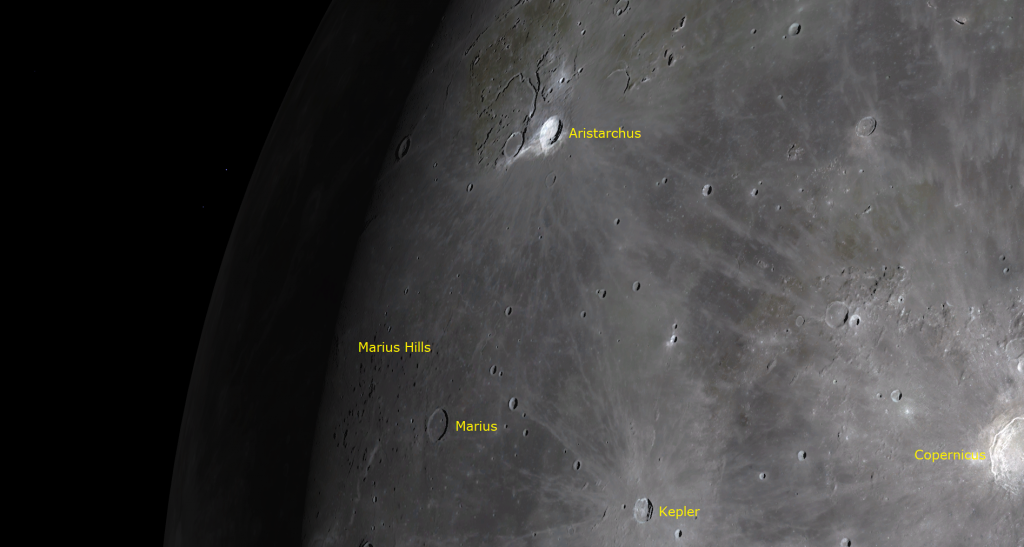

This image taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the fascinating Aristarchus Plateau. The crater Aristarchus at lower right is very prominent, and can be seen even with unaided eyes as a very bright patch. To its left is the similar-sized, but darker crater Herodotus. Vallis Schröteri, the largest sinuous rille on the moon, starts at a broad section near Herodotus, called the Cobra’s Head, and winds to the north, tapering along the way. All of those features sit within the elevated, rough-surfaced, diamond-shaped plateau.

Hello, January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 21st, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will continue to shine brightly in evening worldwide this week as it waxes through the full Moon after Yule, so I highlight some sights to see on it and share some bright and easy to see double stars that don’t mind moonlight. We’ll soon lose Saturn and Neptune from evening, but Jupiter and Uranus will remain. Swinging-sunward Venus will watch Mercury kiss Mars in the morning east. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will dominate the evening sky worldwide this week. Its intense light will wash out the winter Milky Way and all but the brightest stars, but we can still enjoy its own fascinating geography, or selenography, to be precise. We can also turn our binoculars and backyard telescopes on double stars and bright star clusters. I’ll share more on them below.

Today (Sunday) the 87%-illuminated waxing gibbous moon will rise after lunch hour. You can safely view the pale daytime moon under magnification as long as you avoid aiming any optics sunward (parental guidance is a must for junior astronomers). The polarized filters found in most sunglasses and cinema 3D glasses will darken the sky and increase the contrast on the moon when turned at certain angles.

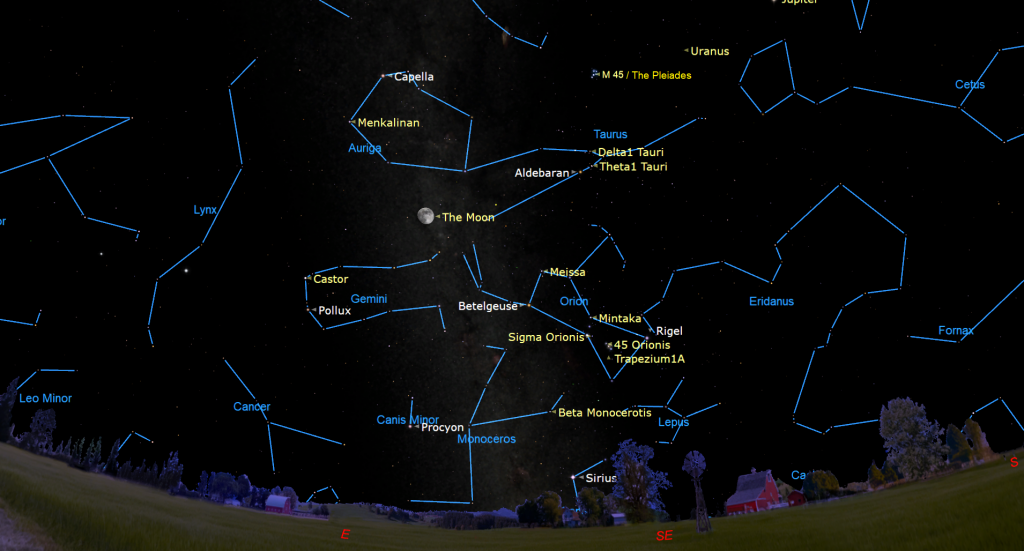

As the sky darkens the brightest stars of the Winter Hexagon will appear around the moon. Also known as the Winter Football and Winter Circle, the giant asterism is composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major (the Big Dog), Orion (the Hunter), Taurus (the Bull), Auriga (the Charioteer), Gemini (the Twins), and Canis Minor (the Little Dog) – specifically the stars Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon, in counter-clockwise order. The ecliptic crosses the upper (northern) third of the shape, so the moon makes a trip through it every month.

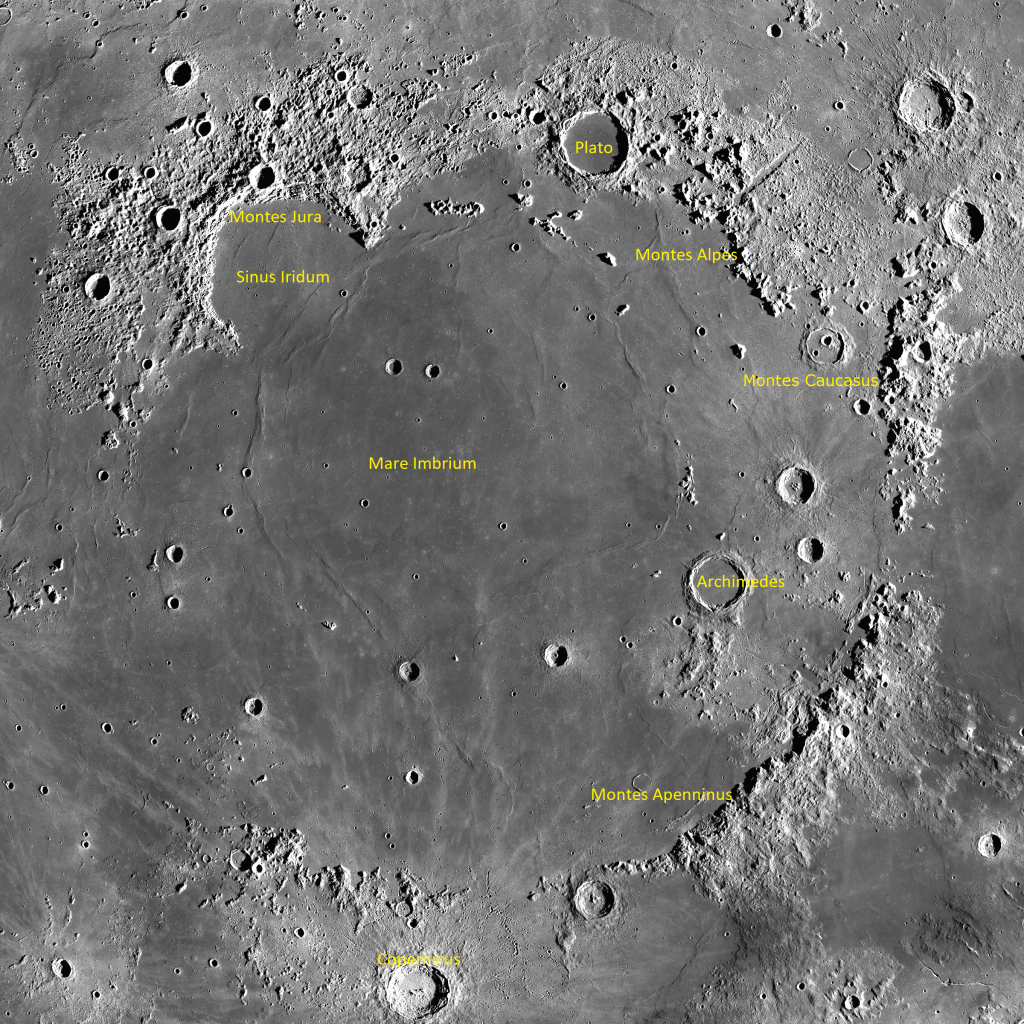

Sunday’s moon will sit just inside the western edge of the football, between orange Aldebaran and yellowish Capella. The curved terminator boundary separating the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres will fall close to the left-hand (lunar western) edge of Mare Imbrium “the Sea of Rains/Showers/Tears”. That huge, circular impact basin dominates the moon’s northwestern quadrant. Uranium-lead isotopic dating methods applied to samples of Imbrium rock returned by Apollo 15 astronauts, who visited the basin’s edge, and other robotic missions, yield estimates of 3.922 billion years for the age of the original impact – placing it in the late heavy bombardment era of 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago. Material ejected during the Imbrium impact has been spread widely across the moon’s surface. The lavas that filled the basin 500 million years later has produced a darker, smoother, less-cratered surface.

Mare Imbrium is 1,145 km wide and very circular in form, making it the largest and youngest of the impact basins on the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. To the unaided eye, its eastern side (on the right when viewing the moon from the Northern Hemisphere of Earth) touches smaller Mare Serenitatis. Three impressive, curved mountain chains surround the eastern rim of Mare Imbrium – extending north and south of the two maria’s contact point. The mountains are actually segments of the original basin’s rim. But at this late phase of the lunar month, when the sunlight is illuminating them from above, the mountains won’t look as spectacular.

What will be impressive under magnification is Sinus Iridum “the Bay of Rainbows”. The circular, 249 km-wide feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded “handle” on the western edge of that mare.

The rising sun along the terminator will brighten the prominent curving Montes Jura mountain range that surrounds Sinus Iridum on the north and west. Look for the lunar promontories named Heraclides and Laplace that poke into Mare Imbrium to the south and north of the bay, respectively. Your telescope will show you that Sinus Iridum is almost craterless – so we know that it is geologically young. But it does host a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are nicely revealed at this lunar phase.

From Monday to Thursday, the moon will wax in phase and rise almost an hour later each day while it journeys across the stars of Gemini (the Twins) and then Cancer (the Crab). On those nights, use your binoculars or telescope to look at the very bright spot of crater Aristarchus gleaming within a sea of dark grey rock near the moon’s lower left-hand (western) rim. It occupies the southeastern corner of a diamond-shaped plateau that is one of the most colorful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Use a telescope and high magnification to view features like the large, sinuous rille named Vallis Schröteri. Its snake-like form begins between Aristarchus and next-door crater Herodotus and slithers across the plateau. I never tire of looking at it!

The large craters Copernicus and Kepler to Aristarchus’ lower right are surrounded by large, ragged ray systems – ejecta and secondary impacts from their formation. The straight arcs of Tycho’s rays, which sits in the moon’s lower (southern) region, will be seen to spread far across the moon. When the moon is opposite the sun in the sky, there are no shadows cast anywhere. All the variations in tone are produced by the various rock types on the surface – darker where the late-arriving basalt is and brighter where the old, original, crystalline, aluminum-rich anorthosite is. The ray systems are everywhere!

The moon has always shone down upon the people of Earth. At some point, we began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons in order to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrations. Full moons naturally became celestial time keepers since they were obvious to everyone and conveniently rose at sunset. Moreover, the full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night. It lit the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and let workers in the fields devote extra hours to get the harvest in.

On Thursday, January 25 at 12:54 pm EST 9:54 am PST, or 17:54 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will reach its full moon phase. Full moons in January always shine in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins) or Cancer (the Crab). Since they are, by definition, opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, full moons are always fully illuminated – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes climb as high in the sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows. This full moon will reach a less lofty height than December’s did, but its excursion of 4.5° north of the ecliptic (due to the moon’s orbital inclination) will add some elevation when it culminates due south around 1 am local time.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The Indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call the January full moon Gichi-manidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirit Moon”. (You might recall that name from hearing or singing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.) For the Ojibwe, January is a time to honour the silence, and recognize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures.

The Algonquin of the Great Lakes call it Squochee Kesos, “the sun has not strength to thaw” moon. The Haida’s of western Canada and Alaska use Táan Kungáay, the Bear Hunting Moon. The Cree of North America call the January full moon Opawahcikanasis, the “Frost Exploding Moon”, when trees crackle from the extreme cold temperatures. For Europeans, the January full moon is commonly known as the Wolf Moon, Old Moon, or Moon after Yule. The Wolf Moon name might be derived from North American First Nations traditions, although some think it has an Anglo-Saxon origin. In either case, it’s likely that the hungry wolves calling to one another in the dead of winter would leave an impression on anyone before our modern era.

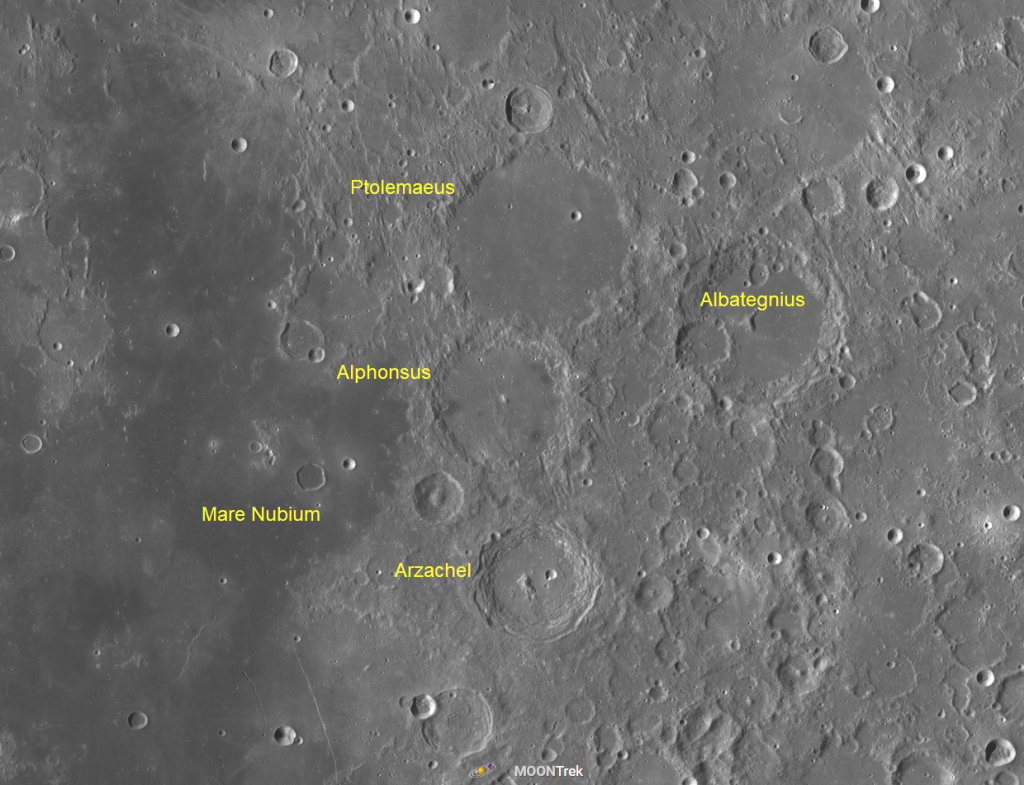

While the moon is quite full, you can use your telescope to look at the dark stains left behind by extinct volcanoes on the moon! Alphonsus is a 110 km wide crater located just south of the moon’s centre, on the upper right shore of Mare Nubium. Any size of telescope will reveal a triangle formed by dark spots on the crater’s floor near its left and right rims. Those are ash deposits. Atlas, another crater with similar markings, sits in the northern region of the moon, about halfway between the northern shore of Mare Serenitatis and the edge of the moon.

The waning gibbous moon will spend the rest of this week passing through the constellation of Leo (the Lion). On next Sunday night, it will still be rather bright when it rises around 8:30 pm local time. But darker skies will soon arrive!

The Planets

The sun is setting noticeably later now at the latitude of Toronto – about 1.5 minutes later per day! That delayed onset of darkness is taking away our good telescope viewing-time for Saturn. Tonight (Sunday) the ringed planet’s dot will appear above the southwestern horizon as the sky darkens. By the time you can spot it in your binoculars or telescope, it will be sinking below 20° elevation – about the cutoff for crisp views of things in the sky. Your mileage may vary, depending on the turbulence of the air to the west of you. Saturn will set around 8 pm local time.

Powerful binoculars can hint that Saturn has rings, but any size, style, or brand of telescope will let you see them. A better quality of telescope will show them more clearly. Saturn’s brighter moons array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet – though only Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan might be visible from here on out.

During this week, Titan’s counter-clockwise migration around Saturn will carry it from close-in at the lower left of Saturn (or celestial southeast) tonight, to much farther to Saturn’s lower right at mid-week, and then back to Saturn’s lower right (or celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.)

The faint, blue, ice giant planet Neptune is 20° east of Saturn on the ecliptic, putting it almost two hours behind Saturn and granting us an extra week or so to catch sight of it in telescopes. Decent views of Neptune will end around 7:30 pm local time, then it will set around 9:30 pm. The magnitude 7.9 outer planet will be harder to find this week due to the bright moon.

Thankfully, we still have many hours to enjoy Jupiter every night. Its extremely bright, white dot will catch your eye in the south-southeastern sky at dusk and peak telescope-time will arrive around 6:30 pm, when it will be highest due south. The planet will set in the west around 1:30 am. Any decent pair of binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another.

In the Americas on Sunday night, Io will disappear in binoculars when it crosses Jupiter’s disk from 6:45 to 9 pm EST. Telescope owners can watch its round black shadow follow it from 8:10 to 10:17 pm EST (or 01:10 to 03:17 GMT on Monday). Io will pop into view as it emerges from behind the left-hand (eastern) side of Jupiter on Monday at 7:16 pm EST (which converts to 00:16 GMT on Tuesday). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.) The moons will pair up on each side of Jupiter on both Saturday and next Sunday evening.

Any small, decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time tonight (Sunday), Friday, and next Sunday. It’ll appear late on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday night. The spot has been rather pale pink for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

On Friday, Jupiter will arrive at a 90° angle from the sun – or east quadrature as astronomers call it. On the nights surrounding quadrature Jupiter will be reduced in illuminated phase to only 99%. In a telescope that will give Jupiter a dimmed, less distinct eastern limb and a sharper, brighter western limb, i.e., the sun-facing side.

Uranus is following Jupiter across the sky every night and setting by 2:30 am local time. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes under moonless conditions, but the bright moon will interfere with that this week. The blue-green planet’s speck will be positioned 1.2 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper left (or 12° to its celestial ENE). When the moon isn’t around the bright Pleiades star cluster sparkling a generous fist’s width to Uranus’ upper left (or 11.8° to its celestial northeast) can guide you to the planet. On Saturday, the motion of Uranus through the background stars of southern Aries (the Ram) will slow to a stop – completing a westward retrograde loop that it began in late August. In the weeks to come, the planet will begin to creep eastward again.

Venus, Mercury, and Mars are available to view in the eastern sky before sunrise this week – but all three are on the move, both due to our orbital motion and their own.

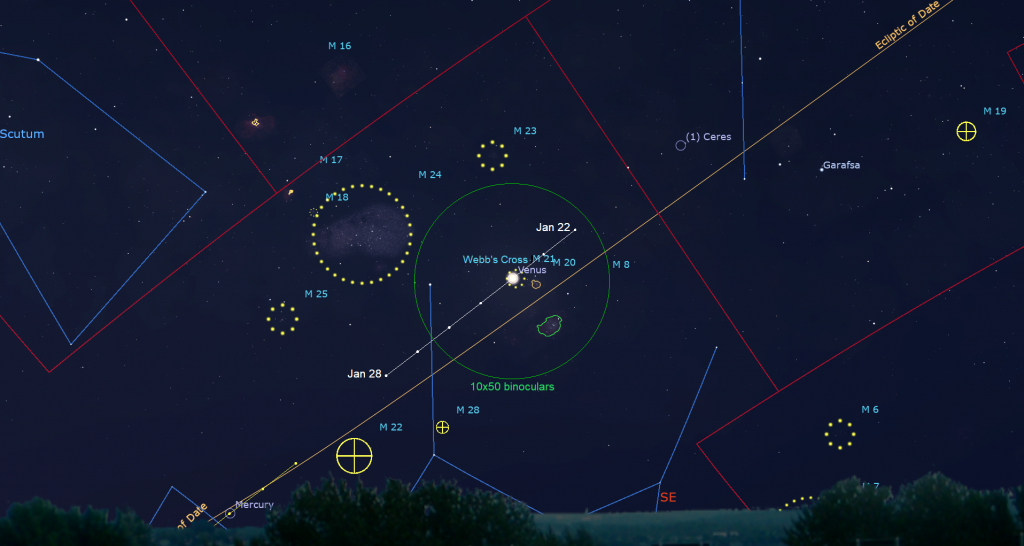

After many months as the brilliant “Morning Star”, Venus is rapidly swinging toward the sun, shortening the time that it is visible every morning. This week Venus will travel eastward by more than an outstretched palm’s width – but by the time the planet has cleared the rooftops around 6:30 am local time, the stars of northern Sagittarius (the Archer) it is passing through will be hidden by the dawn twilight. Venus will remain as a gleaming point of light until sunrise. By the way, if you see a gleaming dot drifting left or right, it’s an aircraft, not Venus.

Viewed through a telescope this week, our next-door planet will show a shrinking, overinflated football shape spanning 12.6 arc-seconds. On Wednesday morning, January 24 Venus will pose at the edge of the bright open star cluster known as Messier 21 or Webb’s Cross. If you head outside by about 6:30 am local time that morning, binoculars may show its tight knot of stars sprinkled just to Venus’ lower right. The cluster will be positioned to Venus’ lower left and upper right on Tuesday and Thursday morning, respectively. Venus will be parked near more of the Messier objects next Sunday, but they will be too low in the sky to see them clearly unless you are located near the tropics. I’ll post Venus’ path here.

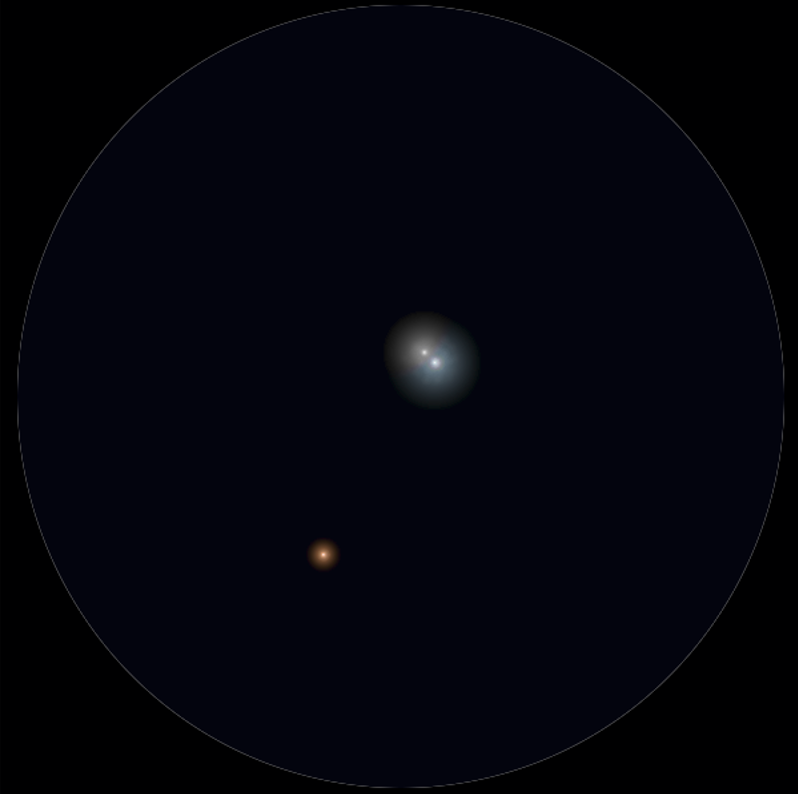

Observers near the tropics will more easily see Mercury and Mars – but those of us at middle latitudes with unobstructed haze-free skies can try, too. Like Venus, Mercury is travelling down towards the sun every morning, albeit more rapidly. Meanwhile, Earth’s orbital motion is allowing Mars to climb away from the sun. After Venus kisses Mars on February 22 in one the year’s best conjunctions, Mars will stand alone before sunrise, except for a brief re-appearance of Mercury in early May.

Speaking of conjunctions… on the mornings surrounding Saturday, January 27, Mercury will pass very close to Mars. Look for their conjunction just above the southeastern horizon after they rise shortly after 6:30 am local time. The two planets will be close enough to share the view in a backyard telescope from Thursday to next Monday and through binoculars for many mornings prior and beyond that. Before Saturday, Mars will be positioned to Mercury’s lower left. At their closest approach on Saturday, Mars will be positioned just 0.25 degrees below four times brighter Mercury. Then Mars will switch to Mercury’s upper right. Telescope views of objects that low in the sky will be impaired by the increased blanket of intervening air. Remember that your optics may flip and/or invert the scene, and be sure to turn all optics away from the horizon before the sun rises.

Seeing Double in January

A bright moon does not prevent us from viewing stars in binoculars or a telescope – as long as we can find them. To double (or triple) our pleasure we can focus on double stars, the term used to describe two or more stars that are either orbiting close to one another in a binary star system, or those which appear to sit near one another but are actually at vastly different distances from us. We call those line of sight double stars. The stars can look the same, like distant car headlights, or they can shine with different brightnesses and contrasting colours.

A great many of the stars you see in the sky have close-in partners. Thank fully for beginners, some of January’s brightest lights are double. Here are a few terrific double stars to check out in January, moonlit or not.

Alnitak and Mintaka, the stars at either end of Orion’s Belt, have smaller partners that appear under magnification. The medium-bright star that sits a finger’s width to the lower right of Alnitak is actually a spectacular group of stars named Sigma Orionis that will show nicely in binoculars – as will Meissa, the star that marks Orion’s head. It’s a gorgeous group under any magnification. The stars in Orion’s Sword are pleasingly grouped. If you focus your attention at the fuzzy Orion Nebula in the sword’s centre, you may be able to tease apart the four brightest stars clumped together in its core. Those are the Trapezium Cluster or the Theta Orionis complex.

Many of the stars in the triangular grouping that forms the face of Taurus (the Bull) are well-separated double stars ideal for binoculars. While you are in the neighbourhood, spend some time viewing the Pleiades cluster above it.

Very bright Castor, the higher of Gemini’s twin stars, is a triple delight in telescopes. Looking upwards, the star that sits a palm’s width below bright, yellow Capella is Menkalinan. It has a bright little red companion to its left named Pi Aurigae.

The Bright Stars of January

If you missed last week’s guide to winter’s stars seem to be the brightest stars I posted it with sky charts showing where each of these stars are here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!