Pretty Planets Kiss and Dance at Dawn, and Some Dark Sky Delights Til the Librated Cat Comes Back!

The Sword of Orion imaged by John Deans in Bancroft, Ontario on February 2021. This image covers about a thumb’s width of sky, top-to-bottom. The trapezium cluster lies in the heart of the nebula (above centre).

Hello, March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 27th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be out of sight until late this week, and then it will shine prettily after sunset with lonely Uranus and Ceres. Those moonless evenings will be perfect for viewing the sights along the Winter Milky Way. Venus and Mars overlook a conjunction of Saturn and Mercury in the southeast before dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will be out of sight for everyone on Earth from today (Sunday) to Wednesday while it passes the sun at new moon. That event will officially occur on Wednesday at 12:35 pm EST or 17:35 Greenwich Mean Time. While new the moon will be located approximately 5.5 degrees south of the sun in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). That absence will deliver nice and dark night skies for stargazing. (More on that below.)

Our nearest natural neighbour will return to visibility starting on Thursday, and then it will fill with light each night as it increases its angle east of the sun. Thursday’s extremely thin crescent moon will be shining low in the southwestern sky after sunset – bathing in the twilight gloaming. It will be especially pretty around 6 pm local time. The up-down angle of the evening ecliptic in March will rotate the moon’s lit crescent toward the horizon – creating a Cheshire Cat’s smile effect. That whimsical shape will continue for several evenings beyond Thursday. But by then, the moon will be setting later each night in a dark sky, and the “smile” will be widening.

Thursday onward will also be a fine period to watch for Earthshine or the “Ashen Glow”, which is caused when sunlight reflected from Earth’s clouds and the shiny Pacific Ocean slightly illuminates and brightens the part of the moon’s disk that isn’t receiving direct sunlight. Some call this phenomenon “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. The effect will return again after the new moons in April and May.

From Wednesday to Saturday the waxing crescent moon will swim along the crooked boundary dividing Pisces (the Fishes) from Cetus (the Whale), and then end the week next Sunday near Uranus in Aries (the Ram). Those evenings will also be ideal for viewing the terrain along the pole-to-pole lunar terminator in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The sunlight arriving there will be nearly horizontal, casting deep, black shadows to the lunar west of every crater rim, mountain peak, and ridge. New vistas will be highlighted every night! The moon is easy to photograph by holding your phone steadily over a low magnification eyepiece (i.e., one with a larger number labelled on it). If you post a nice picture, tag me!

Due to the moon’s orbital inclination (or tilt) and ellipticity (or out-of-roundness), the moon nods up-and-down by up to 7° and twists left-to-right up by to 8° while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth. Over time, this lunar libration effect lets us see an extra 9% of the moon’s total surface without having to leave the Earth! Lunar features that are normally smeared along the moon’s edge or completely hidden can rotate into clearer view for a few nights. The librated sector of the moon’s limb migrates clockwise around the moon over a lunar month – but librated features can only be observed if their sector happens to be illuminated at the same time.

You can see libration’s effect on the moon at a glance by watching Mare Crisium “the Sea of Crises”. That’s the isolated, dark, round feature located near the right-hand (eastern) edge of the moon, just north of the moon’s equator. Mare Crisium becomes fully illuminated starting about four days after new moon each month. Whenever the waxing crescent moon is descending in the western sky after sunset, Mare Crisium is the most noticeable dark blob within the illuminated crescent.

For anyone interested in viewing elusive libration features, the moon’s northeastern edge will be rotated toward Earth on Friday-Saturday, allowing us to see Mare Humboldtianum, the “Sea of Alexander von Humboldt”, Hubble crater (named for Edwin Hubble), Beals crater (named for Canadian astronomer Carlyle Beals), to name a few features. Binoculars or a backyard telescope will show Mare Humboldtianum as an elongated dark patch close to the crescent’s northern horn-tip (on the right for Northern Hemisphere observers, reversed in the south). A large, dark crater named Endymion will be positioned just inwards from that mare. On the moon’s edge near Mare Crisium, look for the large dark patch of Mare Marginis, the “Edge Sea”.

The Planets

The pre-dawn planet party will continue this week, and for many weeks to come! To enjoy the show, you’ll need clear skies toward the southeast and an unobstructed view in that direction.

Venus will be rising first, at about 4:30 am local time this week. The extremely bright planet will gleam in the lower part of the sky almost until sunrise. Unlike airplanes, Venus won’t move. Long before sunrise, the 250 times fainter dot of reddish Mars will appear below, or 5° to the celestial south, of Venus. Mars will remain visible until the brightening sky hides it, so take your look before about 5:30 am local time. In a telescope Venus will exhibit a 38%-illuminated, waxing crescent phase. Good binoculars will also reveal its shape. Mars will show a tiny disk. (Be sure to turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.)

For the next several weeks, Venus and Mars will be travelling eastward on gradually converging, parallel tracks. At the same time they will be slowly increasing their angle from the sun, and rising earlier. The minor planet designated (4) Vesta will be between them. At magnitude 7.6, Vesta is visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes. On Monday morning, Vesta will be located a thumb’s width above Mars (i.e., celestial northwest). Over the week, slower moving Vesta will shift more and more to the upper right of Venus and Mars as they leave it behind.

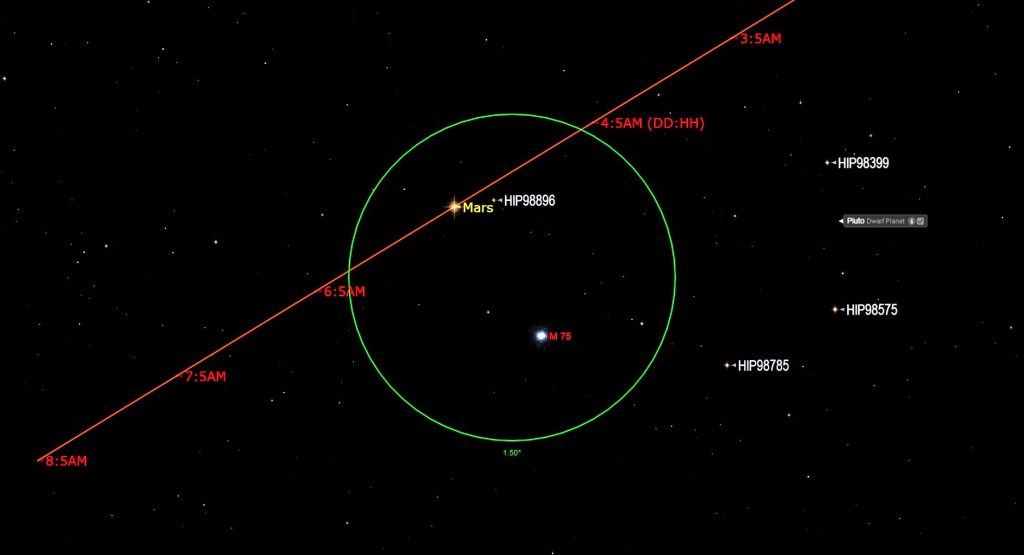

On Saturday, March 5, Mars will pass close to a globular star cluster known as Messier 75 and NGC 6864 in eastern Sagittarius (the Archer). The planet and the cluster will be close enough to one another to share the view in a backyard telescope from Friday to Sunday. At closest approach on Saturday, Mars will sit a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.7 degrees to the celestial north) of the magnitude 9.2 cluster – but your optics may flip and/or invert that arrangement. Observers at southerly latitudes, where Mars will sit higher, will get better views of the event. The dwarf planet Pluto will be located just 1.5 degrees to the west of that cluster, too – but that extremely faint object is beyond the reach of backyard telescopes.

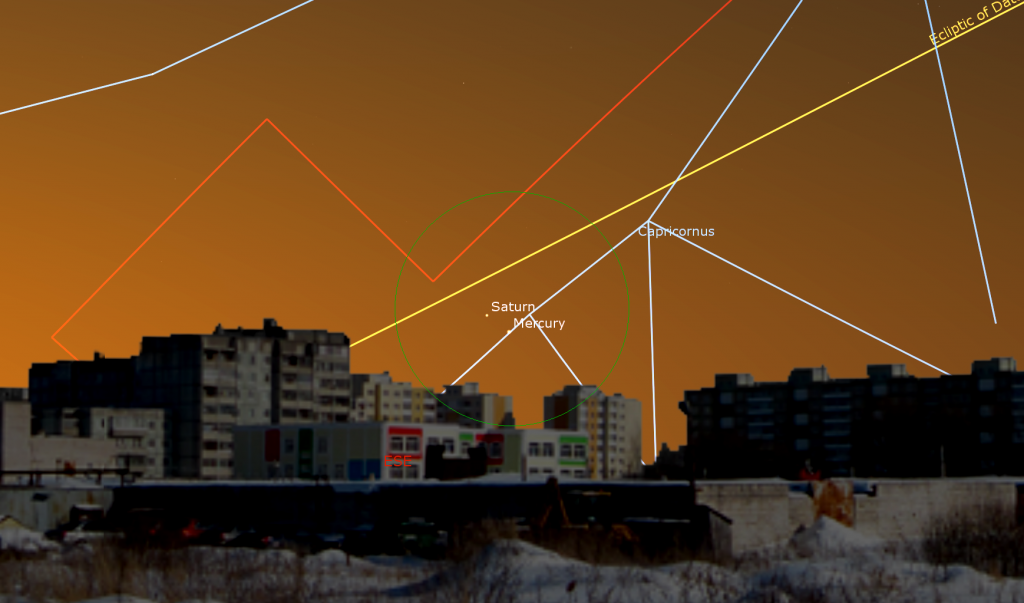

Shortly before 6:30 am in your local time zone, the white dot of Mercury and the yellowish dot of Saturn should rise high enough to become visible. They’ll be two fist diameters to the lower left (or 21° to the celestial east) of Venus and Mars. Mercury and Saturn will be binoculars-close from Monday to Friday, with Mercury approaching Saturn from the upper right (celestial west). At closest approach on Wednesday morning, twice as bright Mercury will sit only a finger’s width to the lower right (or 0.7 degrees to the celestial south) of Saturn – close enough for them to share the view in a backyard telescope. On the following mornings Mercury will shift to Saturn’s lower left. The conjunction will be more easily seen from southerly latitudes, where the planets will shine higher, and in a darker sky. (For eye safety, turn all optical aids away from the eastern horizon before sunrise.)

Uranus is the only planet remaining in the evening sky. Once the sky fully darkens, at around 7:30 pm local time, the magnitude +5.8 planet will be available for viewing in binoculars and backyard telescopes – even with your unaided eyes on dark, clear nights, if you know where to look. The planet’s small, blue-green dot will be positioned a fist’s width to the left of (or 11 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Aries’ brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. In fact, it’s almost exactly midway along a line connecting Hamal with the bright star Menkar in Cetus (the Whale). At 8 pm local time, those stars will sit a third of the way up the west-southwestern sky. By 9 pm local time, Uranus will be too low for decent views.

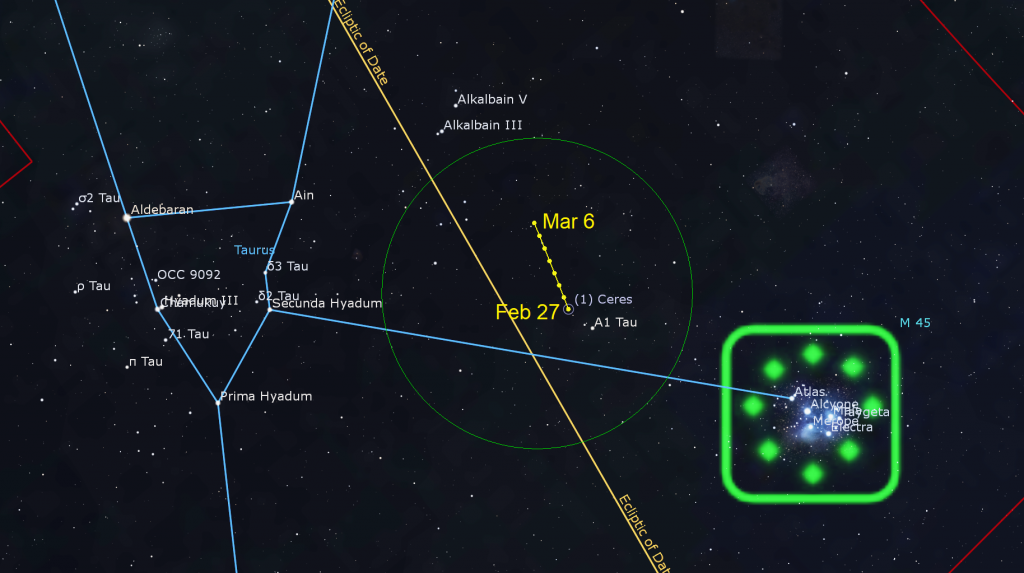

The dwarf planet (formerly largest asteroid) designated (1) Ceres has been passing through Taurus recently – a palm’s width to the upper left (or 5.5° to the celestial southeast) of the Pleiades star cluster. Ceres’ magnitude 8.7 speck is visible in backyard telescopes. Tonight (Sunday) you can look for Ceres just a short distance to the upper left of the medium-bright star named A1 Tauri (or 37 Tauri). Ceres will hop a little father (celestial eastward) from that star on each subsequent night.

Follow the Winter Milky Way

Our solar system sits inside the vast flattened disk of our galaxy, about one-third of the way towards the outer edge. So the faint band of the Milky Way, composed of countless stars in our galactic disk, can be traced in a huge circle around the sky. The core of the galaxy, and therefore most of the stars, is visible on summer nights (and before dawn now) near the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). But the outer rim of the Milky Way sits in the opposite direction – gracing our winter evening skies. Except for a period in late spring when the Milky Way aligns with the horizon, there’s always a part of the galaxy visible in the night sky.

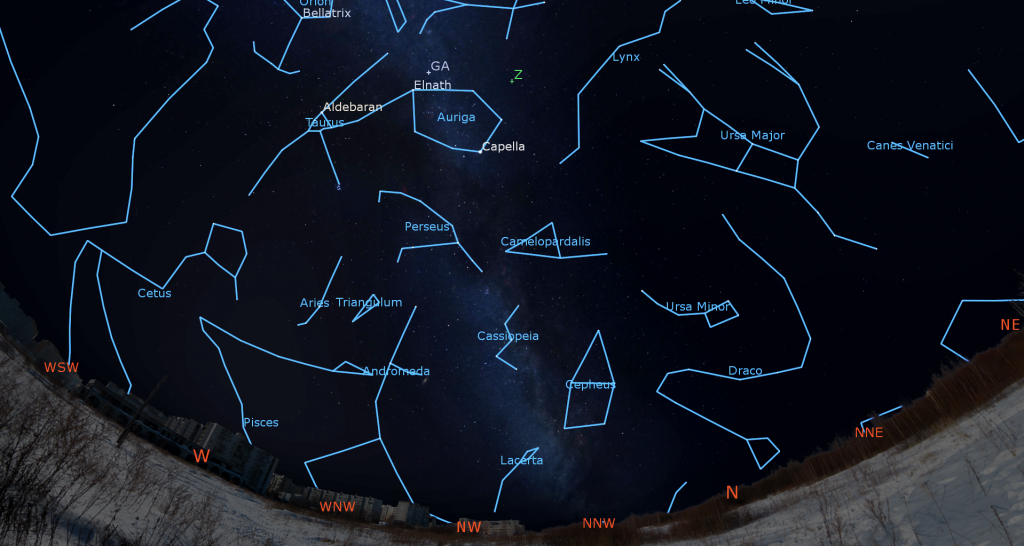

On a clear night, especially this week, when the moon leaves the night sky dark, head outside to an open area away from city lights and look for the outer reaches of the Milky Way. It rises out of the southeastern horizon just to the left (east) of the bright star Sirius in Canis Major (the Big Dog), and gradually diminishes in intensity as you follow it higher, passing between Orion (the Hunter) and Gemini (the Twins), and then just beyond the horn tips of Taurus (the Bull).

The point in the evening sky that sits directly opposite our galaxy’s core is located four finger widths to the left (or 4.3° to the celestial northeast) of a moderately bright star named Alnath (or Elnath), which represents Taurus’ higher horn tip. That star is shared by the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer). In the rough ring of stars that form Auriga, Alnath sits opposite the very bright, yellow star Capella. They are both almost directly overhead at around 7:30 pm local time.

The Milky Way should be visually dimmest near Alnath – but it isn’t. That’s because our galaxy has a non-uniform structure of spiral arms wrapping around its central core, and also because opaque gas and dusk randomly concentrated within the plane of the galaxy blocks starlight. In visible wavelengths, our Milky Way’s dimmest location is actually in the constellations next to Auriga – between Perseus (the Hero) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe).

To finish following the Milky Way across the winter evening sky, turn around and face northwest. In February, Perseus sits high in the northwestern sky, above the distinctive M- or W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). Cassiopeia will be dangling in an up-down orientation. The Milky Way is less intense here, but it strengthens again as we trace its thickening disk downward down through Cassiopeia and then lower, past her husband, Cepheus (the King). If your horizon is low and open, you might catch a glimpse of the bright star Deneb, which marks the tail of Cygnus (the Swan), before it sets. Although much broader there, the Milky Way is darkened by a lot more dust and gas.

Many of the famous Messier List objects sit on or near the Milky Way. That is because they are composed of concentrations of stars (clusters) and gas (nebulae). But looking above and below the plane of the Milky Way (that’s to the left or right of it at this time of year), will reveal other cities of stars – separate galaxies far beyond our own. The brightest and easiest one to see is the great Andromeda Galaxy, also known as Messier 31. It is located only 15° (or 1.5 outstretched fist widths) to the lower left of Cassiopeia’s bottom half.

This week’s dark skies will also be ideal for discovering those clusters and nebulas by scanning the Milky Way with binoculars. Once you find them, pull out the telescope and zoom in on them. Here are some more specific objects to track down.

The portion of Auriga near Capella contains the smaller stars clusters the 4-H Cluster or NGC 1664, NGC 1778, and NGC 1857. The bright Starfish Cluster (or Messier 38 and NGC 1912) and dimmer NGC 1907 near it, plus the bright Pinwheel Cluster (or Messier 36 and NGC 1960) and another cluster named the Letter Y Cluster or NGC 1893 are all located towards the centre of Auriga’s ring of stars. The bright Salt-and-Pepper Cluster (or Messier 37 and NGC 2099) is located just outside the ring and towards the western boundary of Auriga.

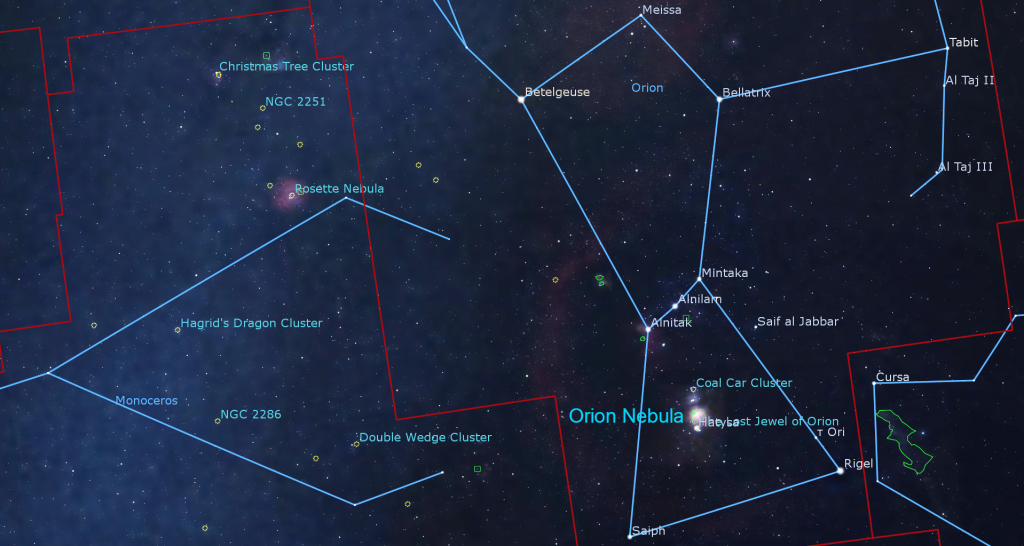

The centre patch of light in Orion’s sword contains the spectacular and bright Orion Nebula (aka Messier 42). Even binoculars will reveal the fuzzy nature of this object. It covers an area of 1.5 by 1 degrees. Messier 43, a section of the same nebula which lies just above (to the north of) M42, has been separated from the main gas cloud by dark foreground dust. A telescope will reveal a complex pattern of veil-like gas and dark dust lanes in those nebulas.

A group of hot, young stars in the core of the Orion Nebula are illuminating the gas in the surrounding cloud. Any telescope at medium magnification will show them as a group of four stars arrayed in a trapezoid shape. This asterism is the Trapezium, also designated as the Theta Orionis cluster. Starting from the bottom (southernmost) star and moving clockwise, they are assigned the letters C (the brightest), D, B, and A. Higher magnification and good seeing should reveal a dimmer E-star sitting between A and B and a fainter F-star tucked close in to the lower left (southeast) of C. The nebula and those stars forming within it are approximately 1,350 light-years from the sun and about 24 light-years across.

The modest constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn) occupies the sky to the left (east) of Orion. Tucked between the very bright stars Procyon and Sirius, this rather dim constellation is often overlooked – but it straddles the winter Milky Way. Among the many treasures to observe within it are the spectacular Rosette Nebula (NGC 2238). Its central star cluster (NGC2244) is easily seen in binoculars. Telescope owners can look for the Christmas Tree Cluster and nebulosity (NGC2264), the Double Wedge Cluster (NGC2232), the tiny, but distinctive Hubble’s Variable Nebula (NGC 2261), and the triple star Beta Monoceros.

Wishing you clear skies!

Walking the Big Dog

If you missed my post about the night sky’s brightest star Sirius and a tour through its home constellation Canis Major (the Big Dog), I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, March 1 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll once again welcome special guests: Isaac Murdock from Serpent River First Nation and Educator Jodie Williams. Together Isaac and Jodie will showcase how Indigenous knowledge systems can enhance current understandings of cosmology and astronomy. Through their new digital resource Lessons From Beyond, we’ll weave together multiple understandings of the universe and show how both Indigenous and Western knowledge systems can reflect, resonate with, and reinforce one another, affirming each other as valid, valuable, and vital. And – we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday evening, March 2 at 7:30 pm EST, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, John Read and I introducing our astronomy book, and an update on the giant Thirty Meter Telescope project. Details are here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!