Betelgeuse Blinks, Moonless Maximum Meteors for 2023, Algol Alternates, and Pursuing Planets!

This terrific composite image of the Geminids meteor shower in 2017 was taken by Alan Dyer of Alberta. The winter Milky Way descends through the centre and the bright patch at right is Orion’s belt and sword. More of Alan’s images can be viewed at his website https://amazingsky.photoshelter.com/index

Hello, Mid-December Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 10th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will remain out of the evening sky for most of this week while it passes the sun. That will give us all a terrific moonless Geminids meteor shower peak at mid-week, and more opportunities to delight in the jewels of the winter constellations. Speaking of that, parts of the world can watch an asteroid pass in front of Orion’s bright star Betelgeuse on Tuesday, dimming its light. The variable star Algol will vary during evening for observers in the Americas, and the four big planets and Venus will welcome your attention in evening and morning, respectively. Read on for your Skylights!

Earliest Sunset

If you live anywhere on Earth around the latitude of Toronto, Canada, i.e., about 44° N, you’ll have the earliest sunsets of the year this weekend – at 4:40 pm local time. A week from now, sunset will be about a minute later, but that pace will ramp up every week. The total amount of daylight each day will continue to shrink until the solstice on December 22, and then the daylight hours will start to increase again.

An Asteroid Blinks Betelgeuse

For lucky folks located on a narrow track that passes from central Asia through Turkey, across Greece, Italy, and southern Spain, and then Florida and central Mexico, a main belt asteroid named (319) Leona will pass in front of, or occult, the bright star Betelgeuse in Orion on Tuesday, December 12 around 8:17 pm EST or 08:17 GMT. For several seconds, Betelgeuse will fade or wink out altogether.

Many astronomers will be recording the event to learn more about the asteroid’s shape and the star’s atmosphere. Amateurs can easily view or video the event in a backyard telescope, too. There is a detailed story about the rare event at https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/asteroid-will-cover-betelgeuse-may-reveal-its-visible-surface/. If you are located elsewhere, consider tuning into a live stream of the event from Virtual Telescope or other sources.

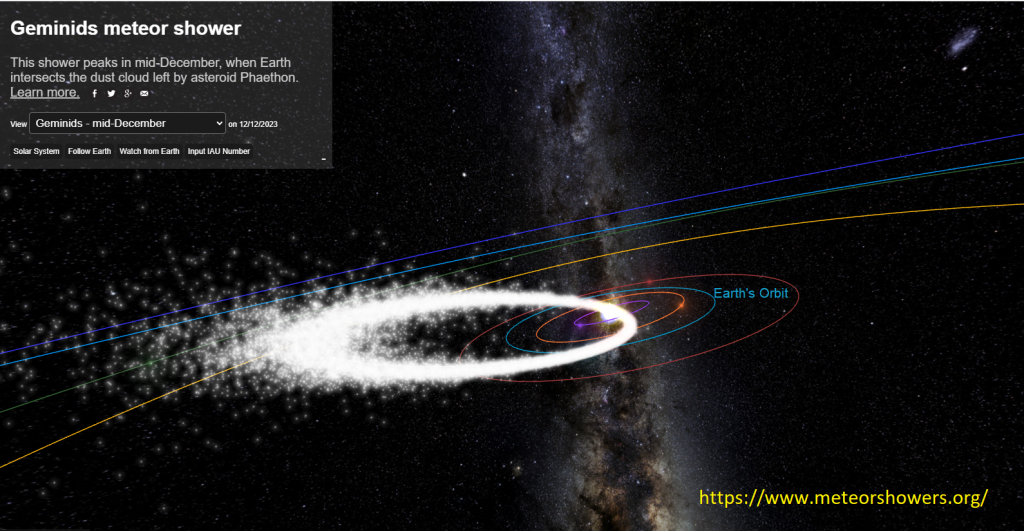

The Geminids Meteor Shower

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through zones of debris left in interplanetary space by periodic comets (and, in some cases, asteroids). Over many, many years, the 1-2 gram-weight particles that range in size from sand grains to small pebbles, accumulate and spread out into an elongated “cloud” along the comet’s orbit. (A good analogy is the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets quite dirty if the truck drives the same route many times!) If Earth’s orbit intersects a comet’s orbit, we experience a meteor shower. Showers repeat annually when Earth returns to the same location in space on the same date every year.

As we traverse the debris, Earth’s gravity pulls on the particles, and they burn up as “shooting stars” while falling through Earth’s atmosphere at speeds between 40,000 and 256,000 km/h. Each particle’s kinetic energy ionizes the air molecules it encounters, leaving a long trail of glowing gas that is less than a metre in diameter, but many kilometres long. Most trails occur in the thermosphere, the region of our atmosphere between 80 and 120 km above the ground. Slower meteors need to reach the denser atmosphere at lower altitudes before they will form a trail. Viewed from the Earth’s surface, on a clear, dark night, we see the meteors glowing briefly as they streak across the sky – but those “shooting stars” have nothing at all to do with the distant stars of our galaxy. Your favourite constellations will look the same after the shower.

The duration and intensity of any shower depends on the breadth of the particle cloud, whether we traverse it obliquely or straight across it, and whether we pass through the core or merely skirt its edge. The quality of a shower also depends on whether the moon is absent (yay!) or present and bright (boo!). For any given shower, the moon phase varies from one year to the next.

If you think of the Earth as a car speeding around the sun, the meteors are like bugs hitting its windshield. The constellation that our “car” is driving towards during the shower’s active period gives the shower its name. Meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but the members of a given shower will all appear to be streaking away from a particular location in the sky, called the radiant, that lies within a particular constellation. (This direction-of-travel rule can be broken when two showers are underway at the same time, and also by random meteors, called sporadics, which aren’t part of the main debris field, but instead are isolated particles drifting in interplanetary space.)

The Geminids Meteor Shower, always one of the most spectacular of the year, runs from November 19 to December 24 annually. The Geminids will deliver a peak number of meteors after midnight on Wednesday night, December 13, when up to 120 meteors per hour are possible under dark sky conditions. To be clear – that’s a maximum of two meteors per minute – and not the steady stream of them you might see in long-exposure photos and videos you see on social media or on weather channels. Geminids meteors are often bright, intensely coloured, and slower moving than average because they are produced by sand-sized grains dropped by an asteroid designated 3200 Phaethon. The shower will rapidly taper off during the following days.

The best time to watch for Geminids will be from full darkness on Wednesday evening until dawn twilight on Thursday morning. In 2023, there will be no moonlight to spoil the show! At about 2 am local time, the sky directly overhead, which will be positioned near the bright star Castor in Gemini (the Twins), will be plowing into the densest part of the debris field. True Geminids will travel away from that part of the sky, but don’t focus on that location as the meteors there will be heading towards you and have very short lengths.

To see the most meteors (during any shower), find a safe, wide-open, dark location, preferably away from the city lights, and just watch the sky with your unaided eyes for a good long while. Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors since their fields of view are too narrow. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen because it’ll ruin your night vision. Keep your eyes to the skies, even while you are chatting with companions. A few years ago, I streamed an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session about meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

The media tend to promote meteor showers on their peak night – but Skylights readers know that showers are worth stepping outside for on the surrounding nights. I’d rather see fewer meteors on a clear night, than none at all on a peak night that’s cloudy! You can’t see meteors in cloudy skies.

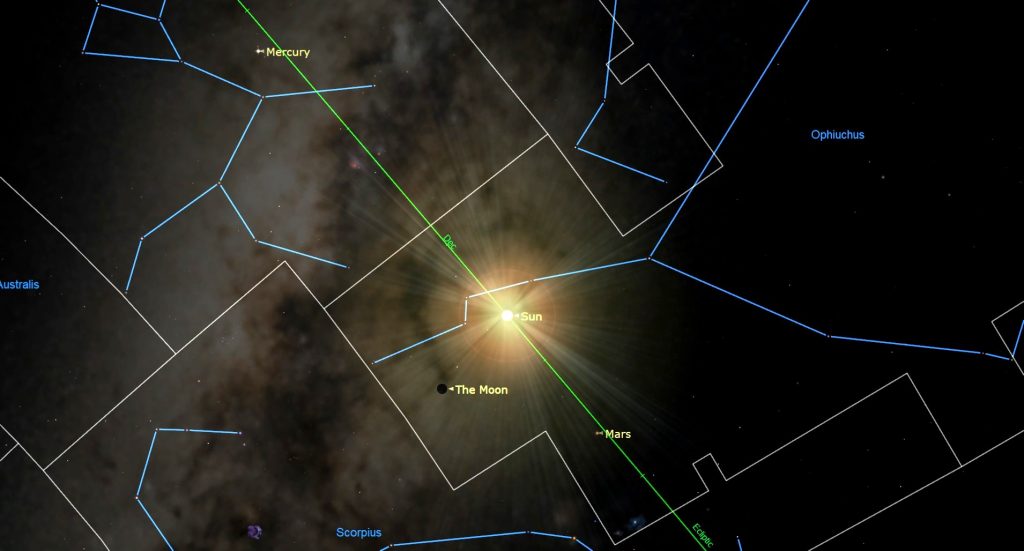

The Moon

The moon will continue to be missing from evening skies worldwide for most of this week while it visits the sun. If your southeastern horizon is cloud-free on Monday morning, you might glimpse the thin crescent of the old moon shortly before sunrise. The moon will formally reach its new moon phase on Tuesday, December 12 at 6:32 pm EST, 3:32 pm PST, or 23:32 Greenwich Mean Time. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), some 4.9° south of the sun.

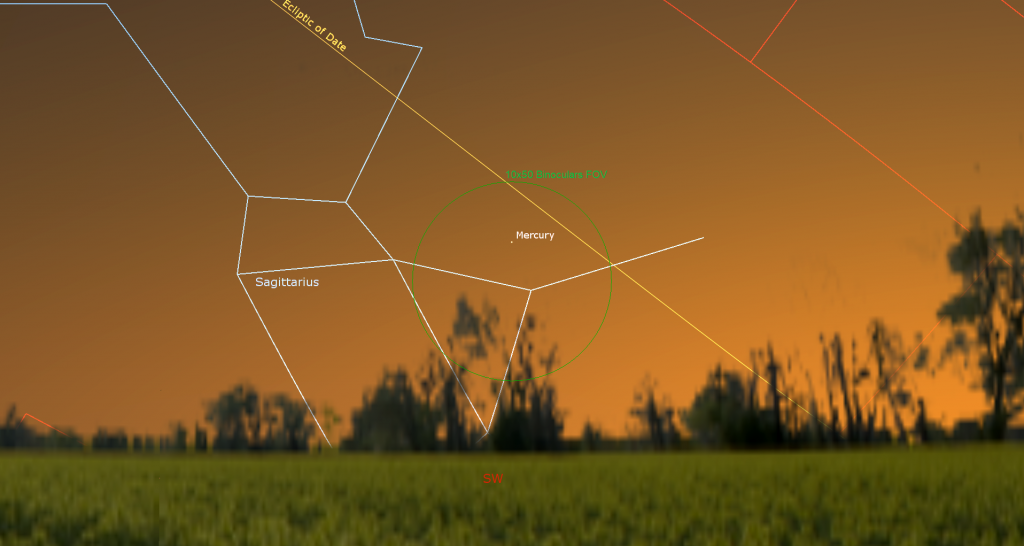

For northerners, the moon will remain hidden until Thursday. On Wednesday observers viewing from the tropics, where the ecliptic and the moon’s orbit will both be vertical at sunset, can see its young crescent shining a palm’s width to the lower left (or 6° to the celestial southwest) of Mercury’s dot right after sunset. Binoculars will aid in the search, but wait until the sun has completely set before turning any optical aids towards the western horizon. Mercury will set at about 5:30 pm local time – the moon about 25 minutes later.

The crescent moon should be a lot easier to see from anywhere on Thursday after sunset, when it will be posing above the western horizon. The waxing crescent moon will linger into the darkening sky on Friday evening, kicking off the best nights of the lunar month for viewing the moon’s terrain while spectacularly lit by slanted sunlight. Use your binoculars or backyard telescope to look for subtle curved wrinkles in Mare Crisium’s grey oval on Friday.

The stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will host the moon on both Friday and Saturday. On next Sunday evening, the moon will among the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Luna’s monthly cruise past the evening planets will commence that night, when the pretty, 29%-illuminated crescent moon will shine only a few finger widths below (or 3° to the celestial south of) Saturn. They’ll be cozy enough to share the field of view in binoculars until they set in the west around 10 pm local time. By then, the moon’s easterly orbital motion and the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift Saturn to the moon’s right.

The Planets

Mercury’s current show after sunset will draw to a close this week. Tonight (Sunday), the planet’s magnitude -0.12 dot will appear more than a palm’s width above the southwestern horizon after the sun has fully set. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a generous crescent phase. The planet will diminish in brightness and descend a little every day, so make your attempt to see it sooner than later. 2024 will bring us better opportunities to see the speedy planet.

After your attempt at Mercury, turn to the southern sky and watch for Saturn’s dot to emerge from the evening twilight. Saturn will be at to its highest point, due south, around 5:15 pm local time (its best telescope viewing time). Then it will sink westward to set around 10:30 pm. By about 6 pm local time, the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will appear to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east) and the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will flicker to Saturn’s lower right (or west). Saturn will remain within the borders of Aquarius until early April, 2025.

Our views of Saturn will gradually become impaired as the planet shifts incrementally sunward each night – so get out there and take a peek! Good binoculars can show that Saturn has rings, and any size, style, or brand of telescope will show them well. From Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° is letting us see the top of its ring plane, and allowing its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn (or celestial west) tonight, then above Saturn on Tuesday-Wednesday, and to a position farther to the left of the planet (or celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

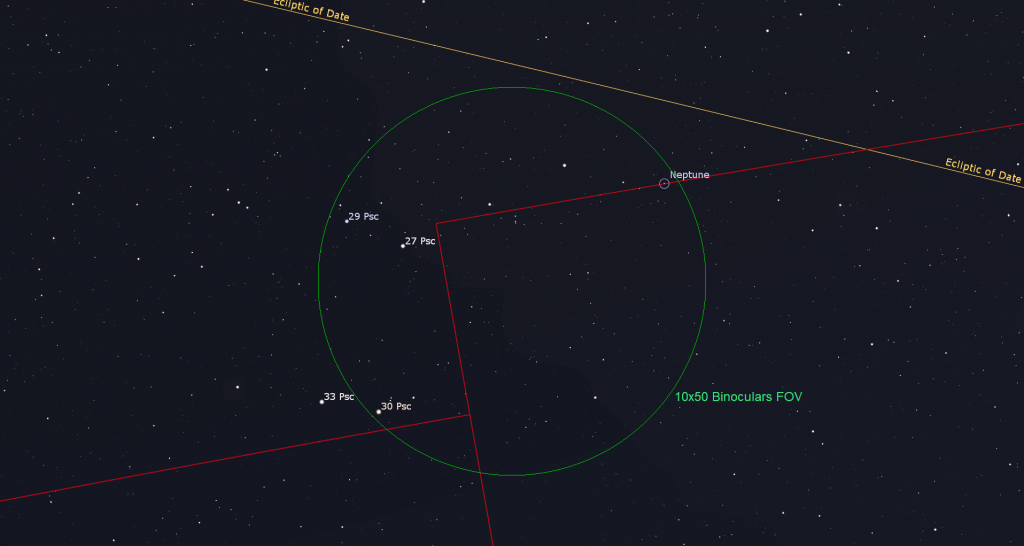

The ice giant planet Neptune, currently 625 times fainter than Saturn, has been following Saturn across the sky every night this year. This week Neptune will be located 2.3 fist diameters to Saturn’s upper left, or 23° to its celestial east-northeast. The diurnal rotation of the sky – the way things tilt as they cross from east to west – will cause Neptune to be lifted increasingly higher than Saturn until Neptune sets at about 12:30 am local time. Take your views of Neptune in early evening, while it’s higher. Neptune is on the border between Aquarius and Pisces (the Fishes). On moonless evenings in December the magnitude 7.9 planet can be observed in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. Position Lambda Piscium and Kappa Piscium, the lowest two stars of the circlet of Pisces, just outside the top of your binoculars’ field of view and look for blue Neptune near the bottom of the field. Or, search less than a binoculars’ field width to the right (or celestial west) of the box formed by the four medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium.

Very bright Jupiter is rising in mid-afternoon now. It will grab your attention in the lower part of the eastern sky even before full dusk each night, and enjoy the view of it almost all night long. Jupiter will climb to a position relatively high in the southern sky around 9:15 pm local time (its peak telescope-viewing time) and then set in the west after 4 am. The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) named Hamal and Sheratan, will shine a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter and the stars forming the Great Square of Pegasus will be higher and to the right.

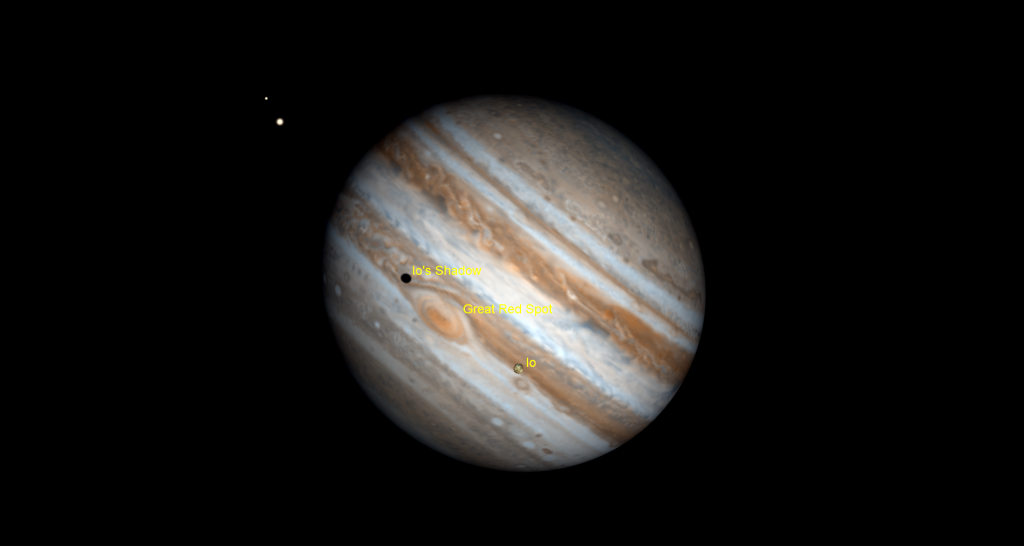

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line flanking the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will be gathered to Jupiter’s right next (Sunday).

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. It’ll appear late on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday night, and also during the wee hours of Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday night, December 12, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 10:32 pm to 12:48 am EST (or 03:32 to 05:48 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again, this time with the Great Red Spot, on Wednesday evening, December 13 from 9:33 to 11:40 pm EST (or 02:33 to 04:40 GMT on December 14). Io’s shadow will cross again on Friday, December 15 from 4:01 to 6:08 pm EST (or 21:01 to 23:08 GMT). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Uranus has been following Jupiter across the night sky, too. During evenings this week, the blue-green planet will be positioned 1.4 fist diameters to Jupiter’s lower left (or 13.9° to the celestial east) in eastern Aries. The bright Pleiades star cluster will also be located a generous fist’s width to Uranus’ left (or 11° to the celestial northeast). At magnitude 5.6, Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes – some people have even been able to spot the planet with their unaided eyes. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus to the same height as Jupiter around 8:30 pm local time and then higher still later on. The planet will set after 5 am local time.

The brilliant planet Venus is gradually sinking sunward and dropping a little lower each morning. It will occupy the southeastern sky before sunrise for another couple of months. If you head out before dawn, you can see the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) shining above our sister planet, particularly her brightest star Spica – but Venus will be descending through Libra (the Scales) this week and next. Viewed through a telescope, our next-door planet will show a shrinking, waxing gibbous disk spanning 15.7 arc-seconds.

Mars has now entered the eastern morning sky, but it won’t become visible with ease for another month.

Watch Algol Fade or Brighten

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most easily observed variable stars for skywatchers. During a ten-hour period that repeats every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes, Algol’s visual brightness dims and re-brightens noticeably when a companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. Astronomers call that arrangement an eclipsing binary star system.

Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to the nearby star Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae). But when fully dimmed, Algol’s brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost identical to Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star that sits just two finger widths to Algol’s lower right (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south). Around 7:34 pm EST on Monday evening, December 11, Algol will commence one of its drops in brightness. At that time it will be shining relatively high in the eastern sky between the very bright star Mirfak and much brighter Jupiter. When Algol reaches its minimum intensity five hours later, at 12:34 am EST on Tuesday morning, it will be located high in the west-northwestern sky. Observers in the time zones flanking Eastern can see this event, too.

Another fine opportunity to watch Algol vary in brightness will arrive on Sunday evening, December 17 in the Americas. At 6:17 pm EST the star will be positioned about halfway up the eastern sky, shining at its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4. Five hours later, at 11:17 pm EST, Algol will be high in the western sky and shining at its full intensity of magnitude 2.1. By then, Almach will be located a generous fist’s diameter below Algol.

Algol’s variations are best seen with unaided eyes or binoculars, which allow you to see its comparison stars at the same time. The website of Sky & Telescope magazine has an interactive tool to let you look up the Minima of Algol where you live. It’s here https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/the-minima-of-algol/.

Appreciating the Pleiades

If you missed last week’s information about the beautiful open star cluster known as the Pleiades and the Seven Sisters in Taurus (the Bull), I posted it here. I also mentioned some highlights of the December evening sky.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!