Matariki for the Maori and the Morning Moon Joins Jupiter in Daytime, Letting Us See Sights in Mighty Hercules!

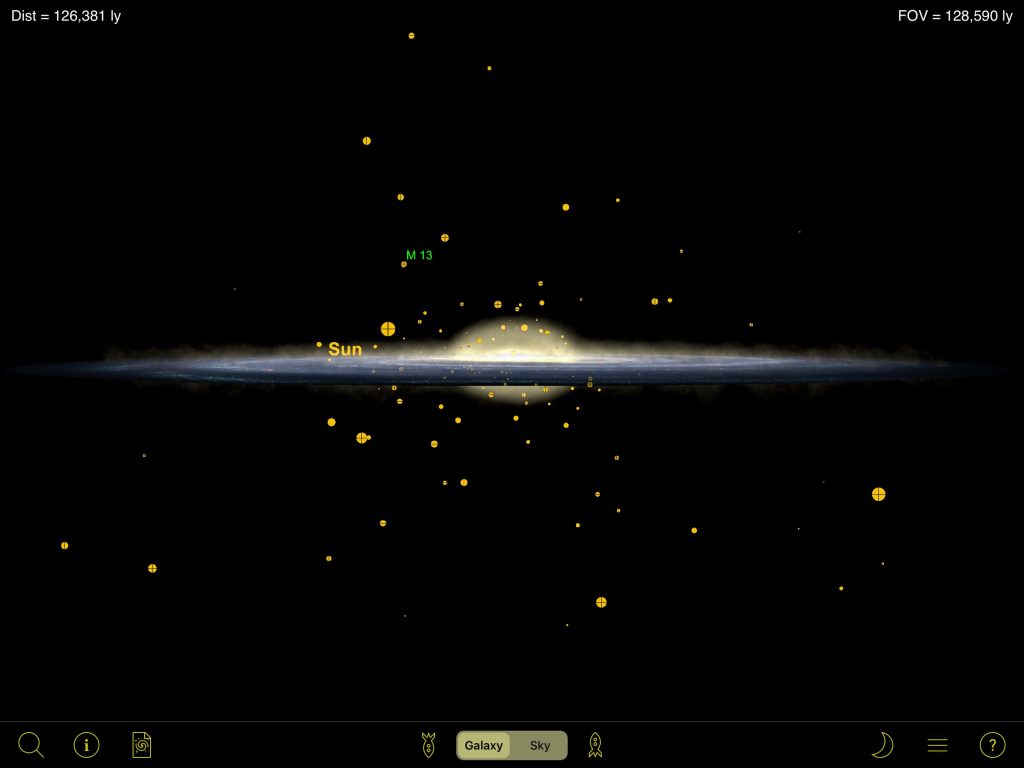

This image of Messier 13, the Great Globular Star Cluster in Hercules was imaged by Claudio Oriani in Richmond Hill, Ontario on May 30, 2023 using an 8″ SCT telescope. The cluster, also known as NGC 6205, is 24,000 light-years away from our sun. The cluster appears as a faint fuzzy patch in binoculars, and sugar spilled in black velvet in a good backyard telescope under dark skies. See more of Claudio’s work at his site https://www.wondersofthesky.com/

Hello, Dark Sky Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 9th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waning moon will spend this week in the pre-dawn and morning daytime sky, where it will guide you to Jupiter in daylight, then pose near Uranus and the Pleiades. Speaking of that famous star cluster, this week marks Matariki, or Maori New Year. In evening, Venus drops lower while Mars attacks Regulus, and I tour you through the sights of Hercules. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

At long last, this week will deliver the first of two moonless periods of fully dark, summer night skies for Northern Hemisphere observers living south of about 55° N. (Unfortunately, the skywatchers north of that latitude – in Scandinavia, Russia, Alaska, and Northern Canada – will be seeing twilit skies at midnight.) Southern Hemisphere astronomers will continue to enjoy long winter nights there – but theirs will be moonless, too!

The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon tonight (Sunday, July 9) at 9:48 pm EDT or 6:48 pm PDT, in the Americas. That converts to Monday at 01:48 Greenwich Mean Time. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon is 90° ahead of the sun in the sky, causing our natural satellite to appear half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time, climb the southeastern sky during the wee hours, and then shine as a pale orb in the southern and western daytime sky until it sets in the early afternoon.

As the week unfolds, the moon will swing steadily closer to the sun, making it rise about half an hour later each night and wane in illuminated phase. That will give us even more hours to see the evening stars and the Milky Way in their full glory. And you don’t even need special equipment! (More on that below.)

When the moon rises early on Monday morning, it will be swimming with the faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes) and accompanied by the bright planets Jupiter (to the moon’s lower left) and Saturn (off to the moon’s right). The trio, plus the soon-to-rise sun, will nicely trace out the plane of our Solar System across the sky. It’ll be an especially pretty sight around 4:30 am local time.

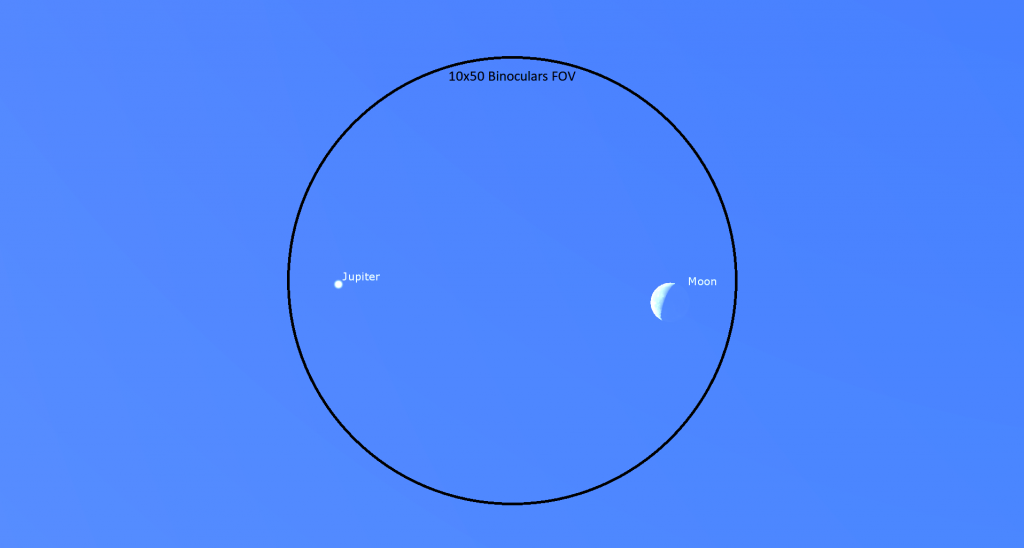

After the waning crescent moon clears the treetops in the east during the wee hours of Tuesday morning, it will be even closer to Jupiter. The pair will shine in a dark sky for two hours, below the bright stars of Aries (the Ram), and then remain visible in the brightening sky until sunrise. With each passing hour the moon will shift by its own diameter closer to Jupiter, allowing skywatchers with binoculars to glimpse Jupiter’s bright speck in daylight by placing the moon on the right edge of the field of view.

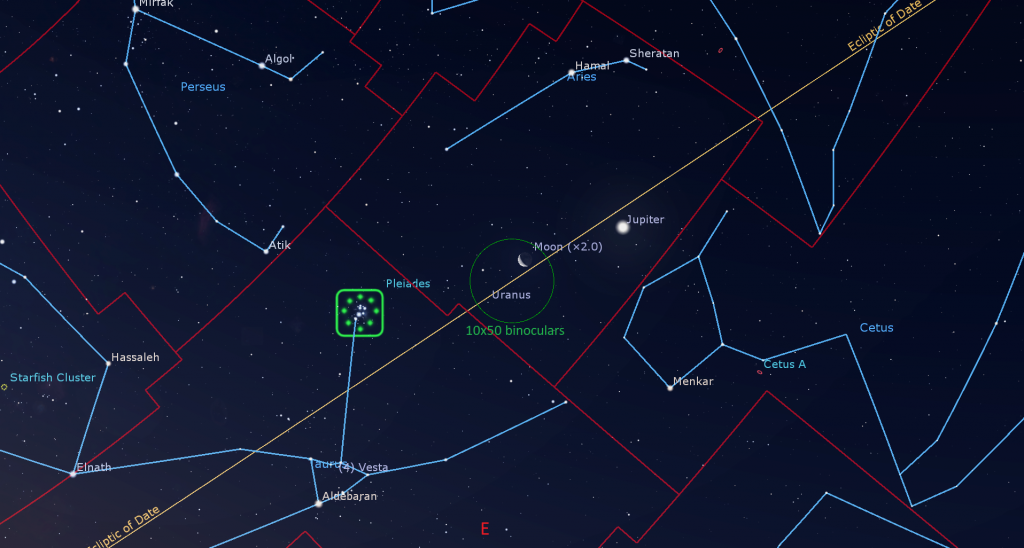

On Wednesday morning, the moon will hop east to shine a palm’s width to Jupiter’s lower left. You might still be able to find Jupiter in daytime by scanning the sky just to the right of the crescent moon. Additionally, if you head outside before the sky brightens on Wednesday, you can use the crescent moon to guide you to the tiny dot of Uranus. The magnitude 5.8, blue-green planet Uranus is visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster and bright Jupiter will shine to either side of the pairing. Before dawn in the Eastern Time zone, Uranus will be located less than palm’s width to the moon’s lower left (or 4° to its celestial east). Observers in more westerly time zones will find Uranus even closer to the moon. The medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis) will be shining two finger widths above Uranus. That star will assist your search for Uranus – even after the moon moves away on subsequent mornings.

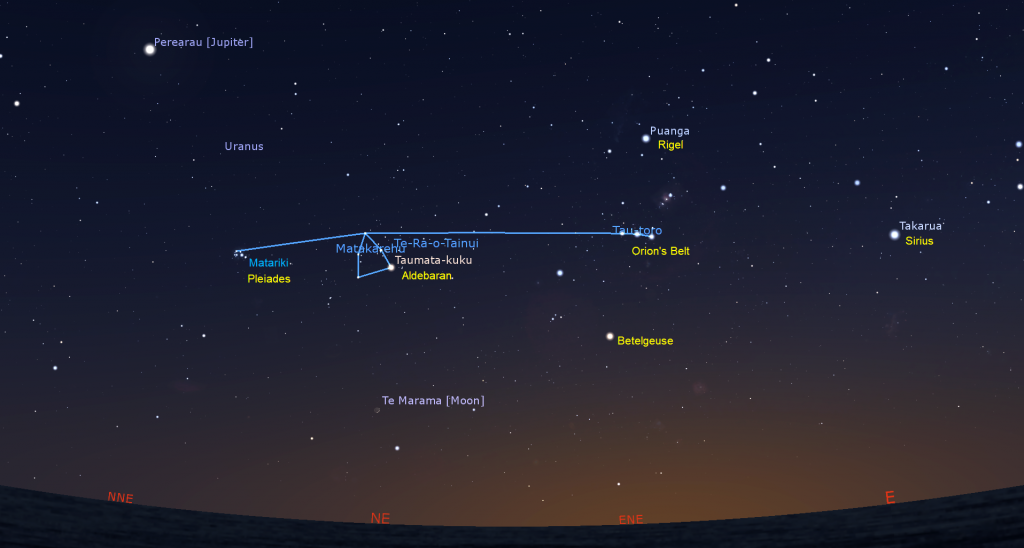

Another pretty sight will welcome early risers on Thursday morning when the slim crescent of the waning moon will shine just 2 finger widths below (or celestial south of) the Pleiades – close enough to share the view of binoculars. Look for the bright, orange-tinted star Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus (the Bull), twinkling furiously below them. The bright, yellowish star Capella in Auriga (the charioteer) will be off to their left (or celestial NNE). And, yes – those are the winter constellations lurking the pre-dawn sky!

On Friday and Saturday morning, respectively, the 5%-illuminated, old crescent moon will shine between and then below Aldebaran and Capella. For most of us, that will be our last glimpse of the morning moon, as it will spend next Sunday cozying up to the sun in Gemini (the Twins).

It’s Matariki!

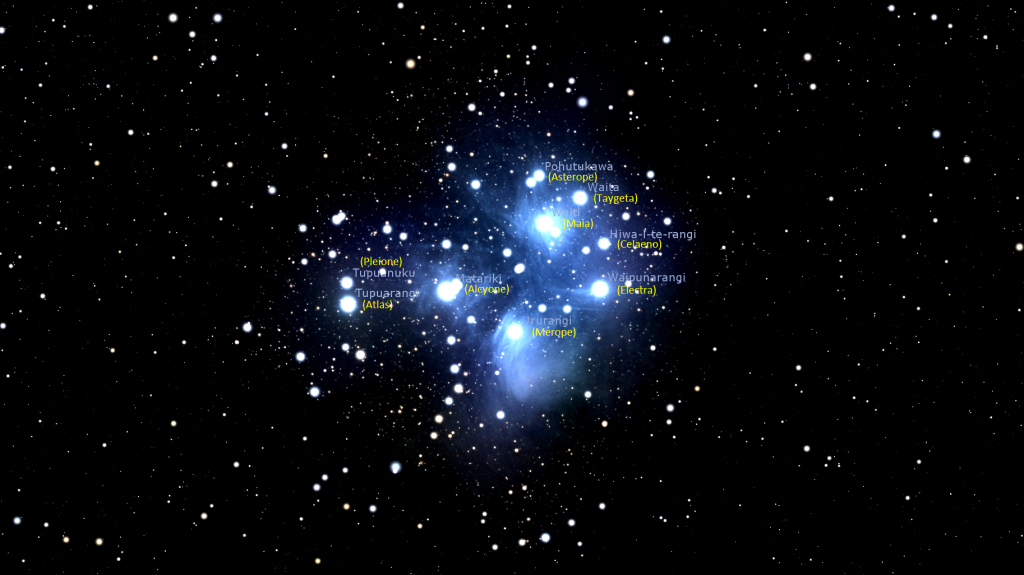

Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). At this time of year, mid-winter in the Southern Hemisphere, Taurus rises long enough before sunrise for the cluster to become visible low in the eastern sky after several months of absence from the sky for New Zealanders. Matariki’s return to sight during Pipiri (June/July) marks the beginning of the Māori new year. This year, Matariki begins on July 14. Some groups opt to use the return of the bright star Puanga, better known to us as Rigel in Orion (the Hunter), instead. In 2022, Matariki became a national holiday in New Zealand – because of astronomy!

The word Matariki is an abbreviation of Ngā Mata o te Ariki, “the Eyes of God” – referring to Tāwhirimātea, the god of the wind and weather. In the Maori story of creation, Tāne Mahuta, the god of the forest, separated his parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. His upset brother Tāwhirimātea tore out his eyes, crushed them into pieces, and threw them into the sky to become the stars.

Traditionally, Maori communities, or iwi, would gather together at night during a time of the constellation’s prominence, making use of the period between harvests to celebrate and make offerings for a bountiful future.

Traditions hold that the visual appearance of the cluster was said to predict the success of the season ahead. Clear, bright stars are a good omen, and hazy stars predict that the rest of winter during July-August will be cold and harsh. Even though one common name for the Pleiades is the Seven Sisters, nine bright stars in the cluster are visible to sharp-eyed observers. For Māori the brightness of each individual star predicts the fortunes connected to a specific thing that star represents in Māori life, such as the wind, or food that grows in trees.

There is an excellent source on Matariki at https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/discover-collections/read-watch-play/matariki-maori-new-year. I’ll post a labeled sky chart of the stars, as seen from New Zealand here.

| Māori Star Name and Aspect | Common Name | Designation |

| Matariki (the mother star, wellbeing) | Alcyone | Eta Tauri |

| Pōhutukawa (lost loved ones) | Sterope | 21 Tauri |

| Waitī (freshwater, wetlands) | Maia | 20 Tauri |

| Waitā (ocean, fish) | Taygeta | 19 Tauri |

| Waipuna-ā-rangi (rain) | Electra | 17 Tauri |

| Tupuānuku (soil crops) | Pleione | 28 Tauri |

| Tupuārangi (tree crops, birds) | Atlas | 27 Tauri |

| Ururangi (winds) | Merope | 23 Tauri |

| Hiwa-i-te-rangi (the future) | Caleano | 16 Tauri |

| (Source: New Zealand Aotearoa Ministry for the Environment) |

The Planets

If the planet Venus weren’t so brilliant (it peaked at magnitude -4.69 on Friday), we’d have lost sight of it by now. Our sister planet will first pop into view in the lower part of the western sky around sunset. That will be the best time to see the planet’s waning crescent shape most clearly because Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened against the bright sky surrounding her. Good binoculars will show you Venus’ non-round shape, too. The planet itself will be growing a bit larger every day is it passes into the space between Earth and the sun, reducing our distance apart. At the latitude of Toronto, you might need to stand where Venus can be seen between buildings or trees, but observers at tropical latitudes will see Venus more easily – higher and in a darker sky.

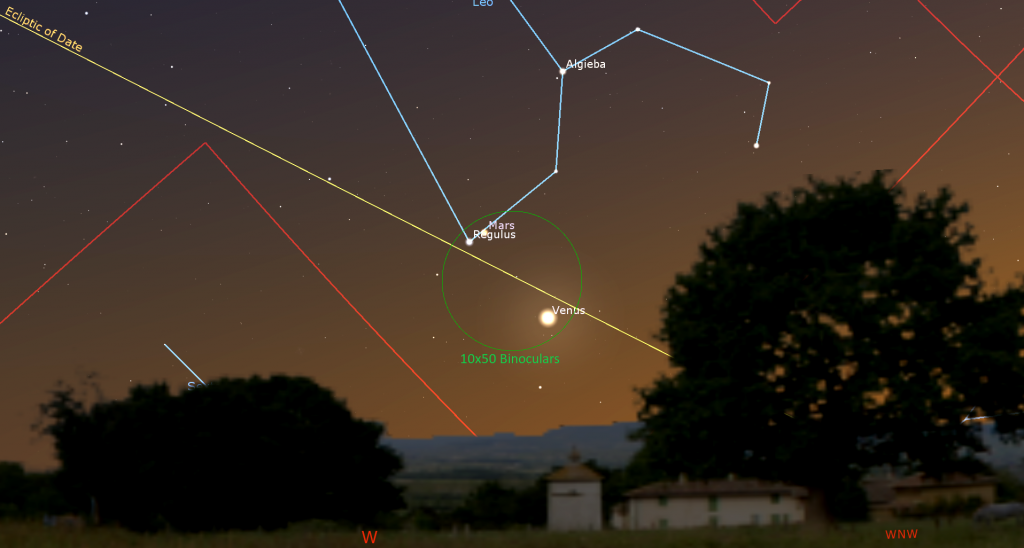

For some time now, the faint, reddish planet Mars has been following Venus across the sky and setting soon afterward. After dusk on Monday evening, Mars will be shining about four finger widths to the upper left of Venus, and less than a finger’s width above (or 40 arc-minutes to the celestial northeast) of Leo’s brightest star, Regulus. The red planet and the white star, which will appear slightly brighter than Mars, will share the field of view in a backyard telescope from Saturday to Wednesday. Each evening, Regulus will shift downwards and to the right, compared to Mars.

Once Venus sets at around 10:30 pm local time and Mars goes about half an hour later, we have less than an hour to wait for the next evening planet to appear. Saturn’s yellowish dot will rise over the eastern horizon at about 11 pm local time this week. That time will advance by 28 minutes per week, which means you’ll start catching sight of the ringed planet before bedtime in a week or two.

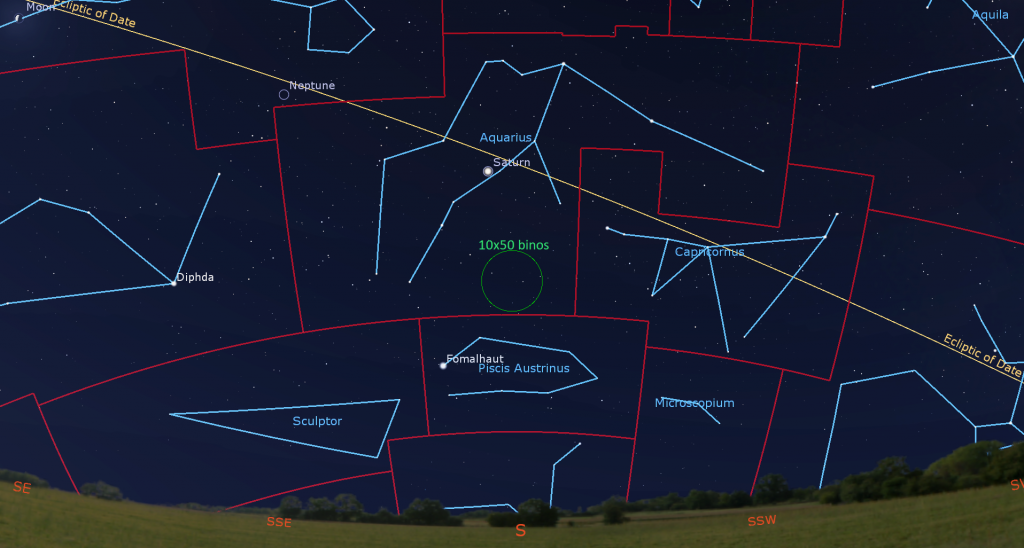

The best time to view Saturn in a telescope will be before dawn, when it will be located a third of the way up the southern sky. If you head outside before 5 am, you’ll be able to see the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) around Saturn. Look two fist diameters below Saturn for the very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish). That star, 18th brightest in the night sky, is only 25 light-years away. The James Webb Space Telescope recently imaged three dusty belts, or rings, surrounding it – evidence of violent collisions in its nascent planetary system. Here’s a link to the story on NASA’s site.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left (celestial east) of Saturn on Monday morning to the right (celestial west) of Saturn next Sunday morning. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the planet Neptune, 600 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 20° to its celestial east.

Bright, white Jupiter, which shines about 16 times brighter than Saturn, will rise next, at about 1:30 am local time. The stars of its host constellation Aries (the Ram) will shine a generous fist’s diameter above it. Jupiter will be easy to see in the southeastern sky until almost sunrise. Jupiter will become an evening planet by the second week of August. Then we’ll be able to view it after dinner until March, 2024.

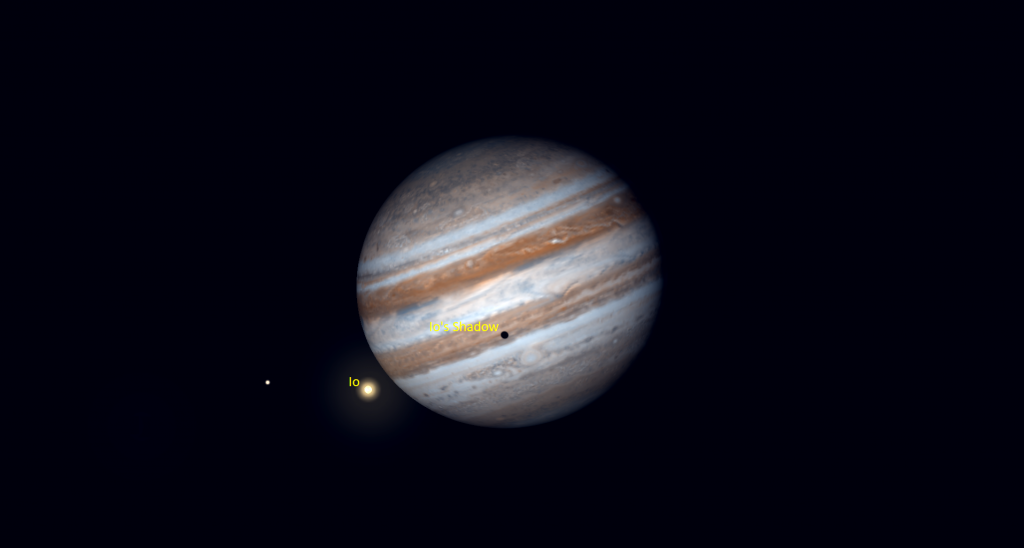

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter next Sunday morning. From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday morning, July 11, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter from 3:39 am to 5:44 am CDT (or 08:39 to 10:44 GMT) – a show best seen mid-continent time zones. On Thursday morning, July 13, Europa’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter from 3:42 am to 5:56 am EDT (or 07:42 to 09:56 GMT).

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Jupiter will be followed across the sky by Uranus, which will be positioned 1.2 fist diameters to the bright planet’s lower left (or celestial east) this summer. The magnitude 5.8, blue-green planet is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. It will become much easier to see in the coming weeks when it climbs higher. In the moon section above I highlighted some moon encounters with Jupiter and Uranus to catch this week.

Hercules on High

Moonless nights are ideal for viewing the sky’s best sights. On the next clear evening, head outside after dusk and point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith. While objects occupy that position, they always appear at their best because you are looking through the least amount of intervening air. The stars near the zenith barely twinkle for that reason. During late evening in July every year, the constellation of Hercules sits high in the southern sky, just below the zenith. And it contains some of the summer season’s best celestial “tourist attractions”!

Hercules’ stars aren’t overly bright, but you can still find it very easily, even from mildly light-polluted skies. Face southeast and look for a very bright, white star sitting fairly high in the sky. That’s Vega, the brightest star in Lyra (the Harp) and also brightest in the summer night sky. Another prominent star, orange-tinted Arcturus, will be shining lower than Vega and towards the west-southwest. Between these two stellar signposts is the realm of mighty Hercules. (By the way, a few weeks ago, here I declared that Vega and Arcturus are the first wishing stars of the evening.)

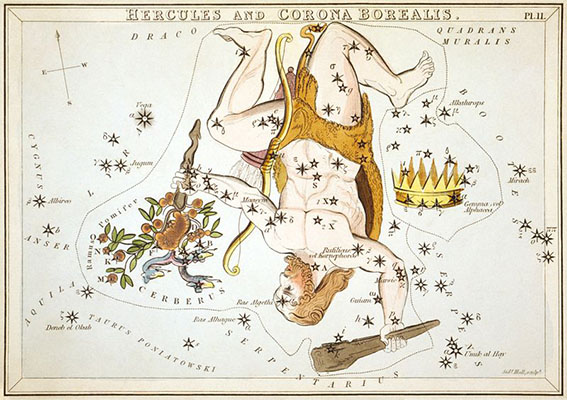

Hercules’ body is defined by a very recognizable keystone-shaped quartet of medium-bright stars. The keystone asterism is about 6° across (a palm’s width), with its wide end toward celestial north (upwards if you face south) and its narrow end pointed southwards (down). The hero of mythology is standing on his head for Northern Hemisphere observers. His sharply bent legs extend upwards (celestial north), and his two arms are outstretched downward (celestial south). The star that marks his eastern hand, named Maasym, or Lambda Herculis (λ Her), is to the lower left of the keystone. It connects to four other stars to form a loose chain of five stars running left-right, each separated by a couple of finger widths. In classical drawings of Hercules he is grasping the three-headed dog Cerberus, which he was tasked with capturing as one of his twelve labours. In other pictures, the chain of stars forms his arm, and fainter stars in southeastern Hercules are items he is grasping, such as a bough bearing the golden apples of the Hesperides or the two-headed dog Cerberus.

By the way, Hercules’ labours included slaying and skinning the Nemean Lion, killing the Lernaean Hydra, and capturing the Cretan Bull. Those three critters could be represented by the constellations Leo, Hydra, and Taurus. But only Leo (the Lion) shares the summer evening sky with Hercules. Taurus (the Bull) is setting in the west as Hercules climbs the eastern sky in springtime, with Hydra (the Snake) lurking below and between the two figures. In another story, the goddess Hera sent a crab to distract Hercules while he grappled with the Hydra. The crustacean was dispatched and became Cancer (the Crab). In Hercules’ 11th labour, he was to steal the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides, which were guarded by the hundred-headed Hesperian Dragon. That slain beast accompanies Hercules as the stars of Draco (the Dragon), his celestial neighbor to the north.

Hercules is the fifth largest constellation by area, and was one of the original 48 constellations tabulated in the Almagest, an early astronomy book produced in ancient Greece by Claudius Ptolemaeus (or Ptolemy). The early Greeks depicted Hercules, with his legs bent – as “The Kneeler” praying to his father Zeus to aid him in an upcoming battle. Beyond his feet, high in the northern sky, are the stars of Draco (the Dragon), ready to be crushed underfoot. To the lower right (or celestial west) of Hercules is the little circlet of stars that form the distinctive constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown). Arcturus sparkles even further off in the same direction.

Hercules’ location 30 degrees north of the celestial equator has allowed its stars to be seen everywhere on Earth except the southern tip of South America and Antarctica. Other cultures have formed patterns with the same stars. The indigenous Lokono or Arawak people of northern coastal South America call these stars Katarokoya (the Spirit of the Green Sea Turtle). The Ojibwe of North America used some of Hercules’ stars to form Noondeshin Bemaadizid (the Exhausted Bather) next to Madoodiswan (the Sweat Lodge), the stars of Corona Borealis.

Let’s tour Hercules. Starting in the keystone, the right-most and brightest star is designated Zeta Herculis (or ζ Her for short). The Stellarium app labels it Rutilicus. This is a binary star system situated about 35 light-years away from us, where the pair of stars orbit around one another. Both stars are yellow sun-like stars, although the brighter star is more massive and luminous. Moving clockwise and left, we arrive at the somewhat dimmer white star Epsilon Herculis (ε Her). Next, a palm’s width above Epsilon, is Pi Herculis (π Her), a cool, giant, orange-tinted star situated about ten times farther away from us than Zeta. At the upper right (celestial northwestern) corner of the keystone sits Eta Herculis (η Her). It is a yellowish, sun-like star, about ten times the diameter of the sun, but a bit cooler than our sun.

Hercules contains quite a few double and binary stars that are visible in a backyard telescope. One of the nicest ones is Rasalgethi, or Ras Algethi “Head of the Kneeler”. That medium-bright star is located about 1.6 fist diameters below (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Epsilon Herculis, near the border with Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Ophiuchus’ bright star Rasalhague sits a slim palm’s width to the left (east) of Rasalgethi. In a small telescope, Rasalgethi easily splits into a lovely pair of orange and greenish stars. The slightly brighter one is a red giant star that varies in brightness randomly over months to years. The fainter companion is a yellow, sun-like star that is itself a binary star too tightly spaced to resolve with a telescope. The stars are about 360 light-years away and are orbiting one another with a period of 3,600 years. This double star, like many others, was given a single name centuries before telescopes revealed that there was more than one star there.

The brightest star in Hercules, Kornephoros “Club-bearer”, sits a fist’s diameter below the keystone, where Hercules’ elbow would be. Only about two finger widths to the lower right (or 3° to the southwest) of Kornephoros is the double star Gamma Herculis (γ Her), sometimes named Nasak Shamiya III. It is another pair of stars that easily splits into two yellow stars when viewed in a backyard telescope. But this duo is a line-of-sight double star. The fainter star is actually much closer to us! Marsic or Marfik, which means “the Elbow” (even though it’s located at the end of Hercules’ western arm) is another “line of sight” double star that’s easy to view in a small telescope. Look for it about four finger widths to the lower right of Gamma.

Hercules’ legs are both bent. Look almost a fist’s diameter to the left (or 8° to the celestial east) of Eta Herculis to spot Theta Herculis, an aging orange giant star at the great distance of 750 light-years. Our hero’s eastern toes are marked by Iota Herculis, a blue-white star that shines about a fist’s diameter to the upper right of Theta. You can also find it by tripling the left side of the keystone. In 10,000 BCE, Iota was Earth’s pole star, and it will do so again around the year 15,500 AD!

Hercules’ more northerly, western knee is marked by blue-white Tau Herculis. It’s traditional Arabic name, Rukbalgethi Shemali means “Northern Knee”. It, too, will take a turn acting as Earth’s pole star in 18,400 AD. It is located almost a fist’s width to the upper right of Eta Herculis. The fainter star Sigma Herculis shines at the halfway mark to Tau. Hercules’ western shin and foot are the stars Phi and Chi Herculis, located to the lower right (celestial southwest) of Tau.

Hercules is positioned away from the summer Milky Way, so it isn’t as rich in deep sky objects as next-door Ophiuchus, Aquila, or Cygnus. But it does contain one of my favorite objects and a real summer crowd-pleaser, a globular star cluster known as the Great Hercules Cluster or Messier 13 (or M13). This object is a tightly packed ball of at least 300,000 old stars. At magnitude 5.9, it is visible with unaided eyes under dark skies as a faint smudge, but reveals much more under magnification! It is located along the western (right-hand) edge of the keystone, about one-third of the way from the wide end. Your binoculars should pick it up if the sky is fully dark. Midway between Hercules’ knees there is another, smaller globular cluster called Messier 92. This one is also readily visible in binoculars. A third, small and faint globular cluster designated NGC 6229 sits 6.5°, or a palm’s diameter, to the upper right of M92.

Globular clusters are one of the most interesting classes of objects for stargazers. These spherical concentrations of old, densely packed stars orbit in the region just outside our Milky Way galaxy, and we’ve observed many of them around other galaxies, such as the Andromeda Galaxy. Some of the clusters plunge through the disk of our galaxy from time to time. Viewed in a telescope under dark skies, they will look like a pile of salt poured onto black velvet – with a dense white center surrounded by a sprinkling of outlying stars. Each cluster looks different, varying in the density of stars from core to edge. Photographs reveal that these objects contain a mixture of reddish, blue, and yellow stars in different proportions.

The Great Hercules Globular Cluster was first observed by British astronomer Edmund Halley in 1714 and later included as number thirteen in Charles Messier’s famous list of “not-a-comet” objects. At 21,500 light-years away, it is a relatively close member of that class of objects. It shines with a relatively bright magnitude of 5.8, and it actually covers an area of sky spanning 20 arc-minutes (or two thirds of the moon’s diameter)!

More than 150 of these clusters have been mapped around our galaxy. They are so densely packed that the stars in their interiors are extremely close together, stirring the imagination of those contemplating extraterrestrial intelligent life. Advanced civilizations on planets around stars embedded deep inside a globular cluster would be able to exchange radio messages on timescales of weeks or months – and travel between adjacent solar systems would not require the decades or centuries we would need to visit our nearest neighbours. In fact, M13 was also one of the first targets for potential contact with other civilizations, when a radio message was beamed there from the Arecibo Radio Observatory in 1974.

The stars of Hercules are host to at least fifteen known exoplanets, including one named TrES-4. At 1.7 times the mass of Jupiter, it’s one of the most massive exoplanets yet discovered. However, its calculated density is extremely low, about the same as cork! This is one of the hot-Jupiter class of exoplanets, with a surface temperature in excess of 2,000 C.

If you own a large telescope, watch for the oval of the spiral galaxy named NGC 6207 positioned just 0.5 degrees to the north-northeast of M13. I also suggest looking at the small and very star-like, oval, blue coloured Turtle Nebula (or NGC 6210). It is a planetary nebula located 4 degrees NE of the star Kornephoros – in the direction of the star 51 Herculis. You could also aim your finderscope 1° more than twice the span between the stars Eta and Epsilon Herculis (i.e., the eastern side of the keystone). An Oxygen-III filter will highlight the nebula by dimming the surrounding stars.

If you are an astroimager or you own a really giant telescope, turn your attention to the sky just north of the midpoint between the 5th magnitude stars Marsic and r Herculis. A rich cluster of remote and faint galaxies are gathered there, including the interacting pair NGC 6050 and IC 1179, collective known as Arp 272. The pair are 450 million light-years from Earth! Prominent galaxies near them include NGC 6047, NGC 6042, and another embracing pair named NGC 6039 and NGC 6040 – to highlight just a few.

Let me know how your exploration of Hercules goes.

Some Moonlight-Friendly Sights

If you missed last week’s information about sights to see – with your unaided eyes, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes – when the moon is shining, I posted it here. They’ll be even easier to see this week!

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 1 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on an interesting topic in astronomy. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!