Peak Venus, a Morning Moon Favours Evening Perseids, Jupiter Parties on Friday Night, and a Look at Aquila!

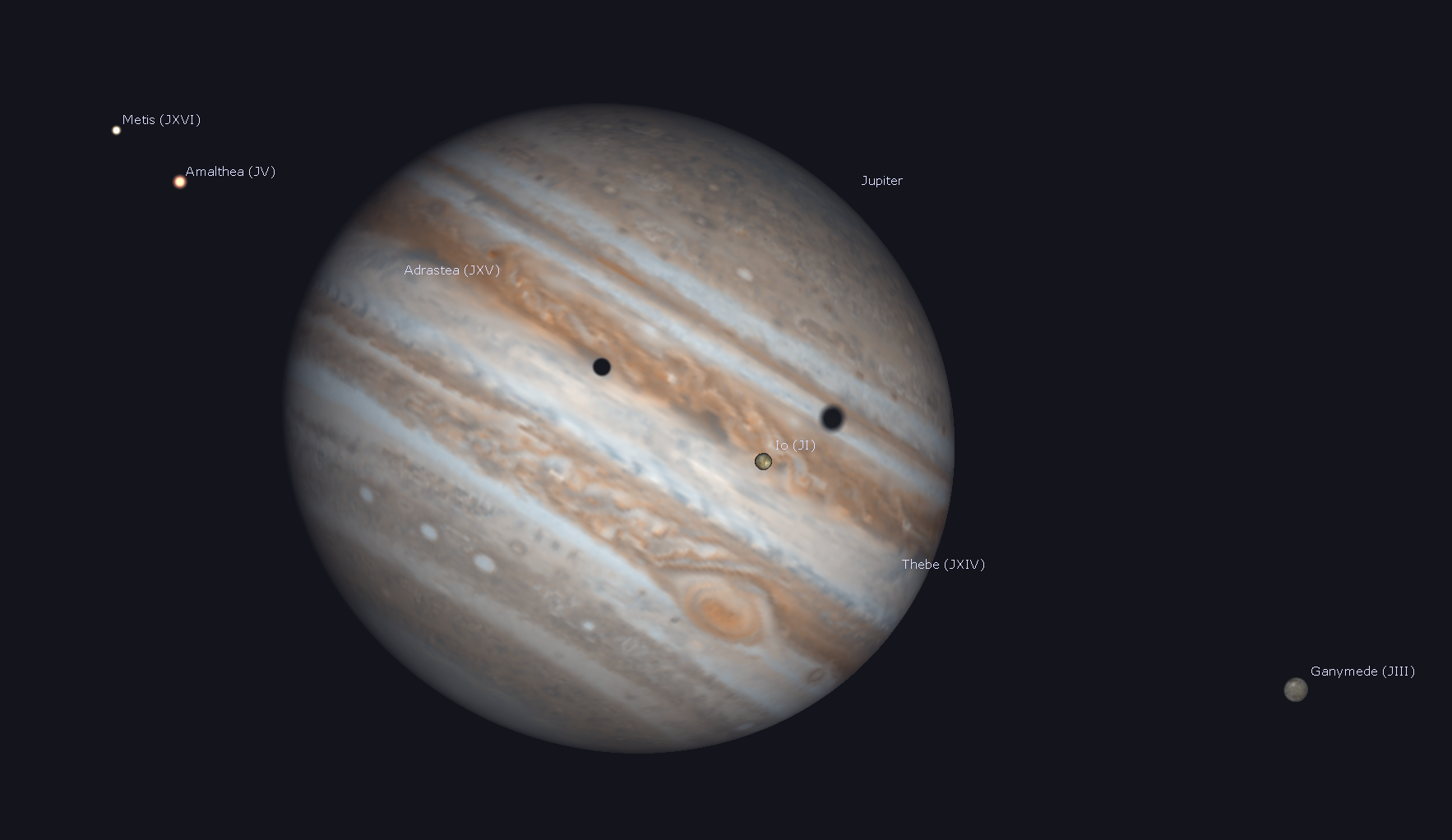

This simulated view of Jupiter shows the double shadow transit, with the Great Red Spot, that will occur on Friday night, August 14. This view is for 1 am EDT on Saturday morning. Ganymede’s shadow is cast by the large moon to the lower right of Jupiter. The event will be observable anywhere in the world where Jupiter is well above the horizon at that time, adjusted to your local time zone.

Hello, August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 9th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

This week, the moon will stay in the post-midnight and morning daytime sky with bright Venus, allowing evening stargazers worldwide to enjoy the sights of Milky Way, constellations near it, like Aquila, and the Perseid Meteor shower. Meanwhile, the bright gas giant planets will shine after dusk, with Mars joining them before midnight – and Jupiter will host a double shadow transit that includes the Great Red Spot. Here are your Skylights!

The Perseids Meteor Shower Peaks!

The prolific Perseids Meteor Shower will reach its peak between dusk on Tuesday night and dawn on Wednesday. On the nights before and after the peak night, the quantity of meteors will be reduced somewhat, but still well worth looking up for! Unfortunately, the last quarter moon will rise after midnight on the peak night this year, so any dimmer pre-dawn meteors will be competing with the moon. Even though many Perseids are extremely bright, I recommend scheduling your viewing time before midnight.

The source of the Perseids material is thought to be a 133-year-period comet named 109P/Swift-Tuttle. The active period for this shower is July 13 through August 26, so keep an eye out for them beyond this week. This shower is known for producing 60-80 meteors per hour at the peak – many manifesting as bright, sputtering fireballs!

Meteor showers are events that re-occur on the same dates every year when the Earth’s orbit carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. (The analogy would be the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!) Over time, the dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into an elongated, tube-shaped cloud in interplanetary space.

When the Earth plows through the cloud, the particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air – producing the long glowing trails we see. The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud – and therefore how long Earth takes to pass through it. The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion, or merely skirt the edges. Not surprisingly, a shower’s performance can vary from year to year.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place in within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of your favourite constellations will look the same as ever at the end of the shower!

While visible anywhere in the night sky, the meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location called the radiant. The Persieds’ radiant sits in northern Perseus, near its border with Camelopardalis (the Giraffe) – so Perseus gives this shower its name. The radiant is low in the northeastern sky during mid-August evenings – and nearly overhead by dawn. Meteor showers are strongest before dawn because that’s the time when the sky overhead is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant constellation is overhead, the entire sky down to the horizon is available for meteors. When it’s low, many of the meteors are hidden below the horizon.

To see the most meteors, try to find a safe viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights (or the moon) behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky is dark. That’s also a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors in that part of the sky will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails.

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use it, turn the brightness down, or cover the screen with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes have will not help you see meteors.

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, caused by the Earth passing through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic Comet 96P/Machholtz, will be tapering off until August 23. Those meteors will appear to travel away from that shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), which sits in low in the southeastern sky during evening. Good luck!

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when the waning moon only shines in the post-midnight sky, and then lingers to shine like a ghost in the morning daytime sky. That means that stargazers around the world will have deliciously dark evening skies all week.

Overnight on Sunday and Monday, the moon will shine among the stars of southern Pisces (the Fishes) and the head of Cetus (the Whale). On Tuesday the moon will reach its last quarter phase, when it is half-illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn sun.

On Thursday morning, shortly after it rises in the east, the moon’s orbital motion will carry it just above the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull). At about 1:25 am EDT, the lit, leading edge of the moon will move in front of (or occult) a medium-bright star named Ain, or Epsilon Tauri, which marks the bull’s higher eye. (The very bright star Aldebaran marks his lower eye.) The star will re-appear, quite abruptly, from behind the moon’s opposite, dark edge at about 2:15 am. You can try to see the star with your unaided eyes – but binoculars or a backyard telescope will be better. Observers across much of eastern North America can see the event, although the exact timing varies by location. Start looking a few minutes before the times indicated above, and remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.

In the eastern sky on Friday morning, the moon’s pretty crescent will shine well above the bright planet Venus. The following morning, the moon will drop to sit just to the upper left (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial north) of Venus. The pair, both sitting among the stars forming the feet of Gemini (the Twins), will fit within the field of view of binoculars, and will make a very nice wide field photograph when composed with some interesting landscape. The moon and Venus will not set until 6 am local time on Saturday. Venus is bright enough to see in the daytime, even with unaided eyes. Taking extreme care to avoid the sun, aim your binoculars at the moon and look for Venus’ bright point of light below it. Then try seeing Venus without them. The moon will end this week as a delicate crescent in central Gemini.

The Planets

This week, two bright early evening planets will be joined by late-rising Mars. As the evening sky darkens after sunset very bright Jupiter will appear first, low in the southeastern sky. Good binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. Even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short) if the air is steady. Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour period of rotation, the GRS appears every second or third night from a given location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk on Monday and Wednesday. It will also appear starting in late evening tonight (Sunday) and Friday, and during the wee hours on Monday and Wednesday.

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. Commencing at 10:30 pm EDT on Friday evening, August 14 (or 02:30 Greenwich Mean Time on Saturday, August 15), observers in the Central Time zone, and east of there, can watch both Ganymede’s large shadow and the Great Red Spot travel across Jupiter’s northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. The show gets even better after midnight when…

… commencing a few minutes after midnight on Friday, and continuing during the wee hours of Saturday, observers in the Americas can witness the rare event of a double shadow transit – accompanied by the Great Red Spot! At 12:06 am EDT (or 04:06 GMT) Io’s small shadow will join Ganymede’s larger shadow and the Great Red Spot already progressing across Jupiter’s northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. The trio will remain visible until Ganymede’s shadow and the GRS move off Jupiter at about 1:53 am EDT (or 05:53 GMT). Io’s shadow will complete its transit at approximately 2:25 am EDT (or 06:25 GMT).

Somewhat dimmer and yellow-tinted, Saturn is chasing brighter, whiter Jupiter across the night sky this summer – lagging it by only a generous palm’s width. By the time both planets become visible to unaided eyes, the stars of eastern Sagittarius (the Archer) will appear, too. That constellation, with its charming teapot-shape, is centred only a fist’s width to the right (or celestial west) of Jupiter. The planets will reach their highest point in the southern sky at about midnight local time this week. So the later you can wait to observe them, the clearer your view of them will be.

Saturn is a spectacular sight in backyard telescopes. Its rings, which will be narrowing every year until the spring of 2025, will span 43 arc-seconds. (That’s about the same as Jupiter’s disk). See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s inner ring from its outer one.

Even a small telescope will show several of Saturn’s brighter moons – especially its largest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we can see the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week in late evening, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to above the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will flip the view around.)

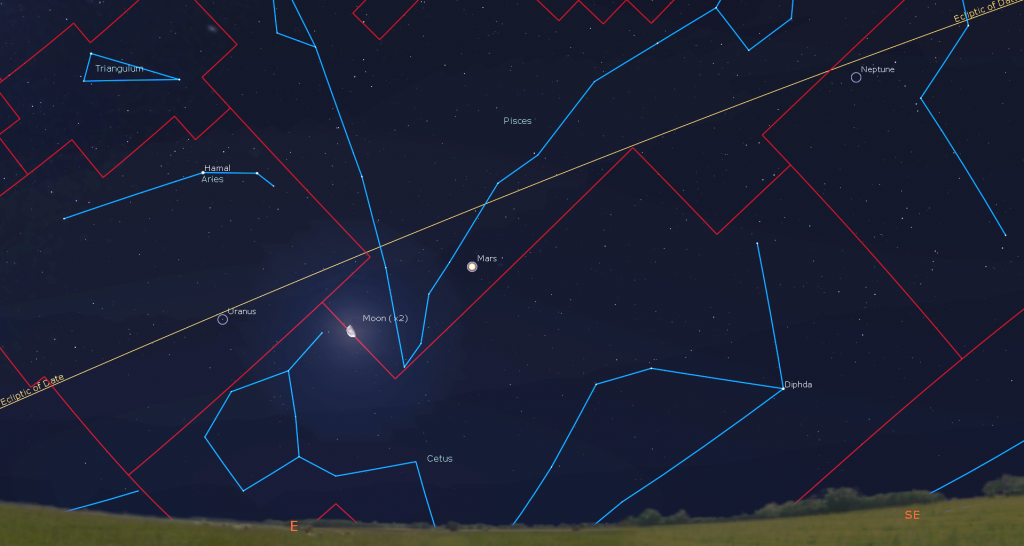

Reddish Mars will put on a great sky show this autumn – but we don’t have to wait until then for good views! Mars is steadily increasing in disk size and brightness because Earth is travelling towards it this summer. This week, the Red Planet will be rising in the east at about 11 pm local time. Mars has been speeding along the ecliptic due to the combined motions of itself and Earth. This week, it will start to cross through the faint, V-shaped constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Mars will be visible as a prominent, reddish dot in the lower part of the sky until dawn, when it will be positioned about five fist diameters above the southern horizon.

Dim and distant Neptune is located about three fist diameters to the right (or 34° to the celestial west) of Mars, among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Neptune rises at about 9:30 pm local time and then climbs higher until about 3 am local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it, almost halfway up the southern sky. Neptune is hard to find without a computerized telescope. The nearest medium-bright star is Hydor, which is located a slim fist’s diameter to the planet’s right. This week’s moonless sky is a good time to search for it.

Blue-green Uranus will rise at about 11:30 pm local time this week. It’s visible with unaided eyes and in binoculars under a dark sky. Look for the magnitude 5.8 ice giant planet sitting in southern Aries (the Ram) – about a fist’s diameter below the ram’s brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. On Saturday, Uranus will cease its normal eastward motion through the distant stars and commence a retrograde loop that will last until January. Retrograde loops happen when the Earth, on the “inside track” around the sun, overtakes a more distant planet.

Early risers can’t miss extremely bright Venus, which will rise in the east at about 2:45 am local time this week, and then remain visible until sunrise as it climbs the sky. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a half-illuminated shape. This week, Venus will be sitting between the bright, orange-tinted star Betelgeuse, in Orion (the Hunter) and the almost-twin stars Castor (higher) and Pollux (lower) in Gemini (the Twins). Venus’ orbital motion is carrying it downward between Orion and Gemini. On Thursday, Venus will reach its greatest separation, 46 degrees west of the sun, for its current morning appearance.

Aquila the Eagle

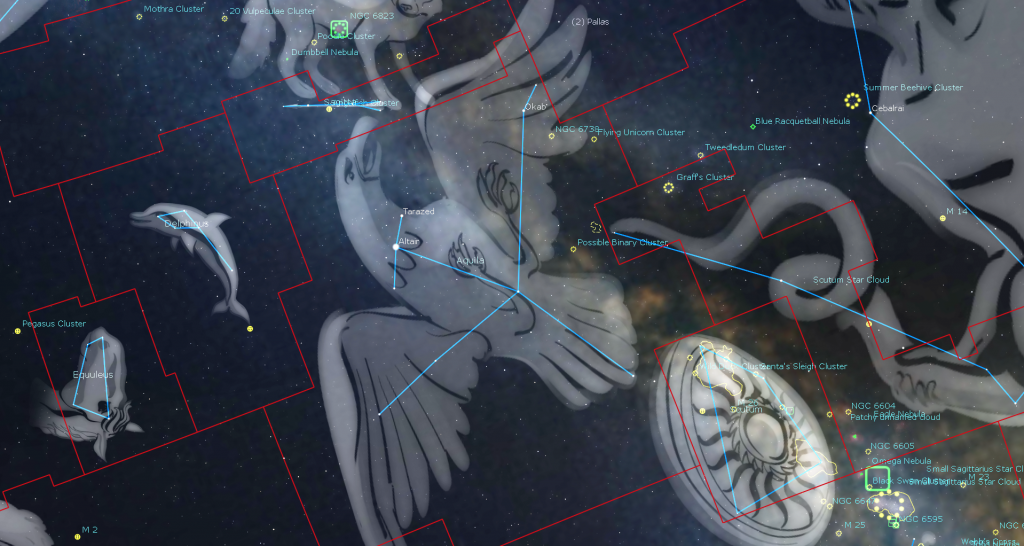

Look halfway up the southeastern sky on early August evenings, and you’ll easily spot the bright, white star Altair, sitting at the bottom corner of the Summer Triangle asterism. Altair is the brightest star in the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) and marks the great bird’s head. The eagle’s body and tail extend downwards to the right, more or less following the Milky Way. The wings extend upwards and downwards.

The great bird straddles the Milky Way, populating it with rich star fields. The celestial equator passes through it – allowing it to be seen easily from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Aquila so clearly resembles a bird that many cultures have seen the same pattern in its stars, including the Babylonians. In Greek mythology, it was the eagle that held Zeus’ thunderbolts. The Romans called it Vultur volans “the flying vulture”. The Hindus associated the stars with the half eagle-half human god Garuda.

Classic Chinese poetry told a well-known story about the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd, one of their four great folktales. In this tale, Zhī Nǚ (織女) the weaver girl was in love with Niú Láng(牛郎) the cowherd. To prevent their forbidden love, they were banished to the heavens, and Zhi Nu, represented by the nearby bright star Vega, and Niu Lan, represented by Altair, were separated by the Silver River, or Milky Way. The two small stars which are visible just above and below Altair, represent their children. In the story, each year on the 7th day of the 7th month in the lunisolar calendar, a flock of magpies would form a bridge, reuniting the lovers for one night only. In some years, the lunisolar calendar begins at the end of January. Some astronomers believe that the magpies are actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

Altair is Arabic for “flying eagle”. The star itself is a yellow-white star about ten times larger than our Sun, and only a mere 17 light-years away, making it the twelfth brightest star in the night sky. At 10 hours, its rotation rate is one of the fastest known, spinning so rapidly that the star has an oblate shape (wider at the equator than it is tall). In the sky, Altair is symmetrically flanked by two small stars named Alshain and Tarazed, or β and γ Aquilae, respectively. Because the three stars resemble a weighing balance, their names are derived from the Arabic phrase for one, “shahin-i tarazu”. The trio spans about three finger widths, or 5° of sky. The lowest star, Tarazed, is interesting. It is a cool, orange giant star located 460 light-years away and shining with almost 3,000 times the luminosity of our Sun; and it emits an abundance of X-rays!

The rest of Aquila’s main stars are dimmer, but nonetheless visible to unaided eyes. Almost a fist’s diameter to the lower right of Altair is the star Delta (δ) Aquilae, representing the body. The wings, each about a fist’s diameter in length, extend up and down from that star. The upper wingtip is marked by the white star Deneb al Okab Australis, also known as Zeta (ζ) Aquilae, and a slightly dimmer star named Deneb al Okab Borealis. Those names mean the southern and northern “tail of the eagle”. (The reference to the tail arose by using a different interpretation of the stars.)

The lower wing is formed by two widely spaced stars. Almizan II is at the elbow, and Almizan III is at the wingtip. (Some apps use the designations Eta and Theta Aquilae.) The eagle’s tail is marked by a pair of small stars a finger’s width apart. The brighter tail star is named Al Thalimain “the two ostriches”. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft, launched in 1973, is coasting towards this star, with an arrival time of about 4 million years!

Sweep your binoculars though the area around and above Aquila to see an abundance of stars from the nearby galactic plane. About a palm’s width to the right of the eagle’s tail, in the next-door constellation Scutum (the Shield), you’ll easily spot another avian object – the Wild Duck Cluster or Messier 11 – a famous bright open cluster.

Within a binoculars’ field of view to the lower right of Okab are two more open star clusters, NGC 6738 and NGC 6709. Another field diameter to their lower right is a bigger, brighter cluster called the Tweedledee Cluster, or the Secret Garden Cluster.

Good “hunting”!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will continue on Tuesday, August 11 from 3:30 to 5 pm EDT. We’ll take a virtual trip to see the skies of the Southern Hemisphere, an update on the Perseids Meteor Shower, and more. Details and the schedule are here. Beyond that, join Jenna and John Reid on alternate Thursdays at 3:30 pm EDT as they run through the RASC’s Explore the Universe certificate.

On Wednesday, August 12 from 6:30 to 8 pm EDT, U of T’s Astronomy & Space Exploration Society (ASX) will present a free online talk entitled How to Measure the Universe’s Oldest Light and What it Tells Us by Dr. Adam Hincks, the inaugural holder of the Sutton Family Chair in Science, Christianity and Cultures at U of T’s David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics. More details are here.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Space Station Flyovers

There are no ISS (or International Space Station) flyovers for the GTA this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!