Maximum Mercury and Uranus, Earth’s Celestial Side-kick Leaves Evening, and November’s Brightest Lights!

This terrific image of Mars this week was taken by my friend Rick Foster at 1:43 am EDT on Sunday, November 1, 2020.

Hello, November Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of November 1st, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To see the pictures more clearly, right-click and save them to your computer, and to subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will shift into the post-midnight sky by week’s end, leaving evenings darker worldwide. Meanwhile, I offer you a tour the brightest stars of early November. Mars continues its splendid all-night showing, while Jupiter and Saturn only shine during early evening, and Mercury joins Venus before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

Did you remember to set your clocks back an hour after Halloween? With the end of Daylight Savings Time, we’re back to our regularly scheduled program of sunrises and sunsets. Your time zone abbreviation has changed, too. For example, 8 pm Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is now 7 pm Eastern Standard Time (EST).

For those of us in Toronto, the sun is rising at about 7 am EST and setting around 5 pm EST. The amount of daylight is decreasing by a whopping 2.5 minutes every day – or 18 minutes every week! The end of astronomical twilight, when the sun is far enough below the horizon for the sky to reach maximum darkness, ends at about 6:40 pm. As a stargazer, I do appreciate being able to pull out the telescope earlier – but I’m not a fan of the colder temperatures and the cloudier skies of November.

By the way, if you plan to use your telescope on chilly nights, place it in a secure spot outside, with the lens cap on, about an hour before you head out. That will give the air inside it a chance to equalize with the outside temperature – yielding sharper views through it. Before you bring it back in, put the lens caps back on to keep the optics from frosting up – or zip it into its case, if you have one. (Or snug a garbage bag around it while it warms to room temperature.)

Southern Taurids Meteor Shower Peak

Meteors from the Northern Taurids shower, which appear worldwide from September 23rd to November 19th every year, will reach its peak of about 10 meteors per hour on Thursday, November 5. The long-lasting, weak shower is derived from debris dropped by the passage of periodic Comet 2P/Encke. The larger-than-average grain sizes of that comet’s particles often produce colorful fireballs.

Although Earth will be traversing the densest part of the comet’s debris train during mid-day in the Americas, the best viewing time will occur hours earlier, at around 1 am local time, when the shower’s radiant, located in central Taurus, will be high in the southern sky. But don’t watch the radiant – meteors near it will have very short streaks because those meteors are heading directly towards you. Instead, get comfortable and find a safe, dark location with lots of open sky and just look up. And don’t bother with binoculars or a telescope – their field of view is too narrow. Unfortunately, a bright, waning gibbous moon will shine all night long, somewhat spoiling this shower.

While you are looking up, keep an eye out for early meteors of the Leonids shower. They’ll appear to be traveling from east to west across the sky. That shower will peak on November 17.

The Moon

Following Saturday night’s full Halloween moon, Earth’s celestial side-kick will shine brightly in the evening sky for observers all around the world for most of this week. But with the moon waning in phase and rising much later every night, darker evening skies will arrive with the coming weekend.

Tonight (Sunday), the still very full, gibbous moon will cross the overnight sky among the stars of Taurus (the Bull). On Monday night, the orbital motion of the moon will carry it closely above the Hyades star cluster. That’s the collection of stars that form the triangular face of Taurus. The bright, orange star Aldebaran, which marks the southern eye of the bull, will sit several finger widths below (or 4 degrees south of) the moon. To better see the Hyades’ stars, many of which are double stars, hide the bright moon just above your binoculars’ field of view.

On Wednesday night, the moon will rise among the stars of Gemini (the Twins). It will be positioned less than a lunar diameter below (or half a degree to the celestial south of) the large open star cluster designated Messier 35, or the Shoe-Buckle. During the rest of the night, the moon’s orbital motion will continuously draw it away from the cluster. To better see the cluster’s stars, wait until they are higher in mid-evening, and then hide the bright moon just below the field of view of your binoculars. This cluster is small enough to view in a telescope, too.

On Friday and Saturday night, the much less illuminated moon will spend time among the dim stars of Cancer (the Crab). The moon will end this week exhibiting its last quarter phase, which will occur at 6:46 pm EST on Sunday, or 13:46 Greenwich Mean Time. At last quarter, the moon always rises at around midnight, and then remains visible in the southern daytime sky all morning – leaving our evenings deliciously dark!

The Planets

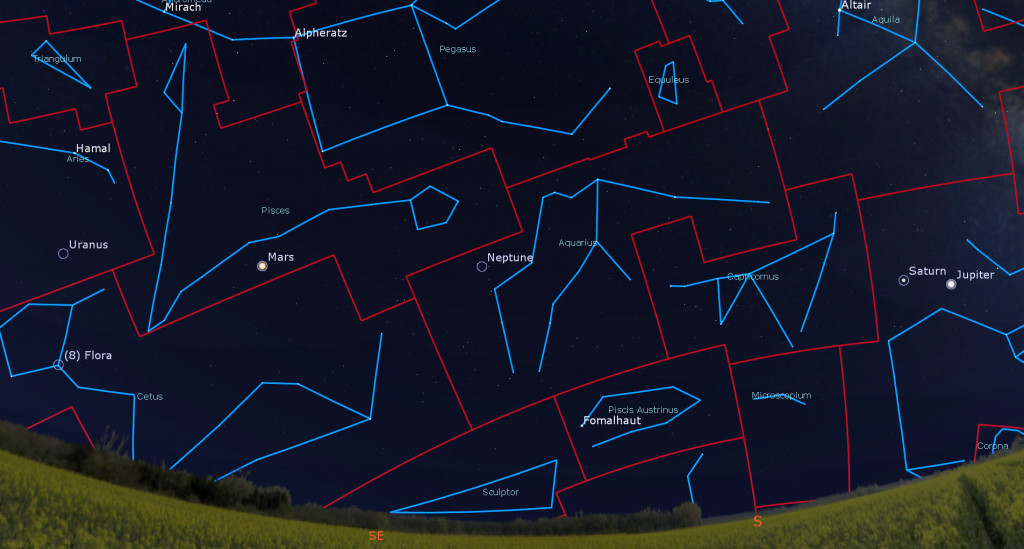

Well before 6 pm local time this week, very bright, white Jupiter will become visible in the lower part of the southern sky. A short time after that, dimmer, yellowish Saturn will appear a slim palm’s width to Jupiter’s upper left (or 5 degrees to the celestial east). Faster Jupiter is chasing slower Saturn, and they’ll pair up in spectacular fashion on December 21! Our season of clear views of those two planets is almost over. After 8:30 pm in your local time zone, they will be getting low in the southwestern sky, and shining through a much thicker blanket of Earth’s atmosphere. You might even see them twinkle a bit in late evening! Thankfully, the earlier sunsets are allowing us to start viewing them earlier each night.

Good binoculars should show you the four large moons that Galileo Galilei discovered beside Jupiter in January, 1610. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, they dance around the planet from night to night – although one or more can be hidden by Jupiter at any given time. If the air is steady, even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown bands and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short). Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour rotation period, the GRS will be visible every second or third night at your location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday.

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. On Sunday, November 1 from 5:35 pm (dusk in the Eastern Time Zone) to 9 pm EDT, Ganymede’s large shadow will travel across Jupiter. The event will be visible anywhere on Earth where Jupiter is above the horizon during the time windows (adjusted to your local time zone). Other places will see different transits.

Saturn is a spectacular sight. Any backyard telescope will show you Saturn’s rings. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

Your telescope should also reveal several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. The trick for seeing more moons is to watch continuously for a minute or two, and let the dimmer, closer-in moons appear whenever the air stabilizes. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the left of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.) Fun fact: There’s a Mount Doom on Titan!

Thankfully, Mars is still a great evening and late-night target! This week, very bright, reddish-tinted planet will already be climbing the lower part of the eastern sky once it’s dark out. Mars will climb to its highest point – and best viewing position, a bit more than half-way up the southern sky – at about 10:30 pm local time. Then it will set in the west before sunrise. Viewed in a telescope this week, Mars will display the dark Mare Erythraeum, Sinus Sabaeus, and Aurorae Planum regions wrapped around its middle, and the bright, adjacent Chryse region.

Because Earth is passing Mars on the “inside track” of the solar system, Mars is moving retrograde, causing the planet to appear to travel westward compared to the narrow “V” of modest stars at the bottom of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). You won’t see that motion unless you carefully note the positions of Mars and the surrounding stars changing over several nights.

Blue-green Uranus reached opposition and best visibility for 2020, yesterday (Saturday). On that night it was closest to Earth for this year – at a distance of 2.81 billion km, or 156 light-minutes. Its minimal distance from Earth will cause it to shine at a peak brightness of magnitude 5.7 and to appear slightly larger in telescopes, during the weeks surrounding opposition. Uranus is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. For context, that region of the sky is two fist diameters to the left (or 22° to the celestial east) of Mars. Try for Uranus after mid-evening, when it will be higher in the sky. I posted a detailed star chart for Uranus here.

Neptune, which rises in mid-afternoon, is located among the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), about two finger widths to the left (or 2 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, Neptune will already be in the lower southeastern sky after dusk. Then it will climb higher until 8:45 pm local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s almost halfway up the southern sky. I posted a detailed sky chart for Neptune here.

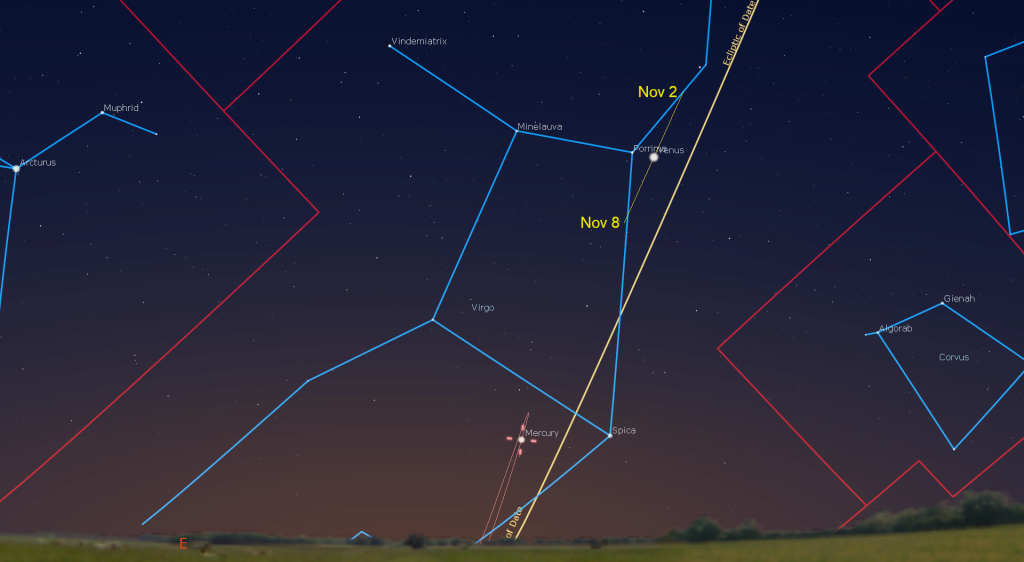

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now. It will rise at about 4 am local time this week, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a gibbous, football shape. This week, the planet will be traversing the stars of Virgo (the Maiden). Venus will sit just a finger’s width to the right (or 1 degree to the celestial south) of that constellation’s bright double star Porrima on Thursday morning. Venus is shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will allow it to shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until early December!

For Northern Hemisphere observers, November will offer an excellent opportunity to view Mercury in the eastern pre-dawn sky; but it will be a poor apparition for those located near the Equator and farther south. You can look for the speedy planet sitting very low over the east-southeastern horizon, a bit to the left of Venus, starting on Monday morning after 6:45 am. But each morning after that, Mercury’s position north of the steep morning ecliptic will allow skywatchers to see the planet more easily – and shining in a dark sky. Next Tuesday, Mercury will reach a maximum angle from the sun, and peak visibility. Be sure to stop using binoculars to search for Mercury well before the sun rises!

The Brightest Stars of November

With November now here, the brightest constellations of the year have returned to the evening sky. Many of them contain two or more very bright stars. Meanwhile, quite a few of the bright summer stars are still around – mainly because the earlier sunsets are keeping them in view even as they shift towards the sun. Some call this “the Summer Triangle effect”. (Every spring, the later sunsets shorten our viewing time for the arriving spring constellations – and the galaxies that they host.)

Bright stars are easy targets on moonlit nights, even under mildly light-polluted skies. Once Sirius rises in the east-southeast at about 11:20 pm local time, six of the top ten brightest stars in the entire night sky become visible to observers at mid-northern latitudes worldwide. Let’s tour the brightest stars. (I’ve put their brightness rankings in parentheses – not counting the sun.)

Even before the sky has fully darkened this week, look low over the western horizon for orange-tinted Arcturus (4th) in Boötes (the Herdsman). The bent handle of the Big Dipper, which sits low in the northwestern sky after dusk, “arcs to Arcturus”. Arcturus’ name comes from the phrase “follower of the bear” because it chases Ursa Major (the Big Bear) around the sky – and it shares a root with the word “arctic”.

The three bright, white stars of the Summer Triangle are higher in the western sky. They’ll actually continue to be visible until mid-January! During mid-evening, very bright Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Harp) will be about halfway up the western sky. Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle) will be slightly lower and off to Vega’s left (or celestial south) – preparing to set at about the time when Sirius rises. You’ll find Deneb (19th) in Cygnus (the Swan) more than two fists above and between the other triangle stars.

Turning to face south, mid-northern latitude observers with a low southern horizon should be able to see Fomalhaut (18th) in Piscis Austrinus (the Southern Fish). Big telescopes have been able to take pictures of a dusty protoplanetary disk that encircles Fomalhaut. People living at more southerly latitudes get to see Fomalhaut higher in their sky.

The rest of the brightest stars are in the eastern sky after mid-evening. Yellowish Capella (6th), in Auriga (the Charioteer) is the brightest and highest of the eastern sky’s bright lights. Although it is circumpolar (i.e., it never sets), it doesn’t tend to climb higher than landscape obstacles until about 6 pm local time. Reddish Aldebaran (14th), which marks Taurus the bull’s southern eye, is located three fist diameters to the lower right (or 30 degrees to the celestial south) of Capella. It’s rising at about 7 pm local time this week.

The next bright star to rise, at about 9 pm local time, will be orange-red Betelgeuse (normally 10th). This red giant marks the eastern shoulder, or armpit, of Orion (the Hunter). Last winter Betelgeuse dimmed dramatically, lowering its ranking for a while. (Orion’s other shoulder star Bellatrix ranks 26th.)

The next bright November star to rise is Pollux (17th), which marks the head of the eastern (and lower) sibling of Gemini (the Twins). Pollux is positioned about 3.4 fist diameters below (or 34 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Capella. The star sitting about four finger widths above Pollux is Castor (24th). To help you remember which is which, note that Castor comes first in an alphabetical list and also rises before Pollux.

Fifteen minutes later, blue-white Rigel (7th), which marks the western foot of Orion, will appear over the east-southeastern horizon. Then we have to wait 90 minutes for the next bright star to appear – Procyon (8th), in Canis Minor (the Little Dog). It’s below and between Gemini and Orion.

Our last bright stars to rise are part of Canis Major (the Big Dog). The “Dog Star” Sirius (1st) will be hard to miss once it rises at about 11:20 pm local time. The star will climb to its highest point, about a third of the way up the southern sky, at 4 am local time. If you are walking through your darkened house in the middle of the night, this star might catch your eye out a south-facing window because it never climbs very high. Sirius’ brightness and low position in the sky combine to produce spectacular flashes of colour as it twinkles. Finally, at 12:30 am, the star Adhara (22nd) will appear below Sirius. Adhara marks the dog’s rear leg and gives this little constellation two bright stars.

Stars shine brighter for two primary reasons. They can be inherently more luminous (i.e., emitting more visible light) and/or they can be closer to us. Two of the stars noted above, Sirius and Procyon, are only about 10 light-years away from our sun. Vega, Altair, Pollux, and Fomalhaut are less than a few dozen light-years away. Betelgeuse is 640 light-years away. Amazingly, Deneb is a whopping 2,600 light-years away! It’s producing a prodigious amount of visible light to appear so bright from such a distance!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Monday, November 2 at 7 pm EST, the Toronto Public Library will broadcast a fascinating conversation between two amazing woman astronomers – M.I.T.’s Dr. Sara Seager and Dr. Renee Hlozek. They’ll be discussing Dr. Seager’s new memior The Smallest Lights in the Universe. Details and the registration link are here.

On Monday, November 2 at 1:30 pm EST, The Origins Institute at McMaster University invites you to a free public lecture with Dr. Kailash C. Sahu, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, and an instrument scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope. His topic is A Census of Exoplanets in the Milky Way through Gravitational Microlensing. Details and the Zoom link are here.

Our David Dunlap Observatory Saturday night events may be suspended at the moment, but we’re still pleased to offer the next best thing – free online talks via YouTube! On Saturday, November 7 at 7:30 pm EST, join us for DDO Astronomy Night: Unravelling the Mysterious Fast Radio Burst with CHIME. Dr. Cherry Ng from the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics will describe how Canada’s CHIME radio telescope is helping us understand the distant Universe. More information can be found here, and the channel is https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, November 17 – with the topic TBD. (Send us suggestions!) You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here. Don’t forget to tune in to Jenna and John Reid’s final RASC Explore the Universe certificate livestream on Thursday, October 29 at 3:30 pm EDT.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!