Morning Zodiacal Light, The Great Bear Bows Down, and the Moon Passing the Sun Grants Views of Great Galaxies!

This terrific image of Jupiter was captured by my friend Claudio Oriani from his home in Richmond Hill, Ontario on September 5, 2023. More of his work can be enjoyed at his website https://www.wondersofthesky.com/about/

Hello, mid-September Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 10th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The morning zodiacal light will be visible from very dark sites and the moon will be absent from evening skies worldwide as it wanes toward Thursday’s new moon. That will allow us to view the big galaxies in the eastern sky – with only our eyes or with binoculars. Saturn is observable in evening, Jupiter joins it later, and Venus gleams at dawn. Meanwhile, the great bear enters her den. Read on for your Skylights!

The Big Bear Hibernates

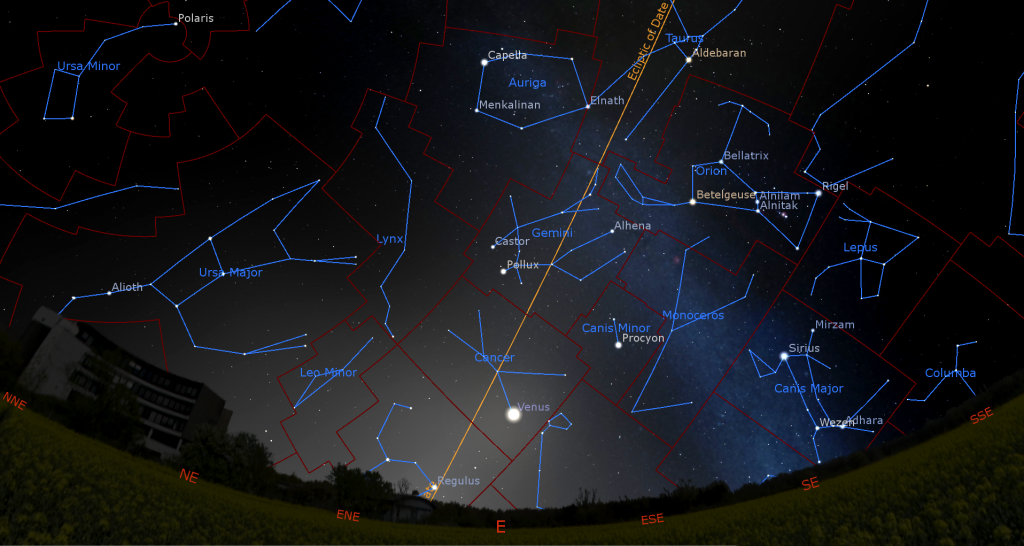

Have you tried looking for the Big Dipper lately? Around mid-September every year, that asterism, which is circumpolar for observers located north of 35° North latitude, reaches its lowest position above the northern horizon around midnight – as if it is scooping up a bowl of cold, refreshing northern water! Its stars might not even clear the treetops where you live.

North American indigenous traditions tell the tale of the Great Bear (Ursa Major) heading into her den for winter. Wounded by pursuing birds, represented by the Big Dipper handle stars Alkaid, Mizar, and Alioth, the bear’s blood dripped to Earth, staining the fall foliage red. Come spring, the bear will emerge from her slumber and begin to climb the northeastern evening sky.

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint Zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers north of 60°N latitude miss out.

If your location favours it, on mornings between now until the full moon on September 29 look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky below the very bright planet Venus, which may suppress the phenomenon. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which will be positioned nearby in the southeastern sky.

The Moon

The moon will steer clear of the evening sky worldwide this week while it visits the sun, allowing us another chance to appreciate the late summer sky and the majestic Milky Way.

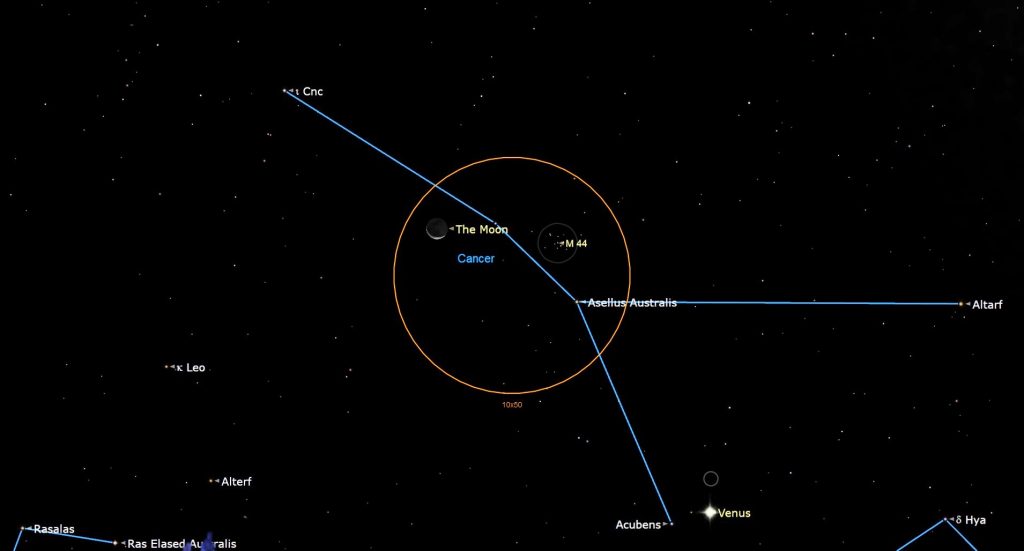

On Monday morning, the moon’s pretty, waning crescent will rise around 3 am local time, accompanied by the brilliant planet Venus and the winter stars and constellations. The big open star cluster in Cancer (the Crab) known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44 will be positioned several finger widths to the moon’s lower right (or 3 degrees to the celestial south). The moon and cluster, which is more than twice the size of the moon, will be close enough to share the field of binoculars, but you’ll see more of the “bees” if you tuck the moon just out of sight on the left and view them before the morning sky starts to brighten. Venus will remain about a fist’s diameter below the cluster on the following mornings when the moon has moved on. Another, smaller cluster named the Golden-Eye cluster or Messier 67 will be located a short distance above Venus.

On Tuesday morning, the moon will hop east to shine to Venus’ left in Leo (the Lion). That morning will be a great time to watch for Earthshine on the moon, especially around 6 am local time. Also known as the Ashen Glow and “The old moon in the new moon’s arms”, it’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere.

On Wednesday morning before dawn, the even slimmer crescent moon will shine near Leo’s bright star Regulus. You may to walk around a little to spot them between the trees or houses. That will be our last glimpse of the moon for this lunar month.

On Friday, September 15 at 01:40 Greenwich Mean Time, which converts to Thursday at 9:40 pm EDT or 6:40 pm PDT, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will still be located in Leo, 2 degrees north of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day – unless there is a solar eclipse, as there will be at the next new moon on October 14!

The moon will rejoin the western evening sky, within the borders of Virgo (the Maiden), on Friday after sunset. But it won’t shift far enough east of the sun to become visible until Saturday and Sunday, when its slender young crescent will lurk above the western horizon for a brief period after sunset.

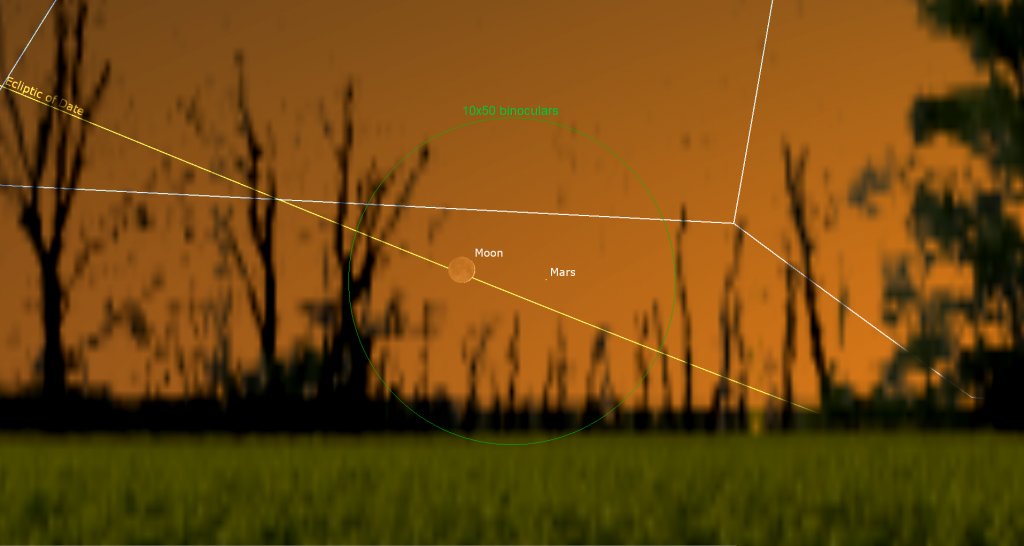

For a challenge, wait until the sun has completely set on Saturday and then seek out the faint dot of Mars located just a thumb’s width to the right (or celestial northwest) of the moon – close enough to share the view in binoculars or a backyard telescope. Observers in the southern USA and tropical latitudes will see them more easily. The moon will pass in front of (or occult) Mars in daytime for most of North America (except western Mexico), the Caribbean, and Central America. Observers in northern South America will be able to see that event in a darker sky.

The Planets

Have you checked out Saturn in your telescope lately? Its narrower rings this year and its availability for viewing as soon as the sky starts to darken after sunset every night might be the impetus you need to buy a telescope! Both Jupiter and Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure from now until mid-winter! And once you get more proficient with it, you can seek out fainter Uranus and Neptune near the two bright gas giants.

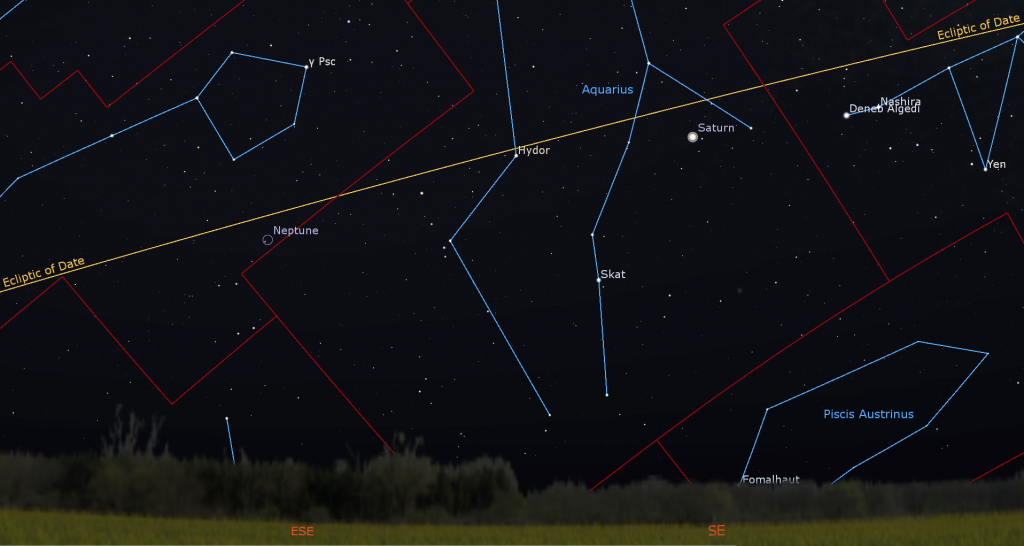

Saturn’s creamy-yellow dot will pop into view a small distance above the southeastern horizon soon after sunset. Recently past opposition, the ringed planet will shine all night long as it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope when it is higher in the sky – say after 9 pm local time. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be shining to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle well above, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be off to the planet’s upper left. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn all year long.

Saturn’s beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the planet’s lower left (celestial east) tonight (Sunday) to Saturn’s upper right (celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely.

This summer the blue ice giant planet Neptune, currently 840 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Tonight, the planet will slip very closely past a brighter star named 20 Piscium, but they’ll be binoculars- and telescope-close for some time. (Neptune moves slowly because it is so far from the sun.)

Brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 19 times brighter than Saturn, will be rising around 9:30 pm local time this week, but it will take until about 10:30 pm before it can clear the eastern rooftops. Good telescope viewing time will begin around 11 pm. Not to worry, though – that window will start earlier and earlier in the coming weeks. This year Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter will spend the wee hours of the night following Saturn across the sky, then it should catch your eye while it gleams high in the southwestern sky before sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter on Saturday night. This week, Jupiter’s westerly retrograde motion will carry it close to a bluish star named Sigma Arietis (or σ Ari). While the star will appear about as bright as one of Jupiter’s moons, it will shine above (celestial north of) their line. The star and Jupiter’s retinue will be telescope-close all week, and closest next Sunday night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk late Eastern Time on Monday, Thursday, and Friday night, in the wee hours on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday. It’ll appear before dawn on Wednesday, Friday, and next Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday morning, September 11, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 3:14 to 5:19 am EDT (or 07:14 to 09:19 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again on Tuesday night, September 12 from 9:44 to 11:48 pm EDT (or 01:44 to 03:48 GMT on Thursday). On Friday morning, September 15, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere with the Great Red Spot from 3:10 am to 5:24 am EDT (or 07:10 to 09:24 GMT). (These times may vary by a few minutes.)

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week Uranus will be located a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s lower left (or 7.6° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. I’ll get more specific in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

Brilliant Venus will be shining in the eastern pre-dawn sky from now until January, climbing farther from the sun with each passing day. This week Venus will rise among the stars of Cancer (the Crab) at about 4 am local time. Early risers can enjoy the winter constellations and stars nearby, and the Golden-Eye open star cluster just above Venus that I mentioned above. Viewed in a telescope this week, our sister planet will exhibit a large disk and a very slim waxing crescent phase. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

Mars is too close to the sun to be seen easily after sunset nowadays, but you can try to see it near the moon on Saturday, as I mentioned above. Mercury will be shining just above the eastern horizon before sunrise this week.

Giant Galaxy Gazing on Moonless Nights

It’s time to look for the farthest object a human eyeball can see without assistance* – the Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31. This large spiral galaxy is a big sister to our own Milky Way galaxy. It sits 2.5 million light-years away from our sun, meaning that its stars’ light has been journeying for that length of time. And, if there are alien astronomers living there and looking back at us with super-deeper telescopes, they are seeing our solar system as we appeared 2.5 million years ago!

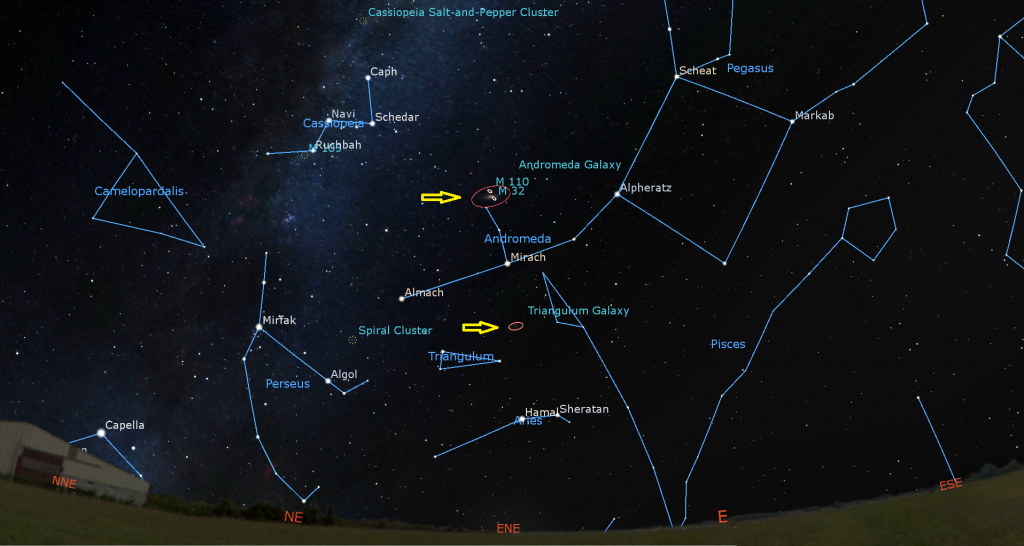

In mid-September, the Andromeda Galaxy sits just less than halfway up the east-northeastern sky at 9 pm local time. (It will be higher later on.) To locate it, you can first find the medium-bright star Mirach. It’s the second star when hopping left (celestial east) from Alpheratz, which marks the eastern corner star of the Great Square of Pegasus. Then look for a dimmer star shining a few finger widths above (or 4° NE of) Mirach. The Andromeda Galaxy is higher again by that same distance. Alternatively, you can use the highest three stars of the W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). They form an arrow that points directly at M31.

Under dark skies, using your unaided eyes only, you should be able to see a faint fuzzy patch that is elongated left to right. Try directing your attention a little ways away from the galaxy and it will brighten – the averted vision trick! The galaxy spans six full moon diameters across the sky, but only its bright core and the surrounding, inner halo are usually seen visually. The galaxy is quite easy to see with binoculars. The giant galaxy is a cool object to see! Let me know if you view it.

Because telescopes have fields of view that are too narrow to see the entire galaxy, they’ll generally only show you Andromeda’s bright core. While looking, see if you can make out M31’s two small, fuzzy-looking companions, the small elliptical galaxies designated M32 and M110. M32 is closer to the main galaxy’s core and it situated just to the lower right (or to the celestial south). M110 is above (or northeast of) the main core and is slightly farther away. At 2.49 million light-years, M32 is closer to us than the Andromeda Galaxy; while M110 is 200,000 light-years farther away. (Most telescopes will flip and/or mirror image those directions.)

*Another large galaxy, called Messier 33 in Triangulum (the Triangle), is 2.75 million light-years away. Observers with very keen eyes under very dark sky conditions can sometimes see it, too – setting the record. This galaxy is tougher because it is oriented nearly face-on to Earth – so its light is spread across a large patch of sky (equal to 1.5 full moon diameters), making it dimmer overall. It sits only 1.3 fist diameters below M31, a palm’s width below the star Mirach.

Cepheus the King of the Pole

If you missed last week’s tour of the circumpolar constellation of Cepheus (the King), the king of the North Pole, I post it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!