Northern Winter Nigh, Minimal Meteors, the Evening Moon Waxes to Yule, and Christmas Lights!

My friend Alan Dyer of Alberta captured this spectacular image of a lone Geminids meteor streaking across an aurorae-filled sky on December 13, 2023. From Collingwood, Ontario I saw two terrific Geminids in one hour on December 14. Follow Alan’s @amazingskyguy account on X.com and visit his ww.amazingsky.com page for more.

Hello, Start-of-Winter Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 17th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will appear in the evening sky this week while it waxes toward full at Christmas. In the meantime, it will pose with some bright planets, beckon close-up views of its spectacular surface, and climb to its highest point in the December sky. The moon will also put a damper on the weak Ursids meteor shower. Winter will commence in the north on Thursday, and I review some candidates for the Christmas star story. Read on for your Skylights!

‘Tis the Seasonal Change

Happy Holidays, everyone! Or, as we astronomers say, “Have a Happy Solstice and a Merry Perihelion!”

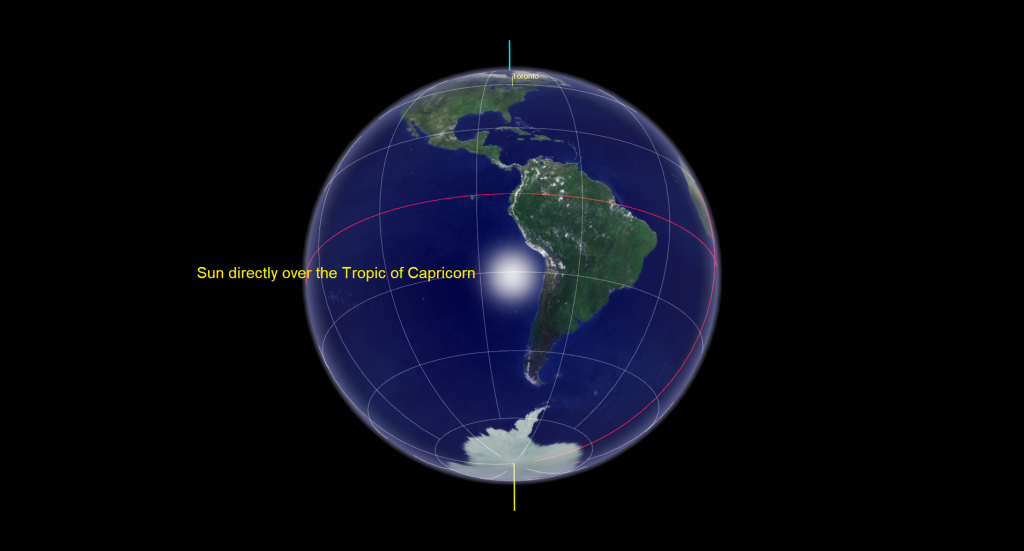

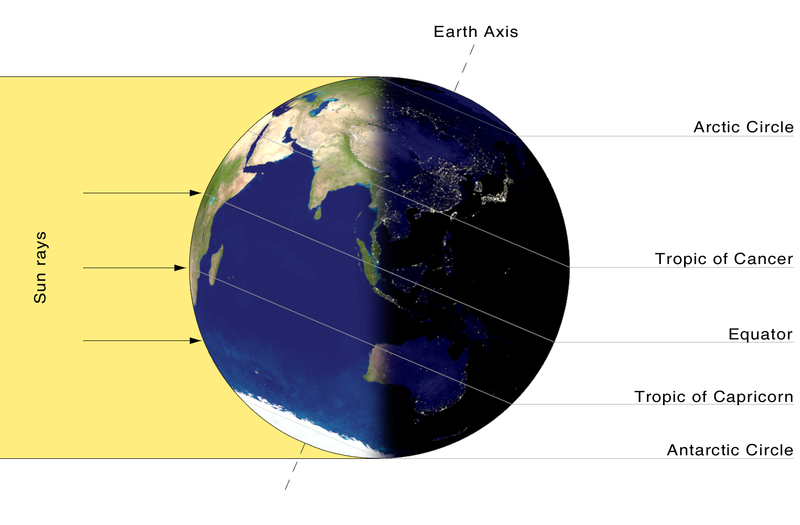

The December, or winter solstice, will officially occur on Thursday, December 21 at 10:27 pm EST and 7:27 pm PST. That converts to 03:27 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday, December 22. At that time, the northern pole of Earth’s axis of rotation will be tilted by its maximum amount of 23.5° away from the sun. The solstice marks the beginning of winter for the Northern Hemisphere – but not winter weather, as I’ll discuss below. On the day of the winter solstice, the sun’s highest point in the daytime sky, which always occurs at local noon, is lower than on any other day of the year. That is because the sun is farthest south of the celestial equator in the sky. (An object’s highest position in the sky is called its culmination.)

Astronomically, the sun will reach its greatest southern declination and its greatest angle from the celestial equator. The observation that the sun temporarily stopped moving in declination (its north-south component of motion compared to the fixed stars) on that date is reflected in the name solstice, which arises from the Latin expression sol sistere, ”the sun is standing still”.

At the December solstice, the points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets are shifted well south of east and west, so the arc that the sun traces out across the daytime sky is shorter than on any other day of the year – requiring the least amount of time to make that crossing. With noon still pinned at mid-day, it’s the sunrise and sunset times that are later and earlier, respectively – so Northern Hemisphere dwellers receive the shortest duration of daylight and the longest night for the year.

The daytime arc of the sun continues to shorten as you move farther north on Earth – until you reach the Arctic Circle latitude at 66°33′48.4″ North. At sea level anywhere along that ring around Earth, the sun won’t rise at all on the solstice – but you would still see a twilit sky during the noon hour. Residents living above about latitude 80° N experience 24 hours of darkness, which lasts until the sky begins to brighten ahead of the March equinox. That is great for astronomy if you and your equipment can stand the cold!

The sunlight that northerners receive this at time of year is weaker in intensity because it’s spread over a larger area, just as a flashlight beam looks dimmer when you shine it obliquely at a wall as opposed to directly at it. Try it! On the December solstice, the sun will be directly overhead at noon if you live along 23° 26’ 11.2” S latitude, otherwise known as the Tropic of Capricorn. The sunlight’s intensity weakens more and more as you travel farther from that latitude. (The Tropic of Cancer works the same way for the Southern Hemisphere, but on the June solstice.) In antiquity, when those tropics first became understood by astronomers/astrologers, the sun resided in those two constellations on the solstices. The precession (or slow wobble) of the Earth’s axis of rotation has shifted the celestial positions of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes, varying the precise latitude of the two tropics.

Fewer daylight hours and weaker sunlight results in less received solar energy (insolation) and therefore colder temperatures! It is not the case, as some people think, that days are colder in winter because Earth is farther from the sun (a position called aphelion). That event happens every year in early July. On the contrary – Earth’s minimum distance from the sun (perihelion) occurs every January 4, give or take a day. In 2024 that will happen late on January 2.

After Thursday, northern daylight hours will slowly start to increase again. For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun will attain its highest noon-time culmination for the year on the December solstice, and kick off their summer season. Their winter will commence six months from now, at the June solstice.

Some scholars think that Christmas was deliberately scheduled close to the winter solstice, and Easter close to the vernal equinox, because the early non-Christian “pagans” were already holding celebrations at that time to mark the astronomical changing of the seasons.

The dates that the equinoxes and solstices land on vary a bit due to Earth’s non-integer number of days in the solar year. They get reset after a leap year correction. The meteorological definition of winter is December 1 to February 28/29, when the mean temperatures are coldest.

Christmas Star Candidates?

Sirius, the brightest star in Canis Major (the Big Dog) and the brightest star in the night sky worldwide, will be shining above the southeastern horizon by about 8:30 pm local time this week. Sirius is hard to miss once it clears the trees and rooftops. If you are walking through your darkened house in the middle of the night, the star might catch your eye out a window because it never climbs very high. It will culminate in the lower part of the southern sky at about 1 am local time this week.

Sirius is a hot, blue-white, A-class star located a mere 8.6 light-years away from our sun. Its extreme brightness and low elevation in the sky combine to produce spectacular flashes of color as it twinkles. A very large telescope may allow you to see Sirius B, a faint white dwarf companion star located just 10 arc-seconds east of Sirius. (Remember to account for how your telescope flips the scene.)

Cold Weather Astronomy Tip: If you plan to use your telescope on winter evenings, set it outside in a safe location (even an unheated garage or car trunk will do) for at least a couple of hours ahead of time. That will allow the air trapped inside it to chill down to ambient, reducing the turbulent “tube currents” that distort the images. Leave all the lens caps in place until viewing time to prevent frosting on the glass elements. And put those caps back on before bringing it back inside at the end of the session. Better yet, zip it into its case or snug a plastic bag around it while still outside. That way, the warm house air cannot condense on it.

With Venus continuing to gleam in the southeastern sky before sunrise for most of this winter, its easy to imagine that sky-watchers of old could be captivated by Venus’ brilliance and declare it the “Christmas Star”. But Venus puts on those celestial showings, in the east before sunrise or in the west after sunset, every two or three years – hardly a rare occurrence.

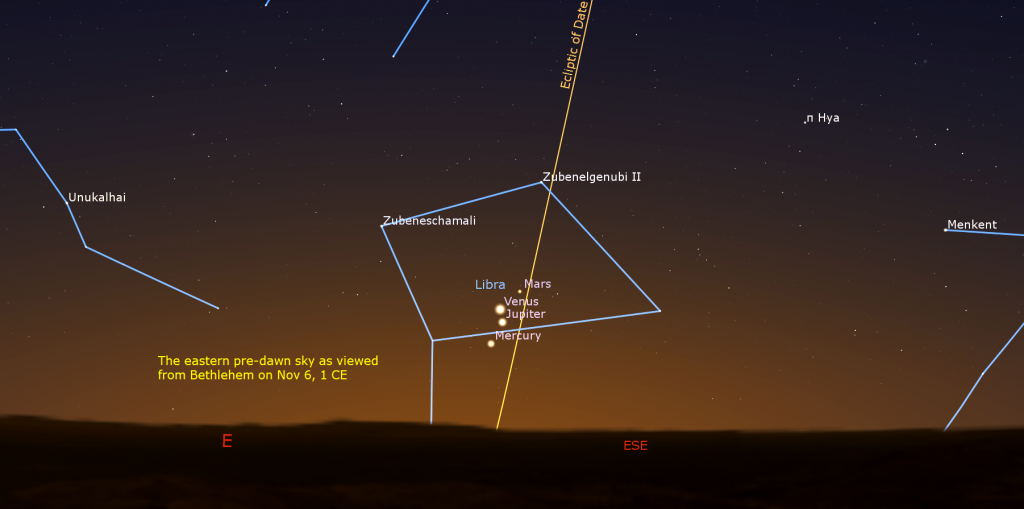

The event that may have spawned the biblical story of wise men following a star in the east, was a rare planetary conjunction of Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus that occurred in the eastern pre-dawn sky in early November of the year 1 CE. In fact, on one of those mornings, Venus and Jupiter were so close together that they might have looked like a single, extra-bright object! For about a week, all four bright planets were grouped into a stubby line that spanned less than four fingers widths in length. The next time you see bright Venus, imagine how impressive those other planets gathered around her would have looked.

Alternate explanations for the Christmas star include a bright supernova or a passing comet. Both would be memorable, rare, and temporary, but we have not yet found a supernova remnant that matches the required location in the sky, and surely a bright comet’s tail would have been mentioned by the observers!

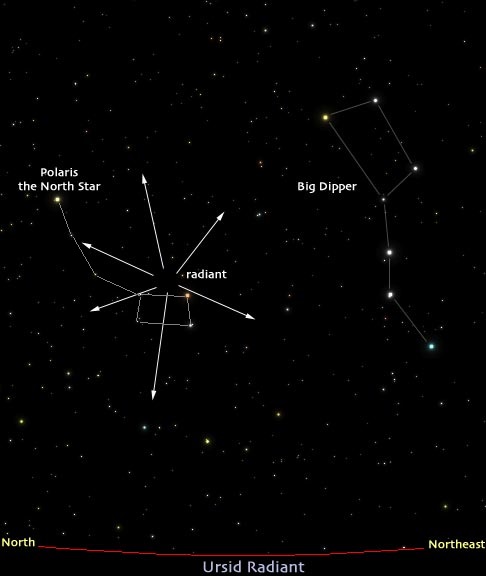

Ursids Meteor Shower Peak

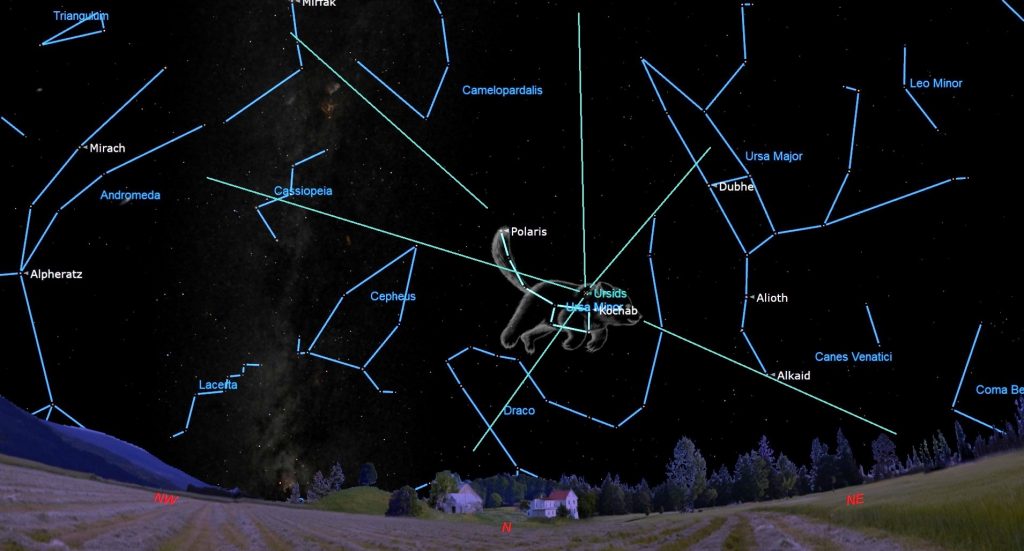

The Ursids meteor shower, which is produced by particles of debris dropped by the periodic comet 8P/Tuttle, runs from December 13 to 24 every year. The weak, short-duration shower will peak (usually with only 5 to 10 meteors visible in an hour) while Earth is traversing the densest part of the debris field on Friday evening, December 22 in the Americas. The better time to watch for Ursids meteors will be the hours after midnight on Saturday morning, especially after the bright moon sets around 4 am local time. You can also try to stand where the moon is hidden behind a tree or building. True Ursids will appear to travel away from a position in the sky near the North Star Polaris, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky.

I shared some meteor shower viewing tips last week here.

The Moon

The moon will be bright and full over Christmas this year. In the meantime, Earth’s natural night-light will grace the evening sky worldwide as it waxes in phase. This will be the best week of the lunar month to view the moon under magnification by binoculars or a telescope.

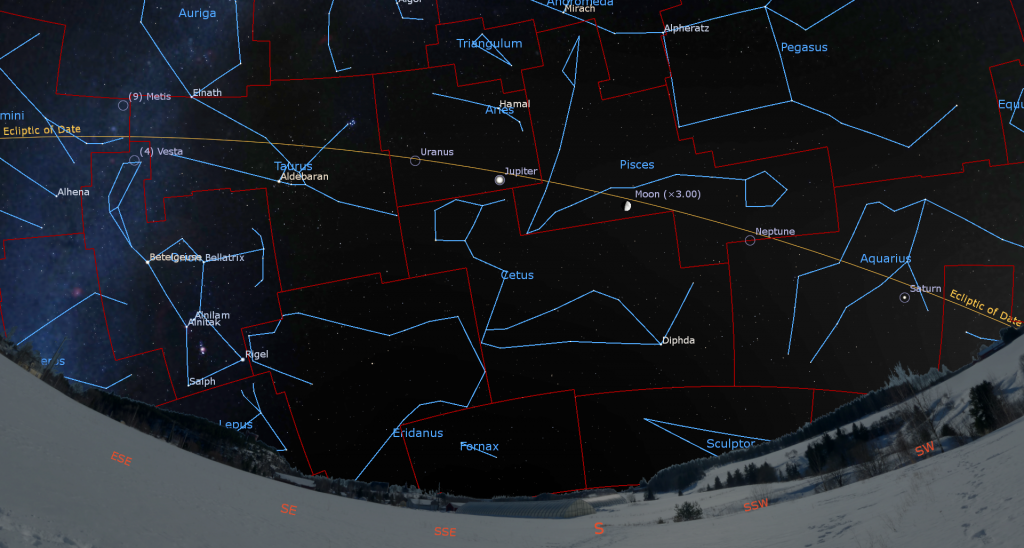

Tonight (Sunday evening) the pretty, 29%-illuminated crescent moon will shine among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and only a few finger widths below (or 3° to the celestial south of) yellowish Saturn. The pair will be cozy enough to share the field of view in binoculars until they set in the west around 10 pm local time. By then, the moon’s easterly orbital motion and the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift Saturn to the moon’s right. You can use binoculars to search for Saturn above the moon even before the sky fully darkens.

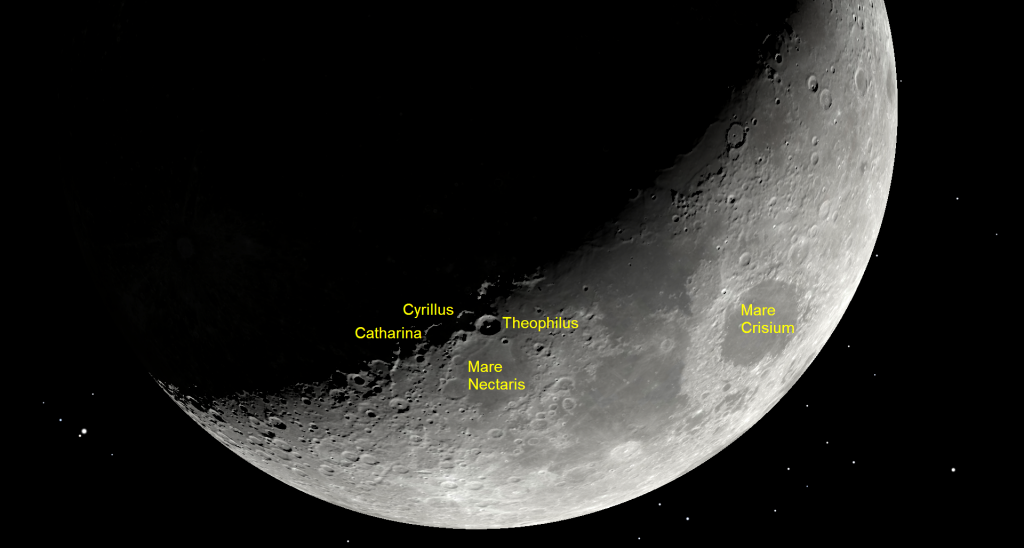

Also tonight, the terminator will fall just to the west of a trio of large craters named Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina that curve along the western edge of round, gray Mare Nectaris to their lower right (or lunar east). You can tell what order those craters were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way it has partially overprinted neighboring Cyrillus to its lower right (lunar southwest). Under magnification, Theophilus’ terraced rim and craggy central mountain peak are evident. Cyrillus hosts a trio of degraded central peaks inside a hexagonal rim, while much older Catharina’s peak has been submerged, her edges blurred and her floor overprinted by smaller, more recent craters.

On Monday evening, the moon will remain in Aquarius, now positioned just to the upper right (or celestial north) of the trio of medium-bright stars named Psi Aquarii. Your telescope will nicely show the contrast between the rough and highly cratered lunar highlands and the smooth, grey floor of Mare Serenitatis. The trio of craters you viewed on Sunday will be in full sunlight.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its 29.53-day journey around Earth on Tuesday at 1:39 pm EST, 10:39 am PST, and 18:39 GMT. At first quarter, the moon’s 90-degree angle from the sun causes us to see it half-illuminated on its eastern side. First quarter moons always rise around mid-day and set around midnight, so they are also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. The half-moon will be occupying western Pisces (the Fishes) with Neptune, but that planet will be hard to see next to the bright moon. The moon will spend Wednesday and Thursday in Pisces, too.

Even before the sky fully darkens on Thursday, the bright, waxing gibbous moon will catch your eye in the southeastern sky along with the dazzling planet Jupiter to the moon’s lower left. As they cross the sky together overnight, the moon’s easterly orbital motion will carry it closer to Jupiter. Meanwhile, the diurnal rotation of the sky will swing Jupiter above the moon before they set in the west around 2 am local time on Friday morning. On Friday evening, the show will repeat with the moon now to Jupiter’s left (or celestial east). Jupiter will sit below the moon when they set in the wee hours of Saturday.

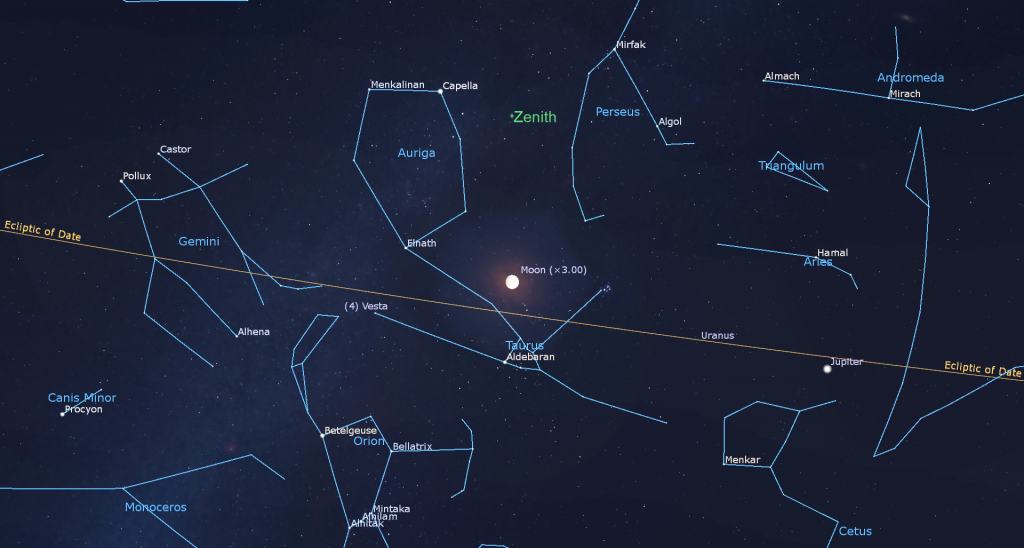

On Saturday, the 90%-illuminated moon will rise in mid-afternoon. Saturday’s moon will be entering Taurus (the Bull) for a weekend stay. Once the sky darkens, only the Jupiter and the brightest stars will be able to compete with the moon’s brilliance.

The Winter Football, also known as the Winter Hexagon and Winter Circle, is an asterism composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major (the Big Dog), Orion (the Hunter), Taurus (the Bull), Auriga (the Charioteer), Gemini (the Twins), and Canis Minor (the Little Dog) – specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. All of those stars will have cleared the horizon in the southeastern sky by 8:30 pm local time. When the star pattern stands upright in the south towards midnight, it will encompass an area of the sky 45 degrees wide and 66 degrees high (or 4.5 by 6.5 fist diameters) – it’s huge! The oval is visible during evenings from mid-November to spring every year.

Next Sunday night, December 24, the bright, nearly full moon will shine along the right-hand (or western) edge of the football, between Capella and Aldebaran. The moon will journey through the football until the following Wednesday night. Because the ecliptic sweeps through the upper half of the asterism, the moon glides through the shape every month in the winter months. When the moon isn’t so bright, the Milky Way can be traced vertically through the asterism. By the way, the shape can also be seen from the Southern Hemisphere in late evening at this time of year – only it’s inverted.

The Christmas Eve moon will also perch extra high in the sky around 11 pm local time. That’s because the daytime ecliptic will be only days past its lowest, the nighttime ecliptic highest, and the moon’s orbital inclination will add another 3.5°, or several finger widths, to its elevation when it culminates a short time before 11 pm local time. It will be giving “a lustre of midday to objects below” to quote Clement Clarke Moore.

The Planets

Mercury and Mars are hiding next to the sun nowadays. Mercury will be approaching the setting sun until Friday, while Mars will be extending its angle from the eastern pre-dawn sun during the winter. When speedy Mercury overtakes Mars late this month, observers in some parts of the world might catch a glimpse.

As I mentioned above, the crescent moon will shine next to Saturn’s dot starting at dusk tonight (Sunday), then it will wend its way over to Jupiter and Uranus. When Saturn appears in the evening twilight, it will already be at its highest point, due south – its best telescope viewing time. Then the planet will sink westward to set around 10 pm. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) are sprinkled to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east) and the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) flicker to Saturn’s lower right (or west). But they won’t be easy to see while the bright moon is shining.

Our opportunity to view Saturn will diminish as the planet shifts incrementally sunward each night over the coming weeks – so take the first opportunity! If you are lucky enough to get a telescope for the holidays, Saturn could be your first target. It never disappoints!

Even powerful binoculars can show that Saturn has rings. Any size, style, or brand of telescope will show them well. From Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° is letting us see the top of its ring plane, and allowing its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the far left of Saturn (or celestial east) tonight, crossing below Saturn on Wednesday-Thursday, and then to a position far to the right of the planet (or celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

The ice giant planet Neptune, currently 625 times fainter than Saturn, has been following Saturn across the sky every night this year – but I suggest scheduling your view of the planet on a future night without so much bright moonlight.

Very bright Jupiter, which is rising in mid-afternoon lately, will grab your attention in the lower part of the eastern sky starting at sunset. The planet will climb to a position relatively high in the southern sky around 8:45 pm local time (its peak telescope-viewing time) and then set in the west by about 3:30 am. The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) named Hamal and Sheratan, will shine a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter. The stars forming the Great Square of Pegasus will be higher and to the right, but this week’s bright moonlight will hide them.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line flanking the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will be huddling to Jupiter’s right tonight (Sunday) and next Sunday.

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. It’ll appear late on Monday and Wednesday night, and also during the wee hours of Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Wednesday morning, December 20, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern latitudes, with the Great Red Spot, from 1:10 to 3:20 am EST (or 06:10 to 08:20 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter with the Great Red Spot on Wednesday evening, December 20 from 11:28 pm to 1:34 am EST (or 04:28 to 06:34 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again on Friday, December 22 from 5:58 to 8:04 pm EST (or 22:58 to 01:04 GMT). On Saturday evening, December 23, sky-watchers located in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Africa can watch two shadows crossing the southern hemisphere of Jupiter at the same time for about 25 minutes. At 8:25 pm Central European Time, the small shadow of Europa will join the much larger shadow of Ganymede, which began its own crossing of the planet’s south polar zone 70 minutes earlier. Ganymede’s shadow will leave Jupiter at 8:49 pm CET, leaving Europa’s shadow to continue on alone until 10:42 pm CET. Watch for Europa itself to move off of Jupiter’s disk by 8:35 pm CET. (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Uranus has been following Jupiter across the night sky, too. During evenings this week, the blue-green planet will be positioned 1.4 fist diameters to Jupiter’s lower left (or 13.9° to the celestial east) in eastern Aries. The bright Pleiades star cluster will also be located a generous fist’s width to Uranus’ left (or 11° to the celestial northeast). At magnitude 5.6, Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes – some people have even been able to spot the planet with their unaided eyes. This week’s bright moon will spoil the fun.

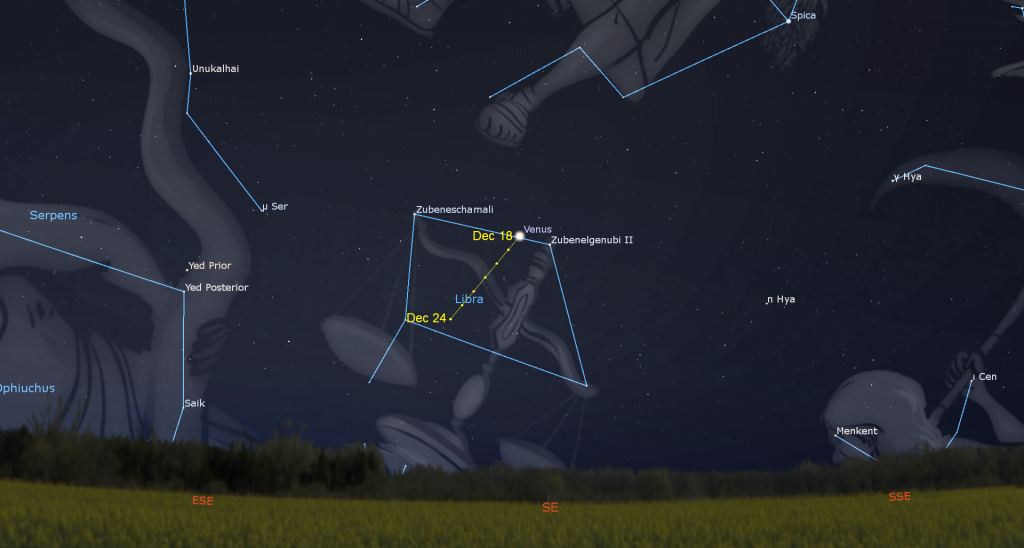

The brilliant planet Venus is gradually sinking sunward and dropping a little lower each morning. It will occupy the southeastern sky before sunrise for another couple of months. If you head out before dawn, you can see the brightest stars of Libra (the Scales) shining around our sister planet. Venus will descend through Libra (the Scales) through the end of the year. Viewed through a telescope this week, our next-door planet will show a shrinking, waxing gibbous disk spanning 14.9 arc-seconds.

On Thursday, Earth’s orbital motion will carry us between the minor planet Vesta and the sun. Because it will be opposite the sun in the sky and closer to Earth, Vesta will be visible all night long, and shine at its brightest for the year (magnitude 6.2) – within reach of binoculars and small telescopes. Look for the asteroid near the raised club of Orion (the Hunter), below the midpoint between Nu Geminorum (or v Gem), the star that marks Castor’s lower foot and Zeta Tauri, the lower horn-tip star of Taurus (the Bull). Vesta’s trajectory over the next couple of weeks will carry it toward Zeta Tauri.

Watch Algol Brighten

Another fine opportunity to watch the star Algol vary in brightness will arrive tonight, Sunday evening, December 17 in the Americas. At 6:17 pm EST the star will be positioned about halfway up the eastern sky, shining at its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4, which is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star that sits just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or celestial south). Five hours later at 11:17 pm EST, Algol will be high in the western sky and shining at its full intensity of magnitude 2.1, similar to the medium-bright star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae), which will be located a generous fist’s diameter below Algol. I wrote more about Algol last week here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!