Maximum Meteors on Monday, the Old Moon’s Crescent Covers a Star, Medusa’s Eye Gleams, and some Binoculars Delights

The Double Cluster in northwestern Perseus makes a fantastic target for binoculars at this time of year. This wide field image was taken by Volker Wendel and was NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day on December 7, 2007.

Hello, October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 20th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where all the old editions will be archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

For those who have been reading my Skylights on Tumblr, I have migrated the content to my website, where I can better control the size of the photos and sky charts. The page where the Skylights are listed is located at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/. We’re still perfecting the site, so let me know if you have any comments or suggestions.

The bright evening planets are beginning to “exit – stage west” now. The moon will be absent from the evening sky worldwide as it swings towards the pre-dawn sun. So it’s a great time to explore the fall-winter deep sky treasures with binoculars and telescopes – while temperatures are still mild. Meanwhile, Earth’s nearest planets, Venus and Mars, are both improving in visibility as they increase their angles from the evening and morning sun, respectively. And Mercury has reached peak visibility, too. Here are your Skylights!

The Moon and Planets

Tonight (Sunday) the waning moon will rise in the east at about 11:30 pm local time. It will look half-illuminated because the moon will reach its last quarter phase on Monday morning. At its last quarter phase, the moon always rises around midnight and remains visible in the southern sky until early afternoon. Like first quarter moons, the last quarter moon is gorgeous under magnification – but you have to be willing to rise before dawn to enjoy it!

Over the first part of this week, the moon will rise in the wee hours and traverse the stars of Gemini (the Twins) on Sunday and Monday, then dim Cancer (the Crab) on Tuesday, and bright Leo (the Lion) on Wednesday and Thursday.

When the moon rises in the eastern sky after shortly before 1 am EDT on Tuesday, it will be completing a passage through the heart of the large, open star cluster known as the Beehive (and Messier 44). The moon’s orbital motion will carry it several degrees away from the cluster by dawn, but both objects will still fit within the field of view of binoculars. For best results, position the moon outside of the lower left of your binoculars’ field of view and look for the cluster’s myriad stars. Hours earlier, observers in Europe and Asia can witness the moon crossing just north of the cluster’s center.

On Friday morning, the old crescent moon will rise at about 4:30 am local time and enter the constellation of Virgo (the Maiden). As it does so, the moon will pass in front of (or occult) a medium-bright star named v Virginis, or 3 Virginis. You can watch the event in a telescope, through binoculars, or with your unaided eyes. At about 5:28 am Eastern Daylight Time (or 09:58 GMT), the bright crescent of the moon will cover the star. At 6:21 am, the star will suddenly re-appear over the dark top edge of the moon. During these lunar stellar occultation events, stars disappear and reappear almost instantly because the moon has no atmosphere to spread out a star’s narrow beam of light. The exact timings will vary by your latitude, so start watching earlier – or use an astronomy app like SkySafari to find out the exact times where you are located. By the way, the moon’s orbital motion around Earth is fast! The moon shifts by its own diameter every hour.

In the eastern sky on Saturday morning, the slim, old, crescent moon will be positioned a palm’s width above (or to the celestial northwest of) the reddish planet Mars. Try to look for them between about 6:30 and 7 am local time.

Next Sunday morning, you might catch a glimpse of the very slim crescent moon sitting just above the eastern horizon before sunrise. Interestingly, the moon will reach its new moon phase just before midnight Eastern Time on Sunday evening. At its new phase, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon will be completely hidden from our view until just after sunset on Monday evening.

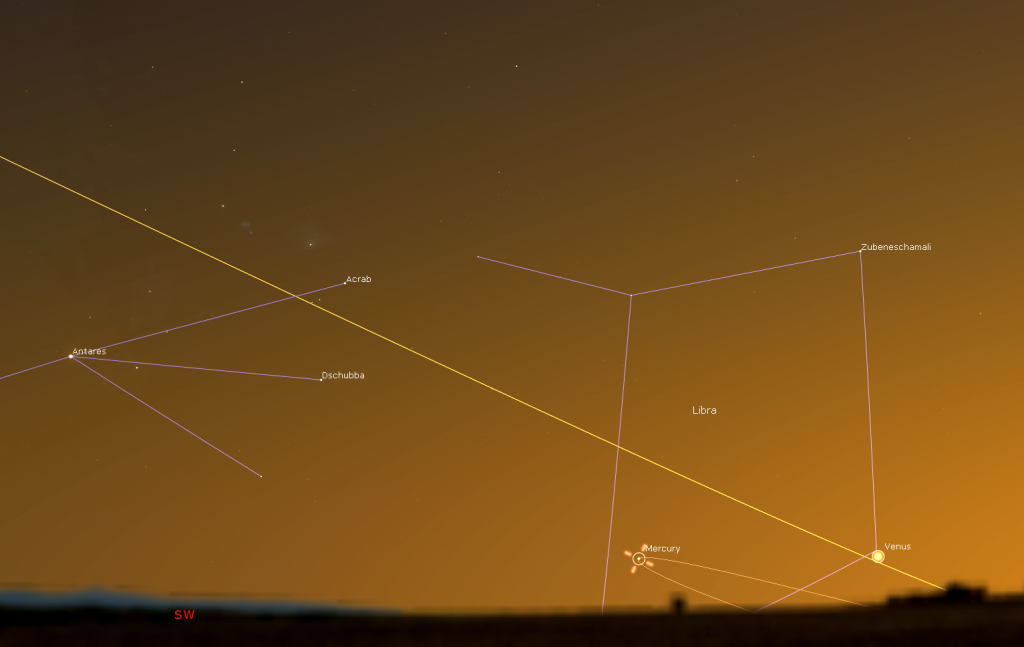

Mercury and Venus will continue to occupy the western, post-sunset sky this week. Venus continues to shift farther from the sun, but the shallow evening ecliptic will prevent Venus from climbing above the glare of sunset for a while longer. Venus’ bright magnitude -3.85 brilliance will make it fairly easy to spot for a brief period after sunset, if you can find a low open horizon to the west-southwest. It sets shortly after 7 pm local time.

On the evening of Sunday, October 20, Mercury will reach its widest separation (25 degrees east) from the sun for the current apparition. With Mercury south of a shallowly dipping evening ecliptic, this has been a poor appearance of the planet for Northern Hemisphere observers, but an excellent one for those at more southerly latitudes. The optimal viewing period for mid-northern latitudes will fall between 6:45 and 7 pm local time.

You can use Venus to find comparatively dimmer Mercury. Because Mercury has reached its greatest separation from the sun, and Venus has not, Venus will be shifting closer to Mercury this week. Tonight Mercury will be positioned a generous palm’s width to the left (or celestial southeast) of Venus. Next Sunday, however, Venus will have moved to within four finger widths to the upper right of Mercury. Viewed in a telescope this week, Mercury will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. (Venus will look almost fully illuminated.)

Jupiter will be setting in the west at about 9 pm local time this week, but the earlier-arriving sunsets of October are still giving us time to view the spectacularly bright planet, albeit through a LOT of intervening atmosphere. Still – time is running out for Jupiter-viewing this year. As the sky begins to darken this week, look for the giant planet sitting about 1.5 fist diameters above the southwestern horizon. Jupiter has spent this entire year below the stars of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) and above Scorpius (the Scorpion). It will spend next year sitting quite close to Saturn!

On a typical night, even a backyard telescope will show you Jupiter’s two main equatorial stripes and its four Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede looking like small white dots arranged in a rough line flanking the planet. Good binoculars will show the moons, too! If you see fewer than four dots, then the missing ones are in front of Jupiter, or hidden behind it. Or, it might be that some moons are not being illuminated by sunlight because they are in eclipse!

Yellow-tinted Saturn is still a very good option for backyard telescopes. It’s in the southern evening sky – and is rather less bright than Jupiter. The ringed planet will be visible from dusk, when it will be about 2.5 fist diameters above the southern horizon, until about 10:30 pm local time. Saturn’s position is just to the upper left (or celestial east) of the stars that form the teapot-shaped constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer) and about 2.5 fist diameters to the upper left (or celestial east) of Jupiter.

A look at Saturn is well worth dusting off your old telescope! Once the sky is dark, even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons, especially Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper left of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the lower right of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will flip the view around.)

The ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune are both positioned more-or-less opposite the sun in the sky, so each one is a good all-night target.

Distant and dim, blue Neptune is visible all night long among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and is less than a finger’s width to the right (or celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. Both blue Neptune and that golden-coloured star will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at medium power. The distance between the star and the planet is steadily increasing due to Neptune’s westward retrograde orbital motion. I posted a diagram of Neptune’s position compared to that star here.

Blue-green Uranus will be rising in the east at sunset this week. It will remain visible all night long because it is only a couple of weeks ahead of its annual opposition date – when it will appear at its closest and brightest for 2019. The planet is sitting below (or to the celestial south of) the stars of Aries (the Ram) and is just a palm’s width above the circlet of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Whale). At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is actually bright enough to see in binoculars and small telescopes, under dark skies. You can use the three modest stars that form the top of the head of the whale (or sea-monster in some tales) to locate Uranus for the next several months – because the distant planet moves so slowly in its orbit. To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here.

Mars is still pulling away from the sun’s glare in the eastern pre-dawn sky. It rises at about 6:10 am local time and will become more easily visible in early November. Unfortunately, the red planet is on the far side of the sun from us – so it will remain rather small and faint until early next year.

Binocular Dark Night Delights

The next two moonless weeks will be ideal for seeing the deep sky gems scattered along the winter Milky Way – and more. Here are some suggestions for binoculars viewing that are bright enough to see, even near city lights.

In mid-evening during late October, the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) is positioned midway up the northeastern sky. This constellation’s location straddling the outer reaches of the Milky Way has filled it with rich star clusters. The largest of these clusters, named Melotte 20, surrounds the bright star Mirfak, or Alpha Persei. Also known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group and the Perseus OB3 Association, the cluster is a collection of about 100 young, massive, hot B and A-class stars spanning 3 degrees (or six full moon diameters) of the sky. The cluster can be seen with unaided eyes, and improves in binoculars. It is approximately 600 light years from the sun and is moving through the galaxy as a group. Mirfak is moving with them. That elderly, yellow supergiant star has evolved out of its blue-coloured phase and is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen in its core.

The northwestern region of Perseus contains the well-known Double Cluster. Two bright, open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and only 0.45 degrees apart, form a spectacular sight covering a single finger’s width of sky. If you face northeast, they will be located midway between W-shaped Cassiopeia (the Queen) and the bright star Mirfak.

You can try to see the pair of clusters without help. They’ll look like two fuzzy patches. Or use binoculars or a low power, widefield telescope to view them in all their glory. The lower, more westerly cluster is also known as NGC 869. It is more compact and contains more than 200 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the higher, easterly cluster, is slightly more spread out. Both clusters reside in the Perseus Arm of our Milky Way galaxy and are located about 7,300 light-years from the sun. Their region of the sky is heavily loaded with opaque interstellar dust that extinguishes their intensity.

An extra-galactic treat is nearby. After dusk on October evenings, the Andromeda Galaxy is halfway up the eastern sky. This large spiral galaxy, also designated Messier 31 (or M31), lies a whopping 2.5 million light years from us, and subtends an area of sky measuring 3 by 1 degrees (or six full moon diameters across and two diameters high). Under dark skies, the galaxy can be seen with unaided eyes as a faint smudge to the left (or celestial northeast) of the square of Pegasus (the Horse). The three westernmost stars of Cassiopeia, Caph, Shedar, and Navi, conveniently form a triangle that points towards the galaxy. Binoculars will reveal the galaxy better. In a telescope, use low magnification and look for the two smaller companion galaxies Messier 32 close to M31’s core and Messier 110, which is farther from the core on the opposite side.

Later in the evening, you can look for the bright little star cluster known as the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, and Subaru (in Japan). It will rise from the north-northeastern horizon after 8 pm local time.

Watch the Demon star Brighten

The “Demon Star” Algol in Perseus (the Hero) is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably for about 10 hours once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star. Once the eclipse begins, the star steadily drops in brightness for five hours, and then it ramps up again during the second five hours – until the eclipse is over.

Algol represents the glowing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying. That’s why this star has the nickname the “Demon Star”. Perseus is positioned to the upper left of the bright Pleiades star cluster. Another name for Algol is Gorgonea Prima “the First Gorgon”. The star that sits two finger widths to the right of Algol is Gorgonea Tertia “the Third Gorgon”. By the way, Gorgonea Secunda “the Second Gorgon” and Gorgonea Quarta “the Fourth Gorgon” are the stars Pi () Perseii and Omega () Perseii. They sit to the upper right and lower right of Algol, respectively. The four Gorgons stars combine to form Medusa’s box-shaped head.

On Friday, October 25 at 8:51 pm EDT, Algol will reach its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4 (i.e., the smaller, dimmer star will be fully in front of the larger, brighter star). At that time, Algol will be positioned a third of the way up the northeastern sky. By 1:51 am EDT, Algol will be approaching the zenith and will have brightened to its usual magnitude of 2.1.

The easiest way to detect Algol’s variability is to note how bright Algol looks compared to other neighboring stars. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol is brighter than any other nearby star save Mirfak, which sits a fist’s diameter to Algol’s left (or celestial north). Although Gorgonea Tertia is somewhat variable, too, it shines at about the same brightness as Algol when Algol is at minimum.

With the early sunsets of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, we’ll have many chances to see Algol brighten at convenient times – say, from dinnertime to bedtime. I’ll alert you to the best opportunities in future Skylights.

Orionids Meteor Shower

The excellent Orionids Meteor Shower, which is derived from fine particles dropped by repeated past passages of Comet Halley, runs from September 23 to November 27, and is observable world-wide. The Orionids (for short) will peak in the hours between midnight and dawn (in your local time zone) on Tuesday, October 22. At that time, the sky overhead will be plowing through the densest region of the particle field, generating as many as 25 meteors per hour.

This shower has a broad period of activity – the comet’s debris field is very spread out because the comet’s orbit crosses Earth’s at a shallow angle. While the Orionids will linger until late November, they will decrease in quantity every night after this week’s peak.

The meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but true Orionids will be travelling in a direction away from a location in the sky called the radiant. It’s positioned a fist’s diameter to the upper left of the bright red star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion, which gives this shower its name.

Although not too numerous, Orionids are known for being bright and fast-moving. Unfortunately, the waning, half-illuminated moon will overwhelm the weaker meteors on the peak nights this year. You can watch for meteors on Monday before midnight, too – but many of them will be obscured by the Earth’s horizon.

To see the most meteors, get away from light-polluted urban skies and find a dark site with plenty of open sky. Don’t bother with binoculars or a telescope – their fields of view are too narrow for meteors. And don’t watch the sky near the radiant – those meteors will be travelling towards you and will produce very short streaks. Just keep your eyes on the sky overhead.

You can start watching as soon as it is dark, or head outside before the dawn twilight begins. Avoid bright white light from phones or tablets – it will spoil your eyes’ dark adaptation (red light is fine). If the peak night forecast calls for clouds, try the nights before or the nights after. Happy hunting!

Bright October Stars

If you missed last week’s note about learning the brightest stars for this time of year, I posted a sky chart here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Registration and details are here.

Weather permitting, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory will host a free, public Orionids Meteor Shower viewing session on Monday evening, starting at 8 pm. The back-up date is Tuesday. Details are here.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, October 23, the RASC Toronto Centre will hold their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting at the Ontario Science Centre, and the public are welcome. This month, the speaker will be Dr. Isaac Smith, Assistant Professor, Planetary Science & Canada Research Chair, York University. His topic will be A High Resolution View of Icy Mars. Check here for details. Parking is free.

On Wednesday evening, October 23 at 7 pm, the Perimeter Institute in Waterloo will present a free public talk and webcast by Professor Gabriela González. She will speak about LIGO and Gravitational Wave Astronomy. Registration and details are here.

The last RASC-hosted Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for 2019 will be on Saturday, October 26. There will be sky tours in the Skylab planetarium room, space crafts, a tour of the giant 74” telescope, and viewing through the 74” and lawn telescopes (weather permitting). The doors will open at 7 pm for a 7:30 pm start. Attendance is by tickets only, available here. If you are a RASC Toronto Centre member and wish to help us at DDO in the future, please fill out the volunteer form here. And to join RASC Toronto Centre, visit this page.

This Fall and Winter, spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday afternoon, November 10, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older, and the Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!