Moon Moves Post-midnight, Perusing Planets in Evening, and Diving into Diminutive Delphinus!

This gorgeous scene captures summer nights in Canada. It was taken by my friend Kerry-Ann Lecky Hepburn on April 23, 2022. While autumn will soon arrive, its earlier sunsets will allow us to continue to view the Milky Way’s treasures for some time to come. The pink patches in this image are nebulas. They are visible as prominent, grey, fuzzy patches in your binoculars, when viewed from a dark site free from light pollution. Enjoy much more of Kerry-Ann’s terrific work at her website, www.weatherandsky.com

Hello, end-of-summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 11th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The bright moon will wane towards third quarter this week, vacating evening and lingering into morning skies worldwide. Meanwhile it will also pass several planets. All the outer planets are now observable in evening, although some do rise late. The darkening night sky will let us appreciate the late-summer constellations, including one of my favorites, tiny Delphinus. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

For the first few evenings of this week, the harvest moon effect will continue to attract worldwide attention above the eastern horizon after sunset. That’s because the waning gibbous moon will be rising only about 20 minutes later day. I wrote about the phenomenon last week here. After mid-week, though, the moon will be separated enough from the sun to become absent from the early evening sky – allowing those summer Milky Way sights to be enjoyed. That increased angle from the sun will also allow the moon to linger ever longer into the morning daytime sky this week – like an echo of midnight.

Tonight (Sunday) after mid-evening, the bright, 96%-illuminated moon will shine at bright Jupiter’s lower left among the northernmost stars of Cetus (the Whale) – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. As the moon chases Jupiter across the sky overnight, the moon will swing above Jupiter. Skywatchers viewing the duo later, or in more westerly time zones, will see the moon a little farther from the planet due to the moon’s continuous easterly orbital motion.

On Monday and Tuesday night the moon will be surrounded by the muted stars of Pisces (the Fishes), Cetus (the Whale), and Aries (the Ram). Look for the Ram’s two bright stars Hamal and Sheratan above the moon on Tuesday.

Starting late on Wednesday evening in the Americas, the blue-green, magnitude 5.7 speck of Uranus will be positioned a few finger widths to the upper right (or 3.9 degrees to the celestial west) of the waning gibbous moon – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. Messier 45, commonly known as the Pleiades star cluster will shine off to the moon’s left (east). The moon and Uranus will rise in the east-northeast after 9:30 pm local time, and then climb high into the southern sky before dawn. By then the easterly orbital motion of the moon will shift it farther from Uranus. Hours earlier, observers in much of Northern Africa, Europe, parts of the Middle East, and western Russia can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) Uranus around 21:30 Greenwich Mean Time – the ninth in a series of consecutive lunar occultations of that planet.

On Thursday night, the moon will shine among the stars of Taurus (the Bull), and binoculars-close below the Pleiades. Watch for the bright, reddish dot of Mars to their lower left (or celestial east) after midnight. When the pretty, half-illuminated moon rises in the eastern sky just before 11 pm local time on Friday, it will be positioned several finger widths to the left (or 3.5 degrees to the north-northeast) of Mars. They’ll remain cosy enough to share the view in binoculars through most of the night while the moon’s easterly motion pulls it farther from the planet.

The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Saturday at 5:52 pm EDT and 2:52 pm PDT or 21:52 GMT. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon always appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time, and then remain visible until it sets in the western daytime sky in early afternoon. The week of dark, moonless evening skies that follow this phase are the best ones for observing fainter deep sky targets. The moon will remain within the bounds of Taurus (the Bull) on Saturday night, and then hop into Gemini (the Twins) to end the week.

The Planets

If you skipped past my section on the moon (above), note that the bright moon will visit Jupiter, Uranus, and Mars on Sunday, Tuesday-Wednesday, and Friday, respectively. Let’s see what else the planets will be up to.

This week, Mercury will be too close to the setting sun to be seen, unless you live near the tropics. Meanwhile, very bright Venus will be visible, with a bit of difficulty just above the eastern horizon before sunrise. Both planets are swinging sunward for a solar conjunction, after which they’ll trade places – with Mercury entering the morning sky and Venus shining in evening. Never fear, though – there are plenty of planets to peruse!

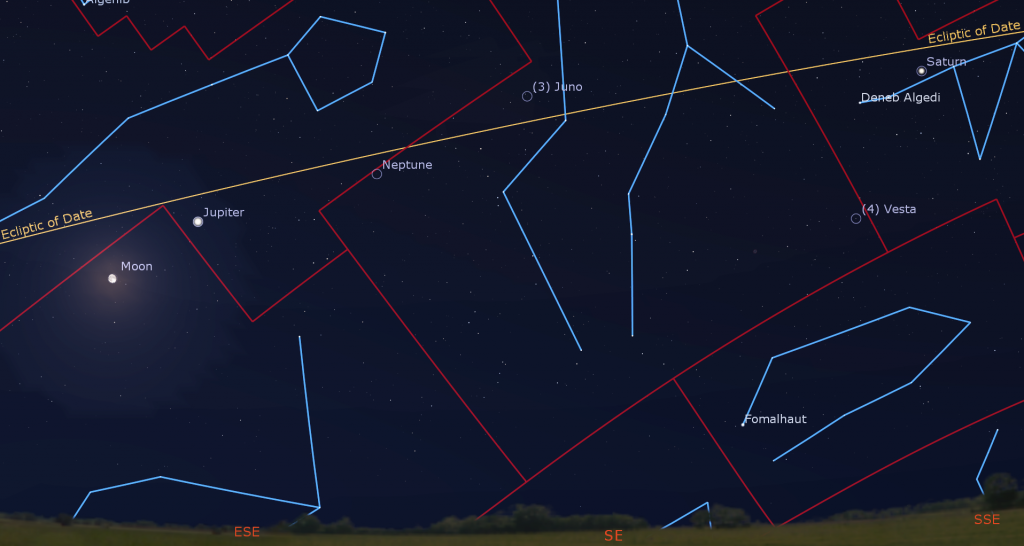

The medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn should become visible in the lower part of the southeastern sky before 8:30 pm local time. The ringed planet will be creeping slowly westward across the medium-bright stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) until late October. Saturn will cross the sky all night and set in the west-southwest before 4:30 am local time. Since the planets always look their best in a telescope when they are higher in the sky, Saturn’s peak viewing time will be around 11 pm, when it will shine in the south – but you can enjoy less-than-perfect views from dusk onwards. That peak window will shift earlier by half an hour with each passing week.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its rings, which will become more edge-on to us every year until the spring of 2025. This year Saturn’s southern polar region has already extended well beyond the ring plane. See if you can see the Cassini Division, the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its bright outer one. Over the coming weeks, Saturn’s slide to the west of the anti-solar point will cause the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. Where you find the shadow will depend on how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it’s toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be towards lower right. An equatorial mount will also rotate things a little. Take long looks and wait for moments of perfect clarity.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower left (or celestial east) the planet tonight (Sunday) to the upper right (or celestial west of) the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

This week, extremely bright, white Jupiter should clear the eastern rooftops by around 9 pm local time, and then spend the night shining among the modest stars of Pisces (the Fishes), following 17 times fainter Saturn across the sky. Jupiter will climb highest at 2 am, but it will look reasonably good in any telescope after 10 pm local time. Early risers can spot the planet descending the southwestern sky before sunrise.

Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, which complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four of them, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter – or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth hours, we can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pale-looking Great Red Spot cross the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Sunday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday evening, and also during the wee hours of Tuesday, Wednesday (with Europa’s black shadow), Friday, and Sunday morning. The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. Europa’s tiny shadow will cross Jupiter with the Great Red Spot on Wednesday morning from 12:25 am to 2:55 am EDT.

Neptune is positioned between Jupiter and Saturn nowadays. This month, the distant planet’s faint, blue speck will be positioned a generous fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s upper right, and two finger widths to the upper right (or 2.3° to the celestial west-southwest) of a small star named 20 Piscium. On Friday, the blue planet will reach opposition. At that time Neptune will be closest to Earth for this year – a distance of 4.32 billion km, 4 light-hours, or 28.91 Astronomical Units. Blue Neptune will shine with a slightly brighter magnitude 7.8. Since it’s directly opposite the sun in the sky, Neptune will be visible all night long in backyard telescopes. Good binoculars will show it, too, if your sky is very dark. Your best views will come after 9 pm local time, when the blue planet has risen higher. Around opposition, Neptune’s apparent disk size will peak at 2.4 arc-seconds and its large moon Triton will be the most visible.

The medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon around 11 pm local time and will deliver nice views in a backyard telescope after about 1 am local time. In a telescope, Mars will show a small, 86%-illuminated disk. Watch for the bright reddish star Aldebaran positioned several finger widths to Mars’ lower right (celestial south). Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. We’re 134 million km (or 7.45 light-minutes) from it this week.

Uranus is within reach of binoculars, except when the bright moon will be right next door to it on Tuesday and Wednesday. The blue-green speck of the planet is located a generous fist’s width to the upper right (or 12° to the celestial southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Ram. The magnitude 5.7 planet will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by midnight local time this week.

Diving into Delphinus

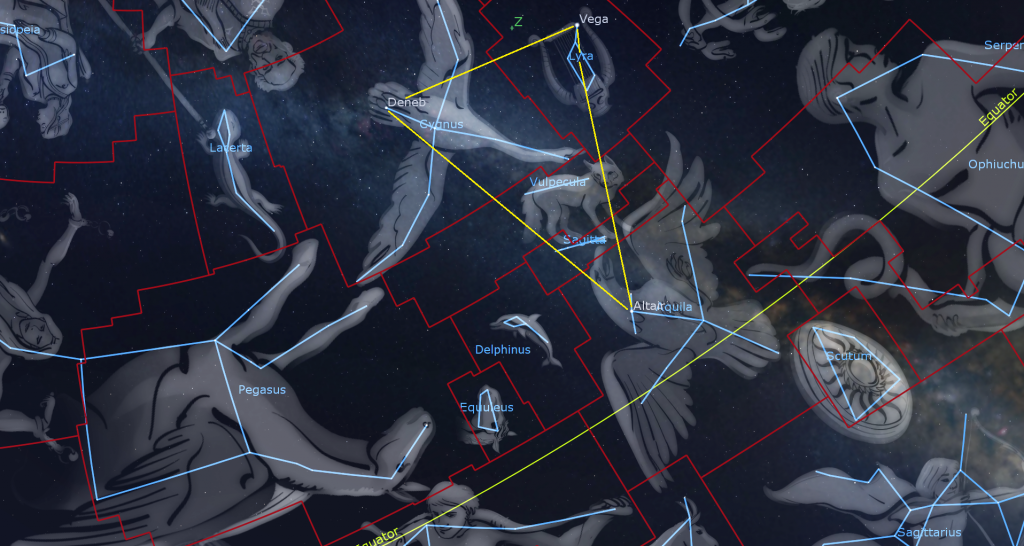

Sitting just to the lower left of the Summer Triangle asterism on September evenings is a cute little constellation named Delphinus (the Dolphin). If you look southeast after dusk, the dolphin will be found swimming a little more than halfway up the sky, directly below the bright star Vega and bracketed by Deneb to its upper left and Altair to its right. The stars of great Pegasus border it to the left (celestial east). Delphinus is ranked 69th in area among the 88 constellation. The even smaller constellations of Sagitta (the Arrow) and Equuleus (the Little Horse) are located above and below the dolphin, respectively. Only Crux is smaller than those two.

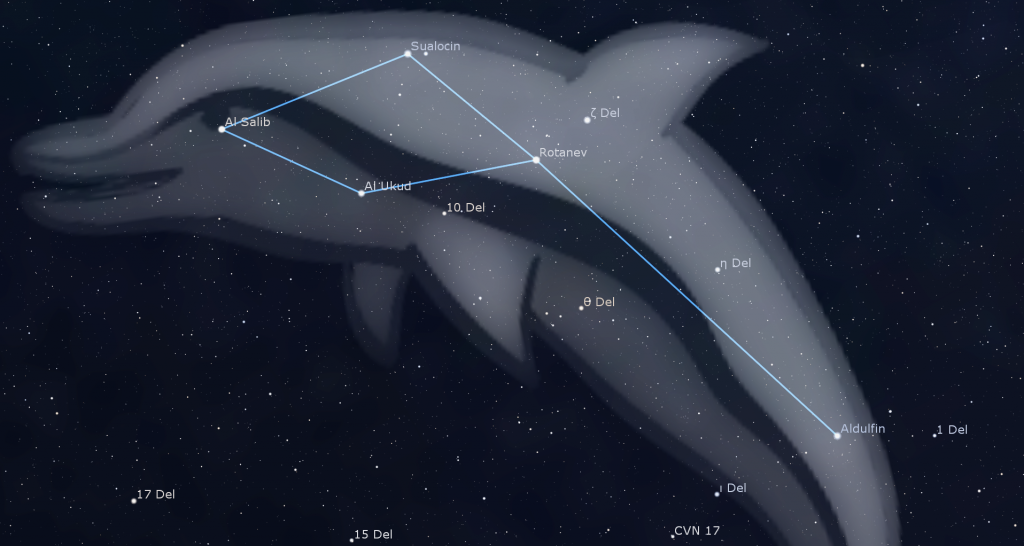

Delphinus consists of a small elongated diamond of four medium-bright stars (two finger widths across and one finger width tall) forming the head and body. The dolphin’s tail is composed of modest stars extending about three finger widths to the lower right (or celestial south) of the diamond. The creature’s five main stars can be seen with unaided eyes in a reasonably dark sky, and will all fit within most binoculars’ field of view. The little diamond of stars is also known as the asterism Job’s Coffin.

Delphinus’ location just 10° north of the celestial equator has allowed it to be enjoyed worldwide. One Greek legend tells the tale (pardon the pun) of Poseidon, god of the seas, being assisted in a matter of the heart by a friendly dolphin, and rewarding it with a place of honour in the heavens. In another story, a dolphin carried the famous 7th Century musician and poet Arion of Lesbos home to Greece after he jumped overboard to avoid being robbed and murdered by sailors on a voyage home. Apollo placed the heroic mammal in the sky next to Arion’s lyre, the constellation Lyra. Chinese astronomy sees the stars of Delphinus as a pair of gourds, and the Koreans a fruit. South American tribes saw an armadillo, while the south Pacific islanders saw the fish. To me, he could also be a Kiwi’s head!

Delphinus’ brightest two stars are bluish-white Sualocin, where the blowhole would be, and whitish Rotanev, at the nape of the neck. Those funny names are actually the name of 19th century astronomer Nicolaus Venator spelled backwards. He participated in creation of a star catalogue, and inserted the two modest stars, for fun! Sualocin and Rotanev are 240 and 97 light-years away, respectively.

A backyard telescope will show that Sualocin is actually a matched pair of white, close-together double stars. Rotanev, too, is a close double, but with contrasting brightness and colour. It’s a binary system where the two stars orbit one another once every 27 years. A fainter star named Zeta Delphinus that shines half a degree above Rotanev marks the dolphin’s fin. The star at the dolphin’s nose, named Al Salib or Gamma Delphinus, is a somewhat wider-apart double star with one component a greenish colour. Look just below it for another easily split of stars named Struve 2725.

Use binoculars to seek out the whitish, magnitude 5.35 star named Eta Delphinus sitting halfway between Rotanev and the white tail star Aldulphin, a name meaning “tail of the dolphin”. The star at the bottom corner of the diamond, marking the dolphin’s tummy, is a pulsating variable star named Al Ukud or Delta Delphinus. It has an orange tint, as do the two fainter stars named 10 Del and Theta Del which are along a line between it and Aldulphin.

Delphinus lies near the Milky Way, so there are rich fields of stars to be seen throughout it. Scan around with your binoculars or telescope! The only prominent deep sky objects are two globular star clusters designated NGC 7006 and NGC 6934. They are also members of Sir Patrick Moore’s best of the sky Caldwell List, as numbers C42 and C47, respectively. Globular clusters are dense balls of stars that orbit the Milky Way galaxy, like bees around your lemonade. These two are not very bright, and need an 4” aperture telescope, or larger, to readily see them. At 135,000 light-years away, C42 is one of the most remote of our galaxy’s globulars.

Delphinus hosts several planetary nebulae, the glowing shells of gas left behind when stars similar to our sun reached the end of their lives. The Blue Flash Nebula (or NGC 6905) is located by extending a line from Al Akud to Sualocin by a palm’s width. In a good telescope it resembles a little blue egg.

Aurorae Alert!

If you missed last week’s information about the aurora borealis, which have been more frequent recently, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, September 13 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll learn about variable stars! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Tuesday, September 13 from 7 to 8 pm EDT, University of Toronto Mississauga will stream a free public presentation by Professor John Percy entitled Misconceptions about the Universe: From Everyday Life to the Big Bang. Details and the Eventbrite link are here.

RASC’s Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Friday night, September 16 from 8 to 9:30 pm EDT, tune into the online DDO Up in the Sky. There will be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday September 14, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!