Moonless Midnights, Morning Planets in Line, and Boötes Beauties!

This image of spiral galaxy NGC 5248 (also known as Caldwell 45) in southwestern Boötes was captured by Adam Block’s team at Mount Lemmon SkyCenter, University of Arizona on March 3-4, 2011. The image spans 16 arc-minutes of sky, measuring left-to-right, or half the moon’s diameter.

Hello, Spring Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of May 22nd, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

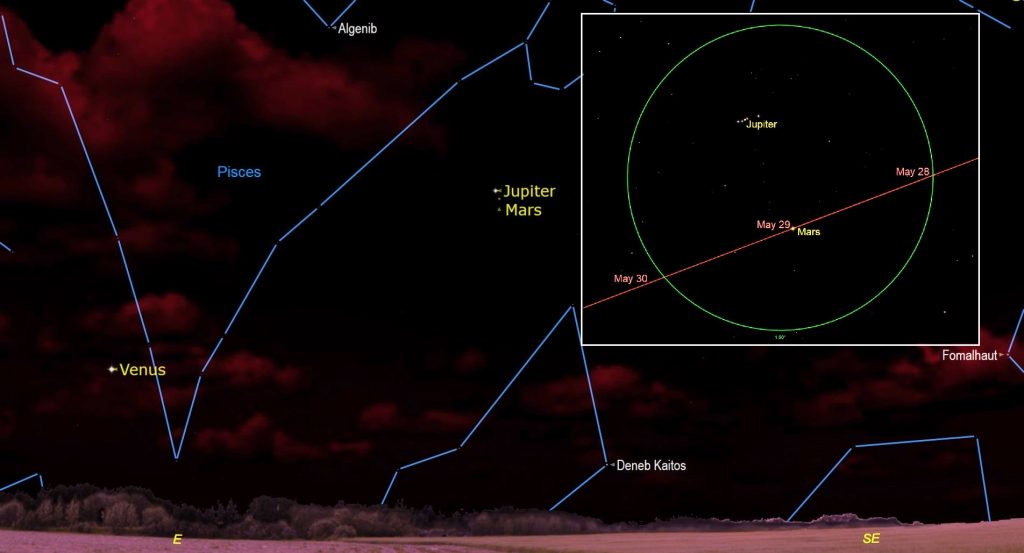

This week, the moon will only shine in the east before sunrise, leaving night skies worldwide dark for last looks at spring galaxies and the delights of Boötes. The waning crescent moon will travel below the bright planets in the eastern pre-dawn sky, where Mars and Jupiter will dance telescope-close! Read on for your Skylights!

Possible Meteor Storm Warning!

Here’s a heads-up about a possible brief meteor storm (i.e., far more per hour than is usual) just after midnight Eastern time on Monday night, May 30-31. More about that next week!

The Moon

This is the final week of the lunar month. The moon will only appear the predawn sky, rising in the hours before sunrise while it slides closer to the sun every morning. That means that stargazers worldwide will enjoy delightfully dark skies from the end of astronomical twilight until well beyond midnight. Astronomical twilight is defined as the time while the sun is between 12° and 18° below the horizon, both in evening and in morning. When the sun is more than 18° below the horizon, a clear, moonless sky is as dark as it can get. During civil twilight, the sun has just set and the sky is still rather bright. Nautical twilight is the medium-dark sky falling between the other two types. We’re only weeks away from the June equinox, the shortest night of the year. At the latitude of Toronto this week, the sky will only be truly dark between about 11 pm and 3:30 am local time, but you can observe brighter targets starting around 10 pm.

The moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 2:43 pm EDT or 18:43 Greenwich Mean Time today (Sunday) – but it won’t be above the horizon for observers in the Americas because lunar phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation. At third (or last) quarter the moon appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. On Monday morning, the then waning crescent moon will rise among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) at about 3 am local time. Early risers can look east-southeast for the creamy dot of Saturn shining to the moon’s upper right (celestial west) and the duo of Jupiter and Mars to the moon’s lower left (celestial northeast).

On Tuesday morning, the moon will shift into eastern Aquarius and closer to Mars-Jupiter, making a nice widefield photo opportunity. Wednesday morning will find the pretty crescent moon just a few finger widths below Jupiter, with the bright planet Venus down to their lower left (celestial east) – another pretty picture opportunity in the minutes after about 4:30 am! If Wednesday morning is cloudy, the moon will sit between Venus and Jupiter-Mars on Thursday – although it’ll be rather low in the eastern sky. The very slim crescent of the old moon will shine in a brightening sky to Venus’ lower left on both Friday and Saturday morning – our last glimpses until it returns as a young crescent shining after sunset next week.

The Planets

Mercury swept past the sun during inferior conjunction on Saturday. Mercury can pass the sun on Earth’s side of the solar system, an event known as inferior conjunction, or it can pass it on the far side of the sun, known as superior conjunction. Only Mercury and Venus can experience both types of conjunction. None of the other planets can experience inferior conjunction.

This week Mercury will enter the morning sky to join the rest of the planets. Its position well below (celestial south of) a slanted morning ecliptic will prevent observers at mid-northern latitudes from seeing the speedy planet until it swings farther from the sun next week – but anyone viewing from the tropics and farther south will spot the planet by week’s end. They can see the moon pass only a few finger widths to the left of Mercury next Sunday morning.

Mercury’s arrival will set up a unique show of five bright planets shining in the eastern pre-dawn sky, arranged in order of their distance from the sun during all of June! But that won’t happen until Mars and Jupiter trade places on Sunday morning, May 29. On that date, the faster motion of Mars will carry it past much brighter Jupiter in a very tight planetary conjunction. Both planets will share the view in a backyard telescope from Friday to next Tuesday, with Mars approaching from Jupiter’s right (celestial west). At closest approach on Sunday morning, Mars will sit 0.6 degrees (a little more than the moon’s diameter) below Jupiter, although your telescope may flip and/or mirror-image their arrangement. The optimal viewing time will be 4 to 5 am local time.

Once Mars has moved to Jupiter’s left the planets will be in order. Until then, we can still enjoy the show. The small yellow dot of Saturn will appear above the treetops towards the east-southeast by about 3 am local time. Almost 90 minutes later, Mars’ little reddish dot and much brighter, whiter Jupiter will appear about three fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 35° to the celestial east). By 5 am local time, the brightest planet, Venus, will round out the lengthy chain of planets. Fainter Saturn and Mars will disappear into the brightening sky towards sunrise. As I mentioned above, the waning crescent moon will pass below the string of planets on the weekday mornings.

But there’s more than meets the eye! The main belt asteroid named (4) Vesta will be traveling a slim palm’s width below and to the lower left (or 5° to the celestial southeast) of Saturn – but you’ll need good binoculars or a backyard telescope to see its magnitude 7.1 speck. Faint, blue Neptune will be lurking a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s upper right (celestial west). Uranus will rise around 5 am local time. Its magnitude 5.9 blue-green speck will become visible in the pre-dawn sky after it passes close to Venus on June 11.

Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s full globe extending above and below its rings, and a few of its moons. Venus will exhibit a football-shape in a telescope or in good binoculars. Mars will shine with a tiny, 88%-illuminated disk. Flanked by its four Galilean moons, Jupiter’s much larger orb will sport dark equatorial bands, the Great Red Spot on Thursday and Saturday morning, and the small back shadow of Ganymede’s disk on next Sunday morning. Turn all optics away from the east before sunrise, please!

Peering at the Ploughman

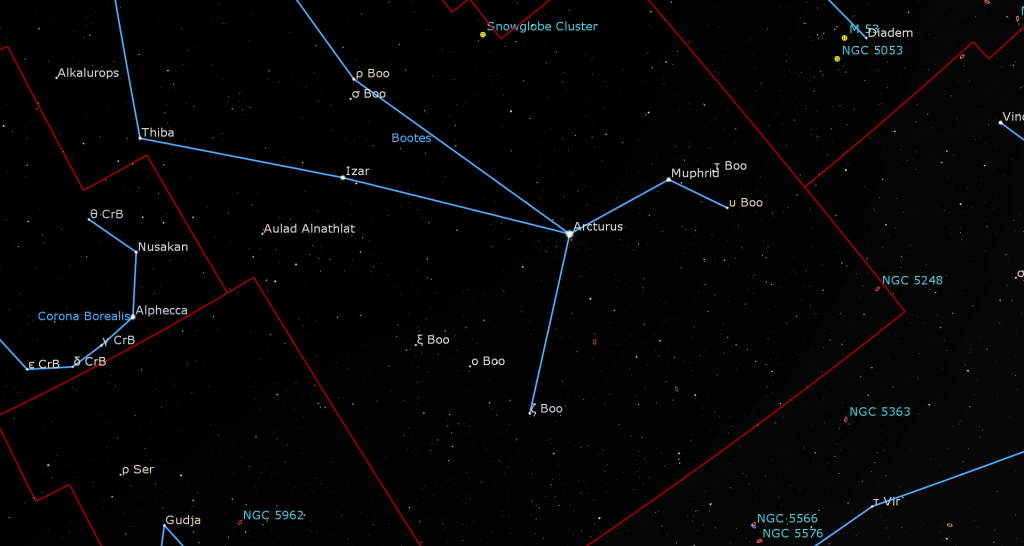

The absent moon during evening for the next two weeks, and the lovely late spring nights, offer a fine opportunity to explore the realm of Boötes (“Bow-OH-tees”), the Herdsman or Ploughman.

After dark, face southeast and look two-thirds of the way up the sky for the very bright, orange-tinted star Arcturus (or Alpha Boötis). The fourth brightest star in the entire night sky, and a “neighbour” of our sun at a mere 37 light-years away, Arcturus means “Guardian of the Bear” in Greek, because it always rises after Ursa Major (the Big Bear), which sits above it (celestial west) this month. Arcturus shines with that colour because it is just passing middle-age for a star, starting on its way towards the red supergiant stage.

The entire constellation is visible from everywhere on Earth, but Antarctica. In Chinese, Arcturus is known as Dà Jiǎo Xīng 大角星, “Great Horn Star”, part of the huge Azure Dragon of the East asterism, which stretches from Boötes and Virgo on the west to Scorpius and Sagittarius on the east. The star Antares marks the dragon’s heart.

Arcturus anchors the bottom tip of a large, kite-shaped asterism within the larger constellation of Boötes. The rest of the stars in the kite are bright enough to be visible under somewhat light-polluted skies. The kite measures 2.3 fist diameters on the long axis and a fist’s width across at its widest point. Boötes stands upright above the ecliptic, above Virgo (the Maiden) and below the sinuous dragon, Draco. He is bordered on his left (celestial east) by Hercules and Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown) and by Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair) and Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs) on the right (celestial west).

In May-June, Ursa Major and its Big Dipper is located above Boötes. In late summer the dipper drops to his right. Even when Boötes’ stars shine before dawn, he still follows the dipper’s handle stars across the sky. It’s likely that the Ploughman moniker refers to the Big Dipper’s other name, the Plough.

Let’s tour Boötes’ stars. A widely separated pair of medium-bright stars shine a fist’s diameter to Arcturus’ upper left (celestial NNE). The lower, brighter one is Izar (ε Boötis), meaning “Loin Cloth”. (The word Boötis is Latin for “belonging to Boötes”. We’ll use “Boo” to shorten things.) The name Izar resembles Mizar, the star at the bend in the Big Dipper’s handle. That star also serves as a loin – of the bear.

A faint star named 34 Boo sits just half a finger’s width below Izar. In a telescope, Izar itself splits into a gorgeous double star – with one partner golden and the other star white, or greenish, and huddled very close to it. Those two companions are orbiting one another in a true binary star system some 200 light-years from our sun. A few finger widths to the upper right of Izar, on the upper (western) side of the kite, we find a medium-bright star designated Rho Boötis (ρ Boo). This star marks the herdsman’s western hip. See if you can see a small star close to Rho, on the Izar side. That’s Sigma Boötis (σ Boo), a sunlike star 50 light-years away from us.

Traveling about twice as far from Arcturus, along the line drawn through Izar, brings us to the herdsman’s eastern shoulder, a medium-bright star designated Delta Boötis (δ Boo) or Thiba. Thiba is a yellowish G8-class, sun-like star about ten times more massive than our sun. It is located 117 light-years away from our solar system.

A star named Nekkar “Ox Driver” shines a generous palm’s width above (or 7.5° to the celestial northwest) of Thiba. Nekkar (or β Boo) marks the herdsman’s head and the top of the kite. Nekkar was originally a blue star. It’s now aging through a phase that is causing it to temporarily resemble a large version of our sun – on its way to becoming a brighter, red giant star.

A medium-bright, triple star named Alkalurops (or Mu Boo), a name derived from “Shepherd’s Staff”, sits about four finger widths to the upper left (or 4.5° to the celestial northeast) of Thiba. It forms a squat triangle with Thiba and Nekkar. Two of Alkalurops’ stars can be discerned with sharp eyes or binoculars, and one of them splits into two stars when viewed through a telescope. All three stars are orbiting one another in a dance that takes at least 125,000 years for one orbit. Before moving on, position Alkalurops towards the right side of your binoculars’ field of view and look on the left for two close together stars named v1 and v2 Boo. The have dramatically different colours!

Above and between Nekkar and Rho Boo shines a medium-bright star named Seginus (or γ Boo), which marks the herdsman’s western shoulder. Seginus is a white giant star that is evolving towards becoming a red giant one day. This 85 light-years distant star is spinning about 70 times faster than our sun!

The medium-bright stars positioned to the lower right (celestial south) of Arcturus form the herdsman’s legs and feet. The left (eastern) foot, which sits less than a fist’s diameter below Arcturus, is designated Zeta Boötis (ζ Boo). In a telescope at high power it is revealed to be a nice, matched pair of close-together white stars. The star shining two finger widths to the upper left (northeast) of Zeta is Pi Boo, another nice double star. Double that distance to the fainter double star Xi Boo (ξ Boo).

Moving about four finger widths to the right from Arcturus, along Boötes’ western leg, brings us to the bright star Muphrid (η Boo), meaning “the Solitary star of the Lancer”. Murphrid too, has a composition similar to our sun. Even though it is actually the same distance away from us as Arcturus, its inherent brightness is lower, so it appears much dimmer in the sky. Dropping down slightly and moving farther to the right brings us to Upsilon Boötis (υ Boo), a very distant red giant star.

All the stars within our galaxy are in motion, jostling about as they orbit the galactic centre every quarter of a billion years or so. Some stars move faster, or are located closer to us – so they exhibit a greater apparent motion compared with the surrounding stars. Astronomers call this phenomenon proper motion. That’s why star charts need to be updated about every ten years. Arcturus has a very high proper motion southward. In a few thousand years, the herdsman’s legs will be bent upwards with Arcturus below his knees!

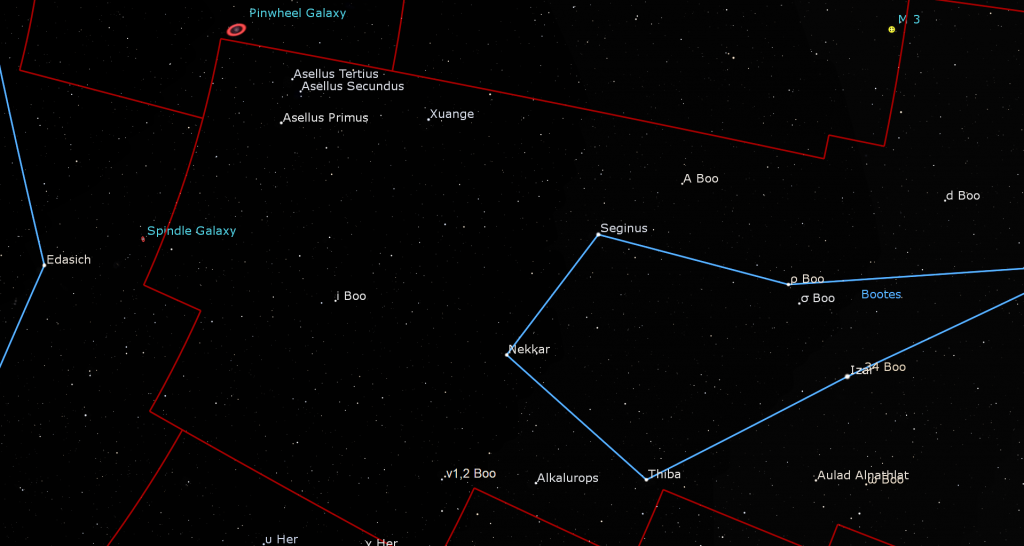

Boötes’ territory extends almost to the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle. A palm’s width below the bright star Alkaid at the tip of the handle, look for a tight grouping of three stars that represent the herdsman’s upraised hand. Their names are Asellus Primus, Asellus Secundus, and Asellus Tertius “First, Second, and Third Donkey” (and Theta, Iota, and Kappa Boo). The two higher (westerly) donkeys are telescopic double stars. The area around all three is a lovely, rich field for viewing because it’s full of small galaxies. The famous and easy-to-see Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 101) is located only a few finger widths to the left (celestial north) from them!

Positioned well off the Milky Way, Boötes hosts few bright deep sky objects. A palm’s width to the right (or 6 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Rho Boötis sits the globular star cluster known as the Snowglobe Cluster (and NGC 5466). It will appear as a small, fuzzy patch in binoculars and backyard telescopes under a dark sky. A further palm’s width to the upper right (or 5° to the celestial west) of the snowglobe, in next-door Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs), is the magnificent and much brighter globular cluster named Messier 3 – an easy city object. The constellation does host a great many distant galaxies. One worth checking out is the terrific, magnitude 11 spiral galaxy NGC 5248, also known as Caldwell 45. It’s located in the southwestern corner of the constellation. Take the line drawn from Murphrid to u Boo and quadruple it.

Use your binoculars to seek out a short chain of 6 and 7 magnitude stars located below and between the herdsman’s feet – the kite’s string!

Globular Clusters

Moonless nights are terrific for seeing globular star clusters, many of which can still be spotted in suburban skies. During May and June, the best ones observable from mid-northern latitudes become well-placed in the eastern evening sky. Last week, I posted finder charts for many of them here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, May 24 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll discuss how to prepare for an evening of stargazing – cloud forecasts, equipment preparation, target selection, etc. Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program and share some galaxy-viewing tips. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Friday evening, May 27 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Mississauga Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Dr. Samantha Lawler, assistant professor of astronomy at Campion College at the University of Regina. Her talk is titled Megaconstellations of Satellites are about to Ruin the Night Sky for Everyone. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on Zoom here. Details are here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!