Moonless Evenings Launch Lunar New Year while Jupiter and Venus Bookend the Night!

The beautiful Rosette Nebula in Monoceros consists of a circular patch of glowing hydrogen gas and an internal star cluster, created as the hydrogen gas collapsed. Stan Noble tool this image, which was featured as the SkyNews picture of the week for November 3, 2017, in Aneroid, Saskatchewan. The image spans about two finger widths of sky, left-to-right. More of Stan’s beautiful images can be enjoyed at https://www.astrobin.com/users/stannoble/

Happy Lunar New Year, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 4th, 2024 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

This week’s new moon will initiate the lunisolar new year. The moonless nights will be ideal for sweeping the sky treasures in the winter constellations. Meanwhile Jupiter will hold court in evening and Venus will align with Mars and Mercury in morning. Read on for your Skylights!

Lunar New Year and Lunisolar Calendars

“Xīn Nián Kuài Lè!” 新年快乐! It’s Lunar New Year for many Asian countries, including China, Korea, and Vietnam! I touched upon the topic last week. Let’s dive a little deeper.

Unlike the Gregorian calendar used by Western Hemisphere societies, a lunisolar calendar uses the 29.53-day cycle of the moon’s phases to define the months of the year – usually starting each month when the new moon phase occurs, or on the day when the young crescent moon is first glimpsed after sunset. The placement of those months is anchored to one of the solstice or equinox events. Since solstices and equinoxes are Earth-Sun phenomena, and are completely independent of the moon’s phases, lunisolar calendars drift compared to our Gregorian system. And, because the moon runs through its cycle of phases 12.37 times per year, every second or third lunisolar year requires an extra 13th intercalary or “leap” month.

Several world cultures (e.g., Hindu, Hebrew) still follow a lunisolar calendar, while Muslims follow a purely lunar calendar. The Chinese lunisolar calendar places the December solstice into the eleventh month – causing the first month of the subsequent year to begin about two months later – on the new moon that occurs somewhere between January 21 and February 20 on our calendar. Most of the time, that moon phase lands in early February.

When the moon officially reaches its new moon phase on Friday, February 9, 2024 at 5:59 pm EST, 2:59 pm PST, or 22:59 Greenwich Mean Time, it will give rise to the Lunar New Year observed in many Asian countries. Since that new moon will happen on Saturday morning, Beijing-time – that will be the first day of Chinese New Year holiday celebrations worldwide. It is also the first day of the Spring Festival 春节, or Chūn Jié (“CHWUN-jee-EH”), which ends with the Lantern Festival on the full moon two weeks later. Asian families will kick things off early by celebrating New Year’s Eve, Friday night, with a meal together. The Vietnamese new year is called Tết, short for tết nguyên đán, meaning “Festival of the First Morning of the First Day”. Koreans celebrate Seolla, from Eumnyeok Seollal “lunar new year”. Japan adopted the Gregorian new year reckoning of January 1 in 1873.

Happy Year of the Dragon! The Chinese use a zodiac system – but their version doesn’t relate to the sun’s journey along the ecliptic, or even to any of the animal constellations. Instead, their zodiac preserves the sense of that word from the Ancient Greek expression zōdiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακός κύκλος), “cycle of small animals”. They assign an animal and its attributes to each year in a repeating 12-year cycle. That interval may have arisen from the 11.85-year orbital period of Jupiter!

By the way, among the modern system of 88 official constellations, 42 represent animals – from Apus (The Bird of Paradise) to Vulpecula (The Fox). I delight in displaying the drawings for all the constellations in my portable planetarium and challenge the visitors to find the animals. Of the remaining 46 constellations, 28 are objects (tools, musical and scientific instruments, ships, weapons, etc.), fourteen are human figures, two are chimeras, namely Centaurus (the Centaur) and Sagittarius (the Archer), and two are natural features, including Eridanus (the River) and Mensa (the Table Mountain). This website lists them.

The order of the animals in the Chinese zodiac is said to have been determined by a great race to become the guards of the Jade Emperor – with their rank determined by the order in which the animals arrived at the finish line – the palace gates. The race involved both running and swimming. The mighty ox was a shoe-in to win the race. But the rat woke up early on race-day and took the lead. Arriving at the river, he feared to cross it. When the ox arrived, the rat jumped onto the gentle ox’s back and hitched a ride across. Upon reaching the opposite shore, the little rascal jumped off of the tired ox and raced ahead to win the race, leaving the ox with second place! Did he cheat – or was he clever, and worthy to be senior-most among the guards? In another variation of the story, the cat and the rat, who had always been best friends, rode the ox across together – but the rat pushed the cat into the water and ran on to win. They’ve been bitter enemies ever since.

The fast and competitive tiger and rabbit were the next to arrive. The tiger’s greater size gave him an advantage over the small rabbit, which had to cross the river by hopping on stones and a log. The winged dragon, a shoe-in to win, stopped to do several acts of kindness, including helping to push the stranded rabbit’s log to shore. 2024 is the fifth year of the current cycle, named for the fifth-place finisher, the dragon. When asked their age, Chinese people will commonly answer with the animal of the year they were born in, requiring you to guess which group of the twelve years they were born in.

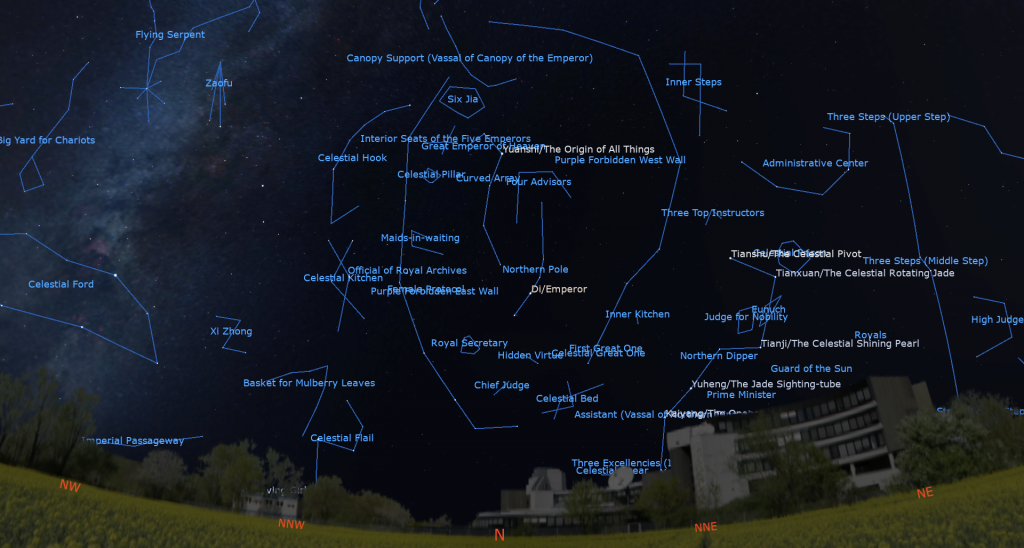

Speaking of the emperor, in traditional Chinese astronomy, the Jade Emperor’s Palace or “Purple Forbidden Enclosure” was represented by the stars of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), including the pole star, Polaris. That’s where the spirit of the emperor went after he died. Surrounding that part of the sky were constellations representing the eastern and western walls of the palace, which used parts of Draco (the Dragon), kitchen, guest house, archive, advisors, maids-in-waiting, and more.

The Chinese celebrate the New Year with red decorations and firecrackers because, stories say, long ago a mythical beast called Nian was terrorizing rural villages. After many years, an old man declared he would deal with Nian while the rest of the villagers hid during the night. He scared the beast away by hanging red paper around the village and making loud noises. Henceforth, when New Year was approaching, people would wear red clothes, hang up red lanterns, place red scrolls on windows and doors, and use firecrackers to frighten away the Nian. It never bothered the village again. The Chinese word for year is “nián” which is pronounced “knee-EN” and written as 年.

The Nisga’a indigenous group of British Columbia traditionally celebrate their new year when the crescent moon first appears after its new phase in February or March. Their celebration is called Hobiyee, a name derived from the expression “Hobixis Hee!”, which means “the moon is in the shape of the hoobix”, the bowl of the Nisga’a traditional wooden spoon. The young moon’s orientation after sunset, with its horn-tips pointing upwards, resembles a celestial scoop – ready to be filled with an abundance of salmon, river saak (candlefish), berries, and more. Children gleefully run about with their arms curved upwards, pretending to be the moon. The first month of the Nisga’a year is called Buxw-laks, where buxw means “to blow about” and laḵs means “needles” – a sure sign of winter’s end.

The Moon

The moon will be missing from the evening sky worldwide until after it has passed the sun and re-entered the evening sky on Saturday. In the meantime, you can see the old crescent moon sharing the southeastern sky with Venus before sunrise on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday morning.

Monday morning’s moon will shine to the left (or celestial east) of Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius (the Scorpion). But the moon will actually be sliding through the territory of next-door Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Venus will gleam off to their left.

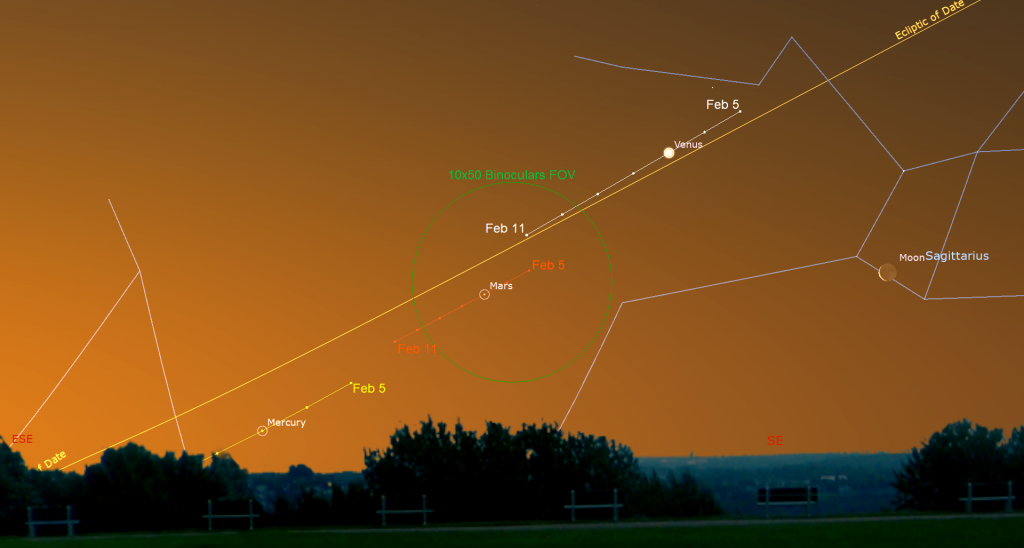

On Tuesday morning the moon’s daily shift eastward by 13° will carry it into Sagittarius (the Archer), where it will share the southeastern predawn sky with the bright planet Venus and far fainter Mars. Skywatchers viewing the scene before about 6 am local time can spot the 16%-illuminated crescent moon shining about two fist diameters to the right (or 18 degrees to the celestial WSW) of Venus, with the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) sprinkled between them. Take a photo! Once Mars rises shortly after 6 am it will be located a palm’s width to the lower left of Venus. Observers viewing from the tropics may also be able to spot Mercury to the lower left of Mars.

On Wednesday morning, the even thinner crescent moon will hop east to shine at Venus’ lower right, setting up a second photo opportunity. The moon will still be quite far from the sun on Thursday morning, but the shallow slope its orbit makes with the horizon will cause it to rise just minutes before the sun, thereby hiding it in the bright sky.

As I mentioned above, the moon will officially pass the sun at new moon phase on Friday afternoon in the Americas. At that time it will be located in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), approximately 4.6 degrees south of the sun. While new, the moon is traversing the space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only shine on the far side of a new moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, our natural satellite becomes completely hidden from view for about a day – unless a solar eclipse occurs! This new moon will arrive only 20 hours before the moon’s closest approach to Earth this month (or perigee). The combined pull of the sun and moon will generate large tides worldwide.

For about an hour after sunset on Saturday, the very delicate crescent of the young moon will appear just a few finger widths below (3.5 degrees to the celestial SSW) of Saturn’s yellowish dot. Their conjunction above the southwestern horizon will be tight enough for them to share the view in binoculars, but be sure to wait for the sun to completely disappear before turning any optical aids towards them.

The moon will be easier to see next Sunday when its 5.7%-illuminated crescent will linger over the west-southwestern horizon after sunset.

The Planets

We’re in the final days of our time with Saturn after about six months of fine views. This week you can seek out Saturn’s dot positioned just above the west-southwestern horizon after dusk. With each passing day, Earth’s motion around the sun will cause Saturn to shift sunward and drop lower in the sky.

The faint and tiny bluish speck of magnitude 7.9 Neptune will follow Saturn down by 9 pm local time – but you can view the planet in good binoculars or a backyard telescope around 7 pm. After that it will be too low for good views of it. Search for the planet halfway between the medium-bright stars Deneb Kaitos Shemali (or Iota Ceti) and Gamma Piscium. Those stars are about two fist diameters apart, so split the difference.

Jupiter will continue to be the main event when it comes to evening planets. Its brilliant dot will emerge high in the south-southwestern sky after dusk, with the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) to its upper right. It won’t set until after midnight, but the best telescope-viewing time will be as soon as you can see it. Bright planets can show more detail in a twilight sky. Jupiter will look great under magnification until about 10:30 pm local time.

Any decent pair of binoculars can show you Jupiter’s four largest Galilean moons lined up on both sides of the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. In the Americas, the moons will flank Jupiter in pairs tonight (Sunday) and all gather to Jupiter’s west on Monday.

Any small telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, is visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Wednesday and Friday. It’ll appear late tonight (Sunday), on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday night. The spot has been rather a pale pink in colour for some time now. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. For those in the Americas, Europa’s shadow will cross Jupiter on Wednesday, February 7 from 7:20 to 9:35 pm EST (or 00:20 to 02:35 GMT on Thursday). Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern polar region on Sunday, February 11 from 5:33 to 7:05 pm EST (or 17:33 to 00:05 GMT). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Blue-green Uranus, which is also in Aries (the Ram), is an hour behind Jupiter on the ecliptic. This week it will set around 1:30 am local time. The magnitude 5.7 planet is quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes in this week’s dark, moonless skies. Uranus will be positioned 1.1 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper left (or 11° to its celestial ENE). The bright Pleiades star cluster will sparkle a generous fist’s width above Uranus (or 12° to its celestial northeast). As another guide, the three bright stars of Orion’s Belt are aimed at Uranus.

The rest of the planets will be strung out above the southeastern sky before sunrise. Extremely bright Venus will rise at about 6 am local time. The planet is rapidly swinging toward the sun, shortening its viewing time with each passing day. This week Venus will shift east through eastern Sagittarius (the Archer) by more than an outstretched palm’s width. Venus will be a gleaming point of light until sunrise. A telescope or strong binoculars will reveal that Venus has an almost round shape.

Much fainter Mars and Mercury will be to Venus’ lower left (or celestial east). On Monday morning, Mercury will appear 1.5 fist diameters from Venus. Mars will be midway between them. Observers viewing from near the tropics will more easily see Venus, Mercury, and Mars. Mars will drop sunward each morning, so it we will lose sight of it by midweek. Mars and Venus will move toward one another.

Don’t forget that the old crescent moon will shine near Venus on Wednesday morning, and between Mercury and Mars on Thursday morning.

Eyeing Orion

If you missed last week’s tour of the eye-catching constellation of Orion (the Hunter) and his famous three-starred belt, I posted it with sky charts and photos of some of the objects here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, February 7 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, Observing and Imaging Sunspots and Solar Storms, and How Ancients Predicted Eclipses. Details are here.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!