Morning Mercury, Evening Venus Leaves Antares, Orionids Meteors at Max, and Jupiter Sports Spots!

This spectacular long exposure composite combines twenty photographs of the Orionids Meteor Shower taken on October 21, 2006 near Bursa, Turkey by Tunc Tezel. It was NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day for October 23, 2206. Orion, with his distinctive belt, shines at top centre. The shower’s radiant is at top left.

Happy, mid-October, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 17th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a copy!

The bright Hunter’s moon will flood the world’s night skies with light this week, somewhat spoiling the Wednesday/Thursday peak of the annual Orionids meteor shower. Every evening, Venus will set early, leaving the gas giant planets to shine until after midnight. Jupiter will host several shadow transit events, Mercury will return to visibility in the eastern pre-dawn sky, and the Great Bear will descend into her den. Read on for your Skylights!

Orionids Meteor Shower

We’ve finally entered meteor shower season! Over the next few months, Earth will experience several showers. My friend Blake Nancarrow created a very informative graph of meteor shower intensity throughout the year here, on his Lumpy Darkness blog.

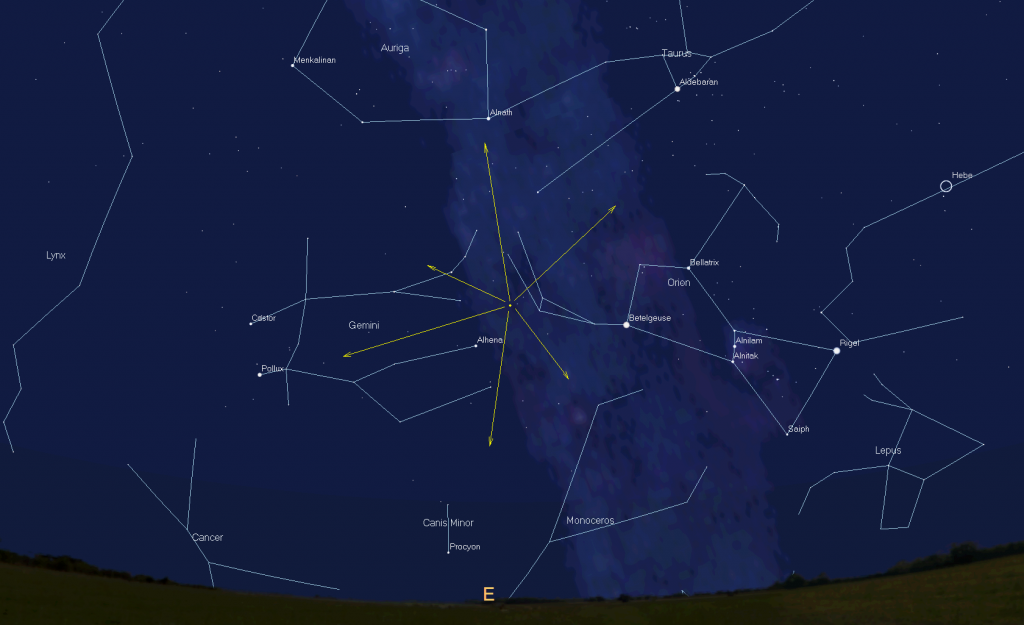

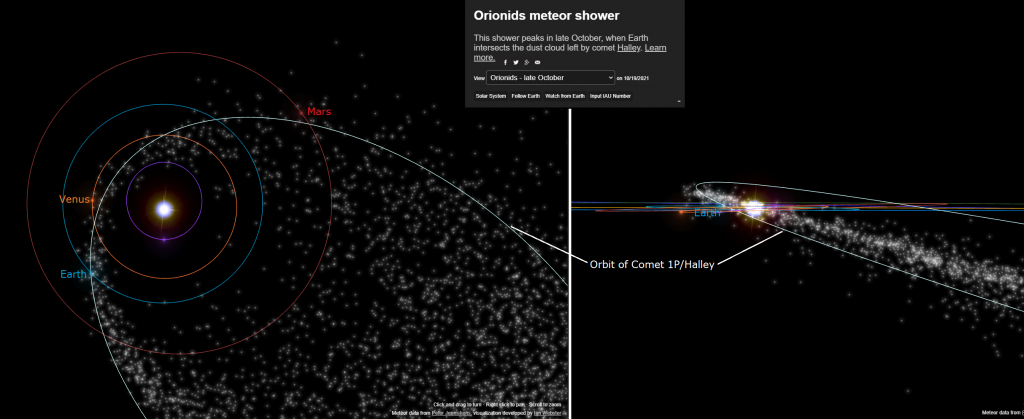

The excellent Orionids Meteor Shower, which is observable world-wide, happens every year between September 23 and November 27. That’s when Earth is plowing through a cloud of fine particles dropped by repeated past passages of the periodic comet designated 1P/Halley, or Halley’s Comet. The Orionids (for short) will peak in the hours before dawn (in your local time zone) on Thursday, October 21. At that time, the sky overhead will be pointing toward the densest region of the particle field, generating as many as 10-20 meteors per hour.

Even though the most meteors will be seen before dawn, you will still see a reduced number of them during Wednesday evening and beyond midnight, and on the surrounding nights. The meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but true Orionids will seem to be travelling in a direction away from a location in the sky (called the radiant) that is near the bright red star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion – giving this shower its name. The radiant will rise at about 10:30 pm this week – but up to half of the Orionids will be travelling downwards, and will therefore be blocked by your local horizon, until Orion climbs higher.

Although not particularly numerous, Orionids are known for being bright and fast-moving. Unfortunately, the moon will be shining brightly all night long, somewhat spoiling Orionids meteor-watching for this year. Next year’s shower will be much better.

While the Orionids Shower will last until late November, the meteors will decrease in quantity every night after Thursday’s peak. The Orionids has a broad period of activity because the orbit of Halley’s Comet is tilted by only 17° from the plane of the Solar System, and it also crosses Earth’s orbit obliquely. There’s a terrific, interactive, 3D meteor shower visualizing tool at https://www.meteorshowers.org/.

As a general rule, to see the most meteors, get away from light-polluted urban skies and find a dark site with plenty of open sky. If the moon is up, try to hide it behind a tree or building. You won’t see meteors if it’s cloudy. Don’t bother using binoculars or a telescope for meteors – their fields of view are too narrow. And don’t watch the sky near the radiant because those meteors will be travelling towards you and will produce very short streaks. Just keep your eyes on the sky overhead.

To preserve your eyes’ dark adaptation, avoid the bright white light from phones or tablets. Red light is fine – so cover the screen with red film or use red mode. If the peak night forecast calls for clouds, try the nights before or the nights after. Good luck!

The Big Bear Hibernates

In early October every year, the Big Dipper asterism, which is circumpolar for observers located north of 35 degrees North latitude, reaches its lowest position above the northern horizon in late evening – as if it is scooping up a bowl of cold, refreshing northern water! North American indigenous traditions tell the tale of the Great Bear (Ursa Major) heading into her den for winter. Wounded by pursuing birds (the stars Alkaid, Mizar, and Alioth), the bear’s blood dripped to Earth, staining the fall foliage red.

Come spring the bear will emerge from her slumber and begin to climb the northeastern evening sky.

The Moon

The moon will dominate the night sky worldwide this week as our natural night-light passes its full phase. During the summer months, the full moon was rising very late and climbing to a rather low maximum elevation in the night-time sky. But the arrival of autumn means that the much earlier sunsets will lift the full moon into view before 7 pm local time. It will culminate quite high above the southern horizon after midnight.

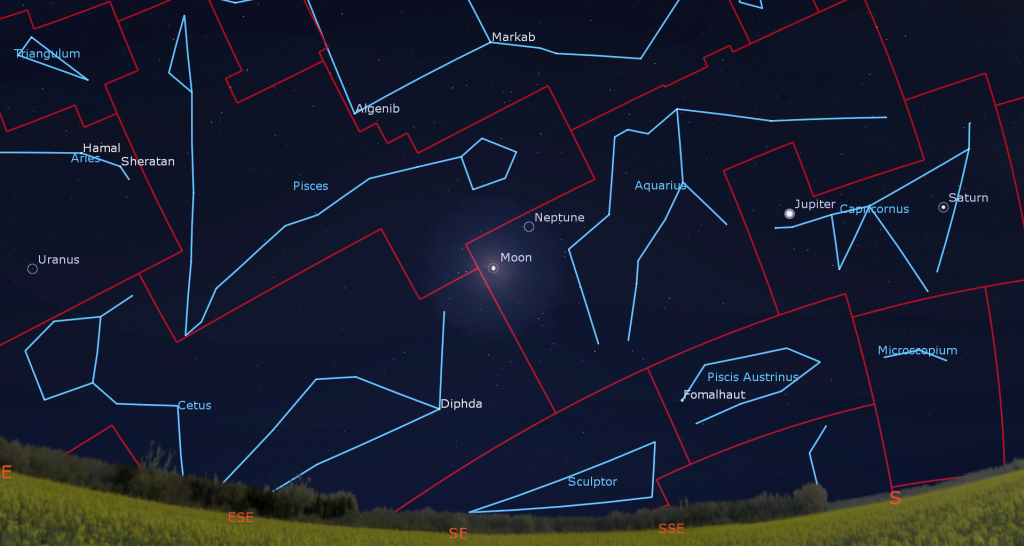

Tonight (Sunday) watch for the nearly full moon low in the eastern sky after dusk – already a healthy distance east of the bright planets Jupiter and Saturn it passed a few nights ago. After dark, the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will appear to the moon’s right (celestial west). Neptune will be a palm’s width to the moon’s upper right – but bright moons ruin Neptune-viewing. From Monday to Wednesday the moon will wade between the water constellations of Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale).

On Wednesday at 10:56 am EDT (or 14:56 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will officially reach its full phase. Since the full phase will occur in the morning in the Eastern Time Zone, folks there can see a slightly-less-than-full moon on Tuesday night, and a slightly-past-full moon on Wednesday night. Use your binoculars or a telescope to look for some texture in the craters along the moon’s left-hand (western) rim on Tuesday and along its right-hand (eastern) rim on Wednesday. Only people living in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Eastern Africa will see the moon rise when it’s precisely full.

The October full moon is traditionally called the Hunter’s Moon and, appropriately for Halloween season, the Blood Moon, or Sanguine Moon (not to be confused with an eclipsed “blood moon”). Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the October moon Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon – the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

When you face any full moon, the sunlight shining on it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on the full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! Now you can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then infilled with dark basaltic rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon later in the moon’s geological history. These “younger” areas have fewer impact craters on them.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of the impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon. There are smaller ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters punched into the maria have ejected dark rays on to white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock below, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. This 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Copernicus’ rays are squiggly, as opposed to Tycho’s arrow-straight ones. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highland’s anorthosite.

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enriched in the mineral titanium. That’s one of several reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to that location. Another is that its southern edge is close to the moon’s equator. Equatorial landing sites required less fuel and fewer course corrections of the spacecraft.

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than a lunar module descent stage. Only the cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment.

On Thursday night the waning gibbous moon will pass a few finger widths below Uranus in Aries (the Ram). From Friday to Sunday night, the moon will traverse the stars of Taurus (the Bull) – nearing the bright Pleiades star cluster on Friday, passing above the bright reddish star Aldebaran on Saturday, and ending the week between the stars forming the bull’s horns on Sunday night. Also during the coming weekend, the moon will be lingering into the morning daytime sky.

The Planets

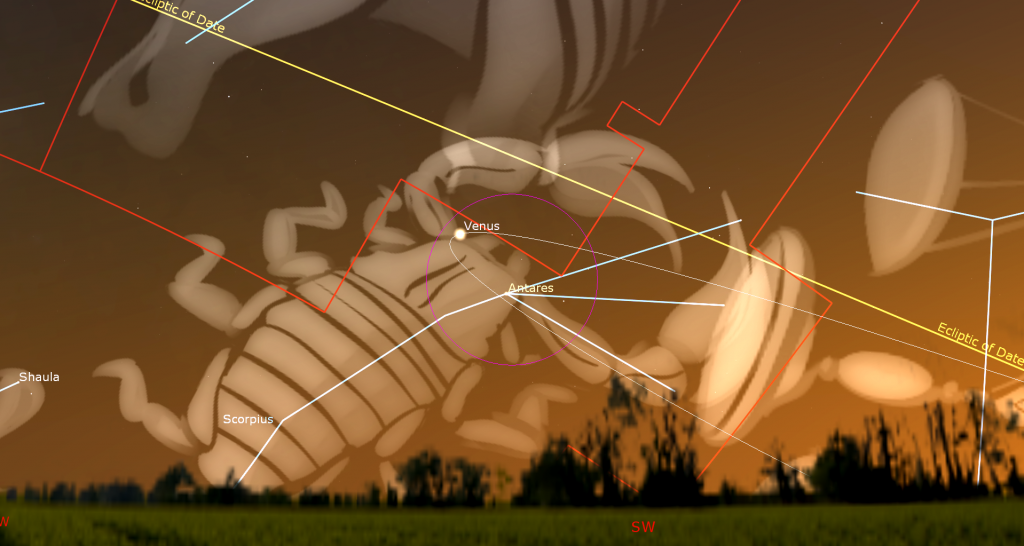

Our brilliant, but hot sister planet Venus will continue to blaze away in the southwestern sky this week. As the sky begins to darken before 7 pm local time, look for her sitting only a fist’s diameter above the horizon, and descending – barely higher than the neighbourhood houses or trees. Tonight (Sunday), Venus will be positioned about a thumbs width above (or celestial northeast of) the bright, reddish star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion). Their separation will increase every night as Venus travels east in its orbit while the sky migrates west, but they’ll be binoculars-close until Thursday.

Venus will set a little before 8:30 pm local time. The severely tilted evening ecliptic has kept Venus from climbing very high this year. Folks living at southerly latitudes, where the ecliptic is more upright, will see get to Venus higher, and shining in a darker sky.

When viewed in a backyard telescope Venus will look featureless because it is shrouded in thick, opaque clouds. But the planet will look barely more than half illuminated because Venus is nearing its widest angle from the sun, and is being illuminated from one side. Venus is also heading toward Earth now, so it will grow in size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A brighter sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily.

Jupiter and Saturn aren’t as bright as Venus. Once the sky gets a bit darker, turn toward the south-southeastern sky and look for those two planets sitting in the lower third of the sky. The bright white dot of Jupiter will be positioned 1.5 fist diameters to the left (or 15.5° to the celestial east) of the 18 times fainter, and yellow-tinted, ringed planet. At around 8:30 pm local time, they’ll reach their highest elevation in the sky, over the southern horizon, and then they’ll set in the west in the hours after midnight.

On Monday, Jupiter will appear to stop moving with respect to the distant stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) – marking the end of a westward retrograde loop that it began in June. You can watch Jupiter resume its regular eastward motion by noting its distance from the medium-bright star Deneb Algedi (or Delta Capricornus), sitting to its lower left (celestial southeast), decreases over the next month. The end of that loop, which was a parallax effect produced by our changing vantage point on the faster-moving Earth, means that both Jupiter and Saturn will be receding from us, and growing both less bright and smaller for the rest of this year.

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons and the belts tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night because Io orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. The other moons take between 3.5 and 16.7 days.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Monday (with Ganymede), Thursday, and Saturday, and in late evening on Wednesday (with Callisto) and Friday. It can also be observed after midnight tonight and Friday.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter’s disk between 11 pm EDT on Monday night and 2:15 am on Tuesday morning. Observers in western North America and the Pacific Ocean region can see Io’s smaller shadow join Ganymede’s shadow for about 15 minutes starting at 11:10 pm PDT (or 06:10 GMT on Tuesday, October 19). At the end of that double shadow transit event, Ganymede’s shadow will lift off Jupiter, leaving Io’s shadow to complete its solo transit at 1:25 am PDT. By then, Jupiter will have set for observers in the continental USA and Canada. Io’s small shadow will cross again, accompanied by the Great Red Spot, from 8:40 pm to 10:55 pm EDT on Wednesday night.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width. Iapetus is dark on one hemisphere and bright on the other, so it looks dimmer when it is east of Saturn, and it looks brighter when it is west of Saturn. Iapetus will reach minimum its brightness of magnitude 11.46 on October 29 and then double in brightness to magnitude 11.59 on December 8. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the left (celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Distant, blue Neptune is in the sky all night long, near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes) – and roughly three fist diameters to the left (or celestial east) of Jupiter. The main belt asteroid named (2) Pallas is not far away. This week, Pallas will be traveling downward (or southward) through Aquarius, about a thumb’s width to the right (celestial west of) the bright star Hydor.

Once again this week Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will be observable from late evening onward – especially after midnight, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky. Slow-moving Uranus is spending all of this year parked below the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), Hamal and Sheratan. It’s also positioned about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster.

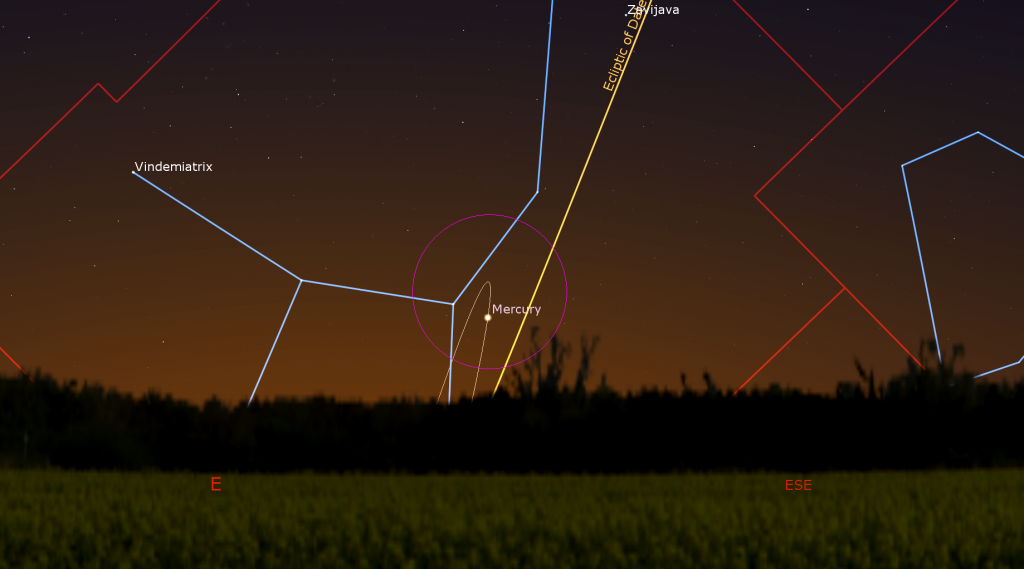

Mercury will be shining low in the eastern pre-dawn sky this week – in the opening stages of its best morning appearance for the year for Northern Hemisphere observers. The best time to see the magnitude 0.66 planet will be a few minutes before 7 am local time. It will become easier to see as it climbs higher each morning. Mars will join the morning sky in early November.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Tuesday night, October 19 from 8 to 9 pm EDT, SkyNews Magazine editor Allendria Brunjes and Canadian astrophotographer Paul Owen will host Subs and Stars – Lesson 2 of a free, eight-part online series that teaches people how astrophotos are built and edited. Details are here, and the registration link is here.

On Wednesday evening, October 20 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Dr. Keith A. Hawkins, Assistant Professor and Galactic Archaeology Lab leader at The University of Texas, Austin. His talk is titled Galactic Archaeology : Uncovering the Story of Our Home with Stellar Fossils. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here. The RASC Toronto Centre has an archive of their past meetings and guest lectures on their YouTube Channel here.

On Thursday, October 21 from 7 to 8 pm EDT, the Dunlap Institute at University of Toronto will stream their popular Astro Trivia Night. The live free event will feature lots of fun and prizes. Details are here. Watch it here.

Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but we are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO.

On Saturday night, October 23 from 7:30 to 9:00 pm EDT, the DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Dr. Joshua Speagle, a Banting and Dunlap Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto. He’ll speak on Mapping Our Milky Way Galaxy, how astronomers are piecing together the structure of our galaxy, even though we can’t view it from afar. There will also be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday October 20, 2021 at 3 pm. The registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, October 24 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, join us for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday October 20, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program you will be emailed information on the virtual program links and any specific information relating to your program. The registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday, October 26 when we’ll cover autumn binoculars stargazing. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!